Abstract

High participation rates are important for maximizing the effects of a health screening program. Previous studies have suggested that individual or regional characteristics have effects on health behaviors. In this study, we investigated the determinants of participation in the National Screening Program for Transitional Ages by simultaneously analyzing individual and area-level factors by multilevel analysis. A total of 1,081,216 subjects, aged 40 and 66 yr and nested in 254 areas, were included. There was a significant variation in participation rates across the areas even after adjusting for individual and area-level variables. Among the individual-level variables, increasing age, sex, higher income, and mild disability grade were associated with a higher participation rate. In urban areas, the 40-yr-old group had higher participation rates than the 66-yr-old group. Deprived areas had significantly high participation rates for both age groups. The number of screening centers per 1,000 inhabitants had no significant effect on participation in the screening program. In conclusion, regional characteristics are associated with participation rates independent of personal features and regional factors have differential effects with respect to age. A multi-dimensional approach is recommended to promote participation in health screening programs.

Health screening programs aim primarily to reduce the mortality of target diseases by early detection and effective treatment (1). High participation rates should be ensured to maximize the benefits of such screening programs. It is known that individual factors such as age, sex, disability (2, 3), and socioeconomic status (4-6) affect the rate of participation. Moreover, psychosocial factors such as knowledge and beliefs about a program, attitude towards a screening program, and cultural background (7-9) are associated with participation. However, previous studies have mainly focused on individual characteristics and largely ignored regional characteristics.

Understanding the effects of regional characteristics is important because our health and behavior are affected by the environment and features of the region we inhabit (10). Additionally, some studies have reported that regional socioeconomic factors such as area income, unemployment, and education levels significantly affect the participation rate in health screening programs independent of individual characteristics (11-13). However, those studies were conducted as parts of cancer screening programs (8, 14-17) or involved study populations in limited areas (18, 19). Furthermore, individual and area-level variables were separately analyzed using single-level multivariable regression (12, 20).

The Republic of Korea Government has actively carried out health screening programs in an effort to detect diseases early and to improve public health. Since their introduction in the 1980s, the coverage of periodic national health screening programs has been expanding. In 2007, a new national health screening program, the National Screening Program for Transitional Ages, was added to the existing program (21). It covers those who are 40 and 66 yr old, including Medicaid recipients who were excluded from the national general health screening program.

In this study, using the whole data of the National Screening Program for Transitional Ages, we simultaneously analyzed individual and area-level factors by multilevel analysis to find the determinants of participation in the national screening program. Multilevel analysis allows the examination of area and individual-level factors simultaneously. Most studies in Korea have approached individual or area-level factors separately or controlled different level factors at the same level. This may have led to over/underestimation of the effect of different level factors. Multilevel analysis can examine both inter-individual and intergroup variation and allows researchers to deal simultaneously with individuals at a micro-level and areas at a macro-level.

Although previous studies have suggested various individual and regional determinants of participation in health screening programs, we selected individual and area-level factors by considering practical and political implications. Eventually, we selected 3 domains based on regional characteristics: level of urbanization, regional deprivation, and medical supply. We hypothesized that more urbanized and less deprived areas would have higher participation rates, and that the number of screening centers would exhibit a positive relation with participation.

Our study is based on the data of the National Screening Program for Transitional Ages in 2008 and 2009 obtained from the National Health Insurance Corporation (NHIC). In Korea, the National Health Insurance provides mandatory universal health insurance to nearly all Koreans (96.9%); others are covered by a public assistance plan (i.e., Medicaid). As the Ministry of Health and Welfare entrusts the handling of claims to the NHIC, the data of Medicaid enrollees are also managed by the NHIC. We excluded the insured employee group from our study population because both employers and employees may incur penalties if they do not undergo health checkups. As the NHIC provided data without identification codes for the dependents of the employee insured group at the beginning of our study, we could not analyze these dependents in our study.

Among the data of 1,081,249 potentially eligible subjects in 254 municipal districts, the personal health registry data of 1,081,216 were used after excluding subjects who had duplicate or missed identification numbers. Eligible area-level data were collected from various sources. We merged the area and individual-level data using the local address codes of the municipal districts (Fig. 1).

