Abstract

Recent advances in dialysis and a multidisciplinary approach to pregnant patients with advanced chronic kidney disease provide a better outcome. A 38-yr-old female with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) became pregnant. She was undergoing hemodialysis (HD) and her kidneys were massively enlarged, posing a risk of intrauterine fetal growth restriction. By means of intensive HD and optimal management of anemia, pregnancy was successfully maintained until vaginal delivery at 34.5 weeks of gestation. We discuss the special considerations involved in managing our patient with regard to the underlying ADPKD and its influence on pregnancy.

Pregnancy in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) is rare, and kidney disease before pregnancy is associated with poor fetal outcome. However, the outcome of pregnancy in dialysis patients has been much improved, and the overall rate of successful fetal outcome is reported to be 76% (1). This is mainly due to a multidisciplinary approach that incorporates intensive dialysis and aggressive management of anemia and hypertension.

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) is the most common inherited renal disease, and approximately half of the patients progress to ESRD by age of 60 (2). With regard to pregnancy, fertility is not affected by ADPKD in patients with normal renal function (3, 4). However, as kidney cysts grow, hypertension and deterioration of kidney function develop, which adversely affect pregnancy. In addition, massively enlarged kidneys may occupy the abdominal and pelvic cavities, preventing the normal growth of placenta and fetus. We present a case of successful pregnancy in an ADPKD patient on hemodialysis (HD).

A 38-yr-old primigravida female on HD presented with amenorrhea in May 2011. She had been diagnosed with ADPKD 6 yr ago. She started HD 3 times a week after 3 yr of her initial diagnosis. At the time of presentation, she was normotensive and had been prescribed aspirin (100 mg daily), multivitamins, calcium-based phosphate binders, and erythropoietin (1,000 units every HD session). Her dry weight was 53.3 kg and interdialytic weight gain was 1.5-2.5 kg. Her mother had ADPKD and was also on HD.

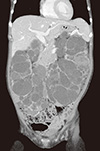

She was confirmed to be 8 weeks pregnant by pelvic ultrasound and beta-hCG test. The physical examination revealed a blood pressure (BP) of 137/85 mm Hg and a regular heart rate of 107 beats per minute. Laboratory findings at presentation were as follows: hemoglobin (Hb) of 10.4 g/dL; hematocrit (Hct) 31.5%; blood urea nitrogen (BUN) 56.9 mg/dL; serum creatinine (Cr) 9.0 mg/dL; total protein 5.9 g/dL; serum albumin 3.7 g/dL; serum calcium 9.3 mg/dL; serum phosphorus 3.3 mg/dL; potassium 5.5 mM/L; and normal liver function. Her 24-hr urine volume was about 1 liter. The computed tomography scan taken 2 yr ago showed bilaterally enlarged kidneys filled with numerous renal cysts along with only a few liver cysts (Fig. 1). Total kidney volume was measured to be 5,970 mL.

She was managed by a multidisciplinary team approach to optimize the patient and fetal outcomes. Firstly, the risk of pregnancy in a dialysis patient and the need for intensive dialysis were discussed with her family. Secondly, our team evaluated the risk of stunted intrauterine fetal growth by her massively enlarged kidneys. We considered a unilateral nephrectomy at the second trimester to secure the intraabdominal space, but the risk was determined to outweigh the benefits in this case. Finally, genetic counseling about the fetus's risk of inheriting ADPKD and prenatal genetic diagnosis was provided but declined by the patient.

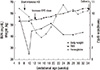

At 10 weeks gestation, HD prescription was changed to 4-hr treatments 4-5 times a week, and a predialysis BUN less than 50 mg/dL was targeted. Throughout pregnancy, predialysis BUN was maintained at 25.1-51.3 mg/dL. Standard unfractionated heparin was used for anticoagulation. Her BP was well controlled without any antihypertensive medication: systolic BP remained at 110-140 mmHg and diastolic was consistently at 60-80 mmHg. Anemia was managed with recombinant human erythropoietin and intravenous iron without transfusion. Erythropoietin doses were adjusted to target a maternal Hb between 10-11 g/dL. The median dose was 18,000 IU/week (range, 5,000-26,000 IU/week) during gestational weeks 12-36. In addition, 100 mg intravenous iron sucrose was administered every session during gestational weeks 19-22. The hemoglobin level was maintained above 9.5 g/dL in the third trimester. However, urine volume gradually decreased to less than 100 mL per day. The follow-up data of dry weight, predialysis BUN and Hb level are shown in Fig. 2.

