Abstract

Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) is an increasingly common cause of acute hepatitis. We examined clinical features and types of liver injury of 65 affected patients who underwent liver biopsy according DILI etiology. The major causes of DILI were the use of herbal medications (43.2%), prescribed medications (21.6%), and traditional therapeutic preparations and dietary supplements (35%). DILI from herbal medications, traditional therapeutic preparations, and dietary supplements was associated with higher elevations in aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels than was DILI from prescription medications. The types of liver injury based on the R ratio were hepatocellular (67.7%), mixed (10.8%), and cholestatic (21.5%). Herbal medications and traditional therapeutic preparations were more commonly associated with hepatocellular liver injury than were prescription medications (P = 0.002). Herbal medications and traditional therapeutic preparations induce more hepatocellular DILI and increased elevations in AST and ALT than prescribed medications.

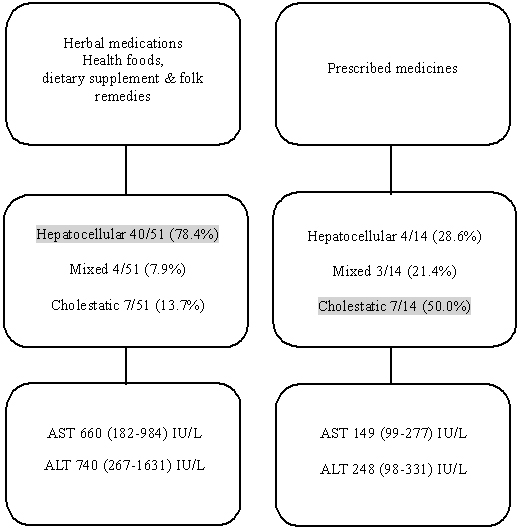

Graphical Abstract

Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) is caused by various prescribed medications, herbs, or other substances that lead to liver dysfunction in the absence of other etiologies (1). In Western countries, DILI accounts for 1.2%-6.6% of the cases of acute liver disease seen at tertiary referral centers and is one of the leading causes of acute liver failure, accounting for 13% of all cases (2). In Korea, the annual extrapolated incidence of DILI in hospitalized patients at a university hospital was calculated as 12/100,000 persons/year, and DILI is the most common cause of acute hepatitis (3). DILI can be classified into hepatocellular, cholestatic, and mixed patterns based on the ratio of serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) to alkaline phosphatase (ALP) (4).

The types of liver injury in DILI and the common causative agents have been documented in Western countries (56). However, most of these studies have been limited to assessing prescribed medications, such as antibiotics and anti-tuberculosis and the central nervous system (CNS) agents. The acceptance in Korea of oriental medicine and other traditional folk remedies as alternatives to modern medicine creates unique circumstances for studying DILI (7). These remedies, commonly called herbal medicines in Korea, are regarded as safe by many people and are often used to treat various conditions in the absence of regulation or expert advice. The number of individuals exposed to herbal medications is greater in Korea than in Western countries, suggesting that the causative agents that lead to DILI and the types of liver injury with which it is associated may differ from those in Western countries and resemble those in other Asian countries, such as China and Japan. The aim of this study was to investigate the clinical features and types of liver injury of affected patients who underwent liver biopsy according to DILI etiology.

A retrospective analysis was performed on the medical records of 163 patients who visited Soonchunhyang University Hospital (Seoul, Korea) with acute hepatitis diagnosed as DILI from July 2003 to February 2013. DILI was defined as aspartate aminotransferase (AST) or ALT≥3×upper normal limit (UNL) or total bilirubin (TB)≥2×UNL (8). We identified 65 cases of DILI that met the following inclusion criteria: 1) modified Roussel Uclaf Causality Assessment Method (RUCAM) score≥7; 2) >18 yr of age; and 3) DILI confirmed by biopsy. Histopathologic evaluation was performed by a single, experienced pathologist. History taking, radiologic tests including abdominal ultrasonography, and computed tomography (CT), and laboratory tests were performed to exclude etiologies other than DILI. All 65 patients underwent liver biopsy, and their baseline characteristics, etiology, chief complaints, comorbidities, laboratory findings, and histopathologic findings were analyzed. All patients with liver biopsy manifested moderate to severe liver disease. There was no patient who transferred for liver transplantation. Clinical mild hepatitis such as transient elevation of aminotransferase was excluded to do liver biopsy. During the study period, the number of mild hepatitis was a few.

