Abstract

A 52-yr-old male with alcoholic liver cirrhosis was hospitalized for hematochezia. He had undergone small-bowel resection due to trauma 15 yr previously. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy showed grade 1 esophageal varices without bleeding. No bleeding lesion was seen on colonoscopy, but capsule endoscopy showed suspicious bleeding from angiodysplasia in the small bowel. After 2 weeks of conservative treatment, the hematochezia stopped. However, 1 week later, the patient was re-admitted with hematochezia and a hemoglobin level of 5.5 g/dL. Capsule endoscopy was performed again and showed active bleeding in the mid-jejunum. Abdominal computed tomography revealed a varix in the jejunal branch of the superior mesenteric vein. A direct portogram performed via the transhepatic route showed portosystemic collaterals at the distal jejunum. The patient underwent coil embolization of the superior mesenteric vein just above the portosystemic collaterals and was subsequently discharged without re-bleeding. At 8 months after discharge, his condition has remained stable, without further bleeding episodes.

Jejunal varices are an uncommon manifestation of portal hypertension and are rarely symptomatic (1). Acute bleeding has been reported in 5.5% of patients with portal hypertension and small bowel varices (2). Jejunal varices are associated with portal hypertension, which may be due to cirrhosis or extrahepatic portal venous obstruction, chronic alcoholism, portal vein thrombosis, or intrahepatic arterioportal fistulas (3). Ectopic varices tend to develop at sites of tissue adhesion in patients who have previously undergone abdominal surgery (4) and may occur in combination with jejunal variceal bleeding. Esophagogastric varices, in contrast, are caused primarily by portal hypertension.

Traditionally, jejunal variceal bleeding has been treated surgically (5, 6). Non-surgical treatment options include porto-caval shunt (7, 8), endoscopic sclerotherapy (9), embolization (8, 10-12), and balloon dilatation and stent placement in the portal vein for extrahepatic portal venous obstruction (4, 13).

Here, we report a case of ectopic jejunal variceal bleeding that was treated successfully by percutaneous coil embolization via the superior mesenteric vein.

A 52-yr-old male was admitted for hematochezia on 5 February 2009. Fifteen years previously, he had undergone a laparotomy for the repair of a small bowel perforation due to blunt trauma. Seven years ago, he was diagnosed with alcoholic liver cirrhosis. Balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous occlusion (BRTO) was performed for gastric variceal bleeding 3 months prior to admission. Upon admission to our hospital, he underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD), which showed a grade 1 esophageal varix without bleeding. Colonoscopy revealed no lesion that explained the hematochezia. Capsule endoscopy showed angiodysplasia in the small bowel, suspected of causing the hematochezia. The patient was treated conservatively for 2 weeks. His melena ceased and he was discharged 5 weeks after admission. However, 1 week after discharge, he was re-admitted for hematochezia, which reportedly occurred 3-4 times a day. He had not consumed any alcohol after the discharge. His blood pressure was 106/37 mmHg and his heart rate was 91 beats/min. He had a hemoglobin count of 5.5 g/dL, a platelet count of 149,000/µL, a prothrombin time of 15.8 s (international normalized ratio: 1.36), and an albumin concentration of 3.0 g/dL. There was no encephalopathy but he had mild ascites and a Child-Pugh score of 7. Serologic viral markers showed HBsAg/Ab (-/+), anti-HCV Ab (-).

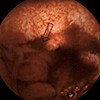

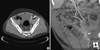

Emergency EGD showed non-bleeding, grade 1 esophageal varices. Hematochezia at the sigmoid colon and rectum was noted on colonoscopy, but there was no active bleeding lesion. Intestinal segments above the sigmoid colon could not be examined because of poor visualization due to the presence of a blood clot. Capsule endoscopy showed active bleeding at the mid-jejunum and bloody staining of the bowel wall below the mid-jejunal level (Fig. 1). Abdominal enhanced computed tomography (CT) showed liver cirrhosis, splenomegaly with mild ascites, varices of the jejunal branch of the superior mesenteric vein, and edematous change at the ascending colon and gall bladder (Fig. 2). Based on these findings, jejunal variceal bleeding was suspected.

A direct portogram performed via the transhepatic route showed hepatofugal flow into the superior mesenteric vein and multiple dilated portosystemic shunts from the superior mesenteric vein to both internal iliac veins (Fig. 3A-D). There was no evidence of active bleeding. Coil embolization was performed at the superior mesenteric vein just above the portosystemic collaterals to decompress the variceal pressure (Fig. 3E).

The patient was discharged without re-bleeding after the procedure. Eight months after discharge he remains in stable condition, with no further bleeding.

