Abstract

Acute kidney injury (AKI) secondary to near-drowning is rarely described and poorly understood. Only few cases of severe isolated AKI resulting from near-drowning exist in the literature. We report a case of near-drowning who developed to isolated AKI due to acute tubular necrosis (ATN) requiring dialysis. A 21-yr-old man who recovered from near-drowning in freshwater 3 days earlier was admitted to our hospital with anuria and elevated level of serum creatinine. He needed five sessions of hemodialysis and then renal function recovered spontaneously. Renal biopsy confirmed ATN. We review the existing literature on near-drowning-induced AKI and discuss the possible pathogenesis.

Acute kidney injury (AKI) secondary to immersion and near-drowning is rarely described and poorly understood. Much of the literature of near-drowning has concentrated on the respiratory effects of aspiration of salt and freshwater, and on the management of both early and late respiratory complications such as aspiration pneumonia and adult respiratory distress syndrome (1). However, near-drowning and immersion can have profound effects on other end organs such as cerebral (hypoxic brain injury, cerebral edema) (2), cardiac (atrial fibrillation) (3) and hematologic complications (coagulopathy and hemolysis) (4). Moreover, multisystem failure resulting from near-drowning is also well described (5). Near-drowning induced acute kidney injury (AKI) is not uncommon and is heterogenous clinical entity (6). Although the resultant AKI is usually mild and self-limited, severe cases such as AKI associated with shock, multisystem failure, rhabdomyolysis (7, 8) and isolated AKI can occur (6). Only few cases of severe isolated AKI due to acute tubular necrosis (ATN) resulting from near-drowning exist in the literature. We report a case of near-drowning who developed severe isolated AKI requiring dialysis due to biopsy-confirmed ATN.

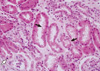

A 21-yr-old man was admitted to this hospital because of anuria and nausea on June 11, 2011. He had been well until 3 days before admission, when he went to swim in the lake with his friends. He was exhausted before got back to the shore, and was suffocating. He was unconscious briefly (about 2-3 min) until rescued by his friend. He was transported to the emergency room of another hospital. On physical examination, he was conscious but sleepy; blood pressure was 132/68 mmHg, body temperature was 36.9℃, and pulse was 114 beats per minute; respiration was 20 per minute, and the oxygen saturation was 96% while the patient was breathing ambient air. Laboratory tests revealed serum creatinine level of 1.4 (0.4-1.3) mg/dL, total carbon dioxide (TCO2) of 9.8 (24-30) mM/L, anion gap of 27.2 mM/L, hemoglobin concentration of 16.7 g/dL, and leukocyte count of 12,300/µL (lymphocyte 41.1%). Electrocardiogram and chest radiography were normal. The patient was discharged after 12 hr observation period. He was admitted to our hospital 3 days later, complaining of being tired, anorexic and anuric. The vital signs were as follows: blood pressure, 140/90 mmHg; pulse, 75 beats per minute; respiration, 20 per minute; and body temperature, 37.6℃. Laboratory findings showed blood urea nitrogen (BUN) of 42.7 (6-26) mg/dL, serum creatinine of 11.5 mg/dL, seum cystatin C level of 3.39 (0.5-1.10) mg/L, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) of 6 (10-40) IU/L, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) of 9 (6-40) IU/L, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) of 435 (218-472) IU/L, creatine kinase (CK) of 225 (5-217) U/L, myoglobin of 87.9 (15.2-91.2) ng/mL, TCO2 of 15.4 (20-28) mM/L, anion gap of 19.3 mM/L, hemoglobin concentration of 13.1 g/dL, and leukocyte count of 11,180/µL (segmented neutrophil 86.5%, lymphocyte 8.1%). There was no elevation of infectious or immunological marker. Urinalysis showed a trace of blood and 1+ proteinuria. A spot urine protein creatinine ratio was 634.37 mg/g. The hourly urine output was less than 10 mL despite of bolus infusion of normal saline and continuous infusion of furosemide. A chest roentgenogram initially showed mild pulmonary congestion with bilateral pleural effusion. Non-contrast enhanced abdominal computed tomography showed normal sized kidneys without urinary tract obstruction. A bone imaging study using Tc-99m-methylene diphosphonate showed no soft tissue uptake. The patient needed five sessions of dialysis over the succeeding 5 days and serum creatinine level was 5.12 mg/dL on the next day after the last hemodialysis session, then we stopped hemodialysis treatment. On the 9th hospital day, serum creatinine level was 3.05 mg/dL, we planned renal biopsy that had been postponed because of bleeding risk. The next day, serum creatinine level was 1.98 mg/dL and renal biopsy was performed. The renal tubular epithelial cells were denuded and had exfoliating brush borders and intermittent mitosis due to regeneration. The interstitium was edematous and had mild infiltration of lymphocytes, but the glomeruli showed unremarkable finding (Fig. 1). The diagnosis of acute tubular necrosis was retained. The patient's renal function recovered spontaneously, 1.24 mg/dL 3 weeks later and 1.07 mg/dL 5 weeks later.

