Abstract

Although pandemic community-associated (CA-) methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) ST30 clone has successfully spread into many Asian countries, there has been no case in Korea. We report the first imported case of infection caused by this clone in a Korean traveler returning from the Philippines. A previously healthy 30-yr-old Korean woman developed a buttock carbuncle while traveling in the Philippines. After coming back to Korea, oral cephalosporin was given by a primary physician without any improvement. Abscess was drained and MRSA strain isolated from her carbuncle was molecularly characterized and it was confirmed as ST30-MRSA-IV. She was successfully treated with vancomycin and surgery. Frequent international travel and migration have increased the risk of international spread of CA-MRSA clones. The efforts to understand the changing epidemiology of CA-MRSA should be continued, and we should raise suspicion of CA-MRSA infection in travelers with skin infections returning from CA-MRSA-endemic countries.

A recent global epidemiology of Staphylococcus aureus is characterized by emergence of community-associated methicillin-resistant S. aureus (CA-MRSA) and it's spreading into both community and the hospitals (1-3). Although several well-known CA-MRSA clones have shown the evidence of intercontinental spread, Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL)-positive ST30-MRSA-SCCmec type IV with spa type t019 is known to be the most successful pandemic clone (1). This clone has probably spread from Oceania toward Asia, Europe, and Americas (1), and has been widely found in the Philippines, Singapore, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Malaysia, and Japan (2, 4, 5). To date, however, this clone has not been found in Korea (2, 6). We report the first case of ST30-MRSA-IV infection in a Korean traveler returning from the Philippines.

A previously healthy 30-yr-old Korean woman presented with fever and painful swelling in her right buttock for 5 days in January 2012. The symptoms started the day after she had felt like insect-bite on her right buttock, while traveling in the Philippines. After coming back to Korea, she had taken cefaclor for four days without any improvement of buttock lesion. On admission, she had normal temperature (36.3℃), pulse rate of 110 beats/min, blood pressure of 114/72 mmHg, and respiratory rate of 20 breaths/min. Physical examination showed around 3 cm-sized carbuncle on her right buttock with spontaneously draining pus through a small central opening. Laboratory tests showed 8,340 leukocytes/µL, hemoglobin 13.9 g/dL, platelet 243,000/µL, and C-reactive protein (CRP) 0.03 mg/dL. Cefazolin was empirically started along with local curettage and irrigation. Culture of the aspirated pus grew MRSA. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing by minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) determination according to guidelines of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (7) showed that this MRSA strain was susceptible to gentamicin, ciprofloxacin, clindamycin, erythromycin, rifampicin, tetracycline, cotrimoxazole, and fusidic acid. MIC of vancomycin was 1 mg/L. Antibiotic regimen was changed to vancomycin and continued for 6 days with clinical improvement. She was cured after further use of oral clindamycin for 5 days.

An MRSA strain isolated from the patient was molecularly characterized and compared with the reference strains. Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) was carried out by PCR amplification and sequencing of seven housekeeping genes (arcC, aroE, glpF, gmk, pta, tpi, and yqiL) as previously described (8). The allelic profiles and sequence types (ST) were assigned by the MLST web site (http://saureus.mlst.net/). SCCmec types were determined by the multiplex PCR method (9). Presence of the lukF-PV and lukS-PV genes encoding the components of the PVL toxin was screened as previously described (10). The spa typing was performed as previously described (11). The spa type was determined by using Ridom SpaServer (http://spaserver2.ridom.de/saptypes.shtml). The isolate was determined to be PVL-positive ST30-MRSA-IV, and it belonged to spa type t019.