Jejunal variceal bleeding, although rare, can be life threatening without treatment. The three clinical features of small-bowel varices are portal hypertension, a history of abdominal surgery, and hematochezia without hematemesis (5, 14). The case described here shows that jejunal variceal bleeding can be treated successfully with percutaneous coil embolization via the superior mesenteric vein.

Portal hypertension due to baseline alcoholic liver cirrhosis, a history of abdominal surgery, and recent BRTO likely explained our patient's jejunal varices. Baseline alcoholic liver cirrhosis is known to induce portal hypertension and, frequently, esophageal and jejunal varices. Moreover, the severity of hepatic failure is a risk factor for gastroesophageal varix (15, 16). In contrast, in patients with portal hypertension, there is less association between other factors, such as age, gender, presence of cirrhosis, gastroesophageal varices, and Child-Pugh class C, and varices occurring in the small bowel (2).

A history of abdominal surgery is also a known predisposing factor for jejunal variceal bleeding (5). Previous abdominal surgery can lead to the development of ectopic varices at the abdominal surgical site or they may be a consequence of postsurgical stricture in the small bowel (4). Small-bowel varices due to prior abdominal surgery may result from the mesenteric hypertension caused by mesenteric vein stenosis or from portal hypertension. Thus, in a patient with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding, a history of abdominal surgery, and portal hypertension, small-bowel varices at the anastomotic site or the postoperative stricture site should be considered.

BRTO procedures for the treatment of gastric varices may induce a significant elevation in the portal systemic pressure gradient (17). In our patient, recent BRTO might have aggravated the portal systemic pressure gradient, thereby inducing jejunal variceal bleeding.

While the patient may have had jejunal varices at first admission, there was no evidence for their presence on a capsule endoscopy image and it was assumed that the cause of hematochezia was angiodysplasia of the small bowel. Jejunal variceal bleeding is difficult to diagnose and is best confirmed using abdominal enhanced CT, capsule endoscopy, abdominal angiography, or 99mTc-labeled red blood cell scanning (14). In some cases, push enteroscopy and ileoscopy may be useful diagnostically (18). Capsule endoscopy is highly sensitive for the detection of fresh blood in the small bowel. However, it is of limited usefulness for the diagnosis of small-bowel varices because the mucosal layer covering the varices can exhibit a mosaic pattern, a shining pattern, or normal features. Blood clots can cover the varices. Therefore, clinical suspicion is key to diagnosis (19).

The treatment of jejunal varices includes surgery (5, 6), transjugular intrahepatic porto-systemic shunt (TIPS) (7, 8), enteroscopic sclerotherapy (9), percutaneous embolization (8, 10-12), and dilatation of a stenosed portal vein followed by stent placement (4, 13). Treatment for segmental varices in which there is superior mesenteric vein stricture without portal hypertension involves surgical resection. In the presence of systemic portal hypertension, a TIPS or a decompressive shunting procedure is recommended (18).

For small-bowel varices with extrahepatic portal vein obstruction, surgery and TIPS are not only invasive but are relatively difficult to perform. Additionally, inflammation, trauma, and/or severe abdominal adhesion are common postoperatively (10). Superior mesenteric vein embolization and portal vein angioplasty with stent insertion are options in patients in whom surgery is not possible due to portal hypertension and extrahepatic obstruction (10, 13). These procedures can also be performed successfully in patients with jejunal variceal bleeding related to extrahepatic portal vein obstruction but without portal hypertension (20). The Child-Pugh score of our patient at admission was 7, and he had no evidence of hepatic failure. Possible causes of jejunal variceal bleeding were portal hypertension due to stricture at the anastomotic site, intra-abdominal adhesion, and extrahepatic portal venous obstruction from previous small-bowel surgery, rather than aggravation of alcoholic liver cirrhosis. He had no portal vein obstruction. Intervention angiography was selected as a first-line therapy rather than TIPs, due to the presence of mild ascites and grade 1 esophageal varices, and the risk of hepatic encephalopathy. Coil embolization as a first-line treatment resulted in a successful outcome for our cirrhotic patient.

In summary, we report the case of a patient with jejunal variceal bleeding who was treated successfully by percutaneous coil embolization. Further studies are needed to confirm the use of embolization as an interventional first-line therapy for small-bowel variceal bleeding.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Capsule endoscopic findings show blood-stained mucosa below the mid-jejunum, with suspected active bleeding (arrow) of a jejunal varix.

Fig. 2

Jejunal varices and main portal vein in multidetector CT; Axial scan and multiplanar reformation in multidetector CT show multiple and dilated jejunal varices (arrow). Note the main portal vein (small arrows) in the multiplanar reformation.

