Abstract

A 21-year-old man with diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) displayed short and clubbed fingers and marked eyebrow, which are typical of Hajdu-Cheney Syndrome (HCS). Laboratory findings confirmed type 1 diabetes mellitus (DM). After conservative care with hydration and insulin supply, metabolic impairment was improved. Examinations of bone and metabolism revealed osteoporosis and craniofacial abnormalities. The mutation (c.6443T>G) of the NOTCH2 gene was found. The patient was diagnosed with HCS and DM. There may be a relationship between HCS and DM, with development of pancreatic symptoms related to the NOTCH2 gene mutation.

Hajdu-Cheney syndrome (HCS) is a rare skeletal dysplasia that is characterized by acro-osteolysis, distinctive craniofacial and skull abnormality in radiography, dental abnormalities and osteoporosis (1). HCS was first described in 1948 (2) and later in 1965 (3). It is an autosomal dominant condition with sporadic cases. Mutations in the NOTCH2 gene cause HCS (4). About 60 cases of HCS have been reported, but most described the relationship between HCS and skeletal abnormalities such as osteoporosis and fracture (5, 6). So far, there have been no reports about the relationship between HCS and diabetes mellitus (DM). Here, we report a case of familial HCS presenting with diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA).

A 21-yr-old Korean man was referred to the Department of Endocrinolgy and Metabolism from his primary physician for proper management of hyperglycemia and metabolic impairment on September 21 of year 2012. During the 2 yr since the patient's discharge from military service he had lost approximately 10 kg in body weight. At admission, he complained of polyuria and polydipsia. He had no known medical past history or fracture history, but his mother and elder brother had been diagnosed with HCS along with osteoporosis and multiple compression fractures of the spine (7, 8). On admission the patient showed stable vital signs and alert mental status. Blood pressure was 107/63 mmHg and pulse rate was 59/min. His height was 175 cm (50 percentile) and weight was 55 kg (10 percentile). The physical examination revealed dysmorphic features, such as marked eyebrow, which was similar to that of his brother in whom HCS had been diagnosed at the age of 20. Short and clubbed fingers were found (Fig. 1). Laboratory investigations revealed hemoglobin of 11.8 g/L, total white blood cell count of 4,800/µL (73% neutrophils). Serum biochemistry, hormones, and bone markers were tested (Table 1). No antibody to glutamic acid decarboxylase was detected. Arterial blood gas analysis revealed metabolic acidosis (pH 7.318, base excess -15.2 mM/L, bicarbonate 8.6 mM/L) with incomplete respiratory compensation (pCO2 17.2 mmHg). Urine analysis revealed that specific gravity of 1.024, strong positive in glucose and ketone bodies. A chest X-ray was normal and electrocardiography showed normal sinus rhythm. After an initial treatment for DKA, evaluations for metabolic bone disease were performed. Laboratory findings showed follicle-stimulating hormone 0.7 IU/L, luteinizing hormone 1.2 IU/L, testosterone 2.25 ng/mL (7.8075 nM/L), osteocalcin 8.9 ng/mL (1.5219 nM/L), 25-hydroxy-Vitamin D 5.7 ng/mL (14.2272 nM/L), intact parathyroid hormone <8 ng/L, and urine N-telopeptide 151 nM/mM creatinine. A hand X-ray revealed brachydactyly of the 5th finger of both hands (Fig. 2). Thoracolumbar spine X-ray revealed a fracture of T12 and L3 (Fig. 3). Skull X-ray revealed wormian bone (Fig. 4). Bone mineral density revealed osteoporosis (L1-L2 0.826 g/cm2, T-score -2.6, Z-score -2.5, total femur 1.203 g/cm2, T-score 2.0, Z-score 1.8) (Fig. 5). To confirm the diagnosis of HCS, DNA sequencing was conducted. The sequence analysis revealed that the patient and his mother had a heterogenetic mutant allele in the NOTCH2 gene (c.6443T>G) (Fig. 6) leading to an amino acid substitution from a leucine to a stop codon (p.Leu2148*) (Fig. 7). The patient was diagnosed with HCS and DKA. To manage DKA, fluid resuscitation and insulin treatment was initiated. His metabolic acidosis normalized. Since then the patients has been treated with 1,250 mg of calcium carbonate and 1,000 IU of cholecalciferol per day under the diagnosis of osteoporosis and compression fracture due to HCS, and with 5 units of basal insulin and 7 units of pre-prandial insulin injection for type 1 DM. Laboratory analyses conducted during the course of treatment showed improved HbA1c (7.5%) and fasting glucose (175.8 mg/dL or 9.768 mM/L).

