Abstract

Mixed autonomic hyperactivity disorder (MAHD) among patients with acquired brain injury can be rare. A delayed diagnosis of MAHD might exacerbate the clinical outcome and increase healthcare expenses with unnecessary testing. However, MAHD is still an underrecognized and evolving disease entity. A 25-yr-old woman was admitted the clinic due to craniopharyngioma. After an extensive tumor resection, she complained of sustained fever, papillary contraction, hiccup, lacrimation, and sighing. An extensive evaluation of the sustained fever was conducted. Finally, the cause for MAHD was suspected, and the patient was successfully treated with bromocriptine for a month.

Paroxysmal autonomic hyperactivity (PAH), first described by Penfield in 1929, is characterized by episodic hyperhidrosis, hypertension, hyperthermia, tachypnea, tachycardia, posturing, papillary dilatation and contraction, hiccups, and lacrimation (1). The range of these clinical features suggests autonomic hyperactivity of both the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems. However, many authors have described the autonomic hyperactivity as consistent with the sympathetic division alone (2, 3). Lately, cases of PAH have been separated into two categories: those consisting of paroxysmal sympathetic hyperactivity in the absence of parasympathetic features and those involving a combination of sympathetic and parasympathetic hyperactivity, termed mixed autonomic hyperactivity disorders (MAHD) (4, 5). MAHD is clinically diagnosed based on the combined presence of sympathetic hyperactivity (increased heart rate (HR), respiratory rate (RR), blood pressure (BP) and body temperature (BT), sweating and papillary dilatation) and parasympathetic hyperactivity (decreased HR, RR, BP and BT, piloerection, flushing, papillary contraction, hiccups, lacrimation, yawning, and sighing) (6).

Patients with PAH represent a significant additional burden on clinical practice (7, 8). However, a definite consensus on the diagnosis and pharmacological management of PAH has yet been established, because the available evidence for medical therapy is limited to only a few case reports.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case report describing MAHD following neurosurgical intervention due to craniopharyngioma that presented with intractable hyperthermia and has lately been controlled by bromocriptine.

A 25-yr-old woman arrived at the emergency department with drowsy consciousness and urinary incontinence on January 29, 2009. She had a severe headache and vomiting from 7 days prior to the visit, though she was previously in excellent health. The family and social histories were nonspecific.

On admission, her initial vital signs were as follows: BT 36.9℃, BP 130/80 mmHg, HR 120 beats/min, and RR 24 times/min. The patient presented with drowsy consciousness (Glasgow Coma Scale 12). The initial brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) scan showed a brain tumor in the suprasellar region with hydrocephalus (Fig. 1A, 2A). A preoperative hormone study including adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) 2.5 pg/mL, cortisol 2.5 µg/dL, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) 18.28 µIU/mL, free T4 1.06 ng/dL, prolactin 13.07 ng/mL, follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) 1.42 mIU/mL and human growth hormone 0.12 ng/mL reflected secondary adrenal insufficiency and subclinical hypothyroidism. Thus, she began on 25 mg synthyroxine and 15 mg prednisolone and tapered down to 5 mg for two months. On day 6 of hospital stay, she underwent a neurosurgical intervention following external ventricular drainage with intracranial pressure monitoring. A frontal craniotomy demonstrated a brain mass in the sellaturcica and the extended suprasellar cistern. Macroscopically, it showed cystic and solid components, necrotic debris, and fibrous tissue without calcification. An extensive tumor resection procedure was performed in an attempt to remove the cystic tumor-encasing optic nerves, and removal of both the hematoma and a total tumor lesion was conducted, followed by cranioplasty. Pathological examination of brain tissues confirmed craniopharyngioma. Post-operative MRI and CT scans showed complete resection of the craniopharyngioma (Fig. 1B, 2B). Unfortunately, she presented with gait disturbance, visual loss, and cognitive impairment (Glasgow Coma Scale 14 and Mini-Mental Status Examination 16/30) as postoperative complications. On day 9 of her hospital stay, she presented with polyuria and electrolytes imbalance: Na 168 mM/L, K 3.8 mM/L, and Cl 129 mM/L. She was subsequently diagnosed with diabetes insipidus and then received desmopressin acetate 60 mg/day, after which her electrolyte imbalance improved to Na 142 mM/L, K4.5 mM/L, Cl 108 mM/L. She underwent rehabilitation treatment.