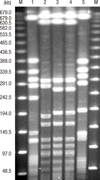

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) was performed as described previously (12). The PFGE patterns were analyzed using GelCompar II software (Applied Maths, Belgium), and compared to those of the ST30-MRSA-IV reference strains (P01-SAU-05-41 and P01-SAU-05-66; Asian Bacterial Bank, Asia Pacific Foundation for Infectious Diseases, Seoul, Korea), which had been previously collected from the Philippines by the Asian Network for Surveillance of Resistant Pathogens (ANSORP) for MRSA surveillance during the period from 2004 to 2006 (2), and the USA300 strain (NRS384), which had been obtained from the Network on Antimicrobial Resistance in Staphylococcus aureus (NARSA), supported under NIAID/NIH contract #HHSN2722 0070 0055C, and ST72-MRSA-IV strain (K01-SAU-04-1325; Asian Bacterial Bank, Asia Pacific Foundation for Infectious Diseases, Seoul, Korea) (Fig. 1). Analysis of the PFGE patterns showed that the isolate from the patient showed 83.3% similarity compared to those of the ST30-MRSA-IV reference strains collected from the Philippines.

Since emergence of CA-MRSA, intercontinental spread of those strains have contributed to a global spread of MRSA in the community (1), and increasing volumes of international travel and migration have facilitated it (13). Especially, a few clones including ST8-MRSA-IV (USA300), ST80-MRSA-IV, ST30-MRSA-IV, and ST59-MRSA-IV/V, have been the most successful pandemic CA-MRSA clones (1). A Swedish study, which analyzed imported cases of MRSA acquisition reported in Sweden during 2000 to 2003, revealed that the risks for MRSA acquisition during the travel differed across the countries and the risk was the highest in travelers returning from North Africa and followed by the Middle East, sub-Saharan Africa, Oceania, East Asia, South America, and North America (14).

The ST8 (USA300) or its closely related variants, which had been originated from the USA, at present are reported in many countries across five continents probably due to intercontinental transmission (13). Autochthonous acquisition of USA300 has also been documented in some countries including European countries, Canada, and Japan (13). The reports from various countries have suggested that ST80 clone has spread from Europe toward Asian countries, and the ST30 clone has spread from Oceania toward Asia, Europe and Americas (1). Additionally, ST59 clone has been widely found in Asian countries.

In Korea, ST72-MRSA-IV is known to be a major CA-MRSA clone and infections caused by this clone have been recently increasing in both community and the hospitals (2, 6). However, cases caused by well-known pandemic CA-MRSA clones have been very rarely reported. To date, only two cases caused by the ST8 (USA300) clone have been reported in Korea (15, 16). Although one Korean study with collection of 138 MRSA isolates from 2004 to 2005 found one isolate of PVL-negative ST30-MRSA, it belonged to t138 and SCCmec type was not provided (15). This is the first reported case of ST30-MRSA-IV infection in a Korean traveler returning from the Philippines. PVL-positive CA-MRSA isolate from our patient belonged to ST30 and t019, and carried SCCmec type IV. PFGE analysis showed that this strain was closely related to ST30-MRSA-IV reference strains, which had been previously collected from the Philippines. Such an intercontinental or inter-country spread of ST30-MRSA-IV strains from the Philippines has also been reported in European countries. The reports of ST30-MRSA-IV isolated in Denmark and the UK have shown that the majority of the strains had been imported from the Philippines (17, 18).

Frequent international travel and migration have increased the risk of international spread of CA-MRSA clones. The efforts to understand the changing epidemiology of CA-MRSA in each country and to prevent the international spread of the antibiotic-resistant pathogens should be continued. In addition, we should raise suspicion of CA-MRSA infection in travelers with skin and soft tissue infections returning from CA-MRSA-endemic countries.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) patterns of MRSA isolates from the patient and control strains. PFGE was performed with restriction enzyme SmaI. Lane 1, USA300 strain (NRS384) obtained from the Network on Antimicrobial Resistance in Staphylococcus aureus (NARSA); lane 2, isolate from the patient (K01-SAU-12-04); lane 3, P01-SAU-05-41 (CA-MRSA collection from the Philippines, ST30-MRSA-IV, t019, PVL-positive); lane 4, P01-SAU-05-66 (CA-MRSA collection from the Philippines, ST30-MRSA-IV, t2670, PVL-positive); lane 5, K01-SAU-04-1325 (ST72-MRSA-IV, t324); M, lambda marker. |

References

1. DeLeo FR, Otto M, Kreiswirth BN, Chambers HF. Community-associated meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet. 2010. 375:1557–1568.

