Abstract

Leukemia cutis (LC) is defined as a neoplastic leukocytic infiltration of the skin. Few clinical studies are available on recent trends of LC in Korea. The purpose of this study was to analyze the clinical features and prognosis of LC in Korea and to compare findings with previous studies. We performed a retrospective study of 75 patients with LC and evaluated the patients' age and sex, clinical features and skin lesion distribution according to the type of leukemia, interval between the diagnosis of leukemia and the development of LC, and prognosis. The male to female ratio was 2:1, and the mean age at diagnosis was 37.6 yr. The most common cutaneous lesions were nodules. The most commonly affected site was the extremities in acute myelocytic leukemia and chronic myelocytic leukemia except for acute lymphocytic leukemia. Compared with previous studies, there was an increasing tendency in the proportion of males and nodular lesions, and LC most often occurred in the extremities. The prognosis of LC was still poor within 1 yr, which was similar to the results of previous studies. These results suggest that there is a difference in the clinical characteristics and predilection sites according to type of leukemia.

Leukemia cutis (LC) was first described by Biesiadecki (1) in 1876 and was defined as the cutaneous infiltration of malignant hematopoietic cells causing specific and non-specific skin eruptions. The clinical features of LC are variable, including macules, papules, plaques, nodules and ulcers. The lesions may be localized or disseminated and can occur on any site of the skin (2). Other previous reports in Korea found no obvious difference in clinical patterns according to leukemia type (3-5). In addition, it is not yet known whether the prognosis of cases with LC has changed with the development of new treatment modalities such as chemotherapy, radiation therapy and transplantation (6, 7).

Due to recent dramatic developments in treatment, a change in the incidence of LC might be predicted. Although some case series of LC have been reported in the literature, a limitation of previous studies was the small number of subjects and insufficient data to accurately identify the clinical characteristics of LC (3-5). LC can be found in 13% of patients with acute monocytic leukemia (AMoL) and in 10%-33% of patients with acute myelomonocytic leukemia (AMML), but is less common in patients with acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL), ranging from 1.3%-3% and 6%-10% in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) (8, 9). In contrast, CLL accounts for only 0.4%-0.5% of leukemia in Korea, and there are only two cases of LC with CLL reported in the Korean literature (10, 11). There was no case of LC with CLL in four Korean studies, including the present study, due to the low incidence of CLL in Korea (3-5). Thus, the incidence of LC according to the type of leukemia in Western countries cannot be applied to the Korean population. Since 2000, there has been no study analyzing the clinical characteristics of LC; therefore, it is difficult to identify recent trends in LC.

Cases diagnosed as LC by skin biopsy were selected from the database of the Department of Dermatology of Seoul St. Mary's Hospital and Yeouido St. Mary's Hospital. Cases were searched between the dates of April 1988 and December 2011, and 75 cases which were histologically confirmed with cutaneous leukemic infiltrate and had the underlying hematological malignancy were finally included in this study.

We performed a retrospective study of 75 cases of LC. The patients' underlying hematologic diseases were classified based on the results of bone marrow biopsies and peripheral blood analysis. We evaluated the patients' characteristics, clinical features, and prognosis according to the leukemia subtype. Cases of acute leukemia were further classified according to the French-American-British (FAB) classification (12) as acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL; L1, L2, L3), acute granulocytic leukemia (AGL; AML M1, M2, M3), acute myelomonocytic leukemia (AMML; M4), acute monocytic leukemia (AMoL; M5), acute erythrogenic leukemia (AEL; M6), or acute megakaryocytic leukemia (AMLK; M7). Chronic leukemia was classified as either chronic myelocytic leukemia (CML), chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) or myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS).

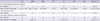

Seventy-five cases were composed of 23 patients with AGL (AML, M1, M2, M3), 11 AMML (AML, M4), 14 AMoL (AML, M5), 1 AEL (AML, M6), 18 ALL, 7 CML, and 1 MDS. The male-female ratio was 2 : 1. Mean age at diagnosis was 37.6 yr (Table 1).

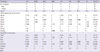

Nodules (33%), papules (30%), and plaques (17%) were the three most common types of LC lesions. Ulcer, vesicles and swelling were uncommon findings of LC. Nodules were the most common lesion in AML and ALL, whereas papules were most frequently seen in CML (Table 2).

The extremities (37%, 40/109) and trunk (28%, 30/109) were the most frequent locations of LC (Fig. 1, 2). In addition, AGL (42%, 16/38) and AMoL (63%, 10/16) lesions were most frequently seen on the extremities; ALL on the trunk (44%, 11/25) (Table 2). Most lesions were multiple (84%, 63/75), while 11 cases (16%) were solitary. Solitary lesions were most common in ALL (28%, 5/18), followed by AML (10%, 5/49).

