Abstract

Korean Red Ginseng (KRG) is a functional food and has been well known for keeping good health due to its anti-fatigue and immunomodulating activities. However, there is no data on Korean red ginseng for its preventive activity against acute respiratory illness (ARI). The study was conducted in a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial in healthy volunteers (Clinical Trial Number: NCT01478009). Our primary efficacy end point was the number of ARI reported and secondary efficacy end point was severity of symptoms, number of symptoms, and duration of ARI. A total of 100 volunteers were enrolled in the study. Fewer subjects in the KRG group reported contracting at least 1 ARI than in the placebo group (12 [24.5%] vs 22 [44.9%], P = 0.034), the difference was statistically significant between the two groups. The symptom duration of the subjects who experienced the ARI, was similar between the two groups (KRG vs placebo; 5.2 ± 2.3 vs 6.3 ± 5.0, P = 0.475). The symptom scores were low tendency in KRG group (KRG vs placebo; 9.5 ± 4.5 vs 17.6 ± 23.1, P = 0.241). The study suggests that KRG may be effective in protecting subjects from contracting ARI, and may have the tendency to decrease the duration and scores of ARI symptoms.

Acute respiratory illness (ARI) is a self-limiting viral disease that causes mild symptoms such as fever, shivering, chills, malaise, and dry cough. Rhinovirus and coronavirus (50%-70%) are the most common viruses, followed by influenza virus (20%-35%), and adenovirus (5%-10%) (1, 2). Most influenza-associated deaths occur in persons aged 65 yr or older with associated chronic disease (3). Vaccination to prevent influenza is particularly important for elderly persons who are at an increased risk for severe complications from influenza (4).

Dietary supplements represent the most rapidly growing segment of the market and their use range from the treatment and prevention of common illnesses to cancer treatment and prevention (5, 6). A well-designed study to evaluate the effectiveness of dietary supplements on reduction of the severity of symptoms and duration of upper respiratory tract infections has not been approved to date (6).

Korea red ginseng (KRG) is commercially available 4 to 6-yr old Panax ginseng root that has been steamed unpeeled and dried to prepare light yellow-brown, or light red-brown ginseng. During its manufacturing process, thirteen kinds of active ingredients characteristic of red ginseng were obtained as some partly deglycosylated saponins. This process is conducted to store red ginseng longer and to increase its medicinal efficacies.

Recently, KRG was shown to be capable of enhancing cell-mediated immune responses by T lymphocytes and activating natural killer cells in immunomodulation and anticancer pathways. Two clinical studies for the immune response with ginseng or KRG have been conducted (7-9). In addition, treatment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia in rats with ginseng was found to reduce bacterial load and lung pathology, as well as to increase immunoglobulin G2a in serum. They suggest that the antimicrobial properties of ginseng are due to its induction of Th1-like responses (10).

Other studies have shown that taking American ginseng extract as a prophylaxis during the influenza season in older adults reduced the incidence of acute respiratory illness in vaccinated (11) and non-vaccinated subjects (12, 13). These results suggest that ginseng extract was effective for the prevention of upper respiratory illnesses caused by various viruses.

Until now, ginseng has been well known for improving general quality-of-life, for exhibiting immuonmodulating effects, and for antidiabetic effects (14-18). However, there has been no data accumulated Korean red ginseng for its preventive activity against ARI, as has shown in American ginseng. In this study, to investigate the effectiveness of KRG for its preventive activity against ARI, we administered KRG and placebo to healthy volunteers for 12 weeks.

This study was a 12 weeks, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial at the onset of the influenza season at the Chonbuk National University Hospital (Fig. 1). Subjects who responded and met the inclusion criteria during a telephone screening interview were scheduled for a baseline visit. The evaluation included a physical examination, electrocardiogram, and screening blood parameter study. In addition, subjects were scheduled for a screening visit (within 3 weeks) where the informed consent was reviewed and signed. A random number between 1 and 100 was generated by a computer for each subject. The randomization codes were hidden from all subjects, research staff, investigators and pharmacists until all the data were analyzed.

The enrolled subjects were scheduled for the first visit, and subjects were randomly assigned to one of two groups, the concentrated red ginseng (n = 50) or placebo (n = 50) group. The prescription of the study products were 1.0 g 3 times a day (3.0 grams per day) for 12 weeks. Placebos were made with the same taste and appearance but without the principal ingredients that present in the red ginseng extract. The study products were provided to subjects every 4 weeks.