2. Song JH, Hsueh PR, Chung DR, Ko KS, Kang CI, Peck KR, Yeom JS, Kim SW, Chang HH, Kim YS, et al. Spread of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus between the community and the hospitals in Asian countries: an ANSORP Study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011. 66:1061–1069.

3. Stefani S, Chung DR, Lindsay JA, Friedrich AW, Kearns AM, Westh H, Mackenzie FM. Meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA): global epidemiology and harmonisation of typing methods. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2012. 39:273–282.

4. Hsu LY, Koh YL, Chlebicka NL, Tan TY, Krishnan P, Lin RT, Tee N, Barkham T, Koh TH. Establishment of ST30 as the predominant clonal type among community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates in Singapore. J Clin Microbiol. 2006. 44:1090–1093.

5. Ma XX, Ito T, Chongtrakool P, Hiramatsu K. Predominance of clones carrying Panton-Valentine leukocidin genes among methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated in Japanese hospitals from 1979 to 1985. J Clin Microbiol. 2006. 44:4515–4527.

6. Kim ES, Song JS, Lee HJ, Choe PG, Park KH, Cho JH, Park WB, Kim SH, Bang JH, Kim DM, et al. A survey of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Korea. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007. 60:1108–1114.

7. Institutue CaLS. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing: twenty-first informational supplement: CLSI document M100-S21. 2011. Wayne: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institutue.

8. Enright MC, Day NP, Davies CE, Peacock SJ, Spratt BG. Multilocus sequence typing for characterization of methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible clones of Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Microbiol. 2000. 38:1008–1015.

9. Oliveira DC, de Lencastre H. Multiplex PCR strategy for rapid identification of structural types and variants of the mec element in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002. 46:2155–2161.

10. Lina G, Piémont Y, Godail-Gamot F, Bes M, Peter MO, Gauduchon V, Vandenesch F, Etienne J. Involvement of Panton-Valentine leukocidin-producing Staphylococcus aureus in primary skin infections and pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 1999. 29:1128–1132.

11. Harmsen D, Claus H, Witte W, Rothgänger J, Claus H, Turnwald D, Vogel U. Typing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a university hospital setting by using novel software for spa repeat determination and database management. J Clin Microbiol. 2003. 41:5442–5448.

12. Yinduo J. Methods in molecular biology: MRSA protocols. 2007. Totowa: Humana Press, Inc..

13. Nimmo GR. USA300 abroad: global spread of a virulent strain of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012. 18:725–734.

14. Stenhem M, Ortqvist A, Ringberg H, Larsson L, Olsson Liljequist B, Haeggman S, Kalin M, Ekdahl K. Imported methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Sweden. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010. 16:189–196.

15. Park C, Lee DG, Kim SW, Choi SM, Park SH, Chun HS, Choi JH, Yoo JH, Shin WS, Kang JH, et al. Predominance of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains carrying staphylococcal chromosome cassette mec type IVA in South Korea. J Clin Microbiol. 2007. 45:4021–4026.

16. Sohn KM, Chung DR, Baek JY, Kim SH, Joo EJ, Ha YE, Ko KS, Kang CI, Peck KR, Song JH. Post-influenza pneumonia caused by the USA300 community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2012. 27:313–316.

17. Bartels MD, Boye K, Rhod Larsen A, Skov R, Westh H. Rapid increase of genetically diverse methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Copenhagen, Denmark. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007. 13:1533–1540.

18. Orendi JM, Coetzee N, Ellington MJ, Boakes E, Cookson BD, Hardy KJ, Hawkey PM, Kearns AM. Community and nosocomial transmission of Panton-Valentine leucocidin-positive community-associated meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: implications for healthcare. J Hosp Infect. 2010. 75:258–264.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download