1. Kim SK. How to save surgical residents in crisis. J Korean Surg Soc. 2009; 76:207–214.

2. Balch CM, Shanafelt T. Combating stress and burnout in surgical practice: a review. Thorac Surg Clin. 2011; 21:417–430.

3. BAner JG 4th, Khan Z, Babu M, Hamed O. Stress, burnout, and maladaptive coping: strategies for surgeon well-being. Bull Am Coll Surg. 2011; 96:17–22.

4. Harms BA, Heise CP, Gould JC, Starling JR. A 25-year single institution analysis of health, practice, and fate of general surgeons. Ann Surg. 2005; 242:520–526. discussion 6-9.

5. Yeo H, Viola K, Berg D, Lin Z, Nunez-Smith M, Cammann C, Bell RH Jr, Sosa JA, Krumholz HM, Curry LA. Attitudes, training experiences, and professional expectations of US general surgery residents: a national survey. JAMA. 2009; 302:1301–1308.

6. Sameer-ur-Rehman , Kumar R, Siddiqui N, Shahid Z, Syed S, Kadir M. Stress, job satisfaction and work hours in medical and surgical residency programmes in private sector teaching hospitals of Karachi, Pakistan. J Pak Med Assoc. 2012; 62:1109–1112.

7. Weinstein DF. Duty hours for resident physicians--tough choices for teaching hospitals. N Engl J Med. 2002; 347:1275–1278.

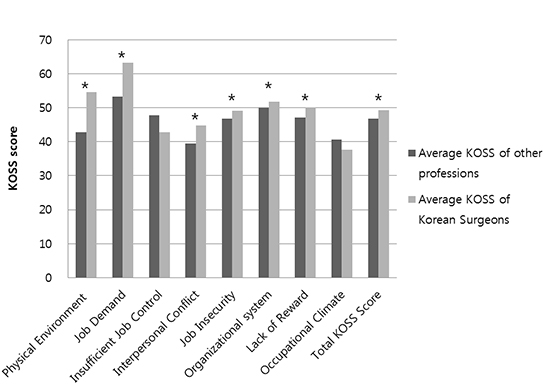

8. Chang SJ, Koh SB, Kang D, Kim SA, Kang MG, Lee CG, Chung JJ, Cho JJ, Son M, Chae CH, et al. Developing an occupational stress scale for Korean employees. Korean J Occup Environ Med. 2005; 17:297–317.

9. Kang SH, Boo YJ, Lee JS, Ji WB, Yoo BE, You JY. Analysis of the occupational stress of Korean surgeons: a pilot study. J Korean Surg Soc. 2013; 84:261–266.

10. Maslach C, Jackson SE. The measurement of experienced burnout. J Organ Behv. 1981; 2:99–113.

11. Shanafelt TD, Oreskovich MR, Dyrbye LN, Satele DV, Hanks JB, Sloan JA, Balch CM. Avoiding burnout: the personal health habits and wellness practices of US surgeons. Ann Surg. 2012; 255:625–633.

12. Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps GJ, Russell T, Dyrbye L, Satele D, Collicott P, Novotny PJ, Sloan J, Freischlag JA. Burnout and career satisfaction among American surgeons. Ann Surg. 2009; 250:463–471.

13. Cho JJ, Kim JY, Chang SJ, Fiedler N, Koh SB, Crabtree BF, Kang DM, Kim YK, Choi YH. Occupational stress and depression in Korean employees. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2008; 82:47–57.

14. Balch CM, Oreskovich MR, Dyrbye LN, Colaiano JM, Satele DV, Sloan JA, Shanafelt TD. Personal consequences of malpractice lawsuits on American surgeons. J Am Coll Surg. 2011; 213:657–667.

15. Shanafelt TD, Novotny P, Johnson ME, Zhao X, Steensma DP, Lacy MQ, Rubin J, Sloan J. The well-being and personal wellness promotion strategies of medical oncologists in the North Central Cancer Treatment Group. Oncology. 2005; 68:23–32.

16. Gerber M, Brand S, Elliot C, Holsboer-Trachsler E, Pühse U, Beck J. Aerobic exercise training and burnout: a pilot study with male participants suffering from burnout. BMC Res Notes. 2013; 6:78.

17. West CP, Tan AD, Habermann TM, Sloan JA, Shanafelt TD. Association of resident fatigue and distress with perceived medical errors. JAMA. 2009; 302:1294–1300.

18. Balch CM, Shanafelt TD. Burnout among surgeons: whether specialty makes a difference. Arch Surg. 2011; 146:385–386.

19. Balch CM. Comanaging an organ transplantation and melanoma. Arch Surg. 2011; 146:1347–1348.

20. Benson S, Sammour T, Neuhaus SJ, Findlay B, Hill AG. Burnout in Australasian Younger Fellows. ANZ J Surg. 2009; 79:590–597.

21. Kuerer HM, Eberlein TJ, Pollock RE, Huschka M, Baile WF, Morrow M, Michelassi F, Singletary SE, Novotny P, Sloan J, et al. Career satisfaction, practice patterns and burnout among surgical oncologists: report on the quality of life of members of the Society of Surgical Oncology. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007; 14:3043–3053.

22. Childs E, de Wit H. Regular exercise is associated with emotional resilience to acute stress in healthy adults. Front Physiol. 2014; 5:161.

23. Kellerman SE, Herold J. Physician response to surveys. A review of the literature. Am J Prev Med. 2001; 20:61–67.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download