1. Bul M, Zhu X, Rannikko A, Staerman F, Valdagni R, Pickles T, Bangma CH, Roobol MJ. Radical prostatectomy for low-risk prostate cancer following initial active surveillance: results from a prospective observational study. Eur Urol. 2012; 62:195–200.

2. Hayes JH, Ollendorf DA, Pearson SD, Barry MJ, Kantoff PW, Stewart ST, Bhatnagar V, Sweeney CJ, Stahl JE, McMahon PM. Active surveillance compared with initial treatment for men with low-risk prostate cancer: a decision analysis. JAMA. 2010; 304:2373–2380.

3. Reese AC, Landis P, Han M, Epstein JI, Carter HB. Expanded criteria to identify men eligible for active surveillance of low risk prostate cancer at Johns Hopkins: a preliminary analysis. J Urol. 2013; 190:2033–2038.

4. Cooperberg MR, Carroll PR, Klotz L. Active surveillance for prostate cancer: progress and promise. J Clin Oncol. 2011; 29:3669–3676.

5. Tosoian JJ, JohnBull E, Trock BJ, Landis P, Epstein JI, Partin AW, Walsh PC, Carter HB. Pathological outcomes in men with low risk and very low risk prostate cancer: implications on the practice of active surveillance. J Urol. 2013; 190:1218–1222.

6. Ha YS, Yu J, Salmasi AH, Patel N, Parihar J, Singer EA, Kim JH, Kwon TG, Kim WJ, Kim IY. Prostate-specific antigen density toward a better cutoff to identify better candidates for active surveillance. Urology. 2014; 84:365–371.

7. Kryvenko ON, Carter HB, Trock BJ, Epstein JI. Biopsy criteria for determining appropriateness for active surveillance in the modern era. Urology. 2014; 83:869–874.

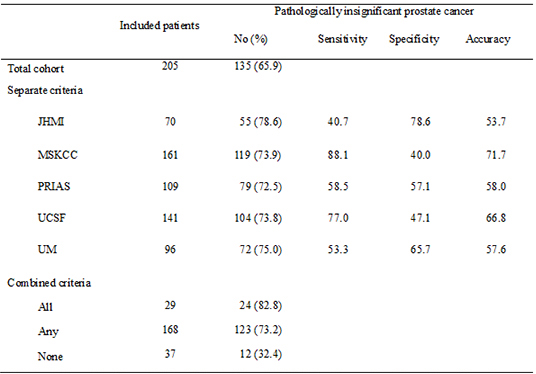

8. Iremashvili V, Pelaez L, Manoharan M, Jorda M, Rosenberg DL, Soloway MS. Pathologic prostate cancer characteristics in patients eligible for active surveillance: a head-to-head comparison of contemporary protocols. Eur Urol. 2012; 62:462–468.

9. Dall'Era MA, Albertsen PC, Bangma C, Carroll PR, Carter HB, Cooperberg MR, Freedland SJ, Klotz LH, Parker C, Soloway MS. Active surveillance for prostate cancer: a systematic review of the literature. Eur Urol. 2012; 62:976–983.

10. van den Bergh RC, Ahmed HU, Bangma CH, Cooperberg MR, Villers A, Parker CC. Novel tools to improve patient selection and monitoring on active surveillance for low-risk prostate cancer: a systematic review. Eur Urol. 2014; 65:1023–1031.

11. Lee DH, Jung HB, Lee SH, Rha KH, Choi YD, Hong SJ, Yang SC, Chung BH. Comparison of pathological outcomes of active surveillance candidates who underwent radical prostatectomy using contemporary protocols at a high-volume Korean center. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2012; 42:1079–1085.

12. Tosoian JJ, Trock BJ, Landis P, Feng Z, Epstein JI, Partin AW, Walsh PC, Carter HB. Active surveillance program for prostate cancer: an update of the Johns Hopkins experience. J Clin Oncol. 2011; 29:2185–2190.

