Abstract

Purpose

To report a patient who developed an unusual combination of central retinal artery occlusion with ophthalmoplegia following spinal surgery in the prone position.

Methods

A 60-year-old man underwent a cervical spinal surgery in the prone position. Soon after recovery he could not open his right eye and had ocular pain due to the general anesthesia. Upon examination, we determined that he had a central retinal artery occlusion with total ophthalmoplegia.

Results

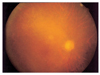

Despite medical treatment, optic atrophy was still present at the following examination. Ptosis and the afferent pupillary defect disappeared and ocular motility was recovered, but visual loss persisted until the last follow-up.

Conclusions

A prolonged prone position during spinal surgery can cause external compression of the eye, causing serious and irreversible injury to the orbital structures. Therefore, if the patient shows postoperative signs of orbital swelling after spinal surgery the condition should be immediately evaluated and treated.

Sudden unilateral or bilateral visual loss occurring after general anesthesia has been reported and attributed to various causes including hemorrhagic shock, blood dyscrasia, hypotension, hypothermia, coagulopathic disorders, direct trauma, embolism, and prolonged compression of the eyes.1,2

However, visual loss with total ophthalmoplegia as a surgical complication has rarely been described as a consequence of prolonged compression of the eye.2-5 There have been no case reports in the literature to date of visual loss following spinal surgery in Korea. We present the first case report of a Korean patient who developed an unusual combination of central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO) with ophthalmoplegia after spinal surgery in the prone position.

A 60-year-old man came to the emergency department of our hospital with an arm tingling sensation in both arms that he had experienced for seven months. Prior to the development of the sensation, he had injuried his neck by a fallen log but reported no pain at the cervical area at the time of presentation at the emergency room. Radiographic views of the cervical spine showed osteophytosis at C4-C5, C5-C6 and at the narrow disc space from C4-C7. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan was performed and revealed a compressed dural sac from C3-C5 with spinal stenosis. The patient had a history of diabetes mellitus but had never received medical treatment for the disease. He was on a diet and his preoperative blood glucose was checked at 285 mg/dL. The patient had no other diseases except diabetes mellitus. His preoperative blood count was normal, but he had a slightly low hemoglobin level at 13.5 mg/dL.

A C3-C5 laminectomy was performed three days after the hospitalization. Under general anesthesia, the patient was put on the operating table in the prone position according to the standard procedure for spinal surgery. During surgery, his neck was kept in a mild flexion position using a head-holter. The total time for the intervention was 295 minutes, and a total of 60 additional minutes was required for the induction and cessation of anesthesia. During the operation, the patient's blood pressure decreased from 120/80 mmHg to 100/60 mmHg for 30 minutes because of some blood loss, and four pints of packed RBCs were transfused. There were no other general problems during surgery. The patient's postoperative hemoglobin concentration was 13.3 mg/dL, which recovered to within normal range the next day.

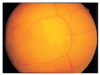

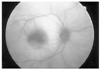

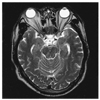

Immediately after recovery from general anesthesia, the patient could not open his right eye because of swelling, and he also had ocular pain in the right eye. He showed visual loss when we examined his right eye on the second postoperative day. He had periorbital swelling, ptosis of the eyelid, chemosis, numbness of the first division of the right trigeminal nerve, afferent pupillary defect, and total ophthalmoplegia. Intraocular pressure was within the normal range. Anterior segments were normal in both eyes. He had a pale optic disc with an edematous retina and fundus examination revealed a cherry-red spot on the fovea (Fig. 1). His fluorescein angiographic examination revealed a delayed arterial filling time (Fig. 2). His brain MRI and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) findings were normal with no evidence of embolic phenomena. However we noted mild swelling of the right periorbital soft tissue and edema of the extraocular muscles in the right eye, sparing their tendons (Fig. 3). Ptosis, the afferent pupillary defect, and ocular movement improved over three postoperative days, but despite medical treatment with carbonic anhydrase inhibitors and corticosteroids, the patient had optic atrophy on the following examination (Fig. 4). Eventually his vision deteriorated until he had no light perception after the last follow up at three months.

