Abstract

Periodontal disease is a predictor of stroke and cognitive impairment. The association between the number of lost teeth (an indicator of periodontal disease) and silent infarcts and cerebral white matter changes on brain CT was investigated in community-dwelling adults without dementia or stroke. Dental examination and CT were performed in 438 stroke- and dementia-free subjects older than 50 yr (mean age, 63 ± 7.9 yr), who were recruited for an early health check-up program as part of the Prevention of Stroke and Dementia (PRESENT) project between 2009 and 2010. In unadjusted analyses, the odds ratio (OR) for silent cerebral infarcts and cerebral white matter changes for subjects with 6-10 and > 10 lost teeth was 2.3 (95% CI, 1.38-4.39; P = 0.006) and 4.2 (95% CI, 1.57-5.64; P < 0.001), respectively, as compared to subjects with 0-5 lost teeth. After adjustment for age, education, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, and smoking, the ORs were 1.7 (95% CI, 1.08-3.69; P = 0.12) and 3.9 (95% CI, 1.27-5.02; P < 0.001), respectively. These findings suggest that severe tooth loss may be a predictor of silent cerebral infarcts and cerebral white matter changes in community-dwelling, stroke- and dementia-free adults.

Tooth loss is known to be associated with Alzheimer disease and dementia (1-5). Suggested underlying mechanisms include nutritional defects due to poor mastication and chronic inflammation due to oral pathogens (3, 6). Some animal studies have suggested that decreased masticatory function due to tooth loss leads to decreased acetylcholine synthesis, which results in learning and memory disorders (7). However, the exact mechanism underlying this phenomenon is not well understood.

Cardiovascular risk factors, such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, and smoking, are known to cause dementia via subclinical vascular brain damage (8). Many neuroimaging studies have suggested the role of white matter degeneration and microbleeds in cognitive impairment (9-11). However, it is currently unknown whether these additional pathologies represent separate pathological substrates for cognitive impairment (12).

Tooth loss is another cerebrovascular risk factor (13-15). Like other cerebrovascular risk factors, tooth loss may be associated with brain white matter change (WMC) or silent infarction (SI). We think that tooth loss may cause dementia via brain WMC/SI much like other cerebrovascular risk factors. If tooth loss causes dementia through brain WMC/SI, WMC/SI may precede dementia. Stewart et al. (16) reported that WMC was correlated with subjective memory defects in a non-dementia community population. The risk of ischemic stroke was negatively correlated with the number of remaining teeth (17). We hypothesized that the risk of WMC/SI in subjects without dementia is correlated with the number of lost teeth. However, a direct association between tooth loss and brain white matter lesions has not been established.

To investigate our hypothesis in a community-based setting, we collected data from the Prevention of Stroke and Dementia (PRESENT) project. The PRESENT project is an ongoing project supported by the regional government that was initiated in July 2007. Its goal is the prevention of stroke and dementia by public education, public relation, early medical check-ups, and research in Ansan City, Gyeonggi-do, Korea.

As a part of the PRESENT project, stroke-free and dementia-free adults (aged 50-75 yr) were recruited by random sampling or volunteering. Data collection involved 2 steps conducted over 2 yr from January 2009 to December 2010. First, systematic random sampling with administrational support from the regional government was performed in 2009. In the baseline cohort (n = 119,359 in 2009), we contacted every 100th person by using a registered list received officially from the regional government office (the PRESENT project is a regional government-run project). A telephone interview was conducted by a trained nurse. If a potential participant could not be contacted, refused to participate, had moved, or had a history of stroke or dementia, we contacted the next person on the list. We attempted to contact 1,240 people in total, of which 551 people could not be contacted, 366 refused to participate, and 23 had a history of stroke or dementia. In total, 300 participants were selected in the first step. In the second step, 350 subjects without any history of stroke or dementia were selected from volunteers with a low socioeconomic background, or who earned < 200% of the minimum cost of living, and who wanted a health check-up in 2010. All procedures were performed after obtaining written permission from the paticipents.