AKI secondary to near-drowning is not uncommon, but the resultant severe AKI requiring dialysis is exceedingly rare: we found only 7 reported cases, including the present report (6-10). The two other cases were related with rhabdomyolysis (7, 8), 1 case resulted from hypothermia (9), 1 case were related with both (10), and 2 cases had isolated AKI (6). Isolated AKI was first described by Spicer et al. in 1999 (6); usually the term means that disproportionately severe AKI even several days after the immersion episode who did not require cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) or did not experience shock, hypothermia or myoglobinuria after their near-drowning. This case is the third report of severe isolated AKI in the literature and first report in Korea. Immersion and drowning injury has been widely reviewed (1-3), and widespread tissue hypoxia and subsequent reperfusion injury are thought to be the predominant underlying pathophysiology, although hypovolemia and hypothermia may also contribute to tissue damage. The initial event leading to tissue injury in kidney ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI) is the acute reduction of blood flow that produces hypoxia-induced vascular and tubular dysfunction. Following reperfusion, various intracellular events occur that lead to cellular dysfunction, apoptosis and cell death (11). The morphological changes occur mainly in proximal tubules, susceptible to ischemic injury, including loss of polarity, loss of the brush border (12), and redistribution of integrins and Na+/K+-ATPase to the apical surface (13). Calcium (14) and reactive oxygen species (15) may also have a role in these morphological changes, in addition to subsequent cell death resulting from necrosis and apoptosis. Both viable and nonviable cells are shed into the tubular lumen, resulting in the formation of casts and luminal obstruction and contributing to the reduction in the GFR (16). Inflammation is also an important early event leading to intracellular responses that ultimately result in apoptosis and necrosis. The involvement of the immune system in kidney IRI is very complex; dendritic cells and macrophages may contribute early in the innate immune response to kidney IRI and promote neutrophil infiltration (17), while T regulatory cells have been shown to suppress the extent of kidney IRI through an IL-10 dependent mechanism (18). Dendritic cells, neutrophils, phagocytic macrophages and lymphocytes participate in the early phase of kidney IRI as well as the late reparative phase (19). A retrospective study to assess clinical predictors of near-drowning associated AKI concluded that lymphocytosis may also predict renal impairment (6). In our case, the patient had not lymphocytosis but mild lymphocyte infiltration in interstitium was seen.

Metabolic acidosis is common after near-drowning, and is due to lactic acidosis induced by tissue hypoxia (5, 20). That lactate was the probable cause of acidosis supported by the increased anion gap and reversible nature of the acidosis. In this case, unfortunately, serum level of lactic acid and arterial blood gas analysis just after immersion episode were not checked, but severe high anion gap metabolic acidosis was seen on presentation. The acidosis was quickly corrected, but the initial mild renal dysfunction progressed to establish severe AKI and required supportive dialysis. It is very similar to previous case reports of isolated AKI (6). Why renal injury predominates in the absence of other post-immersion injury sequelae is not known. The possible explanation is renin-angiotensin surge when returning to dry land after whole-body immersion may play a role (3). Although the pathology of isolated AKI is controversial, renal hypoxia and subsequent reperfusion injury play major role in developing severe AKI due to ATN in our case. It is plausible that the patient had not hemodynamic instability, hypothermia or rhabdomyolysis that related with AKI after near-drowning.

