1. Grinda JM, Chevalier P, D'Attellis N, Bricourt MO, Berrebi A, Guibourt P, Fabiani JN, Deloche A. Fulminant myocarditis in adults and children: bi-ventricular assist device for recovery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2004; 26:1169–1173.

2. Mody KP, Takayama H, Landes E, Yuzefpolskaya M, Colombo PC, Naka Y, Jorde UP, Uriel N. Acute mechanical circulatory support for fulminant myocarditis complicated by cardiogenic shock. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2014; 7:156–164.

3. Nahum E, Dagan O, Lev A, Shukrun G, Amir G, Frenkel G, Katz J, Michel B, Birk E. Favorable outcome of pediatric fulminant myocarditis supported by extracorporeal membranous oxygenation. Pediatr Cardiol. 2010; 31:1059–1063.

4. Ghelani SJ, Spaeder MC, Pastor W, Spurney CF, Klugman D. Demographics, trends, and outcomes in pediatric acute myocarditis in the United States, 2006 to 2011. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012; 5:622–627.

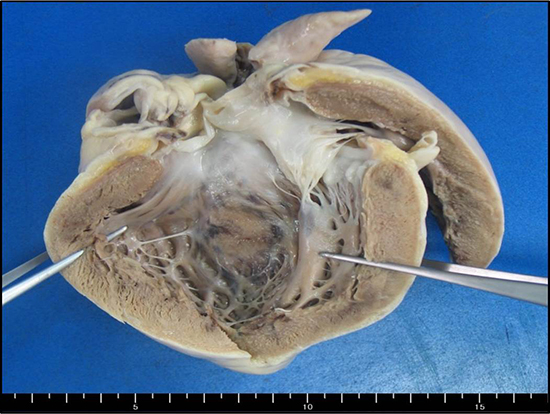

5. Aretz HT. Myocarditis: the Dallas criteria. Hum Pathol. 1987; 18:619–624.

6. McCarthy RE 3rd, Boehmer JP, Hruban RH, Hutchins GM, Kasper EK, Hare JM, Baughman KL. Long-term outcome of fulminant myocarditis as compared with acute (nonfulminant) myocarditis. N Engl J Med. 2000; 342:690–695.

7. Wilmot I, Morales DL, Price JF, Rossano JW, Kim JJ, Decker JA, McGarry MC, Denfield SW, Dreyer WJ, Towbin JA, et al. Effectiveness of mechanical circulatory support in children with acute fulminant and persistent myocarditis. J Card Fail. 2011; 17:487–494.

8. Mahrholdt H, Goedecke C, Wagner A, Meinhardt G, Athanasiadis A, Vogelsberg H, Fritz P, Klingel K, Kandolf R, Sechtem U. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance assessment of human myocarditis: a comparison to histology and molecular pathology. Circulation. 2004; 109:1250–1258.

9. Pankuweit S, Portig I, Eckhardt H, Crombach M, Hufnagel G, Maisch B. Prevalence of viral genome in endomyocardial biopsies from patients with inflammatory heart muscle disease. Herz. 2000; 25:221–226.

10. Narula N, McNamara DM. Endomyocardial biopsy and natural history of myocarditis. Heart Fail Clin. 2005; 1:391–406.

11. Chen YS, Yu HY, Huang SC, Chiu KM, Lin TY, Lai LP, Lin FY, Wang SS, Chu SH, Ko WJ. Experience and result of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in treating fulminant myocarditis with shock: what mechanical support should be considered first. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2005; 24:81–87.

12. Song SW, Yang HS, Lee S, Youn YN, Yoo KJ. Earlier application of percutaneous cardiopulmonary support rescues patients from severe cardiopulmonary failure using the APACHE III scoring system. J Korean Med Sci. 2009; 24:1064–1070.

13. Lieberman EB, Hutchins GM, Herskowitz A, Rose NR, Baughman KL. Clinicopathologic description of myocarditis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991; 18:1617–1626.

14. Haas GJ. Etiology, evaluation, and management of acute myocarditis. Cardiol Rev. 2001; 9:88–95.

15. Freund MW, Kleinveld G, Krediet TG, van Loon AM, Verboon-Maciolek MA. Prognosis for neonates with enterovirus myocarditis. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2010; 95:F206–F212.

16. Rupprecht L, Flörchinger B, Schopka S, Schmid C, Philipp A, Lunz D, Müller T, Camboni D. Cardiac decompression on extracorporeal life support: a review and discussion of the literature. ASAIO J. 2013; 59:547–553.

17. Adebo OA, Lun KC, Lee CN, Chao TC. Age-related changes in normal Chinese hearts. Chin Med J (Engl). 1994; 107:88–94.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download