Abstract

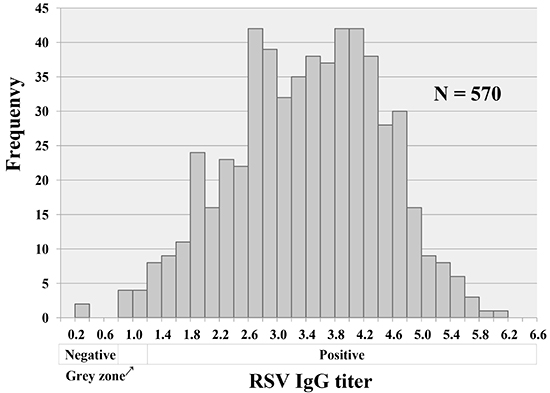

This investigation enrolled 570 healthy young males gathered from all over the country for military service at the Republic of Korea Air Force boot camp. It confirmed RSV IgG seroprevalence by utilizing the enzyme immunoassay method just prior to undergoing basic training. The mean age of this study was 20.25±1.34 yr old. The results of their immunoassay seroprofiles showed that 561 men (98.4%) were positive, 2 (0.4%) were negative and 7 (1.2%) were equivocal belonging to the grey zone. It was confirmed that RSV is a common respiratory virus and RSV infection was encountered by almost all people before reaching adulthood in Korea. Nine basic trainees belonging to the RSV IgG negative and equivocal grey zone categories were prospectively observed for any particular vulnerability to respiratory infection during the training period of two months. However, these nine men completed their basic training without developing any specific respiratory illness.

Respiratory infections in the military service are the most common inflictions in the military healthcare area, yet they are problems not easy to unravel. They may cause death to military personnel often through complications, such as pneumonia and meningitis. Such events could induce a setback in the military schedule affecting military capability and sustaining an enormous loss. Immunity is easily compromised in an ambience of high physical and psychological stress, as well as the dense population of the military training camp. They cause numerous respiratory infections. The results of studies conducted up to now revealed that primary etiologic pathogens included adenoviruses, influenza A and B viruses, Epstein-Barr virus, coronavirus, and rhinoviruses, as well as Streptococcus pneumoniae, Streptococcus pyogenes, Chlamydia pneumoniae and Mycoplasma pneumoniae (1). Recent studies revealed that respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) would also be a significant pathogen that causes respiratory infection and an outbreak of febrile illness in the military (2, 3).

RSV belongs to the family of Paramyxoviridae, and is classified in the genus Pneumovirus. RSV is the most common cause of fatal acute respiratory tract infection in infants and young children. RSV infects virtually everyone by 4 yr of age, and reinfection occurs throughout life, even among the elderly (4, 5, 6). Adults infected with RSV tend to have more variable and less distinctive clinical findings than children, and the viral cause of the infection is often unsuspected (7). This study attempted to verify the seroprevalence of RSV IgG among healthy young adults in their early twenties who had just been admitted to the Korea Air Force basic training camp. Subjects with an RSV IgG seronegative outcome were prospectively observed for vulnerability to respiratory infection, especially during the period of basic training.

Military recruits admitted to the Air Force boot camp were required to undergo a basic health examination which includes a blood sampling test. In this investigation, RSV IgG immunoassay was added to the basic blood test. All subjects were admitted to the training camp on June 26, 2012. They underwent a blood test on June 27, 2012, which was a day after resting without training on the day of admission. The total number of recruits was 570 and all of them underwent an RSV IgG test. After taking samples from RSV IgG tests, these samples were immediately transferred to the Seoul Clinical Laboratories & Seoul Medical Science Institute under a refrigerated state for analysis. With respect to enzymatic immunoassay, an RSV diagnostic reagent (IBL, Hamburg, Germany) was used for the verification of diagnosis. This study was approved by the Medical Research Institutional Review Boards of the Ministry of National Defense (IRB No. AFMC-12-IRB-014). Air Force physicians themselves explained the purpose, method and precautions of this study, and tests were conducted after obtaining an informed consent from each subject.

