Abstract

Lysinuric protein intolerance (LPI) is a rare inherited metabolic disease, caused by defective transport of dibasic amino acids. Failure to thrive, hepatosplenomegaly, hematological abnormalities, and hyperammonemic crisis are major clinical features. However, there has been no reported Korean patient with LPI as of yet. We recently encountered a 3.7-yr-old Korean girl with LPI and the diagnosis was confirmed by amino acid analyses and the SLC7A7 gene analysis. Her initial chief complaint was short stature below the 3rd percentile and increased somnolence for several months. Hepatosplenomegaly was noted, as were anemia, leukopenia, elevated levels of ferritin and lactate dehydrogenase, and hyperammonemia. Lysine, arginine, and ornithine levels were low in plasma and high in urine. The patient was a homozygote with a splicing site mutation of IVS4+1G > A in the SLC7A7. With the implementation of a low protein diet, sodium benzoate, citrulline and L-carnitine supplementation, anemia, hyperferritinemia, and hyperammonemia were improved, and normal growth velocity was observed.

Lysinuric protein intolerance (LPI; MIM 222700) is a rare inherited metabolic disorder of dibasic amino acid transport. Renal tubular and intestinal transport is deficient, resulting in decreased circulating dibasic amino acid levels. Hyperammonemia is caused by a lack of sufficient ornithine to support activity of ornithine transcarbamylase in the urea cycle (1). Typically, LPI can present with variable symptoms and signs including recurrent vomiting and episodes of diarrhea as well as altered mental status due to hyperammonemia and hepatosplenomegaly. Over time, chronic complications may occur such as growth failure, osteoporosis, pulmonary alveolar proteinosis, progressive glomerular and tubular diseases, and hematologic abnormalities including erythroblastophagocytosis resembling the hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) (2).

The SLC7A7 gene is the only gene in which mutations are currently known to cause LPI. LPI was first reported in the Finnish population in 1965 (3), and more than 150 patients with approximately 50 different SLC7A7 mutations have been observed worldwide to date (2). However, nearly half of reported patients were Finnish while the other patients of non-Finnish origin were homozygous for a private mutation (1, 4, 5). There has been no report of LPI patients in Korea yet.

Recently, we examined a Korean girl with LPI, who presented with short stature and hyperammonemia and was diagnosed by biochemical assays and genetic analysis of the SLC7A7 gene. We describe our observations of this patient with a brief review of the literature.

A 3.7-yr-old Korean girl visited Seoul National University Children's Hospital with the chief complaint of short stature and increased somnolence for several months at March 11th, 2011. She was born with a birth weight of 3.38 kg at 38+6 weeks of gestation and was the first child born to healthy and non-consanguineous parents. She had a history of acute gastroenteritis with diarrhea and was managed with intravenous hydration at several different times. However, there had been no event of acute metabolic crisis including altered consciousness in her past medical history. The patient was able to walk independently at the age of 14 months, and spoke words with meaning at the age of 12 months. She had no evidence of significant neurodevelopmental delay.

Patient height was 89.9 cm (< 3th percentile), weight was 14.2 kg (25 percentile), and her head circumference was 50.5 cm (50-75th percentile). The calculated mid-parental height referred to as the genetic target height was 155 cm (10-25th percentile). Her bone age was 3 yr old. The slightly protruded abdomen was noted and the liver was palpable at 5 cm width below the subcostal margin as per the findings from the physical examination. No gastrointestinal symptoms were observed. Breathing sound was clear and no skin lesion was visible. Although the patient complained of increased somnolence, no abnormal neurological signs including disorientation were found through the neurological examination.

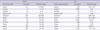

Laboratory findings showed microcytic hypochromic anemia (hemoglobin: 9.4 g/dL), leukopenia (WBC: 3,600/µL, absolute neutrophil count: 1,189/µL), elevated liver enzyme (AST/ALT: 154/60 IU/L), hypoproteinemia (total protein: 6.1 g/dL, albumin: 3.6 g/dL), in addition to elevated ferritin (1,689.5 ng/mL) and lactate dehydrogenase (1,133 IU/L) concentrations, and hyperammonemia (520 µM). Serum iron concentration and coagulation profiles were normal. Serum fibrinogen level was in the lower part of normal range (175 mg/dL). Lipid profiles showed normal cholesterol and triglycerides levels. Serum electrolytes, phosphorus, uric acid, and alkaline phosphatase levels were also normal. Spot urine protein to creatinine ratios were repetitively elevated ranging from 0.3 to 0.8, though overt albuminuria was absent and serum creatinine levels were normal. We checked 24 hr urine beta-2-microglobulin (1.88 µg/mL) and urine N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminidase to creatinine ratio (49.1 IU/g Cr) for assessing renal tubular function, and these two values were above the normal ranges. The results of plasma and urine amino acid analyses at diagnosis were shown in Table 1. Distinctively, lysine, arginine, and ornithine levels were in the lower ends of normal ranges. Also, serine, glycine, citrulline, alanine and glutamine concentrations were slightly elevated in plasma amino acid analysis. Orotic acid excretion was not increased in urine organic acid analysis, but excretion of lysine, arginine, and ornithine was markedly elevated in urine amino acid analysis.

