This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

Prompt malaria diagnosis is crucial so antimalarial drugs and supportive care can then be rapidly initiated. A 15-year-old boy who had traveled to Africa (South Africa, Kenya, and Nigeria between January 3 and 25, 2011) presented with fever persisting over 5 days, headache, diarrhea, and dysuria, approximately 17 days after his return from the journey. Urinalysis showed pyuria and hematuria. Blood examination showed hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and hyperbilirubinemia. Plasmapheresis and hemodialysis were performed for 19 hospital days. Falciparum malaria was then confirmed by peripheral blood smear, and antimalarial medications were initiated. The patient’s condition and laboratory results were quickly normalized. We report a case of severe acute renal failure associated with delayed diagnosis of falciparum malaria, and primary use of supportive treatment rather than antimalarial medicine. The present case suggests that early diagnosis and treatment is important because untreated tropical malaria can be associated with severe acute renal failure and fatality. Physicians must be alert for correct diagnosis and proper management of imported tropical malaria when patients have travel history of endemic areas.

Keywords: Plasmodium falciparum, Malaria, Diagnosis, Renal Failure, Dialysis, Plasmapheresis

INTRODUCTION

Malaria causes illness and death in both adults and children, and is prevalent in tropical regions such as South and Southeast Asia, South and Central America, and Africa (

1). According to the 2014 malaria report by the World Health Organization, 198 million malaria cases occurred globally, a 30% decrease in the malaria incidence and 47% decrease in associated mortality rates since 2000 (

2). Malaria is caused by parasites of the genus

Plasmodium, namely,

P. falciparum,

P. vivax,

P. malariae,

P. ovale, and

P. knowlesi.

P. falciparum induces severe malaria with life threatening complications like cerebral malaria, acute kidney injury, severe anemia, acidosis, jaundice, and acute respiratory distress syndrome (

34).

In Korea, the incidence of malaria infection and transmission has been decreasing since the initiation of a national malaria eradication program. However, the incidence of imported malaria (traveler malaria) is increasing steadily (

5). Most patients have been infected with

P. vivax, 74.8% of which comes from Asia, and

P. falciparum, 86.2% of which reportedly originates from Africa (

5).

Malaria can be diagnosed soon after symptom onset using a peripheral blood smear, and several reports have detailed symptoms and comorbid conditions of patients receiving antimalarial treatment (

567). We present a case of a 15-year-old boy with

P. falciparum malaria, in whom diagnosis and treatment with antimalarial drugs was delayed. Although it was a slow recovery, the combination of plasmapheresis and renal replacement therapy were helpful before the antimalarial drugs to bring the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) to within almost 50% of the normal value.

CASE DESCRIPTION

A previously healthy 15-year-old boy presented to our hospital on February 21, 2011 with persistent fever for 5 days, abdominal pain, diarrhea, headache, dual flank pain, dysuria, and oliguria. The patient noted that a high fever (39.0-41.5℃) and severe headache began approximately 17 days after his return from Africa (South Africa, Kenya, and Nigeria on January 3-25, 2011). He had experienced diarrhea in Africa and also upon his return. He did not take antimalarial prophylaxis in Africa. He reported no consumption of special food and no history of medication.

Vital signs were as follows: temperature of 38.7℃, heart rate of 96 beats/min, blood pressure of 100/60 mmHg, and respiration rate of 30 breaths/min. The patient appeared acutely ill with anemic conjunctiva and icteric sclera. His abdomen was soft and distended with palpable hepatosplenomegaly and dual flank tenderness. The neurological examination was normal except for the reported headache. Laboratory results were as follows: complete blood count revealed a white blood cell (WBC) count of 2.50 × 103/μL with segmented neutrophils (63%), hemoglobin of 11.2 g/dL, and a platelet count of 2.7 × 104/μL. Urinalysis showed microscopic hematuria (blood 3+), pyuria (WBC > 30/high power field), and protein (+) in the urine. Hepatorenal impairment was present with an aspartate aminotransferase level of 152 IU/L, alanine aminotransferase level of 53 IU/L, total bilirubin (T-bili) of 9.23 mg/dL, direct bilirubin (D-bili) of 5.22 mg/dL, blood urea nitrogen (BUN) of 40 mg/dL, and creatinine of 2.96 mg/dL. Additional laboratory tests revealed a decreased complement C3 of 45.7 mg/dL (normal range: 90-180 mg/dL) and C4 of 8.7 mg/dL (normal range: 10-40 mg/dL). A peripheral blood smear examination was negative for Plasmodium parasites. Tests for hepatitis markers (types A, B, and C) were negative.