Individual-level variables were derived from the insurance registry data of the NHIC. The residential address codes of the study population were all deleted and replaced with simple numbers to ensure their privacy. We selected the final individual variables according to a review of previous studies and ease of interpretation. The variables are as follows: 1) year (2008 vs 2009), 2) age (40 vs 66 yr old), 3) sex (male vs female), 4) health insurance type (self-employed insured vs Medicaid recipients), 5) health insurance premium, and 6) disability grade according to the legal classification of severity according to Article 2 of the Welfare of Disabled Persons Act (22).

Health insurance premiums are determined according to monthly income levels in Korea; we used health insurance premium as an indicator of individual income level. We divided health insurance premium into quintiles from group 1 (lowest) to group 5 (highest) according to the monthly health insurance premium amount. The Medicaid recipient group, who does not pay at all, was designated as group 0. Disability was graded from 1 (severe) to 6 (mild) according to the legal category of disability severity. Subjects without any disability were categorized as the non-disabled group.

Initially, we collected 199 area-level variables from various sources, such as the 2005 Population Census of the Korea National Statistical Office; 2005-2006 Benefit Recipient data; 2008 Korean Medical Association's membership survey; 2008 land registration statistics of the Ministry of Land, Transport, and Maritime Affairs; and the 2010 National Health Insurance Corporation. Among 199 potential variables, we chose 3 area-level variables based on statistical significance from univariate analyses and health policy implications: 1) the proportion of agriculture, forestry, and fishery workers (%) as an inverse index of the urbanization of the region; 2) the Composite Deprivation Index (CDI) score, which represents the level of deprivation in an area (23); and 3) the number of screening centers per 1,000 inhabitants, which indicates the level of medical supply. All variables except CDI score were based on data from 2007.

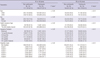

We used the CDI as the parameter for regional deprivation. The CDI is calculated according to 5 domains: 1) unemployment, 2) poverty, 3) housing, 4) labor, and 5) social network. The proxy variables of the 5 domains are as follows: 1) the proportion of unemployed males, 2) the percentage of recipients receiving National Basic Livelihood Security Act benefits, 3) the proportion of households under the minimum housing standard, 4) the proportion of people with low social class, and 5) the proportion of single-parent households (Table 1). Previous studies have reported that the CDI was more suitable in Korea than the Townsend or Carstairs indices, which were developed in England and widely used as indicators for regional deprivation (23, 24).

We divided the study population into 2 groups according to age: subjects were 40 yr and 66 yr old. Multilevel analysis was performed on 1,081,216 individuals (level 1) nested within 254 municipal districts (level 2). A 2-level logistic regression model using the Markov Chain Monte Carlo method was constructed to estimate the average relationships between participation in the national health screening program and individual-level variables across all regions (i.e., individual fixed parameters) and between the variation between municipal districts (i.e., regional random variance), and the effects of area-level variables on participation in the screening program (i.e., regional fixed parameters).

We performed multilevel logistic regression analyses adjusting for both individual and area-level variables as fixed effects and allowed for heterogeneity between areas on a step-by-step basis. First, a null model with no explanatory variable was analyzed for the existence of variance between areas (null model). Second, to calculate the proportion of variance related to the region remaining after adjusting for individual-level variables, individual-level variables were added into the null model (Model 1). Finally, individual and area-level variables were simultaneously introduced into the model (Model 2). The area-level random effect of the intercept was assumed to have a normal distribution. We calculated the proportion of variance related to the region (intraclass correlation: ICC) as approximately: regional variance/(regional variance + π2/3). In addition, we tested area-level factors using a random slope model, and tested interactions between individual-level and area-level factors.

All statistical analyses were performed using STATA 12.0 (STATA Corp, Houston, TX, USA) and MLwiN 2.25 (University of Bristol, UK). Statistical significance was defined as a 2-sided P value less than 0.05.

Table 2 lists the baseline characteristics of the study population. Of the 1,081,216 subjects, 410,168 (37.9%) participated in the screening program. The participation rate of the 40-yr-old group was lower than that of the 66-yr-old group (30.2% vs 50.4% in 2008; 34.5% vs 54.6% in 2009). More women participated in the screening program. The sex gap was more prominent in the 40-yr-old group than in the 66-yr-old group (13.5% vs 2.6%). Income level (health insurance premium) was generally positively related to the participation rate in both age groups, except in the first and second income quintiles in the 40-yr-old group. Severity of disability was negatively associated with participation rate.