The patient was a homozygote with a known mutation IVS4+ 1G > A, causing exon 4 skipping. Her parents and younger brother were heterozygous carriers of this mutation (Fig. 1). On the findings of radiological evaluation, hepatosplenomegaly with 8.5 cm diameter of the spleen was identified, but no focal parenchymal lesion in the abdominal organs was observed. Simple radiographs showed normal findings of the lungs, and osteopenia of the spine was not observed.

For acute management of hyperammonemia, oral arginine supplementation and intravenous sodium benzoate infusion were initiated. Solutions of 10% glucose and 20% lipid emulsion were administered intravenously for adequate energy supply. After the level of ammonia was normalized and the diagnosis of LPI was confirmed, low protein diet (1.5 g/kg/day) and oral supplementation of sodium benzoate (200 mg/kg/day), citrulline (100 mg/kg/day) and L-carnitine (50 mg/kg/day) have been maintained. During the follow-up period of 12 months, acute episode of metabolic derangement was absent, and anemia and leukopenia were resolved. Serum ferritin had decreased and ammonia levels stayed within the normal range. She is 4.7 yr-old now and shows normal growth velocity (7.0 cm/yr).

LPI is an inborn error of metabolism caused by mutations of the SLC7A7 gene located in chromosome 14q11.2, encoding the light subunit of the heteromeric amino acid transporter system y+L. This system mediates the transport of dibasic amino acids including lysine, ornithine, and arginine at the basolateral membrane of epithelial cells in the renal tubule and small intestine. Most of the clinical findings of LPI may be related to the metabolic abnormality originating from altered absorption and reabsorption of dibasic amino acids (1, 2).

Molecular genetic testing identifies disease-causing mutations in more than 95% of patients with typical biochemical findings of LPI (6). The founder effects of some mutations can be observed, such as IVS6-2A > T in Finnish, c.1625_1626insATCA in Italian, and p.Arg410X in Japanese (7-9). But, a genotype-phenotype correlation has not been established. The same genotype may give rise to extensive clinical variability even in the same family (6). Our patient has a homozygous mutation of IVS4+1G > A, causing a skipping of exon 4. The patient's younger brother and parents were heterozygous carriers of this mutation. IVS4+1G > A is previously reported in Japanese patients (7, 10), and also was found in a Turkish patient (6). Among them, clinical features were described in only one Japanese patient, who was a compound heterozygote with mutations IVS4+1G > A and IVS7+1G > T. This patient was presented with hepatosplenomegaly, hyperammonemia and seizures at the age of 10 yr. However, mental development was normal and no chronic complications had been observed (7). In our patient, the age at diagnosis was 3.7 yr, and short stature and increased somnolence were the only subjective symptoms with regards to the diagnosis for LPI. However, her physical and laboratory findings demonstrated hepatosplenomegaly, hyperammonemia, and hematological abnormalities.

Hematological manifestations are frequently found to range from mild normochromic or hypochromic anemia to leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, and erythroblastophagocytosis upon bone marrow examination. These findings usually do not cause subjective symptoms, though overt HLH has been observed in some LPI patients (11). Although our patient did not fulfill all of the criteria for diagnosis for HLH (12), she showed some features of HLH such as splenomegaly, hyperferritinemia, mild anemia and leukopenia, and lower normal levels of fibrinogen at diagnosis.

Proteinuria and microscopic hematuria are frequently observed, and membranous or mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis and Fanconi syndrome have been reported in LPI patients (13). Although the long-term renal outcome had been poorly understood thus far, about 10% of LPI patients suffered from end-stage renal disease requiring hemodialysis (13). Our patient did not show proteinuria or hematuria on routine urine examinations, but tubular dysfunction was suggested from the findings of increased urine beta-2-microglobulin excretion and N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminidase to creatinine.

In acute hyperammonemic crises, intravenous administration of arginine and nitrogen scavenger drugs including sodium benzoate and sodium phenylpyruvate is necessary to lower ammonia levels (14). A low-protein diet with oral supplementation of citrulline, nitrogen scavenger drugs and carnitine is a mainstay of long term therapy (2, 15). Citrulline is a neutral amino acid and is absorbed by a different transport system from that of dibasic amino acids, but once into the cell it is converted via arginine to ornithine and enhances the urea cycle function (16). Our patient also showed clinical and biochemical improvement with nutritional management. Therefore monitoring of plasma ammonia, amino acid and urine orotic acid concentrations, and life-long careful surveillance of multi-organ complications are necessary for each LPI patient after diagnosis (2).

