Abstract

Pericarditis is a rare manifestation of tuberculosis (Tb) in children. A 14-yr-old Korean boy presented with cardiac tamponade during treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis. He developed worsening anemia and persistent fever in spite of anti-tuberculosis medications. Echocardiography found free floating multiple discoid masses in the pericardial effusion. The masses and exudates were removed by pericardiostomy. The masses were composed of pink, amorphous meshwork of threads admixed with degenerated red blood cells and leukocytes with numerous acid-fast bacilli, which were confirmed as Mycobacterium species by polymerase chain reaction. The persistent fever and anemia were controlled after pericardiostomy. This is the report of a unique manifestation of Tb pericarditis as free floating masses in the effusion with impending tamponade.

Tuberculosis (Tb) is responsible for approximately 4% of cases of acute pericarditis, 7% of cases of cardiac tamponade, and, in older studies 6% of instances of constrictive pericarditis. However, in some non-industrialized countries, tuberculosis is a leading cause of pericarditis (1). Tuberculous pericarditis presents clinically 3 forms, namely, pericardial effusion, constrictive pericarditis, and a combination of effusion and constriction (2).

Echocardiography is very useful for the diagnosis of tuberculous pericardial effusion if the intrapericardial abnormalities, including exudative coating, fibrinous strands, and thickened pericardium are present (3). We experienced very unusual case of Tb pericarditis presenting as free floating multiple echogenic masses in the pericardial effusion with impending tamponade. The masses were proved to be blood clot with numerous acid-fast bacilli.

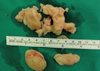

On 15 August 2010, a 14-yr old boy was transferred to our hospital for uncontrolled pneumonia. He developed cough, sputum and malaise 16 days ago, and he had been managed with antibiotics, but his symptoms were aggravated clinically and radiographically. He also showed night sweat and fever, but weight loss was absent. He had been healthy until the recent illness. He received BCG at 4 weeks of age. Tuberculosis (Tb) was absent in the family history. On physical examination, he was alert and well-nourished. His vital sign was as follows; temperature 38℃, heart rate 126/min, and respiration rate 24/min. Chest exam revealed coarse breath sound and wheezing. Tuberculin purified protein derivative skin test was negative, but sputum showed positive for acid fast bacilli (AFB). Chest radiograph on admission revealed haziness in right upper and middle lung field (Fig. 1A), and high resolution chest computerized tomography showed consolidation, micronodules and branching structures in right lung and lymph node (LN) enlargement in both hilum with pericardial effusion (Fig. 1B). He was managed as pulmonary Tb with isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide and ethambutol. The AFB was identified as M. tuberculosis and was sensitive to all the Tb medications except isoniazid in the culture study. Predinisolone was given for total 2 months with tapering. In spite of Tb medication, he complained persisting fever, aggravating cough and chest pain. Chest exam revealed decreased breath sound and chest radiograph revealed aggravated haziness in the right lung with newly appeared consolidation in right lower lung field with a pattern of pericardial effusion (Fig. 1C) on the 7th day. In the mean while, his hemoglobin decreased gradually from 11.3 g/dL to 9.6 g/dL, but C-reactive protein (CRP) initially increased from 14.5 mg/dL to 25.4 mg/dL on the 3rd hospital day, and then decreased to 7.6 mg/dL on the 9th day (Fig. 2). Echocardiography showed free floating multiple round discoid masses in large amount of pericardial effusion (Fig. 3A) and marked variation in mitral inflow Doppler with respiration suggesting impending tamponade (Fig. 3B). On the 9th day, pericardial effusion and the discoid masses were removed by pericardiostomy. Pericardial fluid was pinkish and AFB (+). The yellowish discoid masses were soft and fragile (Fig. 4). Microscopic exam revealed that the masses were composed of pink, amorphous meshwork of threads admixed with degenerated red blood cells and leukocytes (Fig. 5A) with numerous acid-fast bacilli (Fig. 5B). After pericardiostomy the fever came down and hemoglobin rose up to 11.9 g/dL and CRP came down to 0.84 mg/dL on the 30th day (Fig. 2). He is still taking anti-Tb medication with marked improvement of chest radiogram. We performed real time polymerase chain reaction (PCR, LG Life Science, Seoul, Korea) for Mycobacterium tuberculosis using paraffin-embedded tissue, and confirmed that AFB were Mycobacterium species.

