Abstract

The distinction of a spitz nevus from a melanoma can be difficult and in some cases, impossible. A misdiagnosed spitz nevus can metastasize and lead to fatal outcomes, especially in children. A 5-yr-old girl presented with a 1-yr history of a solitary pinkish nodule on her left hand. On physical examination, she had a palpable left axillary lymph node. We performed biopsy and checked 3 sentinel lymph nodes (SLN) on her axillary area. The biopsy specimen showed multiple variably sized and shaped nests with large spindle or polygonal cells and SLN biopsy showed 3 of 3 lymph nodes that were metastasized. Under the diagnosis of spitzoid melanoma, she was treated with excision biopsy and complete left axillary lymph nodes were dissected. She received interferon-α2b subcutaneously at a dose of 8 MIU per day, 3 times weekly for 12 months, and shows no recurrence.

Spitzoid melanoma is a malignant melanoma occurring commonly on the head and extremities and shares many histopathologic and clinical features with spitz nevus (1-3). Relative lack of reliable pathological criteria for discrimination between benign and malignant melanocytic lesions makes it very difficult for clinicians and pathologists to render the ominous diagnosis of melanoma, especially combined with the low frequency of cutanoeous melanoma in childhood. Cutaneous melanoma in children and adolescents (age 0-17 yr) accounted for only 1.3% of cases in the USA over the past two decades and only 0.3%-0.4% of melanomas are diagnosed for patients younger than 10 yr (3).

Clinically, spitzoid melanomas are usually changing amelanotic nodular lesions which can be crusted and ulcerated. They resemble hemangiomas, pyogenic granulomas, xanthograulomas, or basal cell carcinomas (1). Although spitzoid melanomas are more common in adults, due to extremely low rates of other cutaneous melanoma subtypes in children under the age of 17 yr, the incidence rate appears disproportionately higher in this age group (1, 4, 5). Consequently, there often are spitzoid melanomas originally diagnosed as spitz nevi that metastasize and lead to fatal outcomes in children (6).

In the Korean literature, there are no previously reported cases of spitzoid melanoma with lymph node metastasis in children. Herein, we report a rare case of spitzoid melanoma in a 5-yr-old Korean girl along with the interest on its lymph node metastasis.

On June 15, 2009, a 5-yr-old girl presented with a 1-yr history of a slightly tender, solitary pinkish protruding nodule on the dorsum of her left hand. The nodule dimensions were 7 × 9 mm (Fig. 1) and it would bleed easily with a light touch. Under the impression of pyogenic granuloma or spitz nevus, we took punch biopy. The histopathologic findings showed multiple nests of variable size and irregular shape with large spindle or polygonal cells which had amphophilic cytoplasm. Contrary to features of a spitz nevus, there were no mature cells from the surface to the base and common mitosis in the dermis was observed. The Breslow's depth was obviously over 4 mm (Fig. 2). The immunohistochemical staining showed that Melan-A was positive in whole skin level and weakly positive for HMB-45 (Fig. 3). On the basis of these clinical and histological findings, a diagnosis of spitzoid melanoma was made. There was no personal or family history of melanomas and the patient was otherwise in good health.

On physical examination, the patient had a palpable left axillary lymph node. The laboratory analysis revealed the patient had 442 IU/L of LDH levels in her blood which was within the high normal range (50-450 IU/L). Gene analysis using multiplex PCR showed negative for B-RAF somatic mutation. Since a palpable left axillary lymph node was present, a metastatic workup by chest computed tomography (CT) and positron emission tomography/CT (PET/CT) scan was also performed. However, in these evaluations, there were no specific signs of distant metastasis. We performed excision biopsy with 2 cm free margin and repaired the defect with a full thickness skin graft. We checked 3 sentinel lymph nodes on her left axillary area and found that all of them were metastasized. In cooperation with the breast surgeons, complete left axillary lymph nodes were dissected, which showed one of eighteen lymph nodes to be positive (Fig. 4). She received interferon-α2b subcutaneously at a dose of 8 MIU per day, 3 times weekly for 12 months. She shows no recurrence until now, 27 months after surgery.

Pediatric melanoma is somewhat different from adult melanoma. It is more likely to have an atypical clinical appearance such as amelanotic or pyogenic granuloma-like, like in the present case. The nodular subtype is more common in pediatric melanoma than adult melanoma (27% vs 15%) and tends to be thicker and more frequently metastasizes to sentinel lymph nodes (SLN) (7).