Postoperative visual loss following non-ocular surgery is an infrequent but disastrous complication with an estimated incidence ranging from 0.001 to 1% depending on the type of surgery.6,7 A survey of vision loss after spinal surgery has suggested that possible intraoperative causes including patient positioning, blood loss, and intraoperative hypotension could be responsible for this complication. The three recognized causes of postoperative visual loss are ischemic optic neuropathy, central retinal artery or vein occlusion, and cerebral ischemia.8,9

In addition to speculation regarding the intraoperative causes of these problems, several patient risk factors have been suggested. These include chronic hypertension, diabetes mellitus, smoking, vascular disease, and other disorders that result in increased blood viscosity.7,10,11 Because evidence for the role of these risk factors in the pathogenesis of visual loss has been determined from studies in diverse clinical settings, their exact influence on patients who undergo spinal surgery remains unknown.

CRAO is a disease entity that occurs after trauma or embolic, thrombotic, or spasmodic episodes in both children and adults.12 However, postoperative CRAO has rarely been reported as a consequence of direct pressure on the eye during surgery. Slocum et al13 first observed this problem in a patient who underwent a neurosurgical procedure in the prone position using a Bailey headrest. He emphasized that CRAO was caused by the extraocular pressure due to the headrest, or because of anesthetic mask malposition in the presence of hypotension. Givner and Jaffe14 reported four cases of CRAO occurring during abdominal operations in the supine position under mask anesthesia. They suggested that CRAO in these cases was due to a combination of pressure on the eye from the mask under hypotension and prolonged anesthesia. Gillan15 reported two cases in which CRAO developed after general mask anesthesia with vascular hypotension in the supine position. The cause was believed to be similar to that in Givner and Jaffe's report.14 Hollenhorst et al3 put forth the possibility that CRAO followed neurosurgical procedures which took place in the prone position and that used a padded headrest. He reported eight cases of CRAO in his clinical setting that resulted from the inadvertent application of pressure to the orbital contents by the headrest. Bradish and Flowers16 reported the first case of CRAO in the prone position after an orthopedic procedure. They believed that CRAO was due to a combination of hypotensive anesthesia and extrinsic pressure on the inherently susceptible eye of a patient with osteogensis imperfecta.

The mechanism of visual loss after surgery is retinal ischemia secondary to external ocular pressure. The potential causes of this ischemia are venous congestion and arterial occlusion.3,17 Hollenhorst et al3 reproduced visual loss and ophthalmoplegia experimentally in seven rhesus monkeys using orbital compression for 60 minutes in the presence of hypovolemia and hypotension. They proved them by suggesting a mechanism of partial or complete collapse of the arterial and venous channels of the orbit, which were produced by a temponade action of the ocular contents. When the external pressure is released, orbital edema, proptosis, paresis of ocular movement, and massive edema of the retina result from dilation of the ischemic vascular channels and from a transudation of fluid through the permeable walls into the tissue spaces.3 Halfon et al5 suggested that the reversibility of ophthalmoplegia probably depends on the degree of ischemia suffered by both the extraocular muscles and the III, IV, and VI cranial nerves. In our case, postoperative signs of orbital swelling in the affected eye were appreciable evidence of external orbital compression. Our patinet's brain MRI and MRA showed no evidence of cavernous sinus thrombosis and revealed only mild periorbital swelling and enlargement with hyperintensity of the extraocular muscles in the right eye while sparing the tendons. Thus our case is believed to be similar to those reported by Halfon et al.5

CRAO with ophthalmoplegia has been more infrequently reported.2-5 Hollenhorst et al3 noted that the five most severe cases out of eight cases who had proptosis, ptosis, and paralysis of the extraocular muscles improved, even though there was no visual recovery. Halfon et al5 reported two cases of palpebral edema, ocular pain, and total ophthalmoplegia which recovered partial or full ocular motility without the return of vision. Our patient, who exhibited vision loss of the right eye with swelling, ocular pain, and ophthalmoplegia recovered nearly full ocular movement without any improvement of vision, and is therefore believed to be identical to those in the two aforementioned reports.