On day 41 of her hospital stay, she developed sudden attacks of sustained high fever up to 39.6℃ in tympanic temperature all day long, accompanied by diaphoresis of the whole body including the face without pilar erection, pupillary contraction (pupil size isocoric 2 mm), hiccups, lacrimation, and sighing. Interestingly, she had no tachycardia, tachypnea, or hypertension during the attacks (Fig. 3), and changes of muscle tone including decerebrate or decorticate posturing, dystonia, rigidity and spasticity were not detected. She had kept an indwelling urinary catheter without bladder distension. She was alert and responded to simple questions appropriately with denial about any acute onset of discomfort or pain. Cranial nerve examination was also normal except for light perception with Glasgow Coma Scale 15 and Mini-Mental Status Examination 17/30. Results of a complete set of blood tests were normal, including white blood cell count (7,610/µL), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (2/µL), and C-reactive protein (2.981 mg/dL). An extensive work-up was conducted for the evaluation of fever of unknown origin. Repeated examinations for blood, sputum, and urine cultures were all negative. Serial brain CT scans could not detect any inflammatory foci, abscesses, hydrocephalus, or abnormal lesions in the brain stem (Fig. 2C). A three-phase bone scan and an inflammation scan (Gallium-67) did not detect any occult infectious or neoplastic processes. Electroencephalograms showed no definite ictal or interictal epileptic-form activity. She received a combined pituitary stimulation test during attacks of sustained hyperthermia. Postoperative hormone study upon taking 25 mg synthyroxine, 10 mg prednisolone and 60 mg desmopressin acetate was within normal limits: TSH 0.39 µIU/mL, free T4 0.85 ng/dL, ACTH 3.6 pg/mL, cortisol 10.1 µg/dL, prolactin 5.42 ng/mL, FSH 0.17 mIU/mL, human growth hormone 0.78 ng/mL. However, hyperthermia accompanying diaphoresis, papillary contraction, hiccups, lacrimation, and sighing continued.

Paroxysmal sustained hyperthermia lasted for 40 days and was resistant to conventional antipyretic therapy. Finally, she was diagnosed with MAHD accompanying a central fever on the basis of no identifiable foci after extensive work-ups for fever as well as her clinical settings in the post-neurosurgical state. On the 41st febrile day, chlorpromazine (25 mg per 8 hr) was started, but she showed sustained hyperthermia and even focal seizures on the second day of the medication as a potential adverse event of chlorpromazine. She was alternatively given bromocriptine with an initial dose of 0.05 mg/kg every 8 hr. The episode of paroxysmal hyperthermia and accompanying manifestations were improved dramatically on the third day of bromocriptine. Also accompanying symptoms including diaphoresis, papillary contraction, hiccups, lacrimation, and sighing were dramatically improved. During the following clinical course, she developed a fever up to 38.0℃ again on the 4th and 16th day of the medication, and bromocriptine was increased to 0.05 mg/kg every 6 hr and 0.05 mg/kg every 5 hr, respectively. Bromocriptine was discontinued with clinical improvement after a total administration time of 32 days. Her symptoms and signs associated with MAHD were fully recovered without relapse. Examinations at the outpatient clinic showed that she was doing well for the following 4 months.

In the present case, diagnosis of MAHD was based on mixed autonomic hyperactivity that developed 54 days after neurosurgical intervention for craniopharyngioma and was characterized by hyperthermia, diaphoresis, papillary contraction, hiccups, lacrimation, and sighing. An extensive work-up for fever also excluded other possible causes of the fever. Unfortunately, her diagnosis was delayed for 40 days because her symptoms were not immediately recognized as MAHD, but the administration of bromocriptine successfully controlled her overactive autonomic tone.

Of patients admitted to the neurological intensive care unit (ICU), 23%-47% develop fever (9-11). Although the most common causes of their fever are infections (up to 50%), the cause of fever often remains unexplained (9, 12). In the previous reports, the incidence of central fever varies from 4% to 33% (2, 7, 13). Especially in the cases of MAHD, this may have been underestimated because the precise clinical definition of the disease is still evolving (1, 14).

Episodes of PAH can be seen in association with diverse neurological diseases. In our case, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, malignant hyperthermia, the Cushing response, sepsis, encephalitis, drug fever, and hydrocephalus were all ruled out. PAH usually occurs 5 to 7 days after the brain injury. Our case presented with this syndrome 54 days after neurosurgical intervention, which is consistent with a previous report (8).

The current literature provides little consensus on how to choose an initial therapy for PAH or MAHD. The central autonomic activity is regulated in the hypothalamus that control specific subsets of the preganglionic sympathetic and parasympathetic pathway (15). Therefore, the mechanism of MAHD can be associated with injury of the hypothalamus. Two disconnection theories suggest that the autonomic dysfunction follows a structural disconnection resulting from an increased intracerebral pressure or a functional disconnection resulting from a neurotransmitter blockade. One theory demonstrates that paroxysm is driven by the excitatory center located in the diencephalon, and the other suggests that the causative diencephalic centers are more inhibitory, with paroxysm driven by excitatory spinal cord processes (14). This provides a rationale for the observed bromocriptine effects. Bromocriptine, a dopamine D2 agonist, acts at the level of the hypothalamus and the corpus striatum and has been reported to help control PAH, which is caused by a dopamine blockade, as reported in previously published cases (16-19).

