Abstract

To identify the correlation between the number of gastric biopsy samples and the positive rate, we compared the results of urease test using one and three biopsy samples from each 255 children who underwent gastroduodenoscopy at Gyeongsang National University Hospital. The children were divided into three age groups: 0-4, 5-9, and 10-15 yr. The gastric endoscopic biopsies were subjected to the urease test. That is, one and three gastric antral biopsy samples were collected from the same child. The results of urease test were classified into three grades: Grade 0 (no change), 1 (6-24 hr), 2 (1-6 hr), and 3 (<1 hr). The positive rate of urease test was increased by the age with no respect to the number of gastric biopsy samples (one biopsy P = 0.001, three biopsy P < 0.001). The positive rate of the urease test was higher on three biopsy samples as compared with one biopsy sample (P < 0.001). The difference between one and three biopsy samples was higher in the children aged 0-9 yr. Our results indicate that the urease test might be a more accurate diagnostic modality when it is performed on three or more biopsy samples in children.

Most cases of Helicobacter pylori infection occur in children (1). There are no differences in diagnostic approaches for H. pylori infection between children and adults. The urease test is a simple, easy, inexpensive diagnostic modality where there is no need for special technique. The rapid urease test is a widely used method with a high sensitivity of 70%-90% in adults (2). However, its sensitivity is relatively lower in children as compared with adults (3, 4). This can be explained by a lower H. pylori density in the gastric sample in children as compared with adolescents or adults (5). It has been reported that the sensitivity of the rapid urease test and the time to positive reaction are improved with the increased number of biopsy samples in adults (6).

Given the above background, we conducted this study to identify the correlation between the number of gastric biopsy samples and the positive rate. In addition, we also examined whether the degree of the above correlation is also associated with the age and the time to positive reaction.

In the current study, we evaluated a total of 255 children who underwent upper gastrointestinal endoscopy at our medical institution. We retrospectively reviewed the charts and the histopathologic slides of the children, but did not analyze a past history of medications (e.g., proton pump inhibitors or antibiotics). Exclusion criteria for the current study include active gastrointestinal bleeding, ingestion of toxic materials, emergency endoscopy, a past history of H. pylori treatment, or poor medical condition.

The children were divided into three age groups: the Group I (0-4 yr) (n=52), the Group II (5-9 yr) (n=125) and the Group III (10-15 yr) (n=78). The gastric endoscopic biopsies were subjected to the urease test. That is, one and three gastric antral biopsy samples were collected from the same child and then incubated in 1.5 mL safe-lock microcentrifuge tube containing 0.3% urea broth (urea 20 g/L, phenol red 0.04 g/L, KH2PO4 0.2 g/L and NaCl 0.5 g/L, pH=6.8). Then, the positive reaction based on the color change was examined over a 24-hr period. Thus, based on the time to positive reaction, the children were classified into three grades: Grade 0 (no color change), 1 (6-24 hr), 2 (1-6 hr) and 3 (< 1 hr). Statistical analysis was done using SPSS 18.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). We examined whether the urease test had a significant correlation with the number of biopsy samples and the age. Using bivariate correlations (Spearman's rho), paired samples t-test and nonparametric tests (Wilcoxon sum rank test and McNemar test), we analyzed the difference in the time to positive reaction between one and three biopsy samples. A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

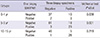

Baseline and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The most common indication for upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was upper abdominal pain/heart burn. This is followed by vomiting, anemia, irritability, poor weight gain, gastrointestinal bleeding and Henoch-Schonlein purpura in the decreasing order.

Histopathologic evaluations were performed on 255 children. The proportion of the children with moderate-to-severe chronic gastritis was increased with age; it was 12.9% in the Group I and 43.6% in the Group III. Moreover, the proportion of the children with active gastritis or H. pylori infiltration was also increased with age. There was a positive correlation between the severity of H. pylori infections and the age (Spearman's rho R=0.242-0.370, P < 0.001). In addition, the severity of chronic gastritis, active gastritis and H. pylori infiltration had a significant positive correlation with the positive rate of urease test (Spearman's rho=0.573-0.814, P < 0.001). There was a positive correlation between the severity of H. pylori infections and the time to positive reaction in all the age groups (P < 0.001).

The positive rate of urease test was increased with the age with no respect to the number of gastric biopsy samples (one biopsy P = 0.001, three biopsy P < 0.001, chi-square test, Fig. 1). The positive rate of the urease test was higher on three biopsy samples as compared with one biopsy sample (P < 0.001) (Fig. 1). On urease test of one biopsy sample, the proportion of the children corresponding to Grade 1, 2, and 3 was 5.8%, 0%, and 3.8%, respectively, in the Group I, 11.2%, 2.4%, and 7.2% in the Group II and 5.1%, 1.3%, and 28.2% in the Group III. On urease test of three biopsy samples, it was 21.2%, 0%, and 3.8% in the Group I; 20.0%, 3.2%, and 9.6% in the Group II; and 6.4%, 2.6%, and 30.8% in the Group III.

