Abstract

The bacilli Calmette-Guérin (BCG) Tokyo-172 strain was considered to exhibit good protective efficacy with a low rate of unfavorable side effects. However, we describe a rare case of BCG osteomyelitis developed in an immunocompetent host who was given with BCG Tokyo-172 vaccine on the left upper arm by multipuncture method. A 9-month-old girl presented with progressive inability to move her right elbow and had radiographic evidence of septic elbow combined with osteomyelitis of right distal humerus. A biopsy from the site revealed chronic caseating granulomatous inflammation, positive for BCG Tokyo-172 strain on the multiplex polymerase chain reaction. The child had to undergo second surgical debridements and oral antituberculosis chemotherapy. There were no sequelae after 2 yr of follow-up. This complication, although uncommon, should be considered in the appropriate clinical setting.

Tokyo-172 BCG vaccine has been admitted by the quality control of World Health Organization (WHO) and reported to have a lower residual virulence and less reactogenicity. The vaccine was considered to exhibit favorable characteristics with regard to both efficacy and side reactions (1). Nevertheless, there were some severe adverse reactions that developed beyond vaccination site and regional ipsilateral axillary lymph-nodes. The risk of severe adverse reactions was high among those of primary immunodeficiency. Osteomyelitis is a very rare but serious late complication of BCG-immunization in immunocompetent individuals and results from generalized dissemination of BCG (2).

Here, we report a rare case of BCG osteomyelitis of the elbow in a 9-month-old girl who had no underlying immunodeficiency disorders.

A 9-month-old Korean girl was referred to our clinic because of a progressive inability to move her right elbow on January 9, 2007. Approximately 3 weeks ago, the child was seen by a local orthopedic physician. The parents had noted that she was reluctant to move her right arm through complete ranges. Also, the patient would cry when the arm was abducted. At that time, the doctor of the local clinic had an initial diagnosis of a pulled elbow, in which the arm was reducted and put into an arm cast. Three days later, painful swelling in her right elbow developed with the limitation in active movement and inability to rotate.

The patient was born by normal vaginal delivery with normal Apgar score. She was vaccinated with Tokyo-172 BCG on the left upper arm at one month of age. BCG vaccine was administered percutaneously by multipuncture method. She had received routine immunizations up to date including hepatitis B, diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis (DTaP), polio (IPV) in accordance with the national vaccination program guidelines. She lived in Ansan and had no history of farm or zoo visit. The patient had no previous history of illness and no known familial tuberculosis history. Physical examination revealed obvious swelling, erythema, tenderness in the area of the right elbow. Furthermore, the range of elbow movement was restricted. Other physical examinations were normal.

The laboratory results at admission revealed the erythrocyte sedimentation rate 107 mm/hr and C-reactive protein (CRP) 1+. Radiological studies suggested the lesion in the elbow. Also, MRI revealed contrast enhancement in and around the right elbow, compatible with septic elbow. Signal change and contrast enhancement in the epiphysis and metaphysis of right distal humerus were noted. These features suggested septic elbow combined with osteomyelitis. No other significant abnormal finding was shown in other skeletal areas.

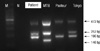

Initially, septic elbow was diagnosed and surgery was performed to treat osteomyelitis of right elbow and revealed concentrated dirty granulation tissue in the elbow joint space that was removed. After operation, the child had been treated with ampicillin/sulbactam before the proper diagnosis had been established. Since the osteomyelitis lesion was refractory with antibiotic therapy, we considered mycobacterium as the pathogen. A lesion biopsy specimen was sent to the pathology department. Histopathological examination of the biopsy specimen revealed a chronic caseating granulomatous inflammatory reaction. Microscopic examination of the pus with Ziehl-Neelsen staining showed no Acid-fast bacilli but a culture of the biopsy was identified with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. As the postoperative diagnosis was osteomyelitis of M. tuberculosis, we started treatment with regimen of rifampin, isoniazid and pyrazinamide. Following the culture report, the sensitivity test showed that the strain was resistant to pyrazinamide. This sensitivity study was a distinguishing characteristic of M. bovis. Therefore, we requested multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for the Mycobacterium complex colony to differentiate the pathogen. A mycobacterium culture of the biopsy sample later revealed to have an identical amplification with the BCG Tokyo-172 strain on the multiplex PCR for the Mycobacterium complex colony (Fig. 1). Based on these findings, the diagnosis of osteomyelitis due to Tokyo-172 BCG vaccination was confirmed.

Immunological investigation for the evaluation of cellular and humoral immunity was performed, including complement CH50, C3, and C4, immunoglobulins and intracellular oxidation (dihydrorhodamine) and revealed normal findings. Therefore, immunodeficiency disorders were ruled out. In addition, an evaluation for extrapulmonary TB was negative.