Fetal growth was appropriate for gestational age. Routine fetal karyotyping was performed at 16 gestational weeks, but mutation screening was not performed. At 34.5 weeks of gestation, the membrane ruptured during HD, and vaginal delivery was performed without any complications. She delivered a healthy female weighing 2,100 g. One week after delivery, the patient was hospitalized for 5 days because of postpartum cardiomyopathy.

Previous studies suggested pregnancy in women with ADPKD and normal kidney function can result in a favorable outcome. Milutinovic et al. (3) studied fertility and pregnancy complications between patients with polycystic kidneys (n=76) and a control group (no polycystic kidney) (n=61) of women at risk of ADPKD. They found no significant distinction between the 2 groups with regard to fertility, spontaneous abortion, stillbirth, or urinary tract infection (3). Another study showed that overall fetal complication rates were not significantly different between women with and without ADPKD (4).

On the contrary, affected women with preexisting renal failure and hypertension developed various complications and were associated with poor fetal outcome. Other risk factors for fetal complications include maternal age > 30 yr and development of preeclampsia (4). Landesman and Sherr (5) suggested a classification of pregnant women with ADPKD based on severity of renal disease. The patient in this case would be classified into Group C, which refers to patients in renal failure secondary to advanced PKD. Katz et al. (6) first described a successful pregnancy in a patient with Group C disease, and other cases have also been reported (6-9). However, few of them underwent HD during pregnancy. Prophylactic hemodialysis was needed in 1 case (8), and in another case series, we found a PKD patient who underwent nocturnal HD, which is seldom performed in Korea (10).

With this background, we sought to determine the best way to secure fetal survival and a good maternal outcome. First, the management of CKD-related complications and the HD schedule were reviewed. Pregnant women with a favorable outcome were found to have lower predialysis BUN levels compared to those with adverse fetal outcomes (11). It is recommended to increase the hemodialysis frequency (usually 4-6 sessions/week) to maintain a predialysis BUN below 50 mg/dL (12). This provides a less uremic environment for the fetus, allows better control of volume status and BP, and permits the mother a more liberal diet. It also reduces the risk of intradialytic hypotension, which may be associated with fetal distress and premature labor (12). Increasing the dialysis dose prolongs gestation, resulting in higher birth weights and a better chance of fetal survival (13).

Hypertension is the most frequently reported maternal complication in HD patients, occurring in 42%-80% of women (14). Both the rate of fetal survival and birth weights were lower in hypertensive pregnant patients compared to normotensive patients. This indicates that control of BP is especially important in ADPKD patients during pregnancy. Maternal dry weight and interdialytic weight gain should be regularly evaluated and adjusted according to changes in fetal growth (12). Dry weight often needs to be increased to 0.5 kg per week. Anemia should be aggressively corrected using erythropoietin and intravenous iron. A lower third trimester hematocrit was associated with risk of an adverse fetal outcome and low birth weight (11). Erythropoietin dose needs to be increased by approximately 50% in order to maintain a target hemoglobin level of 10-11 g/dL (13).

Another important area of concern for ADPKD patients is the mass effect of huge kidneys and/or a massive polycystic liver. This can cause chronic pain and compression of adjacent organs, resulting in indigestion, gastroesophageal reflux, malnutrition, and ascites (compression of IVC or portal vein). Although ADPKD does not affect fertility, pregnancy in patients with large kidneys at an advanced stage of renal failure has not been reported. The patient in this case had a measured kidney volume of about 6 L which is 30-fold larger than normal. Therefore, we were concerned about a potentially inadequate space for fetal growth. Fortunately, the patient's liver size was normal with only a few small cysts, and she had no symptoms related to a mass effect. Moreover, abdominal muscles during pregnancy can adapt to increased space requirements by increasing the intra-abdominal volume under the influence of various hormones, such as relaxin. This case illustrates that even a very large kidney volume has no significant adverse effect on pregnancy.

