Abstract

Purpose

We describe the occurrence of a massive retinal hemorrhage following anterior chamber paracentesis in uveitic glaucoma.

Methods

A 33-year-old man who suffered from uveitic glaucoma was transferred to our hospital. The IOP in both his eyes was documented to vary between 11 mmHg and 43 mmHg and remained at a continuously high level for 7 months despite maximally tolerable medical treatment. A paracentesis was performed bilaterally to lower the IOP.

Results

Immediately after the paracentesis, massive retinal hemorrhages occurred in the left eye. Multiple round blot retinal hemorrhages with white centers occurred in the equator and peripheral retina, and small slit hemorrhages were observed in the peripapillary area. A fluorescence angiography(FAG) showed no obstruction of retinal vessels but a slightly delayed arteriovenous time in the left eye.

Paracentesis is frequently performed in patients who have an intolerably high intraocular pressure (IOP) despite medical treatment. There have been several cases of decompression retinopathy after filtering surgery1-3 for uveitic glaucoma, juvenile glaucoma, neovascular glaucoma, angle closure glaucoma, steroid induced glaucoma and primary open angle glaucoma. However, decompression retinopathy has not been reported following paracentesis in uveitic glaucoma. There has been one reported case of multiple retinal hemorrhages caused by macular branch artery occlusion following paracentesis.1 This report describes a patient with uveitic glaucoma who showed evidence of multiple retinal hemorrhages immediately following paracentesis.

A 33-year-old man who had been suffering from decreased visual acuity for 2 years presented for treatment. His history included chronic idiopathic anterior and posterior uveitis in both eyes. On initial examination, visual acuity with correction (-2.75Dsph/-3.75Dsph) was 0.16/0.1 (OD/OS) and the IOP was 17/13 mmHg. Keratoprecipitates and Grade 4 inflammatory cells were presented in the anterior chamber of both eyes. Snowbank-like accumulations of debris, cotton wool spots, and exudates were noted in the inferior nasal vitreous area of the left eye, and vitreous floaters were noted in the right eye. He had a wide-open filtering angle except for scattered mild peripheral anterior synechiae, and no rubeosis was presented in either eye. No abnormalities were observed on systemic work up and he did not take any medication that could have caused the bleeding.

Initial treatment involved a subtenon triamcinolone acetonide injection and topical steroid to reduce the inflammation in both eyes. Since the inflammation did not subside, after 7 days intravitreal injection of triamcinolone acetonide (IVTA, 4 mg) was administered to both eyes. This reduced the inflammation for 2 weeks. In the month following IVTA, the IOP gradually began to increase. An intravenous osmotic solution, acetazolamide, and eye solutions were used to control the IOP, which returned to 19-27 mmHg in both eyes. After 5 months, anterior and posterior inflammation increased again and IVTA was repeated in both eyes. During the course of the medical treatment, anterior and posterior inflammation improved.

Two months later the IOP began to increase again. IOP was documented to vary between 11 mmHg and 43 mmHg and was near the maximum for 7 months. Visual acuity with correction was 0.16/0.16 (OD/OS). Since the high intraocular pressure (36 mmHg OD, 41 mmHg OS) persisted despite maximal tolerated medical therapy, we performed an anterior chamber paracentesis with a 30G needle to decrease the IOP in both eyes. No deformation of the globe occurred during the procedure and the intraocular pressure immediately dropped to 5 mmHg in both eyes.

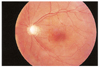

A day later, a fundoscopy and fluorescence angiography (FAG) revealed multiple peripapillary and peripheral preretinal and deep retinal hemorrhages in the left eye (Fig. 1A). No hemorrhages were present in the right eye. FAG showed multiple areas of blocked fluorescence in the central and peripheral retina of the left eye. However, there was no obstruction in the retinal vessels and only a delayed arteriovenous phase (17 sec) (Fig. 1B). Visual acuity with correction was 0.16/0.16 (OD/OS) and IOP was 15/17 mmHg. Two months later, the massive retinal hemorrhage had completely resolved (Fig. 2). Visual acuity with correction was 0.16/0.16 (OD/OS) and IOP was 33/32 mmHg. Several months later, an Ahmed valve was implanted in both eyes.

A variety of causes have been proposed for retinal hemorrhage following rapid reduction of IOP.1 It is possible that inherited or acquired vascular abnormalities in the eye may result in increased capillary fragility. However, in the present case, no vascular abnormalities were found on any of the examinations prior to the procedure, and there was no history of easy bruising or bleeding that would indicate systemic vascular fragility. The patient was not known to take aspirin or any other medications that could promote bleeding.

Normal IOP maintains the normal corneal-scleral curvature. Acute hypotony may cause structural changes to the eye tissues, and the effects vary depending on the duration of the hypotony. During hypotony, scleral collapse and deformity can occur. The inferior oblique muscle inserts into the submacular area and causes horizontal folding of the choroid.4 It is possible that the transient mechanical and structural deformity associated with a sudden decrease in IOP in an already ischemic retina could result in capillary fragility.1 No such deformation of the globe occurred during paracentesis in our patient.

