Abstract

Essential tremor (ET) is one of the most common movement disorders. The prevalence of ET varies substantially among studies. In Korea, there is no well-designed epidemiological study of the prevalence of ET. Thus, we investigated the prevalence of ET in a community in Korea. Standardized interviews and in-person neurological examinations were performed in a random sample of the elderly aged 65 yr or older. Next, movement specialists attempted to diagnose ET clinically. People who showed equivocal parkinsonian features underwent dopamine transporter imaging using [123I]-FP-CIT SPECT, to differentiate ET from parkinsonism. A total of 714 subjects participated in this population-based study. Twenty six of these subjects were diagnosed as having ET. The crude prevalence of ET was 3.64 per 100 persons. Age, gender, or education period were not different between the ET patients and the non-ET subjects. The prevalence of ET was slightly lower than those reported in previous studies. Further studies including more subjects are warranted.

Essential tremor (ET), characterized by action tremors, is the most common type of movement disorder (1). In the past, ET was not considered to be a primary health concern. However, visible tremor can be a bothersome issue with regard to one's social life. Furthermore, ET can be considered to be a physical handicap among elderly subjects. Therefore, many patients visit clinics to have ET treated and to receive an accurate diagnosis of their tremor. The pathogenesis of ET has yet to be elucidated clearly, and many types of tremor mimic ET and are manifested in other neurological disorders, such as Parkinson's disease (PD) and drug-induced tremors. ET has bimodal peaks in connection with age at onset (2); the first peak is in late adolescence to early adulthood, and the second is in older adulthood. The prevalence of ET increases with age and becomes prominent after the age of 60 yr (3, 4). Estimates of the prevalence of ET vary substantially depending on the study (1). In Korea, there is no report of the prevalence of ET proved from well-designed epidemiological studies. In this study, we investigated the prevalence of ET in a community in Korea.

This study was a part of the Korean Longitudinal Study on Health and Aging (KLoSHA), which is a population-based, prospective cohort study of elderly persons aged ≥65 yr in Korea (5). Subject collection for the KLoSHA was conducted between September of 2005 and August of 2006 among the residents of Seongnam City in Korea. Seongnam City is one of the largest satellite cities of Seoul, Korea. The total population of Seongnam City was 931,019 in 2005, and 6.6% of the population was aged 65 yr or older. A simple random sample (N=1,118) was drawn from the roster of 61730 individuals aged 65 yr or older, who were residents of Seongnam on 1 August 2005, using random number generation of SPSS. All of the subjects were ethnic Koreans. The mean age of the 1,118 subjects was 76.3±8.7 yr (range 65-99 yr), and there were 701 men and 417 women. Our study included only non-institutionalized individuals. All of the sampled subjects were invited to participate in the study by letter and telephone. Of the 1,118 subjects, 714 agreed to participate in the baseline study of the KLoSHA (a response rate of 63.9%).

All of the assessments were performed at Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, which is located in Seongnam City, Korea, during 2006 and 2007 after the subject collection step. In the baseline study of the KLoSHA, all participants were evaluated by physicians and nurses with a detailed interview, including a review of their medications, lifestyles and comorbidity rates. To assess general health status, standardized questionnaires included Korean version of the Consortium to establish a registry for Alzheimer's disease assessment packet clinical assessment battery, dementia care assessment packet, 36-item short-form health survey, Baltimore longitudinal study of aging (BLSA) activity questionnaire, the medical outcome study social support survey, nutritional screening initiative, BLSA weight history questionnaire, BLSA activities questionnaire, Canadian study of health and aging community questionnaire, activities-specific balance confidence scale, performance-oriented assessment of mobility problems in elderly patients, functional vision screening questionnaire, hearing handicap inventory for the elderly-short form, Korean activities of daily living scale, Korean instrumental activities of daily living scale, alcohol consumption amount questionnaire, the Fagerstrom test for nicotine dependence (5). Laboratory tests comprised of complete blood count, liver function test, renal panel, lipid panel, coagulation panel, iron panel, serologic test, thyroid function test, urine analysis, and electrocardiography (5). All of the assessments were performed at Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, which is located in Seongnam.