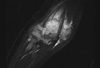

The patient had been treated with a regimen consisting of rifampin (10 mg/kg body weight per day), isoniazid (10 mg/kg body weight per day) and pyrazinamide (25 mg/kg body weight per day) as an outpatient. However, after two months of treatment, MRI showed no interval change (Fig. 2). We added streptomycin (30 mg/kg body weight per day intramuscularly for 10 days) and ethambutol (15 mg/kg body weight per day) instead of pyrazinamide due to the sensitivity result. Pyrazinamide was eliminated because of it is generally considered ineffective for the treatment of BCG osteomyelitis. Following the change of regimen, debridement and curettage was again performed four months after the first surgery. The planned chemotherapy regimen was continued during 12 months. She has been followed up for 2 yr and has remained without signs of growth disturbances or impairment of function in adjacent joints. The function of the right arm was normal in terms of range of motion and activity. The most recent radiological examination showed the decrease of geographic osteolytic lesion on the distal humerus and periosteal reaction, disappearance of neighboring soft tissue swelling, which suggested improving state of osteomyelitis and arthritis. The patient recovered without complications.

The prevalence of tuberculosis in Korea was higher than in other OECD countries. Subsequently, BCG vaccination emerged as a national policy for the control of tuberculosis. In Korea, 95%-99% of children are vaccinated with BCG within the first month of life. Two types of BCG vaccine are currently used in Korea. The usage of all freeze-dried BCG vaccine (Danish 1331, Denmark, Statens Serum Institue) was approved officially on the National Immunization Program guidelines. The Tokyo-172 BCG also has been used for the last 15 yr.

In recent years, unfortunately, unfavorable adverse reactions of BCG vaccination were occasionally documented. The most serious side effect is generalized BCG infection. Bone and joint tuberculosis after BCG vaccination has been described mostly by Scandinavian authors (3-5). Hematogenous spread of BCG may result in osteomyelitis, but this is a rare complication. The incidence rate of BCG osteomyelitis was reported to be 1.11 cases in a million in Europe (5, 6). Since then, only rare cases of BCG osteomyelitis have been reported in Asia (7-9). The incidence and type of complication with BCG vaccination depend on the strain and administration modalities, but no single cause has been defined (10).

It has been shown that the BCG Tokyo-172 strain exhibits good protective efficacy with a low rate of unfavorable side effects (1, 11, 12). The WHO Expert Committee on Biological Standardization determined the formulation of international requirements for manufacture and control of BCG vaccine (1). The Tokyo-172 BCG vaccine met the requirements and had a good safety record. So some pediatric practitioners in Korea use BCG Tokyo-172 vaccine with paying the expensive price particularly because of expecting a low rate of complications. However, a systemic review of adverse reactions has not been established in Korea as in Japan and in Taiwan (13, 14).

As we describe a rare case of osteomyelitis as a complication of BCG Tokyo-172 vaccine, it shows that the severe side effect can be associated with the Tokyo-172 strain. According to the previous reported cases, the lesion tended to appear on the same side of the body as the vaccination. In our patient, the hematogenous spread is the likely cause as the lesion is located on the opposite side of the injection site (in the left deltoid region). And the lesion did not improve sufficiently with an initial treatment by surgical debridement and oral antituberculosis chemotherapy, including the use of isoniazid and rifampicin, although the Tokyo-172 strain isolated from the lesion was susceptible to isoniazid and rifampicin. This indicated that our patient had refractory BCG osteomyelitis.

In terms of efficacy, no consensus exists as to which strains of BCG is the best for general use. The benefit with Tokyo-172 BCG vaccine has been shown; however, few studies have demonstrated the occurrence of severe adverse effect with this strain in Korea. To date, only 2 other cases of BCG Tokyo-172 related osteomylitis have been reported in Korea (15). New assessment and comparison are required to address the challenges raised by the Tokyo 172 strain in particular. The follow-up of BCG complications is an essential task of BCG vaccination program.

We learned that clinicians should consider BCG osteomyelitis when the BCG vaccinated child presenting tuberculous osteomyelitis. Most BCG osteomyelitis shows favorable prognosis with oral antituberculsosis chemotherapy or surgical debridement and oral antituberculsosis chemotherapy. However, our case had to undergo second operation despite the oral antituberculosis chemotherapy due to initial mistaken-diagnosis. It is difficult to distinguish BCG osteomyelitis, because it is very rare disease with a long latent period between the vaccination and the onset of symptoms. The clinical presentation of BCG osteomyelitis is non-specific and radiographic findings are also not extraordinary. Without considering this condition, the diagnosis and treatment can be delayed as in the case of our patient. Moreover, culture is time-consuming, resulting in a delay in the initiation of the specific treatment. Recently, multiplex PCR method have been utilized and proved to be a rapid and reliable method (16-18). The detection of BCG substrains using the multiplex PCR allowed us to differentiate BCG Tokyo-172 osteomyelitis from other mycobacterial infections.