The degree of the difference in the positive rate of urease test between one and three biopsy samples was significantly higher in the Group I (P = 0.021) and the Group II (P = 0.001) as compared with the Group III (P = 0.102) (Fig. 1). The time to positive reaction was significantly different from in the Group I (P = 0.001) and II (P < 0.001) to in the Group III (P = 0.029) (Fig. 2). The degree of the correlation between the cumulative positive rate and the incubation time was higher on three biopsy samples as compared with one biopsy sample. Of note, the proportion of the children corresponding to Grade 1 was higher as compared with that of those corresponding to Grade 2 or 3. There was no significant difference in the proportion of the children corresponding to Grade 2 or 3 between one and three biopsy samples in all the age groups.

Of the 197 children, 33 (16.8%) with negative results on one biopsy sample but they showed positive results on three biopsy samples (Table 2). There were no differences in the results of urease test between one and three biopsy samples in the Group III (P = 0.219). In addition, there were six children (10.3%) with negative results on three biopsy samples (Table 2). The proportion of the children with negative results on three biopsy samples was higher in the Group I as compared with the Group II and III.

According to several studies, the accuracy of a diagnosis of H. pylori infection on biopsy can be increased with the increased number of gastric biopsy samples in adults (6-9). In the current study, we reported that the positive rate of urease test was higher on antral and body biopsy samples as compared with antral one in the children (10). This is the first attempt to compare the positive rate and time to positive reaction between one and three biopsy samples in the same children. Our results showed that the positive rate of urease test was higher on three biopsy samples as compared with one biopsy sample in the children aged 0-9 yr. In the children aged 10-15 yr, however, there was no difference in the time to positive reaction between one and three biopsy samples.

The accuracy of the urease test primarily depends on the H. pylori density in the gastric sample, which is generally lower in children as compared with adolescents and adults (5). In children, a low degree of H. pylori colonization and a patchy distribution of the organism in the gastric mucosa could be attributed to sampling errors (5, 11). Our results showed that the severity of active gastritis, the density of H. pylori in the antrum and the positive rate were increased with the age. There was a poor correlation between the inflammatory changes in gastric antrum and the density of H. pylori in the antrum in children with H. pylori infections (12). The degree of the difference in the urease test between one and three biopsy samples was higher in children aged 10 yr or younger as compared with those aged 10-15 yr, which is due to the difference in the proportion of the children with positive color changes for 6-24 hr. These results indicate not only that most cases of H. pylori infection occur during early childhood but also that its density is increased with the age.

With the increased number of gastric biopsy samples on urease test such as CLOtest (Campylobacter-like organism test), the time to positive reaction can be shortened; this is a clinical benefit in adults (6). In more detail, on the CLOtest of four biopsy samples, the time to positive reaction was shorter than 1 hr with a positive rate of 100%. On the CLOtest of one, two or three biopsy samples, however, it was also shorter than 1 hr but the positive rate was 8%, 18% or 53%, respectively. In the current study, however, there was no significant difference in the proportion of the children with time to positive reaction of < 6 hr with no respect to the number of biopsy samples. This indicates that there was no correlation between the density of H. plylori and the number of gastric biopsy samples in all the age groups. Presumably, this might be due to that the density of H. pylori is lower and its distribution is more patchy in children as compared with adults.

There are several limitations of the current study as follows: 1) We compared the results of urease test between one and three biopsy samples. However, we failed to compare between two biopsy samples and 1-3 ones. 2) A diagnosis of H. pylori was made on H&E-stained histopathologic samples. However, there was no difference in the sensitivity for detecting H. pylori between the H&E and Giemsa stains (13). 3) We conducted the current study under retrospective design. We simply analyzed the results of the urease tests and histopathologic findings. However, we failed to evaluate clinical history except for chief complaints. We could not clarify the reasons for false-negative results of urease test. It is generally known that false-negative results of urease test are associated with the use of acid suppression medications such as PPI, bleeding and a very low density of H. pylori (14, 15). Moreover, they are also associated with sampling errors due to a patchy distribution of H. pylori in the gastric mucosa (16).

To summarize, our results are as follows: 1) The positive rate and the time to positive reaction had a significant correlation with the number of gastric biopsy samples. 2) The degree of the difference in the positive rate and the time to positive reaction between one and three biopsy samples was higher in the children aged 0-9 yr, although there was no significant difference in the proportion of the children with time to positive reaction of < 1 hr between all the age groups. Presumably, this might be due to a lower density and a more patchy distribution of H. pylori in children.