In summary, we describe a case of severe isolated AKI caused by near-drowning. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first such case report in Korea. Our case differs from the 2 other cases we reviewed in the literature in that our patient's AKI was confirmed by kidney biopsy as ATN. Although near-drowning associated AKI is usually mild and self-limited, severe AKI required dialysis can occur even several days after immersion event, it is recommended that any patient who presents after near-drowning or immersion should be assessed for potential AKI.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Levin DL, Morriss FC, Toro LO, Brink LW, Turner GR. Drowning and near-drowning. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1993. 40:321–336.

2. Oakes DD, Sherck JP, Maloney JR, Charters AC 3rd. Prognosis and management of victims of near-drowning. J Trauma. 1982. 22:544–549.

3. Pearn J. Pathophysiology of drowning. Med J Aust. 1985. 142:586–588.

4. Layon AJ, Modell JH. Drowning: update 2009. Anesthesiology. 2009. 110:1390–1401.

5. Hoff BH. Multisystem failure: a review with special reference to drowning. Crit Care Med. 1979. 7:310–320.

6. Spicer ST, Quinn D, Nyi Nyi NN, Nankivell BJ, Hayes JM, Savdie E. Acute renal impairment after immersion and near-drowning. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999. 10:382–386.

7. Bonnor R, Siddiqui M, Ahuja TS. Rhabdomyolysis associated with near-drowning. Am J Med Sci. 1999. 318:201–202.

8. Vega J, Gutiérrez M, Goecke H, Idiáquez J. Renal failure secondary to effort rhabdomyolysis: report of three cases. Rev Med Chil. 2006. 134:211–216.

9. Hottelart C, Diaconita M, Champtiaux B, Soulis F, Aldigier JC. When the kidney catches a cold: an unusual cause of acute renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004. 19:2421–2422.

10. Park JS, Kim JH, Gil HW, Yang JO, Lee EY, Hong SY. A case of acute kidney injury after seawater immersion. Korean J Nephrol. 2010. 29:247–249.

11. Schrier RW, Wang W, Poole B, Mitra A. Acute renal failure: definitions, diagnosis, pathogenesis, and therapy. J Clin Invest. 2004. 114:5–14.

12. Thadhani R, Pascual M, Bonventre JV. Acute renal failure. N Engl J Med. 1996. 334:1448–1460.

13. Alejandro VS, Nelson WJ, Huie P, Sibley RK, Dafoe D, Kuo P, Scandling JD Jr, Myers BD. Postischemic injury, delayed function and Na+/K+-ATPase distribution in the transplanted kidney. Kidney Int. 1995. 48:1308–1315.

14. Kribben A, Wieder ED, Wetzels JF, Yu L, Gengaro PE, Burke TJ, Schrier RW. Evidence for role of cytosolic free calcium in hypoxia-induced proximal tubule injury. J Clin Invest. 1994. 93:1922–1929.

15. Yaqoob M, Edelstein CL, Schrier RW. Role of nitric oxide and superoxide balance in hypoxia-reoxygenation proximal tubular injury. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1996. 11:1738–1742.

16. Devarajan P. Update on mechanisms of ischemic acute kidney injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006. 17:1503–1520.

17. Li L, Huang L, Sung SS, Vergis AL, Rosin DL, Rose CE Jr, Lobo PI, Okusa MD. The chemokine receptors CCR2 and CX3CR1 mediate monocyte/macrophage trafficking in kidney ischemia-reperfusion injury. Kidney Int. 2008. 74:1526–1537.

18. Kinsey GR, Sharma R, Huang L, Li L, Vergis AL, Ye H, Ju ST, Okusa MD. Regulatory T cells suppress innate immunity in kidney ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009. 20:1744–1753.

19. Li L, Okusa MD. Macrophages, dendritic cells, and kidney ischemia-reperfusion injury. Semin Nephrol. 2010. 30:268–277.

20. Modell JH, Davis JH. Electrolyte changes in human drowning victims. Anesthesiology. 1969. 30:414–420.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download