Here, we report a child with typical manifestations of LPI for the first time in Korea. LPI is a multi-systemic disease, and the phenotypic variability of LPI could result in delayed diagnosis or misdiagnosis. LPI should be considered for differential diagnosis of hyperammonemia.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Palacín M, Bertran J, Chillarón J, Estévez R, Zorzano A. Lysinuric protein intolerance: mechanisms of pathophysiology. Mol Genet Metab. 2004. 81:S27–S37.

2. Sebastio G, Sperandeo MP, Andria G. Lysinuric protein intolerance: reviewing concepts on a multisystem disease. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2011. 157:54–62.

3. Perheentupa J, Visakorpi JK. Protein intolerance with deficient transport of basic aminoacids. Another inborn error of metabolism. Lancet. 1965. 2:813–816.

4. Palacín M, Borsani G, Sebastio G. The molecular bases of cystinuria and lysinuric protein intolerance. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2001. 11:328–335.

5. Sperandeo MP, Andria G, Sebastio G. Lysinuric protein intolerance: update and extended mutation analysis of the SLC7A7 gene. Hum Mutat. 2008. 29:14–21.

6. Mykkänen J, Torrents D, Pineda M, Camps M, Yoldi ME, Horelli-Kuitunen N, Huoponen K, Heinonen M, Oksanen J, Simell O, et al. Functional analysis of novel mutations in y(+)LAT-1 amino acid transporter gene causing lysinuric protein intolerance (LPI). Hum Mol Genet. 2000. 9:431–438.

7. Sperandeo MP, Bassi MT, Riboni M, Parenti G, Buoninconti A, Manzoni M, Incerti B, Larocca MR, Di Rocco M, Strisciuglio P, et al. Structure of the SLC7A7 gene and mutational analysis of patients affected by lysinuric protein intolerance. Am J Hum Genet. 2000. 66:92–99.

8. Koizumi A, Shoji Y, Nozaki J, Noguchi A, E X, Dakeishi M, Ohura T, Tsuyoshi K, Yasuhiko W, Manabe M, et al. A cluster of lysinuric protein intolerance (LPI) patients in a northern part of Iwate, Japan due to a founder effect. The Mass Screening Group. Hum Mutat. 2000. 16:270–271.

9. Tringham M, Kurko J, Tanner L, Tuikkala J, Nevalainen OS, Niinikoski H, Näntö-Salonen K, Hietala M, Simell O, Mykkänen J. Exploring the transcriptomic variation caused by the Finnish founder mutation of lysinuric protein intolerance (LPI). Mol Genet Metab. 2012. 105:408–415.

10. Noguchi A, Shoji Y, Koizumi A, Takahashi T, Matsumori M, Kayo T, Ohata T, Wada Y, Yoshimura I, Maisawa S, et al. SLC7A7 genomic structure and novel variants in three Japanese lysinuric protein intolerance families. Hum Mutat. 2000. 15:367–372.

11. Gordon WC, Gibson B, Leach MT, Robinson P. Haemophagocytosis by myeloid precursors in lysinuric protein intolerance. Br J Haematol. 2007. 138:1.

12. Henter JI, Horne A, Aricó M, Egeler RM, Filipovich AH, Imashuku S, Ladisch S, McClain K, Webb D, Winiarski J, et al. HLH-2004: Diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007. 48:124–131.

13. Tanner LM, Näntö-Salonen K, Niinikoski H, Jahnukainen T, Keskinen P, Saha H, Kananen K, Helanterä A, Metso M, Linnanvuo M, et al. Nephropathy advancing to end-stage renal disease: a novel complication of lysinuric protein intolerance. J Pediatr. 2007. 150:631–634.

14. Simell O, Sipilä I, Rajantie J, Valle DL, Brusilow SW. Waste nitrogen excretion via amino acid acylation: benzoate and phenylacetate in lysinuric protein intolerance. Pediatr Res. 1986. 20:1117–1121.

15. Tanner LM, Näntö-Salonen K, Venetoklis J, Kotilainen S, Niinikoski H, Huoponen K, Simell O. Nutrient intake in lysinuric protein intolerance. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2007. 30:716–721.

16. Botschner J, Smith DW, Simell O, Scriver CR. Comparison of ornithine metabolism in hyperornithinaemia-hyperammonaemia-homocitrullinuria syndrome, lysinuric protein intolerance and gyrate atrophy fibroblasts. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1989. 12:33–40.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download