1. Kwon S. Thirty years of national health insurance in South Korea: lessons for achieving universal health care coverage. Health Policy Plan. 2009; 24:63–71.

2. Choi YJ, Ko BS, Cho KH, Lee JH. Concept, values, current status and prospect of primary care in Korea. J Korean Med Assoc. 2013; 56:856–865.

3. Lee JY, Jo MW, Yoo WS, Kim HJ, Eun SJ. Evidence of a broken healthcare delivery system in Korea: unnecessary hospital outpatient utilization among patients with a single chronic disease without complications. J Korean Med Sci. 2014; 29:1590–1596.

4. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. OECD Reviews of Health Care Systems: Korea. Paris: OECD Publications Service;2003.

5. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. OECD Reviews of Health Care Quality: Korea - Raising Standards. Paris: OECD Publications Service;2012.

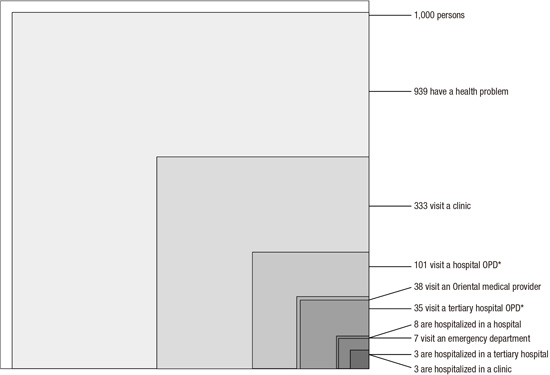

6. White KL, Williams TF, Greenberg BG. The ecology of medical care. N Engl J Med. 1961; 265:885–892.

7. Horder J, Horder E. Illness in general practice. Practitioner. 1954; 173:177–187.

8. Green LA, Fryer GE Jr, Yawn BP, Lanier D, Dovey SM. The ecology of medical care revisited. N Engl J Med. 2001; 344:2021–2025.

9. Thacker SB, Greene SB, Salber EJ. Hospitalizations in a southern rural community: an application of the ‘ecology model’. Int J Epidemiol. 1977; 6:55–63.

10. Dovey S, Weitzman M, Fryer G, Green L, Yawn B, Lanier D, Phillips R. The ecology of medical care for children in the United States. Pediatrics. 2003; 111:1024–1029.

11. Fryer GE Jr, Green LA, Dovey SM, Yawn BP, Phillips RL, Lanier D. Variation in the ecology of medical care. Ann Fam Med. 2003; 1:81–89.

12. Bliss EB, Meyers DS, Phillips RL Jr, Fryer GE Jr, Dovey SM, Green LA. Variation in participation in health care settings associated with race and ethnicity. J Gen Intern Med. 2004; 19:931–936.

13. Fukui T, Rhaman M, Takahashi O, Saito M, Shimbo T, Endo H, Misao H, Fukuhara S, Hinohara S. The ecology of medical care in Japan. Japan Med Assoc J. 2005; 48:163–167.

14. Leung GM, Wong IO, Chan WS, Choi S, Lo SV; Health Care Financing Study Group. The ecology of health care in Hong Kong. Soc Sci Med. 2005; 61:577–590.

15. Yawn BP, Fryer GE, Phillips RL, Dovey SM, Lanier D, Green LA. Using the ecology model to describe the impact of asthma on patterns of health care. BMC Pulm Med. 2005; 5:7.

16. Chou LF. The ecology of mental health care in Taiwan. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2006; 33:492–498.

17. Ferro A, Kristiansson PM. Ecology of medical care in a publicly funded health care system: a registry study in Sweden. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2011; 29:187–192.

18. Shao CC, Chang CP, Chou LF, Chen TJ, Hwang SJ. The ecology of medical care in Taiwan. J Chin Med Assoc. 2011; 74:408–412.

19. Tokunaga S, Sameshima H, Ikenoue T. Applying the ecology model to perinatal medicine: from a regional population-based study. J Pregnancy. 2011; 2011:587390.

20. Hansen AH, Halvorsen PA, Forde OH. The ecology of medical care in Norway: wide use of general practitioners may not necessarily keep patients out of hospitals. J Public Health Res. 2012; 1:177–183.

21. Ishida Y, Ohde S, Takahashi O, Deshpande GA, Shimbo T, Hinohara S, Fukui T. Factors affecting health care utilization for children in Japan. Pediatrics. 2012; 129:e113–9.

22. Roncoletta A, Gusso GD, Bensenor IM, Lotufo PA. A reappraisal in São Paulo, Brazil (2008) of “The Ecology of Medical Care:” the “One Per Thousand’s Rule”. Fam Med. 2012; 44:247–251.

23. Shao S, Zhao F, Wang J, Feng L, Lu X, Du J, Yan Y, Wang C, Fu Y, Wu J, et al. The ecology of medical care in Beijing. PLoS One. 2013; 8:e82446.

24. Chang CP, Chou CL, Chou YC, Shao CC, Su HI, Chen TJ, Chou LF, Yu HC. The ecology of gynecological care for women. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014; 11:7669–7677.

25. Duwe EA, Petterson S, Gibbons C, Bazemore A. Ecology of health care: the need to address low utilization in American Indians/Alaska Natives. Am Fam Physician. 2014; 89:217–218.

26. Vo TL, Duchesnes C, Vögeli O, Belche JL, Massart V, Giet D. The ecology of health care in a Belgian area. Acta Clin Belg. 2015; 70:280–286.

27. Johansen ME, Kircher SM, Huerta TR. Reexamining the ecology of medical care. N Engl J Med. 2016; 374:495–496.

28. Jeong YH, Ko SJ, Son CK, Lee JH, Lee YG, Seo NK, Tae YH, Kim YS. A Report on the Procedure of Korea Health Panel Survey. Seoul: Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs; National Health Insurance Corporation;2008.

29. Cho JJ, Kwon YJ, Jung SH. Community based health care service design on chronic disease for enhancing primary care and the status of community based primary care project. Korean J Fam Pract. 2015; 5:173–178.

30. Statistics Korea. Korean Statistical Information Service [Internet]. accessed on 18 March 2016. Available at

http://kosis.kr.

31. Kim K, Lee S, Park H. Reforming medical education for strengthening primary care. J Korean Med Assoc. 2013; 56:891–898.

32. Kim YI, Hong JY, Kim K, Goh E, Sung NJ. Primary care research in South Korea: its importance and enhancing strategies for enhancement. J Korean Med Assoc. 2013; 56:899–907.

33. Armstrong D. Outline of Sociology as Applied to Medicine. 5th ed. London: Arnold Publication;2003.

34. Fry J, Moulds A, Strube G, Gambrill E. The Family Good Health Guide: Common Sense on Common Health Problems. Lancaster: MTP Press Limited;1982.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download