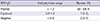

The mean age of subjects was 20.25±1.34 yr old with a range of 18.5-28.0 yr old. The immunoassay seroprofiles showed that 561 men (98.4%) were positive, 2 (0.4%) were negative, and 7 (1.2%) were equivocal belonging to the grey zone (Table 1, Fig. 1). With the exception of 7 recruits in the grey zone, seropositive subjects were 99.6% (561/563). There were no significant differences in RSV IgG titer among variables such as their hometown, size of city or age (P>0.1; ANOVA; SPSS ver. 15.0, Chicago, IL, USA). Nine basic trainees belonging to the RSV IgG negative or equivocal grey zone categories were prospectively observed. Any particular vulnerability to respiratory infection was confirmed by checking their visits to the military medical clinic for two months during the training period. However, all of these nine recruits did not utilize the military medical facilities during the basic training period of two months.

The result of this study showed that the RSV IgG seropositivity of subjects in their twenties was 99.6%. It is difficult to compare the result directly because there exist the different methods or kit for detection of antibody and the criteria of each method. However, such result of seropositivity was similar to that of the US. military personnel, which was 97.8% (8). Even in several previous studies, all children older than 5 yr old were known to have experienced an RSV infection (9, 10). This investigation also confirmed that almost all healthy young military recruits in their early twenties were RSV IgG positive in the Republic of Korea. In an effort to verify the increased vulnerability to respiratory infection for the RSV IgG negative or equivocal grey zone recruits during the training period, the medical records for all 570 subjects were verified in the basic training camp. However, the numbers of trainees with a seronegative result were small while there were totally no records of their utilization of medical facilities for symptoms relating to any respiratory infection, making a statistical analysis impossible. In the meanwhile, the outcome of not experiencing any particular respiratory infection for nine trainees with an RSV IgG negative or an equivocal result during the training period of two months can lead to a notion that young adults with an RSV IgG negative result may not be a risk factor for a respiratory infection in a collective group environment. Nevertheless, such deduction would require further studies for verifications in the days ahead. Immunity to RSV is incomplete, protective immunity against RSV infection is complex and the importance of serum antibody is controversial (11, 12, 13). A study targeting on infants demonstrates that RSV specific maternal IgG has a protective effect against severe infections. Nevertheless, such studies on adult groups are inadequate (14, 15). Although there does not appear to be a defect in humoral immunity, there is evidence that the CD8+ T-cell immunity may be impaired with age (15). Deficient RSV F-specific T-cell responses contribute to susceptibility to severe RSV disease in elderly adults (16).

The significance of this study is the aspect that seroprevalence of RSV IgG of healthy young adults in the Republic of Korea was verified for the first time. The greatest merit of this study is the fact that the subjects were collectively gathered together from all over the country at the same time and may represent healthy young male adults in the Republic of Korea. RSV infections occur primarily in seasonal epidemic. RSV infection occurred predominantly in the fall and winter in the Republic of Korea (6, 17). Therefore, our data is limited. However, as seen from the results of previous studies overseas, it was confirmed that RSV is a common respiratory virus and RSV infection was encountered by almost all people before reaching adulthood in Korea. It is very important to accumulate the basic sero-epidemiological data of every infectious agent. It is anticipated that this study may provide the basic data for RSV related studies in the Republic of Korea in the future. Frequently, an RSV infection in the military may be unsuspected. Nevertheless, RSV is a common cause of respiratory illness and often causes outbreaks in particular adult groups (18, 19). In an effort to prevent respiratory infections in the military, further RSV studies and challenges regarding diagnosis of RSV infection would be necessary.

Figures and Tables

Notes

References

1. Gray GC, Callahan JD, Hawksworth AW, Fisher CA, Gaydos JC. Respiratory diseases among U.S. military personnel: countering emerging threats. Emerg Infect Dis. 1999; 5:379–385.