In comparison with spitz nevus, spitzoid melanoma has an asymmetric shape with a size usually exceeding 10 mm. Histologically, it showed nests of variable size and shape with large spindle or epithelioid cells. Cytologically, the melanocytes have large, pleomorphic, hyperchromatic nuclei and prominent basophilic to eosinophilic nucleoli. Spitzoid melanoma has a higher degree of cytologic atypia than spitz nevus (2).

However, in most cases, these features are not helpful to distinguish spitzoid melanoma from spitz nevus and therefore, recently there are studies that are trying to use molecular cytogenetic analysis for distinction. Bastian et al. (8, 9) demonstrated that 80% of spitz nevi with gain of chromosome 11p showed increased copy number of an oncogenic HRAS allele. HRAS is rarely mutated in malignant melanoma (1, 8, 9). Though the detection of B-RAF gene mutation was recently studied, Lee et al. (6) have suggested that in contrast to the majority of cutaneous melanomas, activating hot-spot mutations in B-RAF or N-RAS were not involved in the pathogenesis of spitzoid melanoma. In our case, the mutation of B-RAF gene was negative.

In studies using immunohistochemistry, Ki-67/MIB-1 proliferation index was suggested as a useful marker for distinguishing spitz nevus from melanoma. Bergman et al. (10) reported that the best cutoff value for discriminating was 4.5% in a total count of Ki-67/MIB-1 stained epidermal and dermal melanocytes. Other study results indicated that the index more than 10% favors melanoma and less than 2%, spitz nevus. The index between 2% and 10% yields various predictive values for spitz nevus (11). The Ki-67 proliferation index of the present patient was 5%. Although this proliferation index is low value, it is sufficient to meet the cutoff value for melanoma as mentioned by Bergman.

Though the place of SLN biopsy in the management of atypical spitzoid melanocytic lesions remains uncertain (4), it may serve as an adjunct procedure in the evaluation of diagnostically difficult spitzoid tumors by increasing the sensitivity of the diagnosis and providing potentially useful prognostic information (3). Several studies reported that SLN biopsy is recommended for prognostic purposes when malignant melanoma cannot be entirely ruled out in such cases as 1 mm or more in Breslow thickness and Clark IV or ulcerated lesion even if thinner than 1 mm (1, 12). However, this needs to be further investigated because another study revealed that there were no significant differences between SLN-positive and SLN-negative cases with regards to histological features (3). One problem is that there is another group of spitz tumors that have the potential of spreading to a regional node, but lack the potential for distant metastasis. Also, the benign lesion (spitz nevus cell aggregate of lymph node) looks more like a melanoma metastasis than the better-known nevus cell aggregate of the lymph node (13). In addition, some pathologists have cautioned against classifying cutaneous melanocytic tumors based on SLN results (14). They point out that a lymph node may contain benign tissue foreign to it, such as mesothelial cells, mammary epithelium, or Mullerian epithelium. Such "benign metastases" have also been suggested to explain the occurrence of many nodal melanocytic nevi (14). Therefore, Busam et al. (15) suggested that if uncertain about the correct diagnosis, further investigation by comparative genomic hybridization or fluorescence in situ hybridization studies before SLN biopsy is recommended. With regard to our patient, histopathologic and immunohistochemical findings suggested strongly for malignant melanoma and axillary lymph nodes were palpable, so we performed SLN biopsy and complete lymph node dissection. Totally, 4 of the 21 harvested lymph nodes showed atypical melanocytes within the lymph node parenchyma, which implied metastatic malignant melanoma.

Pol-Rodriguez et al. (5) found 88% 5-yr survival rate in children with metastatic spitzoid melanoma between 0 and 10 yr of age compared with 49% in those between 11 and 17 yr of age. There are recent studies demonstrating that the prognosis of children with spitzoid melanoma has been suggested to be better than observed in adults, even when they have local metastases or positive SLNs (1, 13, 14). Though it may at least in part reflect the strength of the immune system at a young age, this remains controversial (3, 14). It has also been suggested that surgical intervention (removal of the positive SLNs) alters the biologic behavior of the tumor and thereby permits a more favorable clinical course (14).

