1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association Publishing;2013.

2. Faraone SV, Biederman J, Mick E. The age-dependent decline of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analysis of follow-up studies. Psychol Med. 2006; 36:159–165.

3. Kessler RC, Adler LA, Gruber MJ, Sarawate CA, Spencer T, Van Brunt DL. Validity of the World Health Organization Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS) screener in a representative sample of health plan members. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2007; 16:52–65.

4. Mannuzza S, Klein RG, Bessler A, Malloy P, LaPadula M. Adult outcome of hyperactive boys. Educational achievement, occupational rank, and psychiatric status. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993; 50:565–576.

5. Barkley RA, Fischer M, Edelbrock CS, Smallish L. The adolescent outcome of hyperactive children diagnosed by research criteria: I. An 8-year prospective follow-up study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1990; 29:546–557.

6. Biederman J, Faraone S, Milberger S, Curtis S, Chen L, Marrs A, Ouellette C, Moore P, Spencer T. Predictors of persistence and remission of ADHD into adolescence: results from a four-year prospective follow-up study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996; 35:343–351.

7. Claude D, Firestone P. The development of ADHD boys: a 12-year follow-up. Can J Behav Sci. 1995; 27:226–249.

8. Bernfort L, Nordfeldt S, Persson J. ADHD from a socio-economic perspective. Acta Paediatr. 2008; 97:239–245.

9. Mannuzza S, Klein RG. Long-term prognosis in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2000; 9:711–726.

10. Barkley RA, Fischer M, Smallish L, Fletcher K. Young adult outcome of hyperactive children: adaptive functioning in major life activities. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006; 45:192–202.

11. Gau SS, Chen SJ, Chou WJ, Cheng H, Tang CS, Chang HL, Tzang RF, Wu YY, Huang YF, Chou MC, et al. National survey of adherence, efficacy, and side effects of methylphenidate in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in Taiwan. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008; 69:131–140.

12. Atzori P, Usala T, Carucci S, Danjou F, Zuddas A. Predictive factors for persistent use and compliance of immediate-release methylphenidate: a 36-month naturalistic study. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2009; 19:673–681.

13. Rothenberger A, Becker A, Breuer D, Döpfner M. An observational study of once-daily modified-release methylphenidate in ADHD: quality of life, satisfaction with treatment and adherence. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011; 20:Suppl 2. S257–65.

14. Yang J, Yoon BM, Lee MS, Joe SH, Jung IK, Kim SH. Adherence with electronic monitoring and symptoms in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatry Investig. 2012; 9:263–268.

15. Winterstein AG, Gerhard T, Shuster J, Zito J, Johnson M, Liu H, Saidi A. Utilization of pharmacologic treatment in youths with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in Medicaid database. Ann Pharmacother. 2008; 42:24–31.

16. Wong IC, Asherson P, Bilbow A, Clifford S, Coghill D, DeSoysa R, Hollis C, McCarthy S, Murray M, Planner C, et al. Cessation of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder drugs in the young (CADDY)--a pharmacoepidemiological and qualitative study. Health Technol Assess. 2009; 13:iii–iiv. ix–xi. 1–120.

17. Garbe E, Mikolajczyk RT, Banaschewski T, Petermann U, Petermann F, Kraut AA, Langner I. Drug treatment patterns of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents in Germany: results from a large population-based cohort study. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2012; 22:452–458.

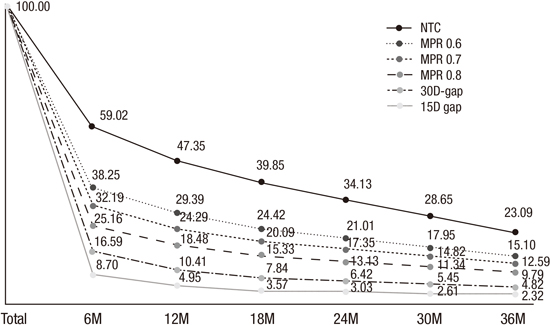

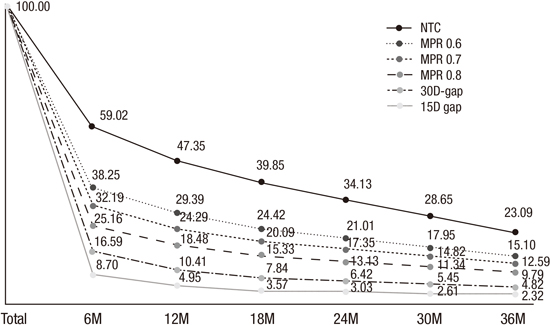

18. Hong M, Lee WH, Moon DS, Lee SM, Chung US, Bahn GH. 36 month naturalistic retrospective study of clinic-treated youth with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2014; 24:341–346.

19. Lawson KA, Johnsrud M, Hodgkins P, Sasané R, Crismon ML. Utilization patterns of stimulants in ADHD in the Medicaid population: a retrospective analysis of data from the Texas Medicaid program. Clin Ther. 2012; 34:944–956.e4.

20. Hong M, Kwack YS, Joung YS, Lee SI, Kim B, Sohn SH, Chung US, Yang J, Bhang SY, Hwang JW, et al. Nationwide rate of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder diagnosis and pharmacotherapy in Korea in 2008-2011. Asia-Pac Psychiatry. 2014; 6:379–385.

21. Wolraich ML, Hannah JN, Baumgaertel A, Feurer ID. Examination of DSM-IV criteria for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in a county-wide sample. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1998; 19:162–168.

22. Angold A, Erkanli A, Egger HL, Costello EJ. Stimulant treatment for children: a community perspective. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000; 39:975–984.

23. Yoshimasu K, Barbaresi WJ, Colligan RC, Voigt RG, Killian JM, Weaver AL, Katusic SK. Childhood ADHD is strongly associated with a broad range of psychiatric disorders during adolescence: a population-based birth cohort study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2012; 53:1036–1043.

24. Steiner JF, Prochazka AV. The assessment of refill compliance using pharmacy records: methods, validity, and applications. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997; 50:105–116.

25. Peterson AM, Nau DP, Cramer JA, Benner J, Gwadry-Sridhar F, Nichol M. A checklist for medication compliance and persistence studies using retrospective databases. Value Health. 2007; 10:3–12.

26. Barner JC, Khoza S, Oladapo A. ADHD medication use, adherence, persistence and cost among Texas Medicaid children. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011; 27:Suppl 2. 13–22.

27. Cramer JA, Roy A, Burrell A, Fairchild CJ, Fuldeore MJ, Ollendorf DA, Wong PK. Medication compliance and persistence: terminology and definitions. Value Health. 2008; 11:44–47.

28. Hodgkins P, Sasané R, Meijer WM. Pharmacologic treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children: incidence, prevalence, and treatment patterns in the Netherlands. Clin Ther. 2011; 33:188–203.

29. Kim YJ, Oh SY, Lee J, Moon SJ, Lee WH, Bahn GH. Factors affecting adherence to pharmacotherapy in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: a retrospective study. J Korean Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010; 21:174–181.

30. Smith E, Koerting J, Latter S, Knowles MM, McCann DC, Thompson M, Sonuga-Barke EJ. Overcoming barriers to effective early parenting interventions for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): parent and practitioner views. Child Care Health Dev. 2015; 41:93–102.