In conclusion, this is the first case report of MAHD after neurosurgery controlled totally with bromocriptine treatment. Our report indicates that MAHD should be considered as a possible diagnosis among patients with sustained fever of unknown origin after brain injury to evade unnecessary examinations and to administer a timely treatment.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings of the brain. (A) The MRI on admission shows a heterogeneously enhancing, partially calcified mass in the suprasellar region with obstructive hydrocephalus and hematoma fluid level. (B) The post-operative follow-up MRI taken on the 21st day after craniotomy shows no residual solid tumor but multiple, small, intracranial hemorrhages, in the frontal and the right thalamus.

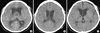

Fig. 2

Computed tomography (CT) findings of the brain. (A) Suprasellar mixed density and hydrocephalus were showed in the pre-operational CT. (B) Hydrocephalus decreased and intra-ventricular hemorrhage was revealed in the post-operation CT. (C) Subdural effusion over the left frontal convexity was demonstrated, but there were no residual tumors or infection foci.

References

1. Penfiel W. Diencephalic autonomic epilepsy. Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 1929. 22:358–374.

2. Rabinstein AA. Paroxysmal sympathetic hyperactivity in the neurological intensive care unit. Neurol Res. 2007. 29:680–682.

3. Boeve BF, Wijdicks EF, Benarroch EE, Schmidt KD. Paroxysmal sympathetic storms ("diencephalic seizures") after severe diffuse axonal head injury. Mayo Clin Proc. 1998. 73:148–152.

4. Fox RH, Wilkins DC, Bell JA, Bradley RD, Browse NL, Cranston WI, Foley TH, Gilby ED, Hebden A, Jenkins BS, et al. Spontaneous periodic hypothermia: diencephalic epilepsy. Br Med J. 1973. 2:693–695.

5. Giroud M, Sautreaux JL, Thierry A, Dumas R. Diencephalic epilepsy with congenital suprasellar arachnoid cyst in an infant. Childs Nerv Syst. 1988. 4:252–254.

6. Perkes I, Baguley IJ, Nott MT, Menon DK. A review of paroxysmal sympathetichyperactivity after acquired brain injury. Ann Neurol. 2010. 68:126–135.

7. Fernández-Ortega JF, Prieto-Palomino MA, Muñoz-López A, Lebron-Gallardo M, Cabrera-Ortiz H, Quesada-García G. Prognostic influence and computed tomography findings in dysautonomic crises after traumatic brain injury. J Trauma. 2006. 61:1129–1133.

8. Baguley IJ, Nicholls JL, Felmingham KL, Crooks J, Gurka JA, Wade LD. Dysautonomia after traumatic brain injury: a forgotten syndrome? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999. 67:39–43.

9. Commichau C, Scarmeas N, Mayer SA. Risk factors for fever in the neurologic intensive care unit. Neurology. 2003. 60:837–841.

10. Kilpatrick MM, Lowry DW, Firlik AD, Yonas H, Marion DW. Hyperthermia in the neurosurgical intensive care unit. Neurosurgery. 2000. 47:850–855.

11. Stocchetti N, Rossi S, Zanier ER, Colombo A, Beretta L, Citerio G. Pyrexia in head-injured patients admitted to intensive care. Intensive Care Med. 2002. 28:1555–1562.

12. Rabinstein AA, Sandhu K. Non-infectious fever in the neurological intensive care unit: incidence, causes and predictors. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007. 78:1278–1280.

13. von Wild KR. Hannover, Münster TBI Study Council. Posttraumatic rehabilitation and one year outcome following acute traumatic brain injury (TBI): data from the well defined population based German Prospective Study 2000-2002. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2008. 101:55–60.

14. Baguley IJ. Autonomic complications following central nervous system injury. Semin Neurol. 2008. 28:716–725.

15. Benarroch EE. The central autonomic network: functional organization, dysfunction, and perspective. Mayo Clin Proc. 1993. 68:988–1001.

16. Blackman JA, Patrick PD, Buck ML, Rust RS Jr. Paroxysmal autonomic instability with dystonia after brain injury. Arch Neurol. 2004. 61:321–328.

17. Bullard DE. Diencephalic seizures: responsiveness to bromocriptine and morphine. Ann Neurol. 1987. 21:609–611.

18. Rossitch E Jr, Bullard DE. The autonomic dysfunction syndrome: aetiology and treatment. Br J Neurosurg. 1988. 2:471–478.

19. Russo RN, O'Flaherty S. Bromocriptine for the management of autonomic dysfunction after severe traumatic brain injury. J Paediatr Child Health. 2000. 36:283–285.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download