Personal interviews and evaluations by trained nurses and neurologists were performed. Education, hypertension, smoking, diabetes, and hypercholesterolemia data were recorded. Blood pressure was measured. Blood chemistry was analyzed. Hypertension was defined as a previous diagnosis of hypertension, the use of 1 or more anti-hypertensive drugs, a systolic pressure of ≥ 140 mmHg, or a diastolic pressure of ≥ 90 mmHg (18). Hypercholesterolemia was defined as the use of 1 or more lipid-lowering agents, a fasting total cholesterol level of ≥ 240 mg/dL, a low-density lipoprotein cholesterol level of ≥ 160 mg/dL, or a triglyceride level of ≥ 200 mg/dL (19). A participant was said to have diabetes mellitus if he/she had a previous diagnosis of diabetes mellitus, used anti-diabetic medication (including insulin), or had a fasting glucose level of ≥ 126 mg/dL (20). Smoking was defined as a current smoking habit.

Brain CT was performed, and the obtained results were independently evaluated by 2 neurologists who were blinded to the clinical condition and laboratory assessment of the subjects. Based on the brain CT results, subjects were divided into 2 groups: normal and WMC/SI. The WMC/SI group included participants with WMC, SI, or both WMC and SI. SI was defined as the presence of well-defined areas with diameter greater than 2 mm and showing attenuation without relevant clinical neurologic events, and WMC was defined as the presence of ill-defined and moderately hypodense areas with diameters ≥ 5 mm in the periventricular or subcortical area. This includes extensive periventricular lesion and severe leukoencephalopathy (21, 22).

Dental examination was performed by a dentist at the community health center. The numbers of lost teeth were counted.

Data were analyzed with the χ2 test, t-test, and multiple regression analysis in the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS; Windows version 18, SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). We used multiple regression analysis to obtain odds ratios (ORs) and adjusted ORs. The independent variable was the number of lost teeth. We divided the number of lost teeth into 3 categories, namely, 0-5 teeth; 6-10 teeth; and more than 10 teeth. Well-known risk factors for WMC/SI were used as covariates; these were age, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, education, and current smoking status. Education is not a known risk factor for WMC/SI, but education was found to influence oral health and cognitive function in a community based survey (5); therefore, we included the number of years in education as a covariate. We used 2-tailed P values for all analyses. The P value of significance for our analyses was 0.01.

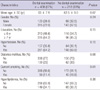

Among the 650 subjects, 438 underwent dental examination by a dentist. However, the baseline characteristics of the subjects who did and did not undergo the dental examination were similar. The baseline characteristics of the subjects are shown in Table 1.

Of the 438 subjects who underwent the dental examination, 318 showed normal brain CT findings, and 120 showed WMC/SI findings on brain CT. Inter-rater concordance rate of brain CT interpretation divided by normal or WMC/SI finding was good (k = 0.89; 91% concordance). Age (≥ 65 yr), incidence of hypertension and diabetes mellitus, and the number of lost teeth were significantly greater in the WMC/SI group than in the normal brain CT group (Table 2). There was no difference in the number of lost teeth when the WMC/SI group was further divided into the WMC only (n = 80, 10.0 ± 12.0), SI only (n = 8, 9.4 ± 9.6), and WMC and SI (n = 32, 9.9 ± 9.1) groups.

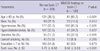

In the unadjusted analysis, the OR of cerebral WMC/SI for subjects with 6-10 lost teeth and more than 10 lost teeth was 2.3 (95% CI, 1.38-4.39; P = 0.006) and 4.2 (95% CI, 1.57-5.64; P < 0.001), respectively, when compared to subjects with 0-5 lost teeth. After adjustment for age, education, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, and smoking, the OR was 1.7 (95% CI, 1.08-3.69; P = 0.12) for patients with 6-10 lost teeth and 3.9 (95% CI, 1.27-5.02; P < 0.001) for patients with more than 10 lost teeth (Fig. 1).

The study population consisted of 2 groups. The first population, recruited in 2009, was a randomly sampled group, and the second population, recruited in 2010, consisted of volunteers. The baseline characteristics of the 2 groups were different (data not shown) in that the age of the volunteer group was higher than that of the first population. Age is a very important factor that influences characteristics such as hypertension. However, we do not think this factor influenced our results. Furthermore, the aim of this study was not to compare the 2 groups. This study was a cohort-based, cross-sectional, observational study, and we thought that it was important to recruit as many participants to the cohort as possible. The 2 groups were selected independently from the same cohort. There was no artificial manipulation in participant selection of the volunteer group, and the study group was randomly chosen.

