1. Park JS, Kim YH. The history of occupational health service in Korea. Ind Health. 1998; 36:393–401.

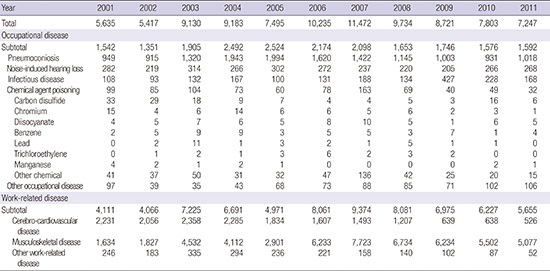

2. Kang SK, Kim EA. Occupational diseases in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2010; 25:S4–S12.

4. Song J, Kim I, Choi BS. The scope and specific criteria for compensation for occupational diseases in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2014; 29:S32–S39.

7. Kim EA, Kang SK. Historical review of the list of occupational disease recommendation by the International Labour Organization (ILO). Ann Occup Environ Med. 2013; 25:14.

8. Ministry of Labor. The footsteps of amending Labor Standard Act and Decree. Gwacheon: Ministry of Labor;2008.

9. Established Rule of Ministry of Labor of the Republic of Korea, Ministry of Labor Rule No. 71, (27 August 1982). Seoul: 1982.

10. Established Rule of Ministry of Labor of the Republic of Korea, Ministry of Labor Rule No. 92, (20 October 1983). Seoul: 1983.

11. Established Rule of Ministry of Labor of the Republic of Korea, Ministry of Labor Rule No. 167, (5 December 1989). Gwacheon: 1989.

12. Established Rule of Ministry of Labor of the Republic of Korea, Ministry of Labor Rule No. 205, (1 November 1991). Gwacheon: 1991.

13. Established Rule of Ministry of Labor of the Republic of Korea, Ministry of Labor Rule No. 234, (6 May 1993). Gwacheon: 1993.

14. Established Rule of Ministry of Labor of the Republic of Korea, Ministry of Labor Rule No. 247, (28 July 1994). Gwacheon: 1994.

17. Choi JW, Jang SH. A review on the carbon disulfide poisoning experiences in Korean. Korean J Occup Environ Med. 1991; 3:11–20.

18. Lee E, Kim S, Kim H, Kim K, Yum YT. Carbon disulfide poisoning in Korea with social and historical background. Korean J Occup Health. 1996; 38:155–161.

19. Jeong WS, Cheon JS, Chang HI. A case of organic mental disorder associated with subacute mercury poisoning. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc. 1985; 24:168–172.

20. Park HS, Lim HS, Huh BL, Han HK, Hwang YS, Moon HR, Hong KY. A case report of a fatal mercury poisoning. J Korean Acad Fam Med. 1991; 12:66–71.

21. Lee BK. Occupational lead exposure of storage battery workers in Korea. Br J Ind Med. 1982; 39:283–289.

22. Park CY, Roh YM, Koo JW, Lee SH. Manganese exposure in ore crushing. Korean J Occup Environ Med. 1991; 3:111–118.

23. Lim Y, Yim HW, Kim KA, Yun IG. Review on the manganese poisoning. Korean J Occup Health. 1991; 30:13–18.

24. Park TH, Kim JI, Son JE, Kim JK, Kim HS, Jung KY, Kim JY. Two cases of neuropathy by methyl bromide intoxication during fumigation. Korean J Occup Environ Med. 2000; 12:547–553.

25. Kim EA, Kang SK. Occupational neurological disorders in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2010; 25:S26–S35.

26. Kim YJ, Kim Y, Jeong KS, Sim CS, Choy N, Kim J, Eum JB, Nakajima Y, Endo Y, Yoo CI. A case of acute organotin poisoning. Korean J Occup Environ Med. 2006; 18:255–262.

27. Kang SK, Jang JY, Rhee KY, Chung HK. A study on the liver dysfunction due to dimethylformaide. Korean J Occup Environ Med. 1991; 3:58–63.

28. Kim SK, Lee SJ, Chung KC. A suspicious case of dimethylformaide induced fulminant hepatitis on synthetic leather workers. Korean J Occup Environ Med. 1995; 7:186–190.

29. Heo JH, Lee KI, Han SG, Kim HJ, Pau YM, Whang YH, Kang PJ, Kim CH, Cho SR. A case of fulminant hepatitis due to dimethylformamide. Korean J Gastroenterol. 1999; 34:547–550.

30. Roh JR, Sohn JG, Kim JH, Park SJ. A case of acute toxic hepatitis induced by brief exposure to dimethylformaide. Korean J Occup Environ Med. 2005; 17:144–148.

31. Joo MD, Sohn YD, Choi WI. A case of toxic hepatitis after the exposure of dimethylformamide. J Korean Soc Emerg Med. 2006; 17:515–518.

32. Lim HS, Lee K. Health care plan for hydrogen fluoride spill, Gumi, Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2012; 27:1283–1284.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download