This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

To determine whether rapid HIV tests in public health centers might encourage voluntary HIV testing, a pilot project was conducted in four selected public health centers in Seoul, 2014. During the period April 10 to November 28 of pilot project, 3,356 rapid tests were performed, and 38 were confirmed as positive. The monthly average numbers of voluntary HIV tests and HIV-positive cases were up to nine-fold and six-fold larger, respectively, than those of the period before application of the rapid HIV test. Among 2,051 examinees that completed questionnaires, 90.3% were satisfied. In conclusion, the use of rapid HIV tests in public health centers promoted voluntary HIV testing and was satisfactory for examinees.

Keywords: HIV, Rapid HIV Test, Anonymous HIV Test, Public Health Center, Seoul Metropolitan City

The number of newly diagnosed HIV cases has been declining worldwide (

1). In Korea, however, that number is increasing constantly (

2), and the proportion of late-presentation diagnoses has risen steadily (

3). Early diagnosis and treatment of HIV infection are important for both patients and public health, because they can reduce morbidities and mortalities (

4) and HIV transmission (

5). To increase the early detection of HIV, voluntary testing should be encouraged (

6); however, according to Korean national HIV surveillance data, only 13% of the cumulative reported cases of HIV infection in Korea were diagnosed by voluntary testing as of 2013 (

2).

To encourage voluntary HIV testing, there have been many attempts to introduce the rapid HIV test in healthcare and outreach settings (

78910111213). These studies reported that use of the rapid HIV test could promote HIV screening, and the majority of individuals receiving the rapid HIV test preferred it because they can be notified results on the spot. For these reasons, a pilot project was conducted in Seoul to determine if the use of the rapid HIV test in public health centers could increase the frequency of voluntary HIV testing in Korea.

Anonymous voluntary rapid HIV testing was conducted at four public health centers in Seoul by the Seoul Metropolitan Government from April 10 to November 28, 2014. We adopted the SD BIOLINE HIV-1/2 3.0 (Standard Diagnostics, Inc., Yongin-si, Korea) rapid test kit as an alternative to the conventional anonymous EIA test. Examinees were offered the rapid test by finger-stick. All examinees were provided with a brochure and booklet describing the details of negative and reactive results and the process of the rapid test in the public health centers.

Examinees were notified of the results of the rapid test by phone or in person in the laboratory 20 minutes after blood sampling. Examinees with reactive results in the rapid tests were provided with detailed guidance on the meaning of the reactive result and the following procedures.

Reactive results were confirmed by Western blot. The Western blot tests were performed at the Seoul Research Institute of Public Health and Environment or the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which is the standard for HIV infection confirmation in Korea. The examinee confirmed the Western blot results within 1 week by telephone. Examinees confirmed for HIV infection by Western blot were referred to staff in charge of HIV/AIDS management at the public health centers for post-test counseling. All staff members of the four pilot project sites followed protocol standard operation procedures during the study period.

To determine whether the use of the rapid HIV test in public health centers might encourage voluntary HIV testing, we compared the average monthly frequencies of anonymous HIV testing during a pilot project in 2014 with those of the previous year at the same four pilot project sites. To determine the acceptability of the rapid HIV tests in public health centers, we asked the examinees to complete short questionnaires that included age, sex, residential district, travel time required to take the rapid test, degree of satisfaction with the rapid test, and the reason for requesting the rapid test. Data on the reason for requesting the rapid test, residential district, and travel time for the rapid test were collected only from July 2014, because those three questions were added at that time. This study protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of Seoul National University (IRB No. 1501-102-640). Verbal informed consent was obtained from all participants.

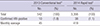

During the pilot project, 3,356 rapid HIV tests were performed, and 38 were confirmed positive by Western blot. In 2013 when the rapid test was not available and only the conventional EIA test was performed, 542 voluntary HIV tests were performed and 10 cases were confirmed positive at the four public health centers (

Table 1). After adoption of the rapid HIV test, the average monthly numbers of HIV tests performed and HIV-positive cases confirmed were approximately nine-fold and six-fold larger, respectively, than those in the previous year. Among 3,356 examinees, 83 had reactive results from the rapid test, of whom 62 accepted the confirmatory test (i.e., Western blot), and 21 refused. Of the 62 who accepted the confirmatory tests, all were notified of the final results. Finally, 38 were confirmed to have HIV infection, and two were indeterminate (

Fig. 1). The positive predictive value of the rapid HIV test was 61.3%.

Sixty-one percent of the 3,356 examinees who underwent rapid tests completed voluntary short questionnaires. Among 2,051 examinees who responded, 85.4% were men, and 74.3% were young adults aged 16-34 years; 62.7% were very satisfied and 27.6% satisfied with the rapid test. Among 1,247 examinees who answered the question about their home location, 26% were living outside Seoul, and their median travel time required to take the rapid test was 60-110 minutes. Concerning the reason for requesting the rapid tests, 96.2% of responders replied that it was because they could get the test results in 20 minutes, while a few (2.6%) answered that it was because no venipuncture was done.

There are several challenges to implementing the rapid HIV test in public health centers. First, sufficient information regarding the potential of the rapid HIV test to provide false positive and false negative results should be provided to examinees (

13). The EIA test is more reliable screening method, especially in initial period of infection (

14151617). For this reason, examinees were informed that a result of HIV tests might be negative if they recently infected, and they should be tested again in three months by staff members of the four pilot test sites. Second, the results of the rapid tests vary depending on the skill of the examiner, such that there may be user error or site-specific error (

18), thus, staffs for offering rapid HIV test should be trained how to offer rapid HIV testing and discuss testing results (

19).

However, as we described above, adoption of the rapid test could encourage voluntary HIV testing and was satisfactory for examinees, which would be beneficial both to HIV patients themselves and for public health concerns. Considering the worsening HIV epidemic in Korea, the advantages of the rapid test are much greater than the disadvantages.

In conclusion, the use of the rapid HIV test in public health centers could encourage voluntary HIV test and was satisfactory for examinees. Thus, we propose wide adoption of the rapid HIV test.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download