HCS has been reported under various names including acroosteolysis syndrome, arthro-dento-osteodysplasia, cranio-skeletal dysplasia with acroosteolysis, hereditary osteodysplasia with acroosteolysis, and familial osteodysplasia (9). Reported phenotypes and clinical features of HCS are as varied as the terms. In this case, the patient did not show acro-osteolysis probably due to delayed expression of clinical phenotype compared to other family members. Brennan and Pauli (9) reported the evolution of phenotypes and clinical problems in HCS cases. In their report, most cases showed skeletal abnormalities and some showed renal and dermatological abnormalities. Although rare, intestinal malrotations were evident. There has been no report of DKA in association with HCS until now.

Recently, the mechanism of HCS has been clarified. Simpson et al. reported that a restricted range of mutations in the terminal exon of NOTCH2 underlie HCS (4). After binding to their ligand, Notch receptor undergoes changes that lead to translocation of their intracellular domain to the nucleus, activating the transcription of Notch target genes that have a dominant role in skeletal development and bone remodeling (10). These findings indicate the critical role of NOTCH2 signaling in the regulation of bone mass, which has been further supported by the recent association of common variants in JAG1 with bone mineral density and osteoporotic fractures (11). Mutations in NOTCH2 have previously been observed in Alagille syndrome, a multisystem monogenic disorder in which the majority of affected subjects harbor mutations in the gene encoding the Notch ligand JAG1 (12). However, there are substantial differences between Alagille syndrome and HCS in attributes including cholestasis, renal problem, and facial dysmorphologies (13).

DKA is an acute complication of DM, which is usually seen in type 1 DM. It occurs because of the relative insufficiency of insulin. There has been no report about the linking of HCS and DM, although several studies addressed the pancreas and Notch signaling. Different levels of Notch signaling driving distinct behaviors were reported in a progenitor population (14). Notch 1 is the first Notch gene expressed in the pancreatic epithelium, and its co-expression with HES 1 suggests that the Notch 1 pathway is activated. Notch 2 expression follows later when pancreatic buds branch and is restricted to embryonic ducts, which are believed to be the source for endocrine and exocrine stem cells (15). Activation of Notch at a relatively early stage of pancreatic development in cells expressing Pdx1 results in failure to develop both endocrine and acinar cells with the remaining pancreatic cells trapped in a relatively undifferentiated state. The effects of Notch activation in endocrine precursor cells in the pancreas have been examined in limited detail. Recently, Li et al. (16) examined the effect of conditionally activating Notch signaling in early and late endocrine precursor cells expressing Ngn3 or NeuroD1 in the pancreas using a mouse model. Unexpectedly, the activation of Notch in Ngn3Þ cells did not prevent the initiation of endocrine differentiation in the pancreas. However a number of islet cell types failed to mature in the pancreas. Many cells switched to a duct cell fate in pancreas. Cells that are suppressed by Notch subsequently differentiate into acinar cells, whereas duct and endocrine populations form predominantly from the wild-type cells (17). Inhibition of the NOTCH effector HES1 using short hairpin RNA leads to redifferentiation of expanded B-cell-derived cells (18). The previous data support a relationship between HCS and DM. However, we could not prove such a mechanism. Further studies on the molecular mechanism of HCS and DM linkage are required.

Until this case, there has been no reported case of DKA with HCS. The present case indicates that there may be a link between HCS and DM in regard to the mutation of NOTCH2. Such a molecular mechanism might be associated with NOTCH2 signals and pancreatic beta cells. Confirmation awaits further studies of the relationship between insulin secretion and NOTCH2 signaling.

Figures and Tables

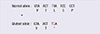

Fig. 2

Radiography of the patient's hand. Arrows show brachydactyly of the 5th finger of each hand, but without obvious osteoporosis or acro-osteolysis.