Periodontitis and dental caries are 2 major causes of tooth loss. Before middle age, the most common reason for tooth loss is caries; however, later in life, periodontitis becomes the major cause of tooth extraction (23). With respect to pathophysiology, periodontitis and subsequent bacteremia cause vascular damage. However, recording tooth loss is much easier than assessing periodontitis directly, and most studies have used the number of lost teeth as a variable reflecting periodontitis (13, 24). Some authors have suggested that caries should perhaps be investigated as a potential independent risk factor for atherosclerosis (25). We believe that the loss of 1-5 teeth may be because of cosmetic problems, wisdom tooth pain, or trauma without the presence of any underlying periodontal disease. Therefore, we used subjects who had lost 0-5 teeth as controls. A large prospective study on tooth loss and incidence of ischemic stroke used a control group of subjects who still had 25 to 32 teeth (a normal adult has 28 to 32 teeth depending on the presence or absence of the wisdom teeth) (17). We did not count the number of remaining teeth (which can be counted easily by a non-dentist), but instead counted the number of lost teeth. All subjects included in this study underwent a dental examination by a dentist.

Age, incidence of hypertension and diabetes mellitus, and the number of lost teeth for the WMC/SI group were significantly greater than those for the normal brain CT group. Compared to the normal brain CT group, the WMC/SI group showed a greater incidence of current smoking and hypercholesterolemia, but this difference was not significant. We believe that this result was not significant because of the small sample size. Except for the results for tooth loss, our results are similar to those of a previous study (11).

To eliminate the effect of other well-known cerebrovascular risk factors, we adjusted the data by using the covariates of age, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, education, and current smoking status. The adjustment of these other risk factors showed that severe tooth loss was associated with a high risk of WMC/SI.

This study was a cross-sectional study and not a large prospective study, and the dependent variable was not stroke or dementia. Nonetheless, the findings of the study are valuable because this is a community-based study for healthy adults without stroke and dementia. The PRESENT health promotion project aimed to prevent stroke and dementia, and therefore, our study population did not include individuals diagnosed with stroke or dementia. A large community-based longitudinal cohort study showed that brain white matter lesions precede the occurrence of stroke and cognitive decline as a risk factor (11).

In conclusion, tooth loss is associated with brain WMC/SI. Furthermore, tooth loss may be a predictor of WMC/SI. Almost all periodontal problems are preventable and treatable conditions. Therefore, we believe that community-based, early life and regular dental care education and campaign programs can decrease the incidence of stroke and dementia. We hope that further studies about the relationship between periodontal disease and brain lesions or cognitive impairments will be planned in the near future.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Odds ratios (OR) of unadjusted (A) and adjusted (B) multivariate analysis. The OR for silent cerebral infarcts and cerebral white matter changes for subjects with 6-10 teeth and >10 lost teeth was 2.3 (95% CI, 1.38-4.39; P < 0.01) and 4.2 (95% CI, 1.57-5.64; P < 0.01), respectively, as compared to subjects with 0-5 lost teeth. After adjustment for age, education, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, and smoking, the OR was 1.7 (95% CI, 1.08-3.69; P = 0.12) for subjects with 6-10 lost teeth and 3.9 (95% CI, 1.27-5.02; P < 0.01) for subjects with >10 lost teeth.

References

1. Kamer AR, Morse DE, Holm-Pedersen P, Mortensen EL, Avlund K. Periodontal inflammation in relation to cognitive function in an older adult Danish population. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012; 28:613–624.

2. Batty GD, Li Q, Huxley R, Zoungas S, Taylor BA, Neal B, de Galan B, Woodward M, Harrap SB, Colagiuri S, et al. Oral disease in relation to future risk of dementia and cognitive decline: prospective cohort study based on the Action in Diabetes and Vascular Disease: Preterax and Diamicron Modified-Release Controlled Evaluation (ADVANCE) Trial. Eur Psychiatry. 2013; 28:49–52.

3. Stein PS, Desrosiers M, Donegan SJ, Yepes JF, Kryscio RJ. Tooth loss, dementia and neuropathology in the Nun Study. J Am Dent Assoc. 2007; 138:1314–1322.

4. Kaye EK, Valencia A, Baba N, Spiro A 3rd, Dietrich T, Garcia RI. Tooth loss and periodontal disease predict poor cognitive function in older men. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010; 58:713–718.