During the intervention period of 12 weeks, subjects were asked to continue their usual diets and activity and were asked not to take any other functional foods or dietary supplements. Anthropometric, biochemical parameters, and vital signs were measured before and after the intervention period for both groups. Every fourth week, the subjects were asked to report for assessment of any adverse events or any changes in training, lifestyle, or eating patterns and to assess the compliance. The mercury thermometer was used to check body temperature in their places.

The study subjects were recruited between October to November 2010 in Clinical Trial Center for Functional Foods via a local newspaper advertisement. A total of 115 volunteers who responded to the advertisements were pre-screened via telephone interview and screened for the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The study subjects were required to be in good general health, between 30 and 70 yr of age. To avoid the confounding effects of vaccination, subjects were excluded if they had been vaccinated against influenza within 6 months. Other exclusion criteria for the study were: 1) HIV infected or cancer patients; 2) cardiovascular disease, neurologic or psychiatric disease, and renal, pulmonary and hepatic abnormalities; 3) upper respiratory infection within two weeks prior to the study; 4) active tuberculosis treated; 5) history of disease that could interfere with the test products or impede their absorption, such as gastrointestinal disease (Crohn's disease) or gastrointestinal surgery (a appendicitis or enterocele surgery were included); 6) participation in any other clinical trials within the past 2 months; 7) abnormal liver function test (ALT > 60 IU/L); 8) connective tissue disease patients; 9) multiple sclerosis disease patients; 10) taking medications such as immunosuppressive drugs, corticosteroids, warfarin, phenelzine, pentobarbital, haloperidol, cyclosporine; 11) allergic or hypersensitive to ginseng; 12) antipsychosis drugs therapy within the past 2 months; 13) laboratory tests, and medical or psychological conditions deemed by the investigators to interfere with successful participation in the study; 14) history of alcohol or substance abuse; 15) pregnancy or breast feeding; and 16) being judged by the responsible physician of the local study center as unfit to participate in the study.

Korean red ginseng was produced by the process of steaming and drying from fresh ginseng cultivated in Jinan-Gun, Korea. The standardized red ginseng (Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer) extract was obtained through an industrial process under the strict quality control. Namely, fresh ginseng was steamed for 2 to 3 hr at 95℃ and dried under the sun or with hot air. After ethanol extract (90℃, 24 hr, 70% ethanol solution) was made in a highly concentrated form to give a 60% or more solid content. The sum of ginsenosides Rg1 and Rb1, used as quality control marker, was above 7 mg/g. Placebo was made to maintain in its flavor and taste of red ginseng extract, and also contained 30% hop extracts and 45% soybean oil. Red ginseng extract and placebo were both prepared at the CheonJiYang Co. Ltd., Seoul, Korea.

The ARI defined by following symptoms; fever (temperature > 38.0℃), cough, sore throat, nasal congestion, or body aches in the absence of a known cause other than influenza. The primary efficacy end point was the frequency rate of ARI. The secondary end point included 1) the frequency rate of each clinical symptoms such as fever, rhinorrhea, nasal congestion, sore throat, cough, sputum, dyspnea, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, headache, and myalgia 2) symptom duration; and 3) severity of symptom (total symptom score).

This assessment was conducted by telephone weekly or self-reported during the intervention period. The symptom score was average, and the range was from 0 to 3. All subjects were asked to complete a daily log at about the same time every morning to document the severity of their influenza-related symptoms on a 4-point scale sheet (0 = no symptom, 1 = mild symptom, 2 = moderate symptom and 3 = severe symptom) (6, 12). The total number of days of symptoms was calculated through telephone interviews every day until the symptoms disappeared. Safety assessments were in the case of adverse events, and included laboratory tests (hematology, biochemistry, and urinalysis) and vital sign assessments (systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and pulse rate).

Statistical analysis was done by a statistician under blinded conditions. The efficacy analysis was done only with subjects who completed the study (per protocol, PP group), whereas the frequency rate of ARI was done using the Fisher's exact test. Symptom duration and score were analyzed with the Mann Whitney U test and Fisher's exact test. The safety assessment was also done only with subjects that completed the study (per protocol, PP group), and the analysis between the two groups were done using the Mann Whitney U test and Fisher's exact test. We used the repeated measure analysis of variance (ANOVA) to compare the laboratory findings between two groups before and after clinical trial. SPSS software ver 19.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for all analyses and P values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

All subjects gave their written, informed consent before entering the study, which was conducted in accordance with the international conference on harmonization guidelines for good clinical practice and was approved by the functional foods institutional review board of Chonbuk National University Hospital (IRB number; IJRG-INFL-KRG, 2012-02