During the initial phase of the present study, subjects were screened using symptom-based questions (See Appendix) (6). The questionnaire was found to be good in predicting parkinsonism. We previously conducted a study of the prevalence of PD using this questionnaire (7). The questionnaire includes an item to identify subjects with tremors: "Have you ever noticed a tremor of your hands, arms, legs or head?" However, this questionnaire was developed for screening PD, and furthermore, there are subjects who do not recognize their own body oscillations (8). To overcome these limitations, physicians conducted neurological examinations of all of the participants, regardless of whether they answered positively or negatively to this item. As the final phase of this study, those who were positive for tremor were examined by a movement disorder specialist, and a clinical diagnosis of ET was made using the ET diagnostic criteria (9). Secondary causes of tremor were ruled out with laboratory tests, in this case the electrolyte panel and thyroid hormone, liver enzyme, serum copper and ceruloplasmin level tests. In addition, medications were checked and cases of drug-induced tremors were excluded. To differentiate from tremor disorders like PD, the subjects with equivocal parkinsonian features, such as reduced facial expressions, resting tremor, and reduced arm swing, underwent dopamine transporter (DAT) imaging, using [123I]-FP-CIT SPECT, to differentiate those features from parkinsonism (7). DAT is located in the presynaptic dopaminergic nerve terminals. In PD, damage to dopaminergic neurons is clearly visualized by reduced uptake of [123I]-FP-CIT, but in ET, DAT images are normal.

The prevalence of ET was calculated and stratified by gender and age (65-69 yr, 70-74 yr, 75-79 yr, and 80 yr old or over). Ninety-five percent confidence intervals (CIs) for each prevalence estimate were derived using exact methods for a binomial parameter. The prevalence estimates were adjusted by age and gender with regard to the population aged 65 and over in the Seongnam City district in order to estimate the overall prevalence rates in the district. Standardized prevalence rates for elderly Koreans were also estimated using a direct standardization method in which the prevalence rates were adjusted by age and gender to the total Korean population, as given in the 2005 national census. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 15.0.

The subjects were fully informed regarding their participation in the study, and written informed consent was obtained from the subjects themselves or from their legal guardians. This study was approved by the institutional review board of Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (IRB No. B-0508/023-003).

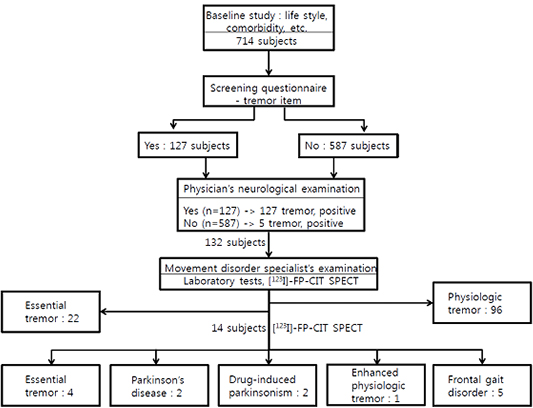

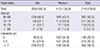

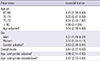

A total of 714 subjects participated in this population-based study (response rate=63.9%). Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the 714 subjects, including their age, gender and education. A total of 127 subjects responded 'yes' to the tremor item on the questionnaire. Among those subjects who responded negatively to this item, the neurological examinations detected five additional subjects with tremors (Fig. 1). In the total of 132 subjects with tremors, 22 subjects were diagnosed as having ET according to the ET diagnostic criteria (9). The five additional subjects found on physician's neurological examination to have previously unnoticeable tremor were diagnosed as ET by visible and persistent postural tremor and its history. In the 132 subjects, 96 subjects were diagnosed as having physiologic tremor because their tremor was transient and not lasting, highly emotion-related, not interfering with activities, and of irregular amplitude and frequency. In the 132 subjects, 14 subjects underwent DAT imaging, [123I]-FP-CIT SPECT, because they showed suspected bradykinesia (11 subjects), a festinating gait in one subject, equivocal rigidity in one subject, and resting tremor in one subject. Twelve of them showed normal DAT density, excluding a diagnosis of PD (7). Among those 12 subjects, four were diagnosed as having ET; three of the four ET patients had suspicious bradykinesia, and the other one had equivocal rigidity. Finally, 26 subjects were diagnosed with ET (M:F=12:14). The four ET subjects confirmed to have normal DAT density underwent a follow-up examination to determine whether suspicious extrapyramidal signs had evolved into overt parkinsonism. After a six-year follow-up, none of them showed overt parkinsonism.

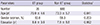

As shown in Table 2, we compared demographic data among the patients with ET (the ET group) and the patients without ET (the non-ET group). Age, gender, and education period did not differ between the ET and non-ET groups. In the population aged less than 80 yr, the prevalence of ET ranged from 3.23 to 4.24, showing similarity between the age categories (Table 3). The overall crude prevalence of ET was 3.64 per 100 persons. The prevalence adjusted to the Seongnam City population and standardized to the Korean population for age and gender was similar to the overall crude prevalence.

In this study, a questionnaire and in-person neurological evaluations were utilized to investigate all possible ET cases, and subjects with equivocal parkinsonian features underwent [123I]-FP-CIT SPECT to reduce the risk of misestimating the prevalence of ET. We found that the overall crude prevalence of ET was 3.64 per 100 persons aged 65 yr or older in a community in Korea. The prevalence standardized to the Korean population was similar to the overall crude prevalence, 3.47 per 100 persons aged 65 yr or older.