In conclusion, our results indicate that the urease test might be a more accurate diagnostic modality when it is performed on three or more biopsy samples. Further studies are warranted to determine the accurate time to positive reaction and the exact number of gastric biopsy samples, which is essential for making an accurate diagnosis of H. pylori infection in children.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

The difference in the positive rate of urease test between one and three biopsy samples in all the age groups. The positive rate of urease test was increased with the age with no respect to the number of gastric biopsy samples (one biopsy P = 0.001, three biopsy P < 0.001). The positive rate of the urease test was higher on three biopsy samples as compared with one biopsy sample (P < 0.05). GU1, 32.2%; GU3, 40.1%.

Fig. 2

The cumulative percentage of positive rate depending on the age and the number of biopsy samples. The degree of the correlation between the cumulative positive rate and the incubation time was higher on three biopsy samples as compared with one biopsy sample. GU1, Spearman R = 0.931, P < 0.001; GU3, Spearman R = 0.907, P < 0.001.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The biospecimens used in this study were provided by Gyeongsang National University Hospital, which is a member of the National Biobank of Korea that is funded by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea Government.

Notes

References

1. Malaty HM, El-Kasabany A, Graham DY, Miller CC, Reddy SG, Srinivasan SR, Yamaoka Y, Berenson GS. Age at acquisition of Helicobacter pylori infection: a follow-up study from infancy to adulthood. Lancet. 2002; 359:931–935.

2. Midolo P, Marshall BJ. Accurate diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori: urease tests. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2000; 29:871–878.

3. Dondi E, Rapa A, Boldorini R, Fonio P, Zanetta S, Oderda G. High accuracy of noninvasive tests to diagnose Helicobacter pylori infection in very young children. J Pediatr. 2006; 149:817–821.

4. Madani S, Rabah R, Tolia V. Diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection from antral biopsies in pediatric patients is urease test that reliable? Dig Dis Sci. 2000; 45:1233–1237.

5. Elitsur Y, Hill I, Lichtman SN, Rosenberg AJ. Prospective comparison of rapid urease tests (PyloriTek, CLO test) for the diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection in symptomatic children: a pediatric multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998; 93:217–219.

6. Siddique I, Al-Mekhaizeem K, Alateegi N, Memon A, Hasan F. Diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori: improving the sensitivity of CLOtest by increasing the number of gastric antral biopsies. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008; 42:356–360.

7. Genta RM, Graham DY. Comparison of biopsy sites for the histopathologic diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori: a topographic study of H. pylori density and distribution. Gastrointest Endosc. 1994; 40:342–345.

8. Lim LL, Ho KY, Ho B, Salto-Tellez M. Effect of biopsies on sensitivity and specificity of ultra-rapid urease test for detection of Helicobacter pylori infection: a prospective evaluation. World J Gastroenterol. 2004; 10:1907–1910.

9. Vassallo J, Hale R, Ahluwalia NK. CLO vs histology: optimal numbers and site of gastric biopsies to diagnose Helicobacter pylori. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001; 13:387–390.

10. Seo JH, Youn HS, Park JJ, Yeom JS, Park JS, Jun JS, Lim JY, Park CH, Woo HO, Ko GH, et al. Influencing factors to results of the urease test: age, sampling site, histopathologic findings, and density of Helicobacter pylori. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr. 2013; 16:34–40.

11. Carelli AP, Patrício FR, Kawakami E. Carditis is related to Helicobacter pylori infection in dyspeptic children and adolescents. Dig Liver Dis. 2007; 39:117–121.

12. Drumm B. Helicobacter pylori in the pediatric patient. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1993; 22:169–182.

13. Laine L, Lewin DN, Naritoku W, Cohen H. Prospective comparison of H&E, Giemsa, and Genta stains for the diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997; 45:463–467.

14. Tang JH, Liu NJ, Cheng HT, Lee CS, Chu YY, Sung KF, Lin CH, Tsou YK, Lien JM, Cheng CL. Endoscopic diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection by rapid urease test in bleeding peptic ulcers: a prospective case-control study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009; 43:133–139.

15. Gisbert JP, Abraira V. Accuracy of Helicobacter pylori diagnostic tests in patients with bleeding peptic ulcer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006; 101:848–863.

16. Engstrand L, Rosberg K, Hübinette R, Berglindh T, Rolfsen W, Gustavsson S. Topographic mapping of Helicobacter pylori colonization in long-term-infected pigs. Infect Immun. 1992; 60:653–656.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download