Fig. 3

Serial direct portogram and coil embolization; Serial direct portogram shows hepatofugal flow into the superior mesenteric vein and multiple dilated portosystemic shunts from the superior mesenteric vein to both internal iliac veins (A-D). Coil embolization of the superior mesenteric vein was performed just above the portosystemic shunts (E).

References

1. Hamlyn AN, Morris JS, Lunzer MR, Puritz H, Dick R. Portal hypertension with varices in unusual sites. Lancet. 1974. 2:1531–1534.

2. Figueiredo P, Almeida N, Lérias C, Lopes S, Gouveia H, Leitão MC, Freitas D. Effect of portal hypertension in the small bowel: an endoscopic approach. Dig Dis Sci. 2008. 53:2144–2150.

3. Filik L, Odemiş B, Köklü S, Tola M, Yurdakul M, Sahin B. Arterioportal fistula causing jejunal variceal hemorrhage. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2003. 14:266–269.

4. Hiraoka K, Kondo S, Ambo Y, Hirano S, Omi M, Okushiba S, Katoh H. Portal venous dilatation and stenting for bleeding jejunal varices: report of two cases. Surg Today. 2001. 31:1008–1011.

5. Yuki N, Kubo M, Noro Y, Kasahara A, Hayashi N, Fusamoto H, Ito T, Kamada T. Jejunal varices as a cause of massive gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992. 87:514–517.

6. Bhagwat SS, Borwankar SS, Ramadwar RH, Naik AS, Gajaree GI. Isolated jejunal varices. J Postgrad Med. 1995. 41:43–44.

7. Vangeli M, Patch D, Terreni N, Tibballs J, Watkinson A, Davies N, Burroughs AK. Bleeding ectopic varices: treatment with transjugular intrahepatic porto-systemic shunt (TIPS) and embolisation. J Hepatol. 2004. 41:560–566.

8. Robert B, Yzet T, Bartoli E, M'Bayo D, Dupas JL, Nguyen-Khac E. Embolization of recurrent bleeding jejunal varices. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2010. 34:100–103.

9. Getzlaff S, Benz CA, Schilling D, Riemann JF. Enteroscopic cyanoacrylate sclerotherapy of jejunal and gallbladder varices in a patient with portal hypertension. Endoscopy. 2001. 33:462–464.

10. Sato T, Yasui O, Kurokawa T, Hashimoto M, Asanuma Y, Koyama K. Jejunal varix with extrahepatic portal obstruction treated by embolization using interventional radiology: report of a case. Surg Today. 2003. 33:131–134.

11. Lim LG, Lee YM, Tan L, Chang S, Lim SG. Percutaneous paraumbilical embolization as an unconventional and successful treatment for bleeding jejunal varices. World J Gastroenterol. 2009. 15:3823–3826.

12. Sasamoto A, Kamiya J, Nimura Y, Nagino M. Successful embolization therapy for bleeding from jejunal varices after choledochojejunostomy: report of a case. Surg Today. 2010. 40:788–791.

13. Sakai M, Nakao A, Kaneko T, Takeda S, Inoue S, Yagi Y, Okochi O, Ota T, Ito S. Transhepatic portal venous angioplasty with stenting for bleeding jejunal varices. Hepatogastroenterology. 2005. 52:749–752.

14. Joo YE, Kim HS, Choi SK, Rew JS, Kim HR, Kim SJ. Massive gastrointestinal bleeding from jejunal varices. J Gastroenterol. 2000. 35:775–778.

15. Burroughs AK. The natural history of varices. J Hepatol. 1993. 17:S10–S13.

16. Benedeto-Stojanov D, Nagorni A, Mladenović B, Stojanov D, Denić N. Risk and causes of gastroesophageal bleeding in patients with liver cirrhosis. Vojnosanit Pregl. 2007. 64:585–589.

17. Tanihata H, Minamiguchi H, Sato M, Kawai N, Sonomura T, Takasaka I, Nakai M, Sahara S, Nakata K, Shirai S. Changes in portal systemic pressure gradient after balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration of gastric varices and aggravation of esophageal varices. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2009. 32:1209–1216.

18. Tang SJ, Jutabha R, Jensen DM. Push enteroscopy for recurrent gastrointestinal hemorrhage due to jejunal anastomotic varices: a case report and review of the literature. Endoscopy. 2002. 34:735–737.

19. Tang SJ, Zanati S, Dubcenco E, Cirocco M, Christodoulou D, Kandel G, Haber GB, Kortan P, Marcon NE. Diagnosis of small-bowel varices by capsule endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004. 60:129–135.

20. Deshpande A, Sampat P, Bhargavan R, Sharma M. Bleeding isolated jejunal varices without portal hypertension. ANZ J Surg. 2008. 78:814–815.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download