1. Jensen TS, Baron R, Haanpää M, Kalso E, Loeser JD, Rice AS, Treede RD. A new definition of neuropathic pain. Pain. 2011; 152:2204–2205.

2. Haanpää M, Attal N, Backonja M, Baron R, Bennett M, Bouhassira D, Cruccu G, Hansson P, Haythornthwaite JA, Iannetti GD, et al. NeuPSIG guidelines on neuropathic pain assessment. Pain. 2011; 152:14–27.

3. Jones RC 3rd, Backonja MM. Review of neuropathic pain screening and assessment tools. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2013; 17:363.

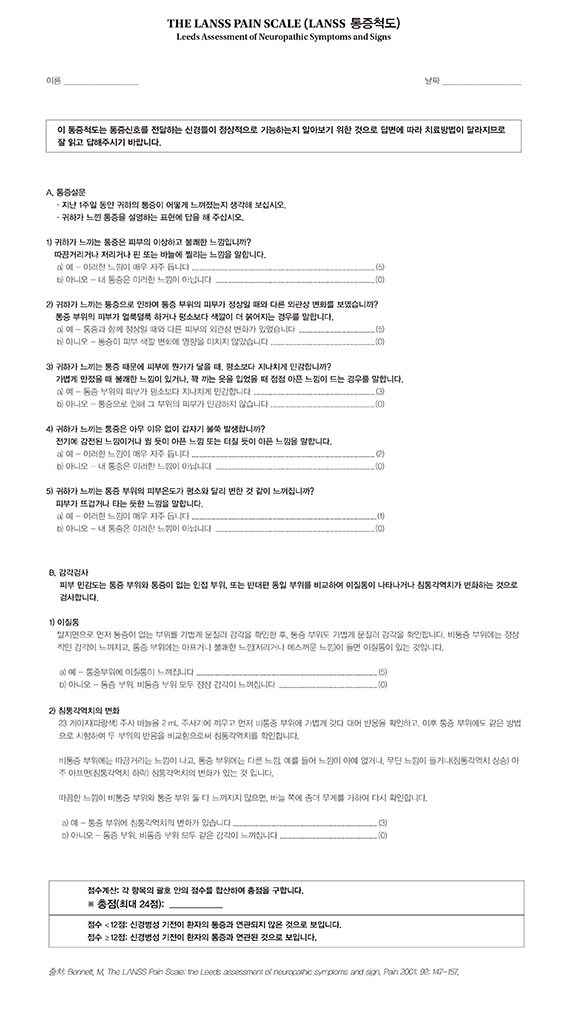

4. Bennett M. The LANSS Pain Scale: the Leeds assessment of neuropathic symptoms and signs. Pain. 2001; 92:147–157.

5. Yucel A, Senocak M, Kocasoy Orhan E, Cimen A, Ertas M. Results of the Leeds assessment of neuropathic symptoms and signs pain scale in Turkey: a validation study. J Pain. 2004; 5:427–432.

6. Pérez C, Gálvez R, Insausti J, Bennett M, Ruiz M, Rejas J. Group for the study of Spanish validation of LANSS. Linguistic adaptation and Spanish validation of the LANSS (Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs) scale for the diagnosis of neuropathic pain. Med Clin (Barc). 2006; 127:485–491.

7. Hallström H, Norrbrink C. Screening tools for neuropathic pain: can they be of use in individuals with spinal cord injury? Pain. 2011; 152:772–779.

8. Schestatsky P, Félix-Torres V, Chaves ML, Câmara-Ehlers B, Mucenic T, Caumo W, Nascimento O, Bennett MI. Brazilian Portuguese validation of the Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs for patients with chronic pain. Pain Med. 2011; 12:1544–1550.

9. Barbosa M, Bennett MI, Verissimo R, Carvalho D. Cross-cultural psychometric assessment of the Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs (LANSS) pain scale in the Portuguese population. Pain Pract. 2014; 14:620–624.

10. Li J, Feng Y, Han J, Fan B, Wu D, Zhang D, Du D, Li H, Lim J, Wang J, et al. Linguistic adaptation, validation and comparison of 3 routinely used neuropathic pain questionnaires. Pain Physician. 2012; 15:179–186.

11. Bennett MI, Bouhassira D. Epidemiology of neuropathic pain: can we use the screening tools? Pain. 2007; 132:12–13.

12. Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000; 25:3186–3191.

13. Guillemin F, Bombardier C, Beaton D. Cross-cultural adaptation of health-related quality of life measures: literature review and proposed guidelines. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993; 46:1417–1432.

14. Treede RD, Jensen TS, Campbell JN, Cruccu G, Dostrovsky JO, Griffin JW, Hansson P, Hughes R, Nurmikko T, Serra J. Neuropathic pain: redefinition and a grading system for clinical and research purposes. Neurology. 2008; 70:1630–1635.

15. Terwee CB, Bot SD, de Boer MR, van der Windt DA, Knol DL, Dekker J, Bouter LM, de Vet HC. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007; 60:34–42.

16. Yun DJ, Oh J, Kim BJ, Lim JG, Bae JS, Jeong D, Joo IS, Park MS, Kim BJ. Development of Korean Neuropathic Pain Questionnaire for neuropathic pain screening and grading: a pilot study. J Korean Neurol Assoc. 2012; 30:15–25.

17. O'Connor AB. Neuropathic pain: quality-of-life impact, costs and cost effectiveness of therapy. Pharmacoeconomics. 2009; 27:95–112.

18. Schestatsky P, Gerchman F, Valls-Solé J. Neurophysiological tools for small fiber assessment in painful diabetic neuropathy (comment letter). Pain Med. 2009; 10:601. author reply 2.

19. DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics. 1988; 44:837–845.

20. Backonja MM. Need for differential assessment tools of neuropathic pain and the deficits of LANSS pain scale. Pain. 2002; 98:229–230. author reply 30-1

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download