Abstract

Temozolomide is an oral alkylating agent with clinical activity against glioblastoma multiforme (GM). It is generally well-tolerated and has few pulmonary side effects. We report a case of temozolomide-associated brochiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia (BOOP) requiring very high-dose corticosteroid treatment. A 56-yr-old woman presented with a 2-week history of exertional dyspnea. For the treatment of GM diagnosed 4 months previously, she had undergone surgery followed by chemoradiotherapy, and then planned adjuvant chemotherapy with temozolomide. After the 1st cycle, progressive dyspnea was gradually developed. Chest radiograph showed diffuse patchy peribronchovascular ground-glass opacities in both lungs. Conventional dose of methylprednisolone (1 mg/kg/day) was begun for the possibility of BOOP. Although transbronchial lung biopsy findings were compatible with BOOP, the patient's clinical course was more aggravated until hospital day 5. After the dose of methylprednisolone was increased (500 mg/day for 5 days) radiologic findings were improved dramatically.

Several medications are associated with organizing pneumonia, and bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia (BOOP) (1). Because the BOOP represents an inflammatory response of the lung, it can be generally reversed by causative drug cessation and/or corticosteroid therapy. Temozolomide is a new alkylating agent with clinical activity against glioblastoma multiforme. It is a generally well-tolerated oral agent with mild pulmonary side effects. In a phase II trial for patients with recurrent or progressive brain metastases from a variety of solid tumors, grade 3 pneumonitis was developed in two cases (2), and there has been only one report of temozolomide-associated organizing pneumonitis until now (3). We herein report a case of temozolomide-associated BOOP that required very high-dose corticosteroid treatment.

A 56-yr-old woman presented with a 2-week history of dyspnea. After being diagnosed 4 months before presentation as having glioblastoma multiforme, the patient had undergone craniectomy and tumor removal followed by radiotherapy (180 cGy, 33 fractions) combined with low-dose (75 mg/m2/day) temozolomide for 6 weeks. The patient was then planned to receive adjuvant chemotherapy with temozolomide (200 mg/m2) taken daily for 5 days every 4 weeks. After the 1st cycle, respiratory symptoms with progressive dyspnea and nonproductive cough developed. The patient denied fever, any chest pain, sputum production, or hemoptysis. The patient had never smoked and denied taking any herbal or over-the-counter medications. Concomitant medications used were valproated sodium (Depakin®) and acetyl-L-carnitine (Nicetile®). The patient's clinical history was negative for any other disease except glioblastoma.

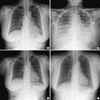

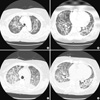

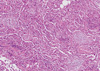

On physical examination, the patient was found to have a body temperature of 36.5℃, a blood pressure of 130/80 mmHg, a heart rate 88 beats/min, and a respiratory rate of 22 breaths/min. After receiving 2 L/min of oxygen via nasal prong, the patient had an oxygen saturation of 95%. Auscultation of the lungs revealed some inspiratory crackles in both lung bases. The heart rate was regular without evidence of cardiac murmur, and findings on the remainder of the physical examination were unremarkable. Electrocardiogram showed normal sinus rhythm and there was no ventricular dysfunction in echocardiography. Laboratory findings were within normal range with creatinine 0.9 mg/dL, albumin 3.1 g/dL, leukocyte counts being 4,200/µL and eosinophil counts being 270/µL. There was no proteinuria or hematuria in urinalysis. Chest radiograph at admission showed diffuse bilateral interstitial infiltrates (Fig. 1A). Computed tomography (CT) revealed diffuse patchy peribronchovascular ground-glass opacities and fine reticulations in both lungs (Fig. 2A, B). Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) and transbronchial lung biopsy samples were taken from the right middle and lower lobes. BAL revealed leukocyte numbers of 215/µL (neutrophils 22%, lymphocytes 45%, macrophages 33%). The biopsy specimens showed peribronchial thickening and numerous intraalveolar fibrous plugs, and thickening alveolar septa by inflammatory cells, consistent with BOOP (Fig. 3). Blood, sputum, bronchial washing, and BAL culture results for common bacteria, acid-fast bacilli, and viruses (including novel influenza H1N1) were all negative.

We started antibiotics (ceftriaxone and clarythromycin) and oseltamivir empirically from the 1st day on admission. After performing a chest CT, drug-induced BOOP was suspected, and the decision was made to discontinue temozolomide and start methylprednisolone (1 mg/kg/day). But, the patient's dyspnea became more aggravated and a follow-up chest CT (Fig. 2C, D) showed aggravated bilateral pulmonary infiltrations and both pleural effusion. On 5th day of admission, the pathological result was diagnostic of BOOP, so we increased the dose of methylprednisolone (500 mg/day for 5 days and then gradually tapered) for this rapidly progressive drug-induced BOOP case. Thereafter, the patient's symptoms and radiologic findings improved dramatically (Fig. 1C, D). The patient was discharged at the 23rd hospital day without recurrent attack.

To our knowledge, this is the first case of pathologically proven temozolomide-associated BOOP requiring high-dose corticosteroid therapy. Temozolomide is a second-generation oral alkylating agent that is mainly used in the treatment of glioblastoma multiforme, anaplastic astrocytoma, and metastatic melanoma. The drug has a favorable side effect and is generally well-tolerated. Adverse reactions are mostly hematologic, usually consisting of thrombocytopenia and neutropenia. Although mild respiratory symptoms have been described, pulmonary toxicity that requires discontinuation of therapy is very rare. Temozolomide-associated organizing pneumonitis was first reported in 2007 (3). In that case, the patient's condition was improved by a conventional dose of prednisone (1 mg/kg/day), unlike our case.