It is very peculiar that Tb pericarditis manifested as multiple free-floating pericardial masses in the effusion with impending tamponade. How could the discoid masses be made in the middle of pericardial fluid? We assumed as follows. With great increase in permeability due to Tb pericarditis, hemorrhage and fibrinous exudates developed in pericardial fluid. Red blood cells and fibrinous and proteinous materials came into collision with each other, and they became conglomerated and bigger in size, and consequently discrete masses were formed in the pericardial effusion. This phenomenon might be accelerated by cardiac movement. With the compressive force in between the visceral and parietal pericardium, the masses became discoid shape.

In the literature search, we found at least two similar but different pediatric cases of Tb pericarditis in Taiwan and Africa. Lin et al. (4) reported a 10-month-old girl with fibrinofibrous pericarditis that manifested as constrictive pericarditis with prolonged fever, hepatomegaly, edema, and poor appetite. Echocardiography showed a solid mass that originated from the thickened pericardium and compressed the whole heart. The symptoms and signs dramatically improved after surgical pericardiectomy (4). Another similar African case was reported in 16-yr-old boy, who was hospitalized for fever, chest pain, and cardiovascular collapse. Echocardiography revealed a 30-mm circumferential echogenic "porridge-like" pericardial effusion with signs of cardiac tamponade. The effusion and fibrinous pockets were removed by subxiphoid pericardiotomy (5). The porridge-like pericardial effusion was echogenic and associated with fibrinous strands. The effusion in African case might be changing to solid mass similar to Taiwan and our cases.

Pericardial involvement usually develops by retrograde lymphatic spread of M. tuberculosis from peritracheal, peribronchial, or mediastinal lymph node or by hematogenous spread from primary tuberculous infection (2). Pathologically, Tb pericarditis is recognized as four stages: 1) fibrinous exudation with initial polymorphonuclear leukocytosis, relatively abundant mycobacteria, and early granuloma formation with loose organization of macrophage and T cells; 2) serosanguineous effusion with a predominantly lymphocytic exudates with monocytes and foam cells; 3) absorption of effusion with organization of granulomatous caseation and pericardial thickening caused by fibrin, collagenosis, and ultimately, fibrosis; and 4) constrictive pericardium contracts on the cardiac chambers and may become calcified, encasing the heart in a fibrocalcific skin that impedes diastolic filling and causes the classic syndrome of constrictive pericarditis (6). According to this classification, our case was clinically pericardial effusion, and pathologically in-between the stage 1 and 2. But interestingly, our case had much more bleeding, because the masses were actually blood clots and the patient showed decreasing hemoglobin level.

Definitive diagnosis of Tb pericarditis was based on 1 of following criteria: 1) positive Mycobacterium tuberculosis culture from pericardial effusion or tissue, 2) positive AFB or caseous granuloma on pericardial biopsy specimen, or 3) positive PCR in pericardial biopsy specimen (3). The variability in the detection of tubercle bacilli in the direct smear examination of pericardial fluid ranges from 0% to 42%. Positivity of cultures of the pericardial fluid ranges from 50% to 75% (2). Our case was positive for AFB in both sputum and pericardial fluid, as well as positive PCR result in the tissue. Also in the culture study, the AFB was identified as M. tuberculosis. Echocardiographic findings of effusion with fibrous strands on the visceral pericardium are typical but not specific for tuberculous pathogenesis (1). Three echocardiographic features were emphasized in the diagnosis of Tb pericarditis as follows; 1) exudative coating defined as the presence of shaggy echo-dense images with mass-like appearance surrounding the epicardium, 2) fibrinous strands defined as multiple linear or band-like structures from the epicardium or pericardium protruding into the pericardial space, 3) thickened pericardium more than 2 mm on 2-dimensional echocardiogram (3, 7). We also found thickened pericardium and shaggy echo-dense appearance surrounding the epicardium.