5. Stewart R, Sabbah W, Tsakos G, D'Aiuto F, Watt RG. Oral health and cognitive function in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III). Psychosom Med. 2008; 70:936–941.

6. Okamoto N, Morikawa M, Okamoto K, Habu N, Iwamoto J, Tomioka K, Saeki K, Yanagi M, Amano N, Kurumatani N. Relationship of tooth loss to mild memory impairment and cognitive impairment: findings from the Fujiwara-kyo Study. Behav Brain Funct. 2010; 6:77.

7. Makiura T, Ikeda Y, Hirai T, Terasawa H, Hamaue N, Minami M. Influence of diet and occlusal support on learning memory in rats behavioral and biochemical studies. Res Commun Mol Pathol Pharmacol. 2000; 107:269–277.

8. Fillit H, Nash DT, Rundek T, Zuckerman A. Cardiovascular risk factors and dementia. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2008; 6:100–118.

9. Lee DY, Fletcher E, Martinez O, Ortega M, Zozulya N, Kim J, Tran J, Buonocore M, Carmichael O, DeCarli C. Regional pattern of white matter microstructural changes in normal aging, MCI, and AD. Neurology. 2009; 73:1722–1728.

10. Fernando MS, Ince PG. MRC Cognitive Function and Ageing Neuropathology Study Group. Vascular pathologies and cognition in a population-based cohort of elderly people. J Neurol Sci. 2004; 226:13–17.

11. Inaba M, White L, Bell C, Chen R, Petrovitch H, Launer L, Abbott RD, Ross GW, Masaki K. White matter lesions on brain magnetic resonance imaging scan and 5-yr cognitive decline: the Honolulu-Asia Aging Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011; 59:1484–1489.

12. Gorelick PB, Scuteri A, Black SE, Decarli C, Greenberg SM, Iadecola C, Launer LJ, Laurent S, Lopez OL, Nyenhuis D, et al. Vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2011; 42:2672–2713.

13. Zoellner H. Dental infection and vascular disease. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2011; 37:181–192.

14. Holmlund A, Holm G, Lind L. Number of teeth as a predictor of cardiovascular mortality in a cohort of 7,674 subjects followed for 12 years. J Periodontol. 2010; 81:870–876.

15. Wu T, Trevisan M, Genco RJ, Dorn JP, Falkner KL, Sempos CT. Periodontal disease and risk of cerebrovascular disease: the first national health and nutrition examination survey and its follow-up study. Arch Intern Med. 2000; 160:2749–2755.

16. Stewart R, Dufouil C, Godin O, Ritchie K, Maillard P, Delcroix N, Crivello F, Mazoyer B, Tzourio C. Neuroimaging correlates of subjective memory deficits in a community population. Neurology. 2008; 70:1601–1607.

17. Joshipura KJ, Hung HC, Rimm EB, Willett WC, Ascherio A. Periodontal disease, tooth loss, and incidence of ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2003; 34:47–52.

18. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL Jr, Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, Wright JT Jr, et al. The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003; 289:2560–2572.

19. National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002; 106:3143–3421.

20. Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Report of the expert committee on the diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2003; 26:S5–S20.

21. Wahlund LO, Barkhof F, Fazekas F, Bronge L, Augustin M, Sjögren M, Wallin A, Ader H, Leys D, Pantoni L, et al. A new rating scale for age-related white matter changes applicable to MRI and CT. Stroke. 2001; 32:1318–1322.

22. Giele JL, Witkamp TD, Mali WP, van der Graaf Y. SMART Study Group. Silent brain infarcts in patients with manifest vascular disease. Stroke. 2004; 35:742–746.

23. Beck JD, Sharp T, Koch GG, Offenbacher S. A 5-year study of attachment loss and tooth loss in community-dwelling older adults. J Periodontal Res. 1997; 32:516–523.

24. Chin UJ, Ji S, Lee SY, Ryu JJ, Lee JB, Shin C, Shin SW. Relationship between tooth loss and carotid intima-media thickness in Korean adults. J Adv Prosthodont. 2010; 2:122–127.

25. Nakano K, Inaba H, Nomura R, Nemoto H, Takeda M, Yoshioka H, Matsue H, Takahashi T, Taniguchi K, Amano A, et al. Detection of cariogenic Streptococcus mutans in extirpated heart valve and atheromatous plaque specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 2006; 44:3313–3317.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download