A prolonged prone position during spinal surgery and excessive pressure on the eye, especially as a result of patient malposition, can cause injury to the orbital structures and can lead to serious ocular complications. Although postoperative vision loss can occur in the absence of globe compression, avoidance of mechanical injury to the globe is very important for the surgeon and anesthetist to be aware of. The surgeon and anesthetist must pay particular attention to avoid the consequences of possible intraoperative movement without adequate eye protection during surgery. Special attention must be given to bradyarrhythmia or other heart conduction illnesses during the operation, as these may be signals of vagal stimulation caused by increased intraorbital pressure.2

We believe this to be the first case report of CRAO with ophthalmoplegia after spinal surgery in the prone position in Korea. If patients show postoperative signs of orbital swelling, especially following surgery in the prone position, the condition must be evaluated and treated immediately. Ophthalmologists must be aware of the possibility of this complication, and always pay attention to avoid this devastating complication.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Ocular fundus photography on the second postoperative day. The right eye shows a pale optic disc with an edematous retina and a cherry-red spot on the fovea.

Fig. 2

Fluorescein angiogram on the second postoperative day. The right eye shows an extreme delay in arterial filling time.

References

1. Brown GC, Magargal LE, Shields JA, et al. Retinal arterial obstruction in children and young adults. Ophthalmology. 1981. 88:18–25.

2. Wolfe SW, Lospinuso MF, Burke SW. Unilateral blindness as a complication of patient positioning for spinal surgery. A case report. Spine. 1992. 17:600–605.

3. Hollenhorst RW, Svien HJ, Benoit CF. Unilateral blindness occurring during anesthesia for neurosurgical operations. Arch Ophthalmol. 1954. 52:819–830.

4. West J, Askin G, Clarke M, Vernon SA. Loss of vision in one eye following scoliosis surgery. Br J Ophthalmol. 1990. 74:243–244.

5. Halfon MJ, Bonardo P, Valiensi S, et al. Central retinal artery occlusion and ophthalmoplegia following spinal surgery. Br J Ophthalmol. 2004. 88:1350–1352.

6. Warner ME, Warner MA, Garrity JA, et al. The frequency of perioperative vision loss. Anesth Analg. 2001. 93:1417–1421.

7. Williams EL, Hart WM Jr, Tempelhoff R. Postoperative ischemic optic neuropathy. Anesth Analg. 1995. 80:1018–1029.

8. Myers MA, Hamilton SR, Bogosian AJ, et al. Visual loss as a complication of spine surgery. A review of 37 cases. Spine. 1997. 22:1325–1329.

9. Stevens WR, Glazer PA, Kelley SD, et al. Ophthalmic complications after spinal surgery. Spine. 1997. 12:1319–1324.

10. Brown RH, Schauble JF, Miller NR. Anemia and hypotension as contributors to perioperative loss of vision. Anesthesiology. 1994. 80:222–226.

11. Katz DM, Trobe JD, Cornblath WT, Kline LB. Ischemic optic neuropathy after lumbar spine surgery. Arch Ophthalmol. 1994. 112:925–931.

12. Grossman W, Ward WT. Central retinal artery occlusion after scoliosis surgery with a horseshoe headrest. Case report and literature review. Spine. 1993. 18:1226–1228.

13. Slocum HC, O'Neal KC, Allen CR. Neurovascular complications from malposition on the operating table. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1948. 86:729–734.

14. Givner I, Jaffe N. Occlusion of the central retinal artery following anesthesia. Arch Ophthalmol. 1950. 43:197–201.

15. Gillan JG. Two cases of unilateral blindness following anaesthesia with vascular hypotension. Can Med Assoc J. 1953. 69:294–296.

16. Bradish CF, Flowers M. Central retinal artery occlusion in association with osteogenesis imperfecta. Spine. 1987. 12:193–194.

17. Walkup HE, Murphy JD. Retinal ischemia with unilateral blindness-a complication occurring during pulmonary resection in the prone position; report of two cases. J Thorac Surg. 1952. 23:174–175.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download