Abstract

A 52-yr-old male was referred for progressive visual loss in the left eye. The decimal best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 0.01. Fundus examination revealed diffuse retinal pigment epithelial degeneration, focal yellow-white, infiltrative subretinal lesion with fuzzy border and a live nematode within the retina. Diffuse unilateral subacute neuroretinitis (DUSN) was diagnosed and the direct laser photocoagulation was performed to destroy the live nematode. During eight months after treatment, BCVA gradually improved to 0.2 along with the gradual restoration of outer retinal layers on SD-OCT. We report on the first case of DUSN in Korea. DUSN should be included in the differential diagnosis of unexplained unilateral visual loss in otherwise healthy subjects.

Diffuse unilateral subacute neuroretinitis (DUSN) is an inflammatory and infectious disease caused by yet unidentified species of nematodes (1, 2). These nematodes can be classified into two groups according to size; the smaller nematodes are usually 500-600 µm in size and believed to be the dog hookworm, Ancylostoma caninum (3, 4, 5), while the larger nematodes are the raccoon roundworm, Baylisascaris procyonis, and typically 1,000-2,000 µm in size (3, 6, 7, 8). The smaller nematodes are more common and usually endemic in the southeastern United States, the Caribbean, Venezuela, and Brazil (8, 9, 10). The larger nematodes are much less prevalent and have been reported in the midwestern United States, Europe, and Brazil (3, 8, 11, 12).

DUSN is more prominent in children and young adults without gender preference (1, 2). This condition is usually unilateral, rarely bilateral (1, 2, 6, 9). DUSN is characterized by progressive visual loss due to inflammatory changes in the retina, retinal pigment epithelium, retinal vessels and optic nerve (1, 2, 10, 11, 12). The pathogenesis involves a mechanical, inflammatory, and toxic tissue effect on the outer retina caused by worm by-products (1, 3). In addition, a more diffuse toxic reaction eventually affects the inner and outer retinal tissues (1, 3).

DUSN is most prevalent in the southeastern United States, the Caribbean, and South America, and some cases have been reported in Europe (1, 2, 4, 13, 14, 15). However, it has rarely been reported in Asian countries; only two cases of DUSN have been reported in India and China, respectively (16, 17). In this case report, we present the first case of DUSN in Korea.

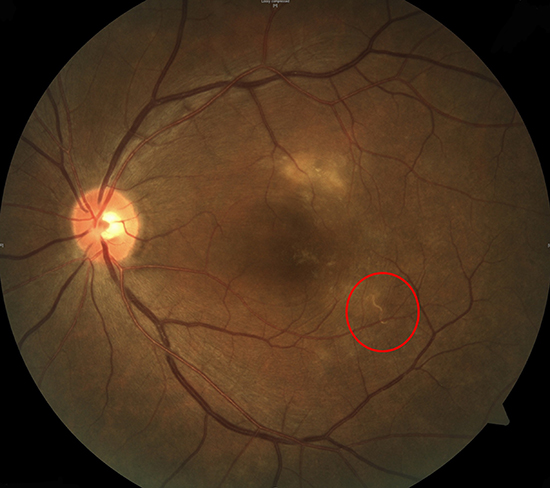

A 52-yr-old male patient was referred to the tertiary ophthalmology clinic for gradual deterioration of vision in the left eye for the past 10 days on February 1, 2013. The best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) in the left eye was 0.01 according to the decimal visual acuity chart. Slit-lamp examination showed the presence of fine cells in the anterior vitreous of the left eye. Fundus examination with an indirect ophthalmoscope revealed a yellow-white, infiltrative subretinal lesion with a fuzzy border superior to the fovea (Fig. 1A). In addition, a whitish line with a wavy curvature was found inferotemporal to the fovea (Fig. 1A). Spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) (Spectralis; Heidelberg Engineering; Heidelberg, Germany) of the left eye showed fluid accumulation in the epiretinal space of the fovea (Fig. 1B), with diffuse disruption of external limiting membrane (ELM) and photoreceptor layer at fovea (Fig. 1B). In addition, a cross-section SD-OCT image of the wavy line showed a 300-µm-wide, high-signal intensity mass beneath what appeared to be the internal limiting membrane (ILM) (Fig. 1C).

Based on our diagnosis of DUSN, further questions revealed that he habitually ate raw balloon flower roots. Serial fundus examination showed the nematode in the subretinal space, suggesting that the nematode can move through the entire retinal layer. For treatment, direct-laser photocoagulation was performed above the nematode. To prevent exacerbation of inflammation from by-products of the dead worm, 30 mg of systemic prednisolone combined with antihelminthic medication albendazole 400 mg twice per day was provided for 2 weeks following laser treatment. The nematode was not found after 2 weeks, and fundus examination indicated that the infiltrative lesion had resolved (Fig. 1D) on February 15, 2013. SD-OCT showed complete resolution of the epiretinal space and recovery of ELM (Fig. 1E). However, photoreceptor layer was not fully recovered (Fig. 1E).