2. O'Shea MK, Pipkin C, Cane PA, Gray GC. Respiratory syncytial virus: an important cause of acute respiratory illness among young adults undergoing military training. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2007; 1:193–197.

3. O'Shea MK, Ryan MA, Hawksworth AW, Alsip BJ, Gray GC. Symptomatic respiratory syncytial virus infection in previously healthy young adults living in a crowded military environment. Clin Infect Dis. 2005; 41:311–317.

4. Murray PR, Rosenthal KS, Kobayashi GS, Pfaller MA, editors. Medical microvirology. 4th ed. St. Louis: Mosby;2002.

5. Kim JK, Jeon JS, Kim JW, Rheem I. Epidemiology of respiratory viral infection using multiplex rt-PCR in Cheonan, Korea (2006-2010). J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013; 23:267–273.

6. Kim CK, Choi J, Callaway Z, Kim HB, Chung JY, Koh YY, Shin BM. Clinical and epidemiological comparison of human metapneumovirus and respiratory syncytial virus in seoul, Korea, 2003-2008. J Korean Med Sci. 2010; 25:342–347.

7. Hall CB. Respiratory syncytial virus and parainfluenza virus. N Engl J Med. 2001; 344:1917–1928.

8. Eick AA, Faix DJ, Tobler SK, Nevin RL, Lindler LE, Hu Z, Sanchez JL, MacIntosh VH, Russell KL, Gaydos JC. Serosurvey of bacterial and viral respiratory pathogens among deployed U.S. service members. Am J Prev Med. 2011; 41:573–580.

9. Bhattarakosol P, Pancharoen C, Mungmee V, Thammaborvorn R, Semboonlor L. Seroprevalence of anti-RSV IgG in Thai children aged 6 months to 5 years. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2003; 21:269–271.

10. Lu G, Gonzalez R, Guo L, Wu C, Wu J, Vernet G, Paranhos-Baccalà G, Wang J, Hung T. Large-scale seroprevalence analysis of human metapneumovirus and human respiratory syncytial virus infections in Beijing, China. Virol J. 2011; 8:62.

11. Anderson LJ, Heilman CA. Protective and disease-enhancing immune responses to respiratory syncytial virus. J Infect Dis. 1995; 171:1–7.

12. Falsey AR, Walsh EE. Relationship of serum antibody to risk of respiratory syncytial virus infection in elderly adults. J Infect Dis. 1998; 177:463–466.

13. Luchsinger V, Piedra PA, Ruiz M, Zunino E, Martínez MA, Machado C, Fasce R, Ulloa MT, Fink MC, Lara P, et al. Role of neutralizing antibodies in adults with community-acquired pneumonia by respiratory syncytial virus. Clin Infect Dis. 2012; 54:905–912.

14. Ochola R, Sande C, Fegan G, Scott PD, Medley GF, Cane PA, Nokes DJ. The level and duration of RSV-specific maternal IgG in infants in Kilifi Kenya. PLoS One. 2009; 4:e8088.

15. Roca A, Abacassamo F, Loscertales MP, Quintó L, Gómez-Olivé X, Fenwick F, Saiz JC, Toms G, Alonso PL. Prevalence of respiratory syncytial virus IgG antibodies in infants living in a rural area of Mozambique. J Med Virol. 2002; 67:616–623.

16. Cherukuri A, Patton K, Gasser RA Jr, Zuo F, Woo J, Esser MT, Tang RS. Adults 65 years old and older have reduced numbers of functional memory T cells to respiratory syncytial virus fusion protein. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2013; 20:239–247.

17. Ham H, Jang J, Choi S, Oh S, Jo S, Choi S, Pak S. Epidemiological characterization of respiratory viruses detected from acute respiratory patients in Seoul. Ann Clin Microbiol. 2013; 16:188–195.

18. Walsh EE, Falsey AR. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in adult populations. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2012; 12:98–102.

19. Mehta J, Walsh EE, Mahadevia PJ, Falsey AR. Risk factors for respiratory syncytial virus illness among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. COPD. 2013; 10:293–299.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download