References

1. Currarino G. Hajdu-Cheney syndrome associated with serpentine fibulae and polycystic kidney disease. Pediatr Radiol. 2009; 39:47–52.

2. Hajdu N, Kauntze R. Cranio-skeletal dysplasia. Br J Radiol. 1948; 21:42–48.

3. Cheney WD. Acro-osteolysis. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1965; 94:595–607.

4. Simpson MA, Irving MD, Asilmaz E, Gray MJ, Dafou D, Elmslie FV, Mansour S, Holder SE, Brain CE, Burton BK, et al. Mutations in NOTCH2 cause Hajdu-Cheney syndrome, a disorder of severe and progressive bone loss. Nat Genet. 2011; 43:303–305.

5. Ornetti P, Tavernier C. Osteoporotic compression fracture revealing Hajdu-Cheney syndrome. Joint Bone Spine. 2012; 79:514–515.

6. Stathopoulos IP, Trovas G, Lampropoulou-Adamidou K, Koromila T, Kollia P, Papaioannou NA, Lyritis G. Severe osteoporosis and mutation in NOTCH2 gene in a woman with Hajdu-Cheney syndrome. Bone. 2013; 52:366–371.

7. Han EJ, Mun JI, An SY, Jung YJ, Kim OH, Chung YS. A case report of Hajdu-Cheney syndrome. Endocrinol Metab. 2010; 25:152–156.

8. Narumi Y, Min BJ, Shimizu K, Kazukawa I, Sameshima K, Nakamura K, Kosho T, Rhee Y, Chung YS, Kim OH, et al. Clinical consequences in truncating mutations in exon 34 of NOTCH2: report of six patients with Hajdu-Cheney syndrome and a patient with serpentine fibula polycystic kidney syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2013; 161A:518–526.

9. Brennan AM, Pauli RM. Hajdu-Cheney syndrome: evolution of phenotype and clinical problems. Am J Med Genet. 2001; 100:292–310.

10. Zanotti S, Canalis E. Notch regulation of bone development and remodeling and related skeletal disorders. Calcif Tissue Int. 2012; 90:69–75.

11. Kung AW, Xiao SM, Cherny S, Li GH, Gao Y, Tso G, Lau KS, Luk KD, Liu JM, Cui B, et al. Association of JAG1 with bone mineral density and osteoporotic fractures: a genome-wide association study and follow-up replication studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2010; 86:229–239.

12. McDaniell R, Warthen DM, Sanchez-Lara PA, Pai A, Krantz ID, Piccoli DA, Spinner NB. NOTCH2 mutations cause Alagille syndrome, a heterogeneous disorder of the notch signaling pathway. Am J Hum Genet. 2006; 79:169–173.

13. Majewski J, Schwartzentruber JA, Caqueret A, Patry L, Marcadier J, Fryns JP, Boycott KM, Ste-Marie LG, McKiernan FE, Marik I, et al. FORGE Canada Consortium. Mutations in NOTCH2 in families with Hajdu-Cheney syndrome. Hum Mutat. 2011; 32:1114–1117.

14. Ninov N, Borius M, Stainier DY. Different levels of Notch signaling regulate quiescence, renewal and differentiation in pancreatic endocrine progenitors. Development. 2012; 139:1557–1567.

15. Lammert E, Brown J, Melton DA. Notch gene expression during pancreatic organogenesis. Mech Dev. 2000; 94:199–203.

16. Li HJ, Kapoor A, Giel-Moloney M, Rindi G, Leiter AB. Notch signaling differentially regulates the cell fate of early endocrine precursor cells and their maturing descendants in the mouse pancreas and intestine. Dev Biol. 2012; 371:156–169.

17. Afelik S, Qu X, Hasrouni E, Bukys MA, Deering T, Nieuwoudt S, Rogers W, Macdonald RJ, Jensen J. Notch-mediated patterning and cell fate allocation of pancreatic progenitor cells. Development. 2012; 139:1744–1753.

18. Bar Y, Russ HA, Sintov E, Anker-Kitai L, Knoller S, Efrat S. Redifferentiation of expanded human pancreatic β-cell-derived cells by inhibition of the NOTCH pathway. J Biol Chem. 2012; 287:17269–17280.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download