At an 8-month follow-up visit, the BCVA significantly improved to 0.2 on October 12, 2013. Diffuse disruption of photoreceptor disruption on SD-OCT was much recovered when compared with previous SD-OCT findings at 2 weeks post-treatment, but not fully recovered (Fig. 1F), which explains the partial recovery of visual acuity.

DUSN is frequently reported in South and Central America, but not in Asia (1, 2, 4, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17). DUSN has never been reported in Korean population. In the present case, we promptly diagnosed and treated DUSN with direct photocoagulation, which resulted in progressive restoration of severely damaged photoreceptor layer on SD-OCT and improvement in visual acuity in a Korean man.

The exact pathogenesis of DUSN is still under investigation. As mentioned earlier, the causative worms are still under investigation, and various nematodes including Ancylostoma caninum have been suggested as causative worms for DUSN (3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8). In accordance of poorly identified causative worms, entry of causative worm is also unclear in DUSN. Previously, one study suggested that human infection is thought to result from ingestion of soil contaminated with larvae or eggs [20]. They presumed that the worm may hatch in the intestine and then migrates via blood stream to the subretinal space [20]. Although the exact life cycle and entry of the causative worm were unclear, the habitual eating of raw balloon flower roots contaminated with larvae or eggs of a worm may have led to DUSN in this case. However, further investigation is needed to confirm the exact entry of the causative worm in DUSN patients.

Early diagnosis and prompt treatment with direct photocoagulation is crucial to good visual outcome in DUSN (10, 11, 12, 18, 19). Early-stage DUSN is characterized by active inflammation of the optic nerve, vitreous, outer retina, and choroid. In this phase, early diagnosis and treatment can improve vision by preventing permanent damage (1, 10, 11, 18, 19). However, if DUSN is not detected or diagnosed at an early stage, permanent ocular changes, including optic atrophy, retinal arterial narrowing, and degenerative changes in the outer retina, can lead to permanent vision loss (1, 11, 12). A previous study of 121 patients with DUSN showed a visual improvement from 20/600 to 20/400 Snellen visual acuity (11). Among 121 patients, 112 (92.6%) presented at a late stage, which may explain the relatively poor, although statistically significant, visual outcome of these patients (11). Thus, recognition of the clinical characteristics of DUSN, careful investigation of the causative worm, and subsequent treatment are important for preventing vision loss in patients with DUSN.

Direct-laser photocoagulation is the treatment of choice for destroying the causative worm and for preventing further damage (3, 4, 12, 18). Photocoagulation does not exacerbate inflammation and results in prompt and permanent inactivation of DUSN (3, 4, 12, 18). Antihelminthic treatment with albendazole is another treatment option, especially when the causative nematode has not been identified (3).

SD-OCT is a valuable diagnostic and prognostic tool during the disease course of DUSN, allowing a more precise evaluation of the retinal layers (18, 19). In a previous case report, OCT detected fluid accumulation beneath the epiretinal membrane, identified a nematode, and showed widespread outer retinal disruption at an early stage of disease (19). After direct photocoagulation, progressive restoration of the photoreceptor layer was detected by OCT with concomitant visual improvement (19). Likewise, SD-OCT fluid accumulation and nematode was identified in epiretinal space on SD-OCT in our case. However, we also observed the live worm in the subretinal space before direct photocoagulation, which was moving through entire retinal layer. It has been well known that the causative worms propel themselves by a series of slow coiling and uncoiling movement or snake-like movement through entire retina, from the subretinal space to sub-ILM space (3). Thus, we could assume that successful elimination by direct photocoagulation prevented further retinal damage, especially photoreceptor layer and ELM. In addition, elimination of worm byproducts also prevents further toxic effect on outer retinal layer in this patient. However, severe disruption of photoreceptor and the ELM layers were already present on SD-OCT, which resulted in partial recovery of photoreceptor layer despite of successful treatment in this patient.

This case confirms that DUSN can occur in Korea. Identification of the live worm and direct photocoagulation at the early stage of DUSN resulted in progressive visual improvement. Consumption of unwashed root vegetables may provide a chance for infestation with larvae or eggs of DUSN-causing worms. DUSN should be included in the differential diagnosis of unexplained unilateral vision loss in an otherwise healthy subject. Prompt diagnosis and management are critical for preventing further retinal damage and may facilitate visual recovery.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Representative figures of the first Korean case with diffuse unilateral subacute neuroretinitis. A 52-yr-old male patient was referred to the tertiary ophthalmology clinic for gradual deterioration of vision in the left eye for the past 10 days. The best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) in the left eye was 0.01 according to the decimal visual acuity chart. (A) Fundus of the left eye shows a yellow-white, infiltrative subretinal lesion with a whitish nematode (arrow) inferotemporal to the fovea. (B) Spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) of the left eye shows fluid accumulation in the epiretinal space of the fovea (asterisk), with diffuse disruption of external limiting membrane (ELM) and photoreceptor layer at fovea. (C) Cross-section SD-OCT image of a nematode beneath the internal limiting membrane (ILM). Under the diagnosis of diffuse unilateral subacute neuroretinitis, direct laser photocoagulation was done to eliminate the nematode. (D) After two weeks, infiltrative lesion was resolved. Note the pigmented area due to direct laser photocoagulation. (E) SD-OCT shows complete resolution of fluid at sub-ILM space and recovery of ELM. However, photoreceptor layer was not fully recovered. (F) At an 8-month follow-up visit, the BCVA of the left eye improved as 0.2. Diffuse disruption of photoreceptor disruption on SD-OCT was much recovered. |

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This case report was presented as a poster at the 110th Annual meeting of Korean Ophthalmology Society in KINTEX, Seoul, Korea, November 1-3, 2013.

References

1. Gass JD, Braunstein RA. Further observations concerning the diffuse unilateral subacute neuroretinitis syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol. 1983; 101:1689–1697.

2. Gass JD, Gilbert WR Jr, Guerry RK, Scelfo R. Diffuse unilateral subacute neuroretinitis. Ophthalmology. 1978; 85:521–545.

3. Cortez RT, Ramirez G, Collet L, Giuliari GP. Ocular parasitic diseases: a review on toxocariasis and diffuse unilateral subacute neuroretinitis. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2011; 48:204–212.

4. de Souza EC, da Cunha SL, Gass JD. Diffuse unilateral subacute neuroretinitis in South America. Arch Ophthalmol. 1992; 110:1261–1263.

5. de Souza EC, Nakashima Y. Diffuse unilateral subacute neuroretinitis. Report of transvitreal surgical removal of a subretinal nematode. Ophthalmology. 1995; 102:1183–1186.

6. Goldberg MA, Kazacos KR, Boyce WM, Ai E, Katz B. Diffuse unilateral subacute neuroretinitis. Morphometric, serologic, and epidemiologic support for Baylisascaris as a causative agent. Ophthalmology. 1993; 100:1695–1701.

7. Kazacos KR, Raymond LA, Kazacos EA, Vestre WA. The raccoon ascarid. A probable cause of human ocular larva migrans. Ophthalmology. 1985; 92:1735–1744.

8. Cialdini AP, de Souza EC, Avila MP. The first South American case of diffuse unilateral subacute neuroretinitis caused by a large nematode. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999; 117:1431–1432.

9. de Souza EC, Abujamra S, Nakashima Y, Gass JD. Diffuse bilateral subacute neuroretinitis: first patient with documented nematodes in both eyes. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999; 117:1349–1351.

10. Garcia CA, Gomes AH, Garcia Filho CA, Vianna RN. Early-stage diffuse unilateral subacute neuroretinitis: improvement of vision after photocoagulation of the worm. Eye (Lond). 2004; 18:624–627.

11. de Amorim Garcia Filho CA, Gomes AH, de A Garcia Soares AC, de Amorim Garcia CA. Clinical features of 121 patients with diffuse unilateral subacute neuroretinitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012; 153:743–749.

12. Garcia CA, Gomes AH, Vianna RN, Souza Filho JP, Garcia Filho CA, Oréfice F. Late-stage diffuse unilateral subacute neuroretinitis: photocoagulation of the worm does not improve the visual acuity of affected patients. Int Ophthalmol. 2005; 26:39–42.

13. Cortez R, Denny JP, Muci-Mendoza R, Ramirez G, Fuenmayor D, Jaffe GJ. Diffuse unilateral subacute neuroretinitis in Venezuela. Ophthalmology. 2005; 112:2110–2114.

14. Naumann GO, Knorr HL. DUSN occurs in Europe. Ophthalmology. 1994; 101:971–972.

15. Yuen VH, Chang TS, Hooper PL. Diffuse unilateral subacute neuroretinitis syndrome in Canada. Arch Ophthalmol. 1996; 114:1279–1282.

16. Cai J, Wei R, Zhu L, Cao M, Yu S. Diffuse unilateral subacute neuroretinitis in China. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000; 118:721–722.

17. Venkatesh P, Sarkar S, Garg S. Diffuse unilateral subacute neuroretinitis: report of a case from the Indian subcontinent and the importance of immediate photocoagulation. Int Ophthalmol. 2005; 26:251–254.

18. Garcia Filho CA, Soares AC, Penha FM, Garcia CA. Spectral domain optical coherence tomography in diffuse unilateral subacute neuroretinitis. J Ophthalmol. 2011; 2011:285296.

19. Tarantola RM, Elkins KA, Kay CN, Folk JC. Photoreceptor recovery following laser photocoagulation and albendazole in diffuse unilateral subacute neuroretinitis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011; 129:669–671.

20. Ament CS, Young LH. Ocular manifestations of helminthic infections: onchocersiasis, cysticercosis, toxocariasis, and diffuse unilateral subacute neuroretinitis. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2006; 46:1–10.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download