13. Adamy A, Yee DS, Matsushita K, Maschino A, Cronin A, Vickers A, Guillonneau B, Scardino PT, Eastham JA. Role of prostate specific antigen and immediate confirmatory biopsy in predicting progression during active surveillance for low risk prostate cancer. J Urol. 2011; 185:477–482.

14. Bul M, Zhu X, Valdagni R, Pickles T, Kakehi Y, Rannikko A, Bjartell A, van der Schoot DK, Cornel EB, Conti GN, et al. Active surveillance for low-risk prostate cancer worldwide: the PRIAS study. Eur Urol. 2013; 63:597–603.

15. Dall'Era MA, Konety BR, Cowan JE, Shinohara K, Stauf F, Cooperberg MR, Meng MV, Kane CJ, Perez N, Master VA, et al. Active surveillance for the management of prostate cancer in a contemporary cohort. Cancer. 2008; 112:2664–2670.

16. Soloway MS, Soloway CT, Eldefrawy A, Acosta K, Kava B, Manoharan M. Careful selection and close monitoring of low-risk prostate cancer patients on active surveillance minimizes the need for treatment. Eur Urol. 2010; 58:831–835.

17. Beauval JB, Ploussard G, Soulié M, Pfister C, Van Agt S, Vincendeau S, Larue S, Rigaud J, Gaschignard N, Rouprêt M, et al. Members of Committee of Cancerology of the French Association of Urology (CCAFU). Pathologic findings in radical prostatectomy specimens from patients eligible for active surveillance with highly selective criteria: a multicenter study. Urology. 2012; 80:656–660.

18. Ploussard G, Salomon L, Xylinas E, Allory Y, Vordos D, Hoznek A, Abbou CC, de la Taille A. Pathological findings and prostate specific antigen outcomes after radical prostatectomy in men eligible for active surveillance--does the risk of misclassification vary according to biopsy criteria? J Urol. 2010; 183:539–544.

19. Kane CJ, Im R, Amling CL, Presti JC Jr, Aronson WJ, Terris MK, Freedland SJ. SEARCH Database Study Group. Outcomes after radical prostatectomy among men who are candidates for active surveillance: results from the SEARCH database. Urology. 2010; 76:695–700.

20. Han CS, Parihar JS, Kim IY. Active surveillance in men with low-risk prostate cancer: current and future challenges. Am J Clin Exp Urol. 2013; 1:72–82.

21. Berglund RK, Masterson TA, Vora KC, Eggener SE, Eastham JA, Guillonneau BD. Pathological upgrading and up staging with immediate repeat biopsy in patients eligible for active surveillance. J Urol. 2008; 180:1964–1967. discussion 7-8.

22. Kates M, Tosoian JJ, Trock BJ, Feng Z, Carter HB, Partin AW. Indications for intervention during active surveillance of prostate cancer: a comparison of the Johns Hopkins and Prostate Cancer Research International Active Surveillance (PRIAS) protocols. BJU Int. 2015; 115:216–222.

23. Conti SL, Dall'era M, Fradet V, Cowan JE, Simko J, Carroll PR. Pathological outcomes of candidates for active surveillance of prostate cancer. J Urol. 2009; 181:1628–1633. discussion 33-4.

24. Kim TH, Jeon HG, Choo SH, Jeong BC, Seo SI, Jeon SS, Choi HY, Lee HM. Pathological upgrading and upstaging of patients eligible for active surveillance according to currently used protocols. Int J Urol. 2014; 21:377–381.

25. Seo WI, Kang PM, Kang DI, Yoon JH, Kim W, Chung JI. Cancer of the Prostate Risk Assessment (CAPRA) Preoperative Score Versus Postoperative Score (CAPRA-S): ability to predict cancer progression and decision-making regarding adjuvant therapy after radical prostatectomy. J Korean Med Sci. 2014; 29:1212–1216.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download