In 58 of 75 patients (77%), LC developed after the diagnoses of leukemia. The mean interval from diagnosis of leukemia to the development of LC was 16.2 months. Four patients (5%) had skin lesions before the diagnosis of systemic leukemia at a mean interval of 2.3 months. Thirteen patients (17%) had concurrent involvement (Table 3).

Forty of 75 patients (53%) died after having been diagnosed with LC during the follow-up period of 23 yr. The mean interval between the diagnosis of LC and death was 8.3 months, and the majority died within 1 yr (88%, 35/40) (Table 4).

In this study, we analyzed the clinical characteristics and prognosis of LC using the data of 75 patients with LC. We also summarized 62 cases from three previous studies (17 cases from 1980-1989 (3), 22 cases from 1988-1995 (4), and 23 cases from 1989-1999 (5)) published in Korea and analyzed the patient sex ratio, clinical manifestations, and lesion distribution to compare with the findings of the present study. Previous studies had shown that there was no difference in clinical characteristics according to the clinical type of leukemia, and that the prognosis of patients with LC was poor (3-5) (Table 5). However, previous studies included a small number of patients and were therefore limited in accuracy. In this regard, this study is meaningful in that it analyzed 75 cases, the largest number of series in the Korean literature, over a period of 23 yr.

In the previous studies, a total 62 cases included 12 patients with AGL (AML, M1, M2, M3), 15 AMML (AML, M4), 9 AMoL (AML, M5), 2 AMMKL (AML, M7), 11 ALL, 9 CML, 3 MDS and 1 case of eosinophilic leukemia. In our study, the male-female ratio was 2:1, but in previous studies it was 1.3:1. The proportion of males was greater in our study, and there remained a tendency for LC to occur more frequently in middle-aged men. The mean age was 37.6 yr, similar to the results of previous studies (Table 1).

In this study, the most commonly clinically observed skin lesions were nodules, papules, and plaques, in decreasing order. The overall most common type of lesion was nodules (33%); nodules were also the most common lesion in AML (35%) and in ALL (39%). In the previous studies, papules were the overall most common lesions (31%), as well as being the most common lesion in AML (29%) and in ALL (33%). Nodules were the second most common lesion (26%). Compared with previous studies, nodules have increased as a proportion of all lesion types.

The predilection sites of LC according to leukemia type differ among reports. While some reports found no apparent predilection for the sites of involvement (2, 13), others reported that LC had different predilection sites according to the type of leukemia; ALL and CLL occur mainly on the face and extremities, CML shows generalized distribution, and AML is characterized by infiltration into oral mucosa (10). In this study, the extremities (37%) were the most frequent location of LC. In previous studies, the extremities (33%) and trunk (32%) were the most common location. There was no difference in the most common predilection sites between our study and previous studies. Interestingly, in contrast to the previous studies dealing with the small number of subjects, there were some differences in predilection sites according to the type of leukemia in our study. In particular, AGL lesions were most frequently seen on the extremities (42%), as were AMoL lesions (63%) and CML lesions (44%); however, most ALL lesions were found on the trunk (44%).

LC may present concurrently with bone marrow disease, may be the first sign of relapse, or may precede bone marrow infiltration by several months (2, 14). In this study, 95% of LC developed after the diagnoses of leukemia or showed concurrent involvement. Only 5% of cases had skin lesions before the diagnosis of systemic leukemia. In a previous study, 82% (18/22) of LC developed after the diagnoses of leukemia or concurrent involvement, and 18% (4/22) of LC developed before the diagnosis of systemic leukemia (4). These results demonstrate a decreasing tendency in the number of the cases in which skin lesions preceded the diagnosis of systemic leukemia due to early diagnosis of leukemia.

Because the previous studies lacked information on follow-up for treatment and prognosis, we analyzed these factors for LC in the present study. In our study, about half of patients died after the diagnosis of LC. The mean interval between diagnosis of LC and death was 8.3 months, and the majority died within 1 yr. This is also in accordance with other reports (6, 15, 16). Su et al. (15) reported that 88% of patients died within 1 yr. Shaikh et al. (16) reported that the mean survival period of patients with LC was 12.5 weeks, which is far lower than the 50 weeks reported for patients without LC. In a previous study, Jang et al. (4) reported that the mean interval between diagnosis of LC and death was 3.8 months, and Jang et al. (5) reported that it was 4.8 months. Compared to previous studies, the present study reported an extended mean interval, and this may be related to the development of new treatment modalities. Nevertheless, the poor prognosis may be explained by the fact that LC hinders a complete response to chemotherapy and occurs together with the advanced or accelerated progression of leukemia, which is frequently accompanied by infiltration into other organs such as the liver, spleen and lymph nodes (5, 6, 17, 18). LC may indicate an advanced disease and is a marker of rapid progression.