The regional variability of the prevalence of ET varies widely. In North American persons aged 65 yr or older, it has been reported that the prevalence of ET is 40.2 per 1,000 (10), or 5.5% (4). In a door-to-door survey performed in Bombay, India, the prevalence of ET was 5049.0 in 100,000 persons aged 70 to 79 and 6919.3 in 100,000 persons aged 80 and over (11). In a door-to-door survey done in the Bidasoa region of Spain, the age-adjusted prevalence in people 65 yr or older was found to be 4.8 per 100 persons (12). The prevalence of ET reported from Mersin, Turkey, was 4.0% in persons aged more than 40 yr (13). The crude prevalence of ET in our study, 3.64 per 100 persons aged 65 yr or older, is slightly lower than the rates in other studies. Factors that cause this variability may include differences in the characteristics of populations, such as ethnic and age differences; different diagnostic criteria, study designs, and sample sizes; a low sensitivity level of screening questionnaires; and the fact that some tests were done by non-specialized examiners. Studies performed in Israel and Singapore reported much lower prevalence rates. In the Northern District of Israel, the prevalence rates of ET and PD were investigated in 900 persons aged 65 yr or older (14). The prevalence of ET was 0.78 per 100 persons, while that of PD was 1.44. The authors suggested that this unusually low ET prevalence may stem from methodological variations. In a community-based survey conducted in Singapore, the prevalence rate of ET was 2.37 per 1,000 in persons aged 50 yr and above (15). An increased prevalence of ET with advancing age has been reported (3, 4, 10, 16). In our study, ET prevalence did not show an increase in persons aged over 80 yr. This discrepancy can be attributed to the small number of subjects aged more than 80 yr. A significant number of the persons of an advanced age live in an institution, and this factor may have prevented very old individuals from participating in this study. Further studies including more subjects of an advanced age are therefore needed.

Together with regional variability, ethnic differences are also found to be related to the prevalence of ET. In the United States, the prevalence of ET was found to be 1.7% in Caucasians and 0.4% in African Americans in persons aged 65 yr or over from four communities (17). In Northern Manhattan in New York, the prevalence of ET was 3.1% in non-Hispanic whites, 5.9% in non-Hispanic African Americans, and 7.3% in Hispanics (4). The variable prevalence rates in ethnic groups in the same region suggest a susceptible genotype existing in each ethnic group. Risk gene variants that cause ET have in fact been reported (18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23). Although the present study investigated only the prevalence of ET in one ethnic group in Korea, further studies could begin here with the goal of elucidating the genetic causes of ET in the Korean population.

Our study reported the prevalence of ET in Seongnam City, Korea. We attempted to improve the diagnostic accuracy of the study using a questionnaire and in-person neurological examinations of all participants, along with [123I]-FP-CIT SPECT. The crude prevalence of ET was 3.64 per 100 persons, which was slightly lower than the rates found in previous studies. Limitations of our study include a small sample size, especially with regard to the oldest age category. Further studies including more subjects are thus warranted.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Flow chart showing the study process and results. In the 132 subjects in total with tremor, 14 subjects underwent [123I]-FP-CIT SPECT. Twelve of them showed normal dopamine transporter density. Among them, four subjects were diagnosed as ET. The others were diagnosed as having drug-induced parkinsonism (n=2), enhanced physiologic tremor due to hyperthyroidism (n=1), and frontal gait disorder (n=5).

Notes

Appendix

Appendix

Questionnaire for the detection of tremor and parkinsonism (reference 6)

(1) Have you noticed that you become more clumsy or have more difficulty with tasks that involve fine hand control: for example, doing up your buttons, using a screwdriver, but not caused by rheumatism, arthritis, or strokes?

(2) Has your handwriting changed and become smaller compared to when you were young?

(3) Do you feel you move more slowly or stiffly?

(4) Do you walk with a stooped posture?

(5) Have you noticed that you don't swing your arms when you walk as much as you used to?

(6) Do you find it difficult to start walking from a standstill or have difficulty in stopping suddenly when you want to?

(7) Have you noticed a tremor of your hands, arms, legs, or head?

(8) Do you have a lack of facial expressions or tend to drool with your mouth half-open?

(9) Have you noticed that your voice has become softer or more monotonous?

(10) When you turn, do you lose balance or do you need to take quite a few steps to turn right around?

(11) After you sit down, do you find it difficult to get up again?

References

1. Louis ED. Essential tremor. Lancet Neurol. 2005; 4:100–110.

2. Louis ED, Dogu O. Does age of onset in essential tremor have a bimodal distribution? Data from a tertiary referral setting and a population-based study. Neuroepidemiology. 2007; 29:208–212.