Lastly, the risk of congenital anomalies and inheritance of mutant PKD genes should be evaluated. Prenatal genetic diagnosis can be offered by obtaining fetal DNA through chorionic villus sampling or amniocentesis. However, demand for prenatal diagnosis for elective abortion seems to be low, as in our case, and only 4% of women with ADPKD would terminate a pregnancy if they knew the inheritance status (15).

Although pregnancy remains risky in ADPKD patients with ESRD undergoing long-term hemodialysis, outcomes can be improved by optimizing management through a multidisciplinary team of nephrologists, obstetricians, and neonatal care specialists. Intensified dialysis, proper anemia management, and improved obstetric monitoring and neonatal care are likely to contribute to increased infant survival. Medical surveillance and detailed planning for maternal and fetal care are strongly recommended. Preconception counseling is needed in all women on dialysis because most of the pregnancies reported were unplanned.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Piccoli GB, Conijn A, Consiglio V, Vasario E, Attini R, Deagostini MC, Bontempo S, Todros T. Pregnancy in dialysis patients: is the evidence strong enough to lead us to change our counseling policy? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010; 5:62–71.

2. Wilson PD. Polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2004; 350:151–164.

3. Milutinovic J, Fialkow PJ, Agodoa LY, Phillips LA, Bryant JI. Fertility and pregnancy complications in women with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Obstet Gynecol. 1983; 61:566–570.

4. Chapman AB, Johnson AM, Gabow PA. Pregnancy outcome and its relationship to progression of renal failure in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1994; 5:1178–1185.

5. Landesman R, Scherr L. Congenital polycystic kidney disease in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1956; 8:673–680.

6. Katz M, Quagliorello J, Young BK. Severe polycystic kidney disease in pregnancy: report of fetal survival. Obstet Gynecol. 1979; 53:119–124.

7. Mohteshamzadeh M, Coutinho A, Erekosima I, Rustom R, Wong CF. Successful pregnancy in a patient with Landesman's Group C autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol. 2008; 4:227–231.

8. Alcalay M, Blau A, Barkai G, Lipitz S, Mashiach S, Eliahou HE. Successful pregnancy in a patient with polycystic kidney disease and advanced renal failure: the use of prophylactic dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 1992; 19:382–384.

9. Hassan K, Weissmam I, Osman S, Gery R, Oettinger M, Shasha SM, Kristal B. Successful pregnancy in a patient with polycystic kidney disease and advanced renal failure without prophylactic dialysis. Nephron. 2001; 87:85–88.

10. Barua M, Hladunewich M, Keunen J, Pierratos A, McFarlane P, Sood M, Chan CT. Successful pregnancies on nocturnal home hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008; 3:392–396.

11. Luders C, Castro MC, Titan SM, De Castro I, Elias RM, Abensur H, Romão JE Jr. Obstetric outcome in pregnant women on long-term dialysis: a case series. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010; 56:77–85.

12. Giatras I, Levy DP, Malone FD, Carlson JA, Jungers P. Pregnancy during dialysis: case report and management guidelines. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1998; 13:3266–3272.

13. Holley JL, Reddy SS. Pregnancy in dialysis patients: a review of outcomes, complications, and management. Semin Dial. 2003; 16:384–388.

14. Hou S. Pregnancy in chronic renal insufficiency and end-stage renal disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 1999; 33:235–252.

15. Sujansky E, Kreutzer SB, Johnson AM, Lezotte DC, Schrier RW, Gabow PA. Attitudes of at-risk and affected individuals regarding presymptomatic testing for autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Am J Med Genet. 1990; 35:510–515.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download