As this case report demonstrates, BCG Tokyo-172 vaccine may be complicated by hematogenous spread to the bone. A high-index of suspicion of BCG-related osteomylitis is crucial, and confirmation of the pathogen can be helpful with using of PCR.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

The detection of BCG substrain using the multiplex polymerase chain reaction. The sample of this patient shows an identical amplification with the Mycobacterium bovis BCG Tokyo-172 strain. M, marker; N, negative; MTB, M. tuberculosis; Pasteur, M. bovis BCG Pasteur; Tokyo, M. bovis BCG Tokyo-172.

References

1. Yamamoto S, Yamamoto T. Historical review of BCG vaccine in Japan. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2007. 60:331–336.

2. Khotaei GT, Sedighipour L, Fattahi F, Pourpak Z. Osteomyelitis as a late complication of Bacille Calmette-Guérin vaccination. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2006. 39:169–172.

3. Bergdahl S, Felländer M, Robertson B. BCG osteomyelitis: experience in the Stockholm region over the years 1961-1974. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1976. 58:212–216.

4. Berges O, Boccon-Gibod L, Berger JP, Fauré C. Case report 165: BCG-osteomyelitis of the proximal end of the humerus with an abscess dissecting into the deltoid muscle. Skeletal Radiol. 1981. 7:75–77.

5. Böttiger M, Romanus V, de Verdier C, Boman G. Osteitis and other complications caused by generalized BCG-itis. Experiences in Sweden. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1982. 71:471–478.

6. Lotte A, Wasz-Höckert O, Poisson N, Dumitrescu N, Verron M, Couvet E. BCG complications. Estimates of the risks among vaccinated subjects and statistical analysis of their main characteristics. Adv Tuberc Res. 1984. 21:107–193.

7. Chan PK, Ng BK, Wong CY. Bacille Calmette-Guérin osteomyelitis of the proximal femur. Hong Kong Med J. 2010. 16:223–226.

8. Funato M, Kaneko H, Matsui E, Teramoto T, Kato Z, Fukao T, Okusu K, Kondo N. Refractory osteomyelitis caused by bacille Calmette-Guerin vaccination: a case report. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2007. 59:89–91.

9. Han JS, Chung DW, Song YS, Kim JM. Tuberculous osteomyelitis on the proximal humerus after BCG vaccination: a case report. J Korean Orthop Assoc. 1997. 32:1137–1141.

10. Abu-Nader R, Terrell CL. Mycobacterium bovis vertebral osteomyelitis as a complication of intravesical BCG use. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002. 77:393–397.

11. Hayashi D, Takii T, Fujiwara N, Fujita Y, Yano I, Yamamoto S, Kondo M, Yasuda E, Inagaki E, Kanai K, Fujiwara A, Kawarazaki A, Chiba T, Onozaki K. Comparable studies of immunostimulating activities in vitro among Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) substrains. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2009. 56:116–128.

12. Ritz N, Hanekom WA, Robins-Browne R, Britton WJ, Curtis N. Influence of BCG vaccine strain on the immune response and protection against tuberculosis. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2008. 32:821–841.

13. Toida I, Nakata S. Severe adverse reactions after vaccination with Japanese BCG vaccine: a review. Kekkaku. 2007. 82:809–824.

14. Jou R, Huang WL, Su WJ. Tokyo-172 BCG vaccination complications. Taiwan. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009. 15:1525–1526.

15. Kim SH, Kim SY, Eun BW, Yoo WJ, Park KU, Choi EH, Kim EC, Lee HJ. BCG osteomyelitis caused by the BCG Tokyo strain and confirmed by molecular method. Vaccine. 2008. 26:4379–4381.

16. Talbot EA, Williams DL, Frothingham R. PCR identification of Mycobacterium bovis BCG. J Clin Microbiol. 1997. 35:566–569.

17. Yan JJ, Chen FF, Jin YT, Chang KC, Wu JJ, Wang YW, Su IJ. Differentiation of BCG-induced lymphadenitis from tuberculosis in lymph node biopsy specimens by molecular analyses of pncA and oxyR. J Pathol. 1998. 184:96–102.

18. Frothingham R. Differentiation of strains in Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex by DNA sequence polymorphisms, including rapid identification of M. bovis BCG. J Clin Microbiol. 1995. 33:840–844.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download