Fechtner et el. propose that a rapid reduction of IOP may decrease the resistance to blood flow, and the resulting increase in flow may stress the capillaries, resulting in multiple focal endothelial leaks.2,5 Healthy retinal blood vessels are capable of efficient autoregulation.5-7 Defects in this autoregulation have been reported in patients with glaucoma and may contribute to the development of retinal hemorrhage.7,8 It is possible that retinal autoregulation was affected in our patient, who had an unusually high IOP for 7 months. The sudden reduction in IOP following paracentesis may have caused a correspondingly large increase in arterial perfusion pressure in the retina. This, in turn, may have overwhelmed the autoregulatory capacity of the retinal vasculature, resulting in multiple focal hemorrhages.5,9 It should be noted that the duration and extent of the elevated IOP was similar in both eyes, and it is not clear why retinal hemorrhage did not occur in the right eye.

In a relatively young patient with a large complement of axons, sudden lowering of intraocular pressure could induce forward shifting of the lamina cribrosa and acute blockage of axonal transport.6,10 The abrupt packing of intra-axonal materials into the disc tissue may also indirectly compress the central retinal vein and precipitate hemorrhagic retinopathy resembling central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO).3,10 A FAG of our patient showed no obstruction of retinal vessels but only a delayed arteriovenous phase time (17 sec). The pattern of the retinal hemorrhage involved multiple small slit shaped hemorrhages in the peripapillary area and round blot-like hemorrhages with white centers in the midperipheral area. The young age, delayed AV time, and presence of peripapillary slit shaped hemorrhages indicate that indirect compression of the central retinal vein due to the rapid IOP reduction might have contributed to the pathogenesis in our patient.

In the present study, the patient had a relatively high IOP for about 7 months, compared with previous reports in which the IOP elevation period was typically several days to a few months.2,8,11 An extended period of elevated IOP may contribute to a defect in autoregulation, which may in turn be associated with the development of decompression retinopathy.

The visual prognosis in decompression retinopathy varies from case to case.1-3,11 Specifically, in cases of retinal hemorrhage involving the fovea or CRVO, very poor visual results were achieved despite complete resolution of the retinal hemorrhage.3,11 Recovery of preoperative visual acuity after the resolution of retinal hemorrhage has been reported in cases of retinal hemorrhage involving the posterior pole, excluding the fovea, peripheral, or peripapillary retina.2,11 In our patient there was no change in visual acuity in the left eye the day after development of the retinal hemorrhage.

Paracentesis is a very useful method that promptly reduces pressure in patients with elevated IOP that persists despite medical treatment. However, it is important to be aware that patients who have a longterm, relatively high IOP have a greater risk of developing decompression retinopathy following paracentesis and filtering surgery. It may, therefore, be beneficial to limit the use of paracentesis before surgery in patients with a high IOP. It may also be beneficial to perform paracentesis in several smaller stages to reduce the risk of adverse responses to a sudden decrease in IOP.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

(A) This is a photograph of the fundus in the left eye after the first paracentesis. Scatter blot hemorrhages in the peripapillary and peripheral multiple preretinal and deep retinal hemorrhages can be seen. Visual acuity with correction was 0.16 and IOP 17 mmHg (OS). (B) Fluorescein angiography of the left eye after the first paracentesis. Multiple, blocked fluorescence due to the retinal hemorrhages and vascular filling appears delayed at 17 sec.

References

1. Gupta R, Browning AC, Amoaku WM. Multiple retinal haemorrhages (decompression retinopathy) following paracentesis for macular branch artery occlusion. Eye. 2005. 19:592–593.

2. Fechtner RD, Minckler D, Weinreb RN, et al. Complications of glaucoma surgery: ocular decompressive retinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1992. 110:965–968.

3. Suzuki R, Nakayama M, Satoh N. Tree types of retinal bleeding as a complication of hypotony after trabeculectomy. Ophthalmologica. 1999. 213:135–138.

4. Schubert HD. Postsurgical hypotony: relationship to fistulization, inflammation, chorioretinal lesion, and the vitreous. Sur Ophthalmol. 1996. 41:97–125.

5. Geijer C, Bill A. Effects of raised intraocular pressure on retinal, prelaminar, laminar, and retrolaminar optic nerve blood flow in monkeys. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1979. 18:1030–1042.

6. Sossi N, Anderson DR. Effect of elevated intraocular pressure on blood flow: Occurrence in the cat optic nerve head studied with iodoantipyrine I 125. Arch Ophthalmol. 1983. 101:98–101.

7. Grunwald JE, Riva CE, Stone RA, et al. Retinal autoregulation in open-angle glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 1984. 91:1690–1694.

8. Nah G, Aung T, Yip CC. Ocular decompression retinopathy after resolution of acute primary angle closure glaucoma. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2000. 28:319–320.

9. Givens K, Shields MD. Suprachoroidal hemorrhages after glaucoma filtering surgery. Am J Ophthalmol. 1987. 103:689–694.

10. Minckler DS, Bunt AH. Axoplasmic transport in ocular hypotony and papilledema in the monkey. Arch Ophthalmol. 1977. 95:1430–1436.

11. Dudley DF, Leen MM, Kinyoun JL, et al. Retinal hemorrhages associated with ocular decompression after glaucoma surgery. Ophthalmic Surg Laser. 1996. 27:147–150.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download