3. Das SK, Banerjee TK, Roy T, Raut DK, Chaudhuri A, Hazra A. Prevalence of essential tremor in the city of Kolkata, India: a house-to-house survey. Eur J Neurol. 2009; 16:801–807.

4. Louis ED, Thawani SP, Andrews HF. Prevalence of essential tremor in a multiethnic, community-based study in northern Manhattan, New York, N.Y. Neuroepidemiology. 2009; 32:208–214.

5. Park JH, Lim S, Lim JY, Kim KI, Han MK, Yoon IY, Kim JM, Chang YS, Chang CB, Chin HJ, et al. An overview of the Korean longitudinal study on health and aging. Psychiatry Investig. 2007; 4:84.

6. Chan DK, Hung WT, Wong A, Hu E, Beran RG. Validating a screening questionnaire for parkinsonism in Australia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000; 69:117–120.

7. Kim JM, Kim JS, Kim KW, Lee SB, Park JH, Lee JJ, Kim YK, Kim SE, Jeon BS. Study of the prevalence of Parkinson's disease using dopamine transporter imaging. Neurol Res. 2010; 32:845–851.

8. Louis ED, Rios E. Embarrassment in essential tremor: prevalence, clinical correlates and therapeutic implications. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2009; 15:535–538.

9. Brin MF, Koller W. Epidemiology and genetics of essential tremor. Mov Disord. 1998; 13:55–63.

10. Louis ED, Marder K, Cote L, Pullman S, Ford B, Wilder D, Tang MX, Lantigua R, Gurland B, Mayeux R. Differences in the prevalence of essential tremor among elderly African Americans, whites, and Hispanics in northern Manhattan, NY. Arch Neurol. 1995; 52:1201–1205.

11. Bharucha NE, Bharucha EP, Bharucha AE, Bhise AV, Schoenberg BS. Prevalence of essential tremor in the Parsi community of Bombay, India. Arch Neurol. 1988; 45:907–908.

12. Bergareche A, De La, López De, Sarasqueta C, De Arce A, Poza JJ, Martí-Massó JF. Prevalence of essential tremor: a door-to-door survey in bidasoa, spain. Neuroepidemiology. 2001; 20:125–128.

13. Dogu O, Sevim S, Camdeviren H, Sasmaz T, Bugdayci R, Aral M, Kaleagasi H, Un S, Louis ED. Prevalence of essential tremor: door-to-door neurologic exams in Mersin Province, Turkey. Neurology. 2003; 61:1804–1806.

14. Glik A, Masarwa M, Abuful A, Deeb A, Strugatsky R, Farrer LA, Friedland RP, Inzelberg R. Essential tremor might be less frequent than Parkinson's disease in North Israel Arab villages. Mov Disord. 2009; 24:119–122.

15. Tan LC, Venketasubramanian N, Ramasamy V, Gao W, Saw SM. Prevalence of essential tremor in Singapore: a study on three races in an Asian country. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2005; 11:233–239.

16. Benito-León J, Bermejo-Pareja F, Morales JM, Vega S, Molina JA. Prevalence of essential tremor in three elderly populations of central Spain. Mov Disord. 2003; 18:389–394.

17. Louis ED, Fried LP, Fitzpatrick AL, Longstreth WT Jr, Newman AB. Regional and racial differences in the prevalence of physician-diagnosed essential tremor in the United States. Mov Disord. 2003; 18:1035–1040.

18. Deng H, Le W, Jankovic J. Genetics of essential tremor. Brain. 2007; 130:1456–1464.

19. Clark LN, Park N, Kisselev S, Rios E, Lee JH, Louis ED. Replication of the LINGO1 gene association with essential tremor in a North American population. Eur J Hum Genet. 2010; 18:838–843.

20. Tan EK, Teo YY, Prakash KM, Li R, Lim HQ, Angeles D, Tan LC, Au WL, Yih Y, Zhao Y. LINGO1 variant increases risk of familial essential tremor. Neurology. 2009; 73:1161–1162.

21. Wu YW, Prakash KM, Rong TY, Li HH, Xiao Q, Tan LC, Au WL, Ding JQ, Chen SD, Tan EK. Lingo2 variants associated with essential tremor and Parkinson's disease. Hum Genet. 2011; 129:611–615.

22. Tan EK, Foo JN, Tan L, Au WL, Prakash KM, Ng E, Ikram MK, Wong TY, Liu JJ, Zhao Y. SLC1A2 variant associated with essential tremor but not Parkinson disease in Chinese subjects. Neurology. 2013; 80:1618–1619.

23. Wu YR, Foo JN, Tan LC, Chen CM, Prakash KM, Chen YC, Bei JX, Au WL, Chang CW, Wong TY, et al. Identification of a novel risk variant in the FUS gene in essential tremor. Neurology. 2013; 81:541–544.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download