An increasing number of drugs are recognized as causing lung injury and the spectrum of their adverse effects is widening. In addition, new antineoplastic agents and regimens are constantly being added to the list of available treatments for cancer patients. Since more patients are being treated with these agents, the frequency of drug-induced pulmonary toxicity is increasing (4). However, a definitive diagnose as drug-induced pulmonary toxicity is difficult. It is important to understand the time course of the disease and suspected drug medication timing, as well as to exclude other possible diagnoses, especially infections. The responses to discontinuation of the drug and to corticosteroid treatment are also helpful. In this case, respiratory symptoms were developed after first cycle of high-dose temozolomide and we could not find the evidence of infection or other specific medication history. In addition, pathologically proven BOOP was completely resolved by high-dose corticosteroid treatment. Therefore this case meets the criteria of drug-induced BOOP.

BOOP may be classified into three categories according to its cause: BOOP of determined cause; BOOP of undetermined cause but occurring in a specific and relevant context; and cryptogenic (idiopathic) organizing pneumonia (5). The most common cause of BOOP is idiopathic, and drug-related BOOP is relatively rare. Several classes of medications cause the BOOP, including antimicrobials, anticancer agents, cardiac agents, and anti-inflammatory agents. Until now, various anticancer agents such as bleomycin, busulphan, doxorubicin, methotrexate, mitomycin-C and docetaxel have been reported in the etiology of BOOP (1, 6).

Corticosteroids are the mainstay of treatment for any cause of BOOP. More than 80% of patients with BOOP show rapid and complete resolution of the disease when medicated using steroids, although relapse can occur as the dose is reduced. The dosage is generally 1 mg/kg/day for 1-3 months, and then it should be gradually tapered for a total of 1 yr duration. A shorter 6-month course may be sufficient in certain situations (7). However, in some cases, patients present with a more aggressive clinical course with a rapidly progressive disease that is unresponsive to corticosteroids and which is associated with a high mortality (8). In corticosteroid-resistant situations, cyclophosphamide as adjunctive therapy has been used to treat BOOP (8), and other immunosuppressive agents such as azathioprine and cyclosporine A are also effective (8, 9). As another treatment method, very high dose corticosteroid therapy (methylprednisolone 125-250 mg every 6 hr IV for 3-5 days) has been suggested (10); we applied this strategy. Our patient has been receiving a tapered dose of corticosteroid for 6 months without any symptomatic or radiological recurrence.

In conclusion, rapidly progressive BOOP has a fulminant course with considerable morbidity and mortality. As described in our case, early institution of very high-dose corticosteroid therapy should be considered if drug-induced BOOP does not respond to conventional dose corticosteroid treatment.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Serial radiographic changes of the patient. Chest radiography at admission (A) shows multiple bilateral patchy nodular and interstitial opacities in both lungs. The consolidations are more aggravated at 5th hospital day (B). After high-dose corticosteroid treatment, the lesions are improved at 21st hospital day (C) and outpatient clinic examination (D).

Fig. 2

Chest computed tomography (CT) at admission (A, B) shows diffuse patchy and nodular peribronchovascular ground-glass opacities and fine reticulations with mild parenchymal distorsion in both lungs. CT acquired on the 5th hospital day (C, D) reveals increased extent and density of ground-glass opacities with aggravated parenchymal distorsion and traction bronchiectatic changes in both lungs. Moderate amount of pleural effusion is also observed.

References

1. Epler GR. Drug-induced bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia. Clin Chest Med. 2004. 25:89–94.

2. Abrey LE, Olson JD, Raizer JJ, Mack M, Rodavitch A, Boutros DY, Malkin MG. A phase II trial of temozolomide for patients with recurrent or progressive brain metastases. J Neurooncol. 2001. 53:259–265.

3. Maldonado F, Limper AH, Lim KG, Aubrey MC. Temozolomide-associated organizing pneumonitis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007. 82:771–773.

4. Vahid B, Marik PE. Pulmonary complications of novel antineoplastic agents for solid tumors. Chest. 2008. 133:528–538.

5. Cordier JF. Organising pneumonia. Thorax. 2000. 55:318–328.

6. Kim AR, Kim TY, Lee YM, Lee SH, Jung SJ, Lee HK. Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia in the patient with non-small cell lung cancer treated with docetaxel/cisplatin chemotherapy: a case report. Tuberc Respir Dis. 2010. 69:293–297.

7. Epler GR. Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia. Arch Intern Med. 2001. 161:158–164.

8. Purcell IF, Bourke SJ, Marshall SM. Cyclophosphamide in severe steroid-resistant bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia. Respir Med. 1997. 91:175–177.

9. Koinuma D, Miki M, Ebina M, Tahara M, Hagiwara K, Kondo T, Taguchi Y, Nukiwa T. Successful treatment of a case with rapidly progressive Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia (BOOP) using cyclosporin A and corticosteroid. Intern Med. 2002. 41:26–29.

10. Wells AU. Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2001. 22:449–460.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download