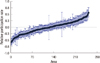

Table 3 shows the results of multilevel analysis, which included individual and area-level variables in a hierarchical manner. There was significant variance with respect to participation rates across the area in the null model (log-odds [β], 0.04; standard error [SE], 0.004) (Fig. 2). When the null model was adjusted with individual-level variables (Model 1), the regional variance decreased (β, 0.036; SE, 0.004). All individual-level variables were significantly associated with participation rate. After the null model was simultaneously adjusted with individual and area-level variables (Model 2), the regional variance decreased further (β, 0.031; SE, 0.003). However, some unexplained variance across areas was still observed.

There were lower participation rates in the first and second premium quintile groups than in the Medicaid recipient group, while participation rates were higher in the third, fourth, and fifth income quintiles than in the Medicaid recipient group. Participation rates for subjects with severe disabilities (grades 1 and 2) were lower than for subjects without disabilities, while the participation rate was higher for the mild disability groups.

The proportion of agriculture, forestry, and fishery workers in an area was negatively associated with participation rate (β, -0.005; SE, 0.002). In addition, a higher CDI was significantly associated with a higher participation rate (β, 0.001; SE <0.0001). The number of screening centers per 1,000 inhabitants did not significantly influence participation in the screening program (β, 0.493; SE, 0.404). ICCs were low in all models, and when we introduced area-level variables into Model 1, 18% of ICCs decreased.

When we tested the random slope model of area-level factors, the result was not significant (data not shown). When we tested interaction between different level factors, there was a significant inverse interaction between health insurance premium and the proportion of agriculture, forestry, and fishery workers in an area (Table 4). The CDI had a positive interaction with health insurance premium, but the number of screening centers per 1,000 inhabitants had no significant interaction with the premium level (Table 4).

Table 5 shows the results of the multilevel analysis, which included individual and area-level variables in a hierarchical manner. There was significant variance in participation rates across the area in the null model (Fig. 3). Individual-level variables exhibited similar effects on participation in screening before and after controlling for area-level variables. The exception was that there was less participation by the Medicaid recipient group in the screening program than all income quintiles of the insured self-employed groups.

The proportion of agriculture, forestry, and fishery workers was positively related with the participation rate (β, 0.022; SE, 0.002). This contradicted the results obtained for the 40-yr-old group. The CDI was significantly positively related to screening program participation (β, 0.001; SE <0.0001). The number of screening centers per 1,000 inhabitants had no significant effect on the participation rate (β, 0.578; SE, 0.362). Although ICCs were still low, they were higher than that of the 40-yr-old group in all the models. When we compared Model 2 with Model 1, there was a 40% decrease in the ICC in Model 2.

Although we tested the random slope model of area-level factors, there was no significant effect, as was observed in the 40-yr-old group (data not shown). When we tested the interaction between inter-level factors, the results were similar to those of the 40-yr-old group. Health insurance premium level and the proportion of agriculture, forestry, and fishery workers in an area exhibited an inverse interaction (Table 4). There was a positive interaction between CDI score and the health insurance premium (Table 4). There was no significant interaction between the number of screening centers per 1,000 inhabitants and health insurance premium (Table 4).

To our knowledge, this is the first study investigating the individual and area-level determinants of participation in the national general health screening program in Korea with a multilevel analysis approach. We determined that regional characteristics had significant independent effects on participation in the national screening program. We also compared all Medicaid recipient subjects with insured subjects. To date, no study has used the nationwide data of Medicaid recipients to investigate their behaviors related health screening.

There were significant regional variations in all the models of both age groups. When we adjusted individual-level factors, ICCs in the 40 and 66-yr-old groups were 0.011 and 0.025, respectively. This means that the inter-area variance was smaller for the 40-yr-old group and that individual characteristics had a larger influence in this group. When we adjusted area-level factors additionally, the ICC decrease was more prominent in the 66-yr-old group. This indicates that a larger part of the regional variance can be explained by the area-level factors used in the 66-yr-old group. Consequently, we can expect the 66-yr-old group to be influenced more by regional characteristics than the 40-yr-old group.