In conclusion, this is a rare case of a 5-yr-old child diagnosed with metastatic spitzoid melanoma, stage IV (M1a), and there has not been any previously reported case in Korean literature. The 5-yr survival rate of stage IV (M1a) in conventional cutaneous melanoma is 18.8%, but it may be higher in this patient as we discussed above. We will follow her up closely for signs of regional and distant recurrence.

Figures and Tables

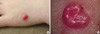

Fig. 1

Gross view of the skin lesion. (A) Slightly tender, solitary pinkish protruding nodule on the lateral side of the dorsum of her left hand. (B) Dermoscopic photo of lesion.

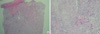

Fig. 2

Histopathology of the skin lesion. (A) Abundant irregular nests of different sizes and shapes and asymmetrical proliferation of enlarged atypical epithelioid and spindle shaped melanocytes in the deep dermis. No maturation of cells from near the surface to the base (H&E stain, × 40). (B) At high power magnification, atypical epithelioid and spindle shaped melanocytes with large, hyperchromatic, pleomorphic nuclei were observed (H&E stain, × 100).

References

1. Kamino H. Spitzoid melanoma. Clin Dermatol. 2009. 27:545–555.

2. Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Murphy GF, Xu X. Elder D, Elenitsas R, Johnson BL, Murphy GF, Xu X, editors. Benign pigmented lesions and malignant melanoma. Lever's histopathology of the skin. 2009. 10th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;718–724.

3. Paradela S, Fonseca E, Pita S, Kantrow SM, Goncharuk VN, Diwan H, Prieto VG. Spitzoid melanoma in children: clinicopathological study and application of immunohistochemistry as an adjunct diagnostic tool. J Cutan Pathol. 2009. 36:740–752.

4. Barnhill RL, Gupta K. Unusual variants of malignant melanoma. Clin Dermatol. 2009. 27:564–587.

5. Pol-Rodriquez M, Lee S, Silvers DN, Celebi JT. Influence of age on survival in childhood spitzoid melanomas. Cancer. 2007. 109:1579–1583.

6. Lee DA, Cohen JA, Twaddell WS, Palacios G, Gill M, Levit E, Halperin AJ, Mones J, Busam KJ, Silvers DN, Celebi JT. Are all melanomas the same? Spitzoid melanoma is a distinct subtype of melanoma. Cancer. 2006. 106:907–913.

7. Berk DR, LaBuz E, Dadras SS, Johnson DL, Swetter SM. Melanoma and melanocytic tumors of uncertain malignant potential in children, adolescents and young adults: the Stanford experience 1995-2008. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010. 27:244–254.

8. Bastian BC, Wesselman U, Pinkel D, Leboit PE. Molecular cytogenetic analysis of Spitz nevi shows clear differences to melanoma. J Invest Dermatol. 1999. 113:1065–1069.

9. Bastian BC, LeBoit PE, Pinkel D. Mutations and copy number increases of HRAS in Spitz nevi with distinctive histopathological features. Am J Pathol. 2000. 157:967–972.

10. Bergman R, Malkin L, Sabo E, Kerner H. MIB-1 monoclonal antibody to determine proliferative activity of Ki-67 antigen as an adjunct to the histopathologic differential diagnosis of Spitz nevi. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001. 44:500–504.

11. Vollmer RT. Use of Bayes rule and MIB-1 proliferation index to discriminate Spitz nevus from malignant melanoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004. 122:499–505.

12. Murali R, Sharma RN, Thompson JF, Stretch JR, Lee CS, McCarthy SW, Scolyer RA. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in histologically ambiguous melanocytic tumors with spitzoid features (so-called atypical spitzoid tumors). Ann Surg Oncol. 2008. 15:302–309.

13. Mooi WJ, Krausz T. Spitz nevus versus spitzoid melanoma: diagnostic difficulties, conceptual controversies. Adv Anat Pathol. 2006. 13:147–156.

14. Busam KJ, Murali R, Pulitzer M, McCarthy SW, Thompson JF, Shaw HM, Brady MS, Coit DG, Dusza S, Wilmott J, Kayton M, Laquaglia M, Scolyer RA. Atypical spitzoid melanocytic tumors with positive sentinel lymph nodes in children and teenagers, and comparison with histologically unambiguous and lethal melanomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009. 33:1386–1395.

15. Busam KJ, Pulitzer M. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for patients with diagnostically controversial Spitzoid melanocytic tumors? Adv Anat Pathol. 2008. 15:253–262.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download