The optimal management includes an open pericardial window with biopsy, both for diagnosis and to prevent re-accumulation of fluid (8). Since pericardiocentesis may fail in cases of advanced-stage fibrinous effusion, pericardiotomy with complete open draining is the only lifesaving procedure (5). Anti-tuberculous chemotherapy increases survival dramatically in Tb pericarditis. A regimen consisting of rifampicin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol for at least 2 months, followed by isoniazid and rifampicin (total of 6months of therapy) has been shown to be highly effective in treating patients with extrapulmonary Tb (2, 9). Controversy exists with respect to the use of corticosteroids for Tb pericarditis. Corticosteroids probably offer some benefit in preventing fluid re-accumulation as well. The American Thoracic Society's consensus statement recommends adjunctive therapy with corticosteroids (1 mg/kg of prednisolone with tapering over 11 weeks) for tuberculous pericarditis on the basis of two randomized, double-blind, controlled trials in South Africa, although those studies had statistically no significant impact (9). In the first study, patients in the later effusive-constrictive phase who received prednisolone had a significantly more rapid clinical resolution compared with patients given placebo. But, prednisolone did not reduce the risk of constrictive pericarditis (10). In the second trial involving patients with effusive pericarditis, prednisolone reduced the need for repeated pericardiocentesis and was associated with significantly lower mortality (11). According to the above American Thoracic Society's consensus statement recommendation, we used 4 drug regimen initially and prednisolone for 2 months with tapering.

This is the unique report of a patient who rapidly developed Tb pericarditis with free floating discoid masses in the effusion and impending tamponade during treatment of pulmonary Tb.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Radiologic findings of the chest. (A) Haziness in right upper and middle lung was noted. (B) Consolidation, micronodules, and branching structures were found in the right lung, and lymph node enlargements were noted in both hilum. (C) Aggravated haziness in the right lung and newly appeared consolidation in the right lower lung were found on 7th hospital day.

Fig. 2

Hemoglobin (Hb) was decreased gradually since admission till the 9th hospital day (HD), when pericardiostomy was performed. C-reactive protein (CRP) increased initially and then decreased. After pericardiostomy, hemoglobin increased till discharge and CRP also decreased to normal at discharge.

Fig. 3

Echocardiographic findings. (A) Free floating multiple round discoid echogenic masses in the large amount of pericardial effusion, the thickened pericardium and shaggy echo-dense appearance surrounding the epicardium in subcostal view, and (B) marked variation in mitral inflow Doppler pattern.

References

1. Fowler NO. Tuberculous pericarditis. JAMA. 1991. 266:99–103.

2. Mayosi BM, Burgess LJ, Doubell AF. Tuberculous pericarditis. Circulation. 2005. 112:3608–3616.

3. Liu PY, Li YH, Tsai WC, Tsai LM, Chao TH, Yung YJ, Chen JH. Usefulness of echocardiographic intrapericardial abnormalities in the diagnosis of tuberculous pericardial effusion. Am J Cardiol. 2001. 87:1133–1135.

4. Lin JH, Chen SJ, Wu MH, Lee PI, Chang CI. Fibrinofibrous pericarditis mimicking a pericardial tumor. J Formos Med Assoc. 2000. 99:59–61.

5. Massoure PL, Boddaert G, Caumes JL, Gaillard PE, Lions C, Grassin F. Porridge-like tuberculous cardiac tamponade: treatment difficulties in the Horn of Africa. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010. 58:276–278.

6. Tirilomis T, Unverdorben S, von der Emde J. Pericardectomy for chronic constrictive pericarditis: risks and outcome. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1994. 8:487–492.

7. Bolt RJ, Rammeloo LA, van Furth AM, van Well GT. A 15-year-old girl with a large pericardial effusion. Eur J Pediatr. 2008. 167:811–812.

8. Trautner BW, Darouiche RO. Tuberculous pericarditis: optimal diagnosis and management. Clin Infect Dis. 2001. 33:954–961.

9. Blumberg HM, Burman WJ, Chaisson RE, Daley CL, Etkind SC, Friedman LN, Fujiwara P, Grzemska M, Hopewell PC, Iseman MD, Jasmer RM, Koppaka V, Menzies RI, O'Brien RJ, Reves RR, Reichman LB, Simone PM, Starke JR, Vernon AA. American Thoracic Society/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Infectious Diseases Society. American Thoracic Society/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/Infectious Diseases Society of America: treatment of tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003. 167:603–662.

10. Strang JI, Gibson DG, Nunn AJ, Kakaza HH, Girling DJ, Fox W. Controlled trial of prednisolone as adjuvant in treatment of tuberculous constrictive pericarditis in Transkei. Lancet. 1987. 2:1418–1422.

11. Strang JI, Gibson DG, Mitchison DA, Girling DJ, Kakaza HH, Allen BW, Evans DJ, Nunn AJ, Fox W. Controlled clinical trial of complete open surgical drainage and of prednisolone in treatment of tuberculous pericardial effusion in Transkei. Lancet. 1988. 2:759–764.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download