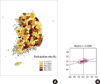

As we had hypothesized, level of urbanization had a significant effect on participation in the national screening program. However, the effect was different with respect to age. In the 40-yr-old group, the participation rates of residents in urban areas were higher than those in rural areas were. In contrast, in the 66-yr-old group, the participation rates of subjects in rural areas were higher than those in urban areas were. The relationship between urbanization and participation in health screening programs is still controversial. According to previous Korean and Japanese studies (8, 17, 25), the participation rates of subjects in urban or metropolitan areas in national health screening programs were lower. In contrast, some studies in other countries (12, 26) reported lower participation rates in rural areas. The role of mobile health screening services may help explain our results. In Korea, according to the Framework Act in Health Examination Law, only agencies licensed by the Minister of Health and Welfare can provide mobile health screening services outside medical institutions. Mobile health screening services usually target mountainous and rural areas with poor accessibility to health screening centers. With their instruments, examination staffs access the target location via a specialized bus or container car and conduct general health checkups (physical examination, blood test, urine test, and chest radiography) and cancer screenings (stomach, breast, colon, liver, and cervical cancer). Although there has been some criticism about the low quality of such screening services and quality controls, mobile health screening services have steadily been extended to rural municipal districts. In our study, the areas with high participation rates were concentrated in the mountainous and rural areas (Fig. 4, 5). This was more prominent in the 66-yr-old group. As most subjects in this group are retired, they may encounter fewer time constraints to utilizing the screening service than those in the 40-yr-old group, who are still actively employed. This could be responsible for the differing effect of mobile health screening services in both age groups.

In this study, participation rates were significantly higher in deprived areas. This is contrary to previous findings reporting a negative effect of regional deprivation in health screening programs (12, 13, 20, 27). The national health screening program in Korea is a very unique program targeting various diseases and is executed nationwide with political support. Our findings indicate that interventions and political support targeting deprived areas in the national health screening program, such as through mobile health screening services, advertisements, and reminder services, may be effective in improving participation rates. However, the participation rate of the low health insurance premium group was also low at the individual level. When we tested interaction between individual-level insurance premiums and regional deprivation, we found that the gap of participation rate according to income level widened as regional deprivation increased in both age groups. This implies that interventions targeting deprived subjects are not sufficiently effective or that the effect of those interventions is not properly delivered to low-income groups. We suspect that the effect of interventions for improving participation mostly reach the higher premium level groups first in deprived areas. Hence, although the participation rate of the deprived area might be higher, there would continue to be inequality at the individual level.

Contrary to our hypothesis, the number of screening centers per 1,000 inhabitants had no significant effect on participation in the screening program. Pornet et al. (13) reported no relationship between the number of screening centers and participation in cancer screening in France. However, other studies (28, 29) have suggested that the density of screening facilities is important in cancer screening participation. Our result demonstrates that a mere numeric increase of medical supplies in the national health screening program does not lead to an increase in the participation rate. We believe that mobile health screening services may play an important role in areas with few screening centers. In Korea, there are more screening centers in urban areas than in rural areas. Mobile health screening services alleviate the shortage of centers and improve accessibility. Hence, this leads to a weakening of the effect of the number of screening centers. We can also expect several screening centers to conduct most of the national health screening programs in an area intensively, and that numerous screening centers are not required.

We also determined that all individual-level variables (i.e., age, sex, health insurance type, insurance premium, and disability grade) had significant impacts on participation even after adjusting for area-level variables. Previous Korean studies (8, 14, 18, 26) analyzed these variables at a single level using multivariate regression models. Such models can under/overestimate the effect of regional characteristics. Multilevel analysis allowed us to simultaneously investigate and explain the effects of individual and area-level variables. When we carried out multilevel analysis, these individual-level variables were consistent after adjusting for area-level variables.

Although income level was positively associated with participation, which is consistent with the results of previous studies (14, 25, 29, 30), the participation rates in the first and second income quintiles in the 40-yr-old group were lower than that of Medicaid recipients. In the National Screening Program for Transitional Ages, all health screening services are offered free of charge and there is almost no economic barrier. However, since screening programs are conducted during the day and on weekdays, working people may face time constraints, which may hinder their participation in the screening program. Although most in the 66-yr-old group were retirees, most in the 40-yr-old group had jobs and were actively employed. Unlike the insured group, 40-yr-old Medicaid recipients did not have regular jobs and had relatively fewer time constraints on participation in screening programs. Differing time constraints based on age, insurance type, and income level might play an important role in the difference in participation rates. Thus, the 66-yr-old group and Medicaid recipients might participate more in health screenings than the 40-yr-old insured group. A subsequent study using variables on time constraints and their burden would be necessary to evaluate the role of time constraints.