This study has a limitation because we could not compare the incidence of LC according to the type of leukemia as epidemiological data on the incidence and prevalence of leukemia patients according to the type of leukemia were unavailable. Further study is needed to analyze the incidence of LC by type of leukemia.

In conclusion, the present study found a difference in the clinical characteristics and predilection sites according to the type of leukemia. LC is a valuable marker of poor prognosis and can precede the relapse of systemic leukemia. Early detection of an extramedullary relapse is important, and follow-up by a hematologist as well as a dermatologist is essential.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Gross manifestation on face. (A) Asymptomatic, multiple, variable-sized, erythematous papules on the face. (B) Painful, oozing, erythematous, erosive patches on the cheek. (C) Tender, crusted plaque on the chin. |

| Fig. 2Gross skin lesions on the trunk or extremities. (A) Multiple, erythematous nodules on the trunk. (B) Multiple, erythematous nodules on the whole body. (C) Pruritic, erythematous papules on both extremities. (D) Solitary, reddish-brown mass on the ankle. |

References

1. Costello MJ, Canizares O, Montague M, Buncke CM. Cutaneous manifestations of myelogenous leukemia. AMA Arch Derm. 1955. 71:605–614.

2. Wagner G, Fenchel K, Back W, Schulz A, Sachse MM. Leukemia cutis - epidemiology, clinical presentation, and differential diagnoses. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2012. 10:27–36.

3. Cho KH, Jeon HP, Kim JA, Lee SK, Park SH, Kim BK. A clinicopathological study of leukemia cutis. Korean J Dermatol. 1990. 28:321–330.

4. Jang IG, Lee DW, Han CW, Kim CC, Cho BK. A clinical observation on leukemia cutis. Korean J Dermatol. 1996. 34:507–514.

5. Jang KA, Chi DH, Choi JH, Sung KJ, Moon KC, Koh JK. Leukemia cutis: a clinico-pathologic study of 23 patients. Korean J Dermatol. 2000. 38:15–22.

6. Kaddu S, Zenahlik P, Beham-Schmid C, Kerl H, Cerroni L. Specific cutaneous infiltrates in patients with myelogenous leukemia: a clinicopathologic study of 26 patients with assessment of diagnostic criteria. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999. 40:966–978.

7. Bakst RL, Tallman MS, Douer D, Yahalom J. How I treat extramedullary myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2011. 118:3785–3793.

8. Braverman IM. Skin signs of systemic disease. 1981. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders;179–196.

9. Su WP. Clinical, histopathologic, and immunohistochemical correlations in leukemia cutis. Semin Dermatol. 1994. 13:223–230.

10. Choi HS, Hahn JS, Lee KH, Cho SH. A case of leukemia cutis associated with B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Korean J Hematol. 2003. 38:147–150.

11. Moon TK, Lee BJ, Lee SH, Ahn SK, Lee WS. Leukemic macrocheilitis associated with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Korean J Dermatol. 1994. 32:1114–1118.

12. Weinstein HJ. Wyngaarden JB, Smith LH, editors. The acute leukemias. The text book of medicine. 1998. 18th ed. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders;1001–1009.

13. Watson KM, Mufti G, Salisbury JR, du Vivier AW, Creamer D. Spectrum of clinical presentation, treatment and prognosis in a series of eight patients with leukaemia cutis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006. 31:218–221.

14. Ohno S, Yokoo T, Ohta M, Yamamoto M, Danno K, Hamato N, Tomii K, Ohno Y, Kobashi Y. Aleukemic leukemia cutis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990. 22:374–377.

15. Su WP, Buechner SA, Li CY. Clinicopathologic correlations in leukemia cutis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984. 11:121–128.

16. Shaikh BS, Frantz E, Lookingbill DP. Histologically proven leukemia cutis carries a poor prognosis in acute nonlymphocytic leukemia. Cutis. 1987. 39:57–60.

17. Paydaş S, Zorludemir S. Leukaemia cutis and leukaemic vasculitis. Br J Dermatol. 2000. 143:773–779.

18. Cho-Vega JH, Medeiros LJ, Prieto VG, Vega F. Leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008. 129:130–142.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download