Although we suspected malarial infection, tests were negative for malaria. We considered a diagnosis of hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) due to thrombocytopenia, hematuria, diarrhea, and kidney failure. We admitted the patient to the intensive care unit, but after 3 days his fever persisted and his headache had worsened. Oliguria and symptoms of acute kidney injury (pulmonary edema and serum potassium elevation) were increased. Laboratory examination revealed increased hyperbilirubinemia (T-bili of 15.49 mg/dL and D-bili of 9.54 mg/dL), BUN of 77 mg/dL, creatinine of 6.17 mg/dL, and a decreased GFR of 20 mL/min/1.73 m

2. Blood and urine cultures, a Shiga-toxin/enterohemorrhagic

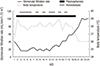

Escherichia coli test, and Widal and Coombs tests were negative. We could not exclude thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. The indicated treatment was simultaneous hemodialysis and plasmapheresis. One daily cycle of plasmapheresis was the main therapy and intermittent hemodialysis was an adjuvant therapy after an initial 4 consecutive days of hemodialysis. Once hemodialysis was started, kidney function slowly improved. On day 17, after 10 hemodialysis sessions, the GFR returned to the level noted on admission day. Peripheral blood smears performed on the day of admission (

Fig. 1A) and after 10 days (

Fig. 1B) were reported to be negative for malaria. However, the blood smear was found to be positive on 10 days by retrospective review, resulting in late diagnosis by wrong interpretation of the blood smear. On day 19 (

Fig. 1C), a peripheral blood smear yielded a diagnosis of malaria. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) confirmed

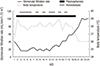

P. falciparum infection. Treatment with the antimalarial drug mefloquine was initiated. The patient’s fever subsided and the GFR increased faster without plasmapheresis and hemodialysis (

Fig. 2). The GFR normalized within 4 days of initiating the antimalarial drug. He was discharged on day 31, and the laboratory results were in normal range as follows: T-bilirubin of 0.39, D-bilirubin of 0.19, BUN of 15 mg/dL, and creatinine of 0.81 mg/dL. A complete blood count on day 31 revealed a hemoglobin of 13.1 g/dL and a platelet count of 1.77 × 10

5/μL. Vital signs were stable and the patient did not report any symptoms. He was discharged with no medication and followed for 3 years in our outpatient clinic with no subsequent health problems.

| Fig. 1Peripheral blood smears. (A) On admission day. (B) On 10 hospital day. (C) On 19 hospital day. Arrows indicate RBCs with a ring.

|

| Fig. 2Clinical progression of fever, and glomerular filtration rate in the reported patient.

|

DISCUSSION

The present patient exhibited negative smear tests for malaria on admission to our hospital one month after his trip to Africa, but had life-threatening disease progression with severely decreased renal function (

8). Delayed diagnosis and treatment of malaria could result in serious complications and poor prognosis (

9101112). Following a study about imported malaria in the Republic of Korea, 2003-2012, the Korean Center for Disease Control and Prevention reported that the time interval between the first clinical visit and diagnosis of imported malaria was 3 days (

5). Although peripheral blood smears (thin and thick) are the gold standard for diagnosing malaria (

12), in our case, only the peripheral blood smear on day 19 after the patient’s admission allowed a positive diagnosis of malaria. We suspected malaria throughout, but had negative results from the first two tests. Later, we confirmed the positive result of the third peripheral blood smear with a PCR test. After confirming malaria, retrospective review of the patient’s 3 peripheral blood smears revealed that the second test was positive for

Plasmodium ring form trophozoites and schizonts (1-2 trophozoites or schizonts/high power field). One paper reported that malaria diagnosis is initially missed in 59% of cases (

6), therefore history taking is important. If malaria is strongly suspected, but a smear test is negative, the smear test should be repeated together with PCR. False negative reading of the smears may occur according to small parasite numbers in the blood or cycles of the parasite. However, the present case was misdiagnosed by missing the rings at the initial reading because malaria is a rare disease in our hospital.

Novel diagnostic techniques with high sensitivity and specificity, such as PCR, loop-mediated isothermal amplification, mass spectrometry, and flow cytometry, have recently been introduced (

11). In severe and complicated malaria cases, patients require proper supportive therapy as well as the antimalarial medication, including intensive care as soon as possible. Mortality from severe malaria can be as high as 75% when diagnosis and treatment are delayed (

12). Supportive therapy is considered based on disease severity and can include ventilator care in cases of respiratory failure, renal replacement therapy, fluid replacement, and avoidance of nephrotoxic drugs in cases of acute kidney injury (

413). Renal replacement therapy and plasmapheresis are considered new techniques with advantages in treating malaria (

4). In our case, antimalarial drugs were not immediately initiated due to delayed diagnosis. Although it was a slow recovery, the combination of plasmapheresis and renal replacement therapy were helpful without antimalarial drugs to bring the GFR to almost 50% of the normal value. Once antimalarial drugs were initiated, the patient’s fever subsided and he quickly recovered from acute renal failure. This result shows the importance of supportive care in cases of delayed malaria diagnosis, but also highlights the importance of prompt malaria diagnosis and initiation of antimalarial drugs.

In conclusion, history taking, particularly about travel, the travel area, and its endemic diseases are crucial for diagnosing imported diseases. If malaria is suspected, it is important to repeat the examinations and use more sensitive and specific tests in order to diagnose malaria earlier. Antimalarial drugs are definite for treating malaria, but if antimalarial drugs cannot be immediately initiated, proper supportive care such as plasmapheresis and renal replacement therapy is important, particularly when a patient’s condition is deteriorating by renal failure. Korean physicians may meet malaria patients in a very rare occasion as the present case but should consider its correct and early diagnosis when the patient has travel history to endemic areas.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download