Our study has some limitations. First, although we used the complete data of the 40 and 66-yr-old screening program subjects, their results cannot be generalized to the entire population. However, if we focus our findings on the National Screening Program for Transitional Ages, our restricted sample is entirely acceptable. Second, we could not include dependents of the insured employee group in our study. They are not obliged to participate in the national screening program, and their health behaviors may differ from our study population. Future studies should include dependents of the insured employee group and evaluate their characteristics. Third, this study did not include private health screening programs. Private health screening programs are common in Korea. The participants of private health screening programs may not participate in national health screening programs. It was impossible to determine the actual participation rates of private health screening programs from our data. However, participation in private health screening programs is more common among higher-income groups and those with health insurance. Therefore, the trends of participation rates according to income level would not change significantly even if we had included the data of private screening programs. Fourth, when we adjusted for all individual and area-level variables, significant unexplained regional variance in participation rates remained. This means that there are other factors affecting participation in national health screening programs. If we were able to include variables about attitudes towards screening programs, the quality of screening centers, and barriers to participation, we could elucidate this variance in greater detail. Finally, data regarding individual residence duration were unavailable. It is possible that regional characteristics completely affect individuals over time.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that regional characteristics have independently significant effects on individual participation in national health screening programs. They also have different interactions with individual characteristics such as age and income level. To increase participation rates in national health screening programs, tailored approaches that consider the characteristics of the target population and region simultaneously are required.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 2

Regional distribution of the participation rate in the 40-yr-old group, null model. Estimated relative participation rates were illustrated with 95% confidential intervals.

Fig. 3

Regional distribution of the participation rate in the 66-yr-old group, null model. Estimated relative participation rates were illustrated with 95% confidential intervals.

Fig. 4

Regional distribution of the participation rate (A) and spatial correlation of the regional participation rate. Values range from -1 (indicating perfect dispersion) to +1 (perfect correlation) (B) in the 40-yr-old group.

Fig. 5

Regional distribution of the participation rate (A) and spatial correlation of the regional participation rate. Values range from -1 (indicating perfect dispersion) to +1 (perfect correlation) (B) in the 66-yr-old group.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the staffs of the Korean National Health Insurance Corporation for their thoughtful assistance. The authors declare no conflict of interests.

References

1. Lee WC, Lee SY. National health screening program of Korea. J Korean Med Assoc. 2010. 53:363–370.

2. Park JH, Lee JS, Lee JY, Hong JY, Kim SY, Kim SO, Cho BH, Kim YI, Shin Y, Kim Y. Factors affecting national health insurance mass screening participation in the disabled. J Prev Med Public Health. 2006. 39:511–519.

3. Park JH, Lee JS, Lee JY, Gwack J, Park JH, Kim YI, Kim Y. Disparities between persons with and without disabilities in their participation rates in mass screening. Eur J Public Health. 2009. 19:85–90.

4. Sung NY, Park EC, Shin HR, Choi KS. Participation rate and related socio-demographic factors in the national cancer screening program. J Prev Med Public Health. 2005. 38:93–100.

5. Kwak MS, Park EC, Bang JY, Sung NY, Lee JY, Choi KS. Factors associated with cancer screening participation, Korea. J Prev Med Public Health. 2005. 38:473–481.

6. Kim RB, Park KS, Hong DY, Lee CH, Kim JR. Factors associated with cancer screening intention in eligible persons for national cancer screening program. J Prev Med Public Health. 2010. 43:62–72.

7. Rutter DR. Attendance and reattendance for breast cancer screening: a prospective 3-year test of the theory of planned behaviour. Br J Health Psychol. 2000. 5:1–13.

8. Hahm MI, Choi KS, Kye SY, Kwak MS, Park EC. Factors influencing the intention to have stomach cancer screening. J Prev Med Public Health. 2007. 40:205–212.

9. Kye SY, Han EO, Park KH. Predictors of regular gastric cancer screening among Koreans. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2010. 11:1315–1320.