DILI was defined as a liver injury that was caused by various medications, herbs, or other substances that led to liver dysfunction in the absence of other etiologies. In terms of the clinical characterization of DILI, the ratio of serum ALT to ALP was used as the R value ([ALT value/ALT UNL]/[ALP value/ALP UNL]). All DILI patients were classified into three groups by R value: hepatocellular DILI was defined as R≥5, cholestatic as R ≤2, and mixed as 2<R<5 (9).

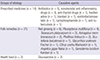

DILI was classified according to etiologic agent using these categories: medications, herbs, health foods or dietary supplements, and folk remedies. Medications were defined as medications prescribed by a medical doctor. Herbs were defined as herbal medications prescribed and compounded by a doctor of oriental medicine. Other traditional remedies that did not fit into the category of herbal medications were classified as folk remedies. Preparations intended to enhance the diet and provide nutrients, such as vitamins, minerals, fiber, fatty acids, and amino acids, were classified as health foods or dietary supplements. We combined the latter two classes into the category of health foods or dietary supplements and folk remedies. Factors associated with the etiology and pathologic findings of DILI, particularly the type of liver injury of each patient, his/her symptoms, and laboratory findings, were analyzed.

Basic descriptive statistics, including means, standard deviations (SDs), and ranges were used to characterize the participants. The number of patients with each etiology was tabulated, and percentages were calculated to reflect proportions of the total cohort. Modified RUCAM scores were used to determine the offending drug in each case of suspected idiosyncratic DILI. We used one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for data that were normally distributed and the Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric test for data that were not normally distributed. When the latter was used, we performed multiple-comparison testing using the Mann-Whitney test (Bonferroni's method) if the data from each group differed. For the evaluation of differences between the continuous variables among the groups, post-hoc analysis was done. For categorical variables, associations with outcome were assessed via the person chi-square test. Results were considered statistically significant when the P value was<0.05. All statistical analyses were performed with statistical software (SPSS, ver. 17.0, SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

A total of 163 patients were suspected to have DILI. We excluded 98 patients who were<18 yr old, had a modified RUCAM score<7, or who did not undergo a liver biopsy. After excluding these 98 patients, the medical records of 65 eligible patients were reviewed retrospectively (Fig. 1).

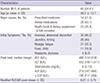

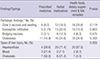

Table 1 shows baseline characteristics of enrolled patients. The incidence of DILI was higher in females (n=41) than in males (n=24), and the mean age of the patients was 48.2±13.1 yr. The major causes of DILI were the use of herbal medications (43.2%), prescription medications (21.6%), and traditional therapeutic preparations and dietary supplements (35%). At the time of admission, patients presented with various symptoms, such as anorexia and abdominal discomfort (46.2%), jaundice and itching (40%), myalgia and fatigue (32.3%), fever and chills (16.9%), as well as headache and dizziness (6.2%). The mean modified RUCAM score of all enrolled patients was 8.01±0.75 (Table 1). The causative agents in each etiological group are presented in Table 2.

The following peak laboratory findings were recorded in the study patients: AST, 488 (150-919) IU/L; ALT, 552 (190-1,511) IU/L; total bilirubin, 8 (2-13) mg/dL; ALP, 219 (161-484) IU/L; and γ-glutamyl transpeptidase 195 (111-289) IU/L (Table 1). The mean AST level of each causative agent were as follows: 764.64±560.96 IU/L for herbal medications, 223.61±210.10 IU/L for prescribed medications, and 702.18±546.59 IU/L for traditional therapeutic preparations and dietary supplements. The mean ALT level was 950.36±659.53 IU/L for those taking herbal medications, 263.00±176.36 IU/L for those taking prescription medications, and 1,271.46±931.84 IU/L for those taking traditional therapeutic preparations and dietary supplements (Table 3). These results demonstrate that DILI from herbal medications and traditional therapeutic preparations and dietary supplements shows higher AST (P=0.009) and ALT (P=0.001) level than that from prescription medications (Fig. 2). However, we found no significant differences in ALP (P=0.304), the AST/ALT ratio (P=0.407), prothrombin time (P=0.184), total bilirubin (P=0.521), and γ-GPT (P=0.630) (Table 3). Patients with AST >600 IU/L accounted for 7.7% (1/13) of the group receiving prescribed medications group, 64% (16/25) of the group receiving herbal medications, and 48% (13/27) of the group receiving traditional therapeutic preparations and dietary supplements (P=0.001). Patients with ALT >600 IU/L accounted for 7.7% (1/13) of those taking prescribed medications, 60% (15/25) of those taking herbal medications, and 56% (15/27) of those taking traditional therapeutic preparations and dietary supplements (P=0.005) (Table 3).

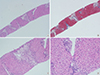

The types of liver injury based on the R ratio ([ALT/UNL]/[ALP/UNL]) were hepatocellular (67.7%), mixed (10.8%), and cholestatic (21.5%). Among patients whose DILI was due to herbal medication, the most common type of liver injury was hepatocellular (20/28, 71.4%) and the same result was observed with health foods or dietary supplements and folk remedies group (20/23, 87.0%). Among those receiving prescription medications, there was an even distribution of the types of liver injury: hepatocellular 28.6%, mixed 21.4%, cholestatic 50.0%. So, higher incidence of hepatocellular type was observed in herbal medication and health foods or dietary supplements and folk remedies groups than in prescription medication group (P=0.005) (Table 4). The main pathologic findings were cholestasis (66.2%), zone 3 necrosis and swelling (53.8%), increased eosinophilic infiltration (43.1%), and bridging necrosis (21.5%). A correlation between pathologic findings and etiology was not found in this study (Table 4). Main pathologic findings of drug induced liver injury are demonstrated in Fig. 2. However, higher incidence of hepatocellular type liver injury was observed in herbal medications and health foods or dietary supplements and folk remedies groups than in prescription medication group (P=0.005). All patients were recovered without complication after conservative treatment.

The incidence of drug-induced liver injury was recently reported in a nationwide multicenter Korean study (10). In our study, we analyzed the relationship between etiology and type of liver injury. Our results indicated that prescription medications accounted for 27.3% of DILI cases, herbs (including herbal medications) accounted for 40.1% of cases, and folk remedies and dietary supplements accounted for 22.3% of cases. The patterns of liver injury associated with each type of etiology differed somewhat from those found in a previous nationwide Korean study. Suk et al. (10) reported the most common pattern of liver injury associated with herbs was hepatocellular and that the most common pattern associated with folk remedies and dietary supplements was cholestatic. However, in our study, the most common pattern of liver injury for herbs and folk remedies and dietary supplements was hepatocellular. The etiology of DILI in Western countries differs from that in Asian countries, especially Korea and China. The causative agents of DILI in Western countries are primarily prescription medications, such as antibiotics, analgesics, and CNS agents, and only 0%-9% of cases had etiologies other than prescription medications (1112). The components of prescription medications are generally well known (13), whereas the exact ingredients of the herbs and folk remedies used in oriental medicine are more difficult to identify. Thus, the widely-used method of DILI classification that relies on R-values would not be a useful standard in Asian compared with in Western countries, which we believe accounts for differences between our study and the recent nationwide DILI study in Korea (10). A standard classification will require cooperation among the government, physicians, and doctors of oriental medicine in the service of identifying the specific ingredients of herbs and folk remedies.

In our study, the increase in aminotransferase levels in DILI significantly differed according to causative agent. The type of liver injury caused by herbal medications and traditional therapeutic preparations and dietary supplements was predominantly hepatocellular, and these were more likely to cause this type of injury than were prescription medications. A hepatocellular pattern indicates a greater aminotransferase elevation because, by definition, ALT is elevated five-fold compared with ALP (1415). The incidence of aminotransferase elevation may be greater with herbal medications and traditional therapeutic preparations and dietary supplements than with prescription medications because the R value is defined by ALT. However, data from our study indicate that both ALT and AST can be useful for predicting the pattern of livery injury.

Our study has several limitations. First, it used a single-center, retrospective design. However, due to the nature of DILI, it would be difficult to design a prospective study with a design that substantially differed from our retrospective design. Additionally, the number of patients in our study was sufficient to derive a conclusion from the data. Second, because all of our patients recovered completely, we could not compare the prognosis of the patients according to causative agents or types of liver injury. Third, the hospital stay of each patient was not same because patients who were diagnosed with DILI due to prescribed medication were admitted to the hospital earlier in the course of DILI than those due to herbal medications or traditional therapeutic preparations and dietary supplements. They generally did not visit the hospital until visible jaundice or detectable symptoms occurred. In the last, in our study, all enrolled patients took liver biopsy which confirmed moderate to severe liver disease in all patients. No patients were transferred for liver transplantation. Clinically mild hepatitis patients with transient elevation of aminotransferase were excluded to do liver biopsy. During the study period, the number of mild hepatitis was a few. Therefore, we think the selection bias might be minimal.

In conclusion, the etiology of DILI in Korea was quite different from that in western countries. The pathologic findings of the patients included in this study differed from that of another Korean DILI study. We presume that the complexity of the ingredients of causative agents is responsible for the conclusion as aminotransferase levels are higher among those receiving herbal medications and traditional therapeutic preparations and dietary supplements than among those receiving prescribed medications. And this could account for the increased incidence of hepatocellular liver injury.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 2Main pathologic findings of drug induced liver injury. (A) There are several centrilobular confluent necrosis at the acinar zone III with bridging necrosis connected to the adjacent vascular structure (H&E stain, × 40). (B) Trichrome stain showed enlarged portal tract with minimal portal fibrosis (Trichrome stain, × 40). (C) The necrotic acinar zone III areas are mostly infiltrated by lipofusin pigment laden histiocytes. There is also surrounding chronic inflammatory cell infiltration (H&E stain, × 100). (D) Focal necrosis and acidophilic body formation of the hepatocytes with Kupffer cell hyperplasia are also present (H&E stain, × 200). |

Table 1

Baseline characteristics of the enrolled patients

Table 2

Causative agents according to each group of etiology

Table 3

Laboratory values of each patient group with the 3 major causative agents

Table 4

Pathologic findings and types of liver injury according to the causative agents

References

1. Vuppalanchi R, Liangpunsakul S, Chalasani N. Etiology of new-onset jaundice: how often is it caused by idiosyncratic drug-induced liver injury in the United States? Am J Gastroenterol. 2007; 102:558–562.

2. Ostapowicz G, Fontana RJ, Schiødt FV, Larson A, Davern TJ, Han SH, McCashland TM, Shakil AO, Hay JE, Hynan L, et al. Results of a prospective study of acute liver failure at 17 tertiary care centers in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2002; 137:947–954.

3. Suk KT, Kim DJ. Drug-induced liver injury: present and future. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2012; 18:249–257.

4. Au JS, Navarro VJ, Rossi S. Review article: Drug-induced liver injury--its pathophysiology and evolving diagnostic tools. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011; 34:11–20.

5. Andrade RJ, Lucena MI, Fernández MC, Pelaez G, Pachkoria K, Garcia-Ruiz E, García-Muñoz B, González-Grande R, Pizarro A, Duán JA, et al. Drug-induced liver injury: an analysis of 461 incidences submitted to the Spanish registry over a 10-year period. Gastroenterology. 2005; 129:512–521.

6. Chalasani N, Fontana RJ, Bonkovsky HL, Watkins PB, Davern T, Serrano J, Yang H, Rochon J. Drug Induced Liver Injury Network (DILIN). Causes, clinical features, and outcomes from a prospective study of drug-induced liver injury in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2008; 135:1924–1934. 1934.e1–1934.e4.

7. Ju HY, Jang JY, Jeong SW, Woo SA, Kong MG, Jang HY, Lee SH, Kim SG, Cha SW, Kim YS, et al. The clinical features of drug-induced liver injury observed through liver biopsy: focus on relevancy to autoimmune hepatitis. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2012; 18:213–218.

8. Reuben A. Hy's law. Hepatology. 2004; 39:574–578.

9. Fontana RJ, Seeff LB, Andrade RJ, Björnsson E, Day CP, Serrano J, Hoofnagle JH. Standardization of nomenclature and causality assessment in drug-induced liver injury: summary of a clinical research workshop. Hepatology. 2010; 52:730–742.

10. Suk KT, Kim DJ, Kim CH, Park SH, Yoon JH, Kim YS, Baik GH, Kim JB, Kweon YO, Kim BI, et al. A prospective nationwide study of drug-induced liver injury in Korea. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012; 107:1380–1387.

11. De Valle MB, Av Klinteberg V, Alem N, Olsson R, Björnsson E. Drug-induced liver injury in a Swedish University hospital out-patient hepatology clinic. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006; 24:1187–1195.

12. Teschke R, Schulze J, Schwarzenboeck A, Eickhoff A, Frenzel C. Herbal hepatotoxicity: suspected cases assessed for alternative causes. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013; 25:1093–1098.

13. Bunchorntavakul C, Reddy KR. Review article: herbal and dietary supplement hepatotoxicity. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013; 37:3–17.

14. Xu HM, Chen Y, Xu J, Zhou Q. Drug-induced liver injury in hospitalized patients with notably elevated alanine aminotransferase. World J Gastroenterol. 2012; 18:5972–5978.

15. Devarbhavi H, Dierkhising R, Kremers WK, Sandeep MS, Karanth D, Adarsh CK. Single-center experience with drug-induced liver injury from India: causes, outcome, prognosis, and predictors of mortality. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010; 105:2396–2404.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download