10. Robert SA. Community-level socioeconomic status effects on adult health. J Health Soc Behav. 1998. 39:18–37.

11. Pruitt SL, Shim MJ, Mullen PD, Vernon SW, Amick BC 3rd. Association of area socioeconomic status and breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer screening: a systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009. 18:2579–2599.

12. Siahpush M, Singh GK. Sociodemographic variations in breast cancer screening behavior among Australian women: results from the 1995 National Health Survey. Prev Med. 2002. 35:174–180.

13. Pornet C, Dejardin O, Morlais F, Bouvier V, Launoy G. Socioeconomic determinants for compliance to colorectal cancer screening: a multilevel analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2010. 64:318–324.

14. Jang SN, Cho SI, Hwang SS, Jung-Choi K, Im SY, Lee JA, Kim MK. Trend of socioeconomic inequality in participation in cervical cancer screening among Korean women. J Prev Med Public Health. 2007. 40:505–511.

15. Lee K, Lim HT, Park SM. Factors associated with use of breast cancer screening services by women aged >or= 40 years in Korea: the third Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005 (KNHANES III). BMC Cancer. 2010. 10:144.

16. Roh WN, Lee WC, Kim YB, Park YM, Lee HJ, Meng KH. An analysis on the factors associated with cancer screening in a city. Korean J Epidemiol. 1999. 21:81–92.

17. Fukuda Y, Nakamura K, Takano T. Reduced likelihood of cancer screening among women in urban areas and with low socio-economic status: a multilevel analysis in Japan. Public Health. 2005. 119:875–884.

18. Chun EJ, Jang SN, Cho SI, Cho Y, Moon OR. Disparities in participation in health examination by socio-economic position among adult Seoul residents. J Prev Med Public Health. 2007. 40:345–350.

19. Fukuda Y, Nakamura K, Takano T. Accumulation of health risk behaviours is associated with lower socioeconomic status and women's urban residence: a multilevel analysis in Japan. BMC Public Health. 2005. 5:53.

20. Dailey AB, Brumback BA, Livingston MD, Jones BA, Curbow BA, Xu X. Area-level socioeconomic position and repeat mammography screening use: results from the 2005 National Health Interview Survey. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011. 20:2331–2344.

21. Kim HS, Shin DW, Lee WC, Kim YT, Cho B. National screening program for transitional ages in Korea: a new screening for strengthening primary prevention and follow-up care. J Korean Med Sci. 2012. 27:S70–S75.

22. The National Assembly of the Republic of Korea. Disabled persons welfare act. accessed on 4 November 2012. Available at http://likms.assembly.go.kr.

23. Shin H, Lee S, Chu JM. Development of composite deprivation index for Korea: the correlation with standardized mortality ratio. J Prev Med Public Health. 2009. 42:392–402.

24. Chu JM, Park JI, Cho MR, Choi SJ, Im JH, Shin HS. Environmental policy for low-income population in urban area. No RE-02S. 2007. Seoul: Korea Environment Institute;106–109.

25. Kwon YM, Lim HT, Lee K, Cho BL, Park MS, Son KY, Park SM. Factors associated with use of gastric cancer screening services in Korea. World J Gastroenterol. 2009. 15:3653–3659.

26. Maxwell CJ, Bancej CM, Snider J. Predictors of mammography use among Canadian women aged 50-69: findings from the 1996/97 National Population Health Survey. CMAJ. 2001. 164:329–334.

27. Schootman M, Jeffe DB, Baker EA, Walker MS. Effect of area poverty rate on cancer screening across US communities. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006. 60:202–207.

28. Meersman SC, Breen N, Pickle LW, Meissner HI, Simon P. Access to mammography screening in a large urban population: a multi-level analysis. Cancer Causes Control. 2009. 20:1469–1482.

29. Coughlin SS, Leadbetter S, Richards T, Sabatino SA. Contextual analysis of breast and cervical cancer screening and factors associated with health care access among United States women, 2002. Soc Sci Med. 2008. 66:260–275.

30. Kim YB, Ro WO, Lee WC, Park YM, Meng KH. The influence factors on cervical and breast cancers screening behavior of women in a city. J Korean Soc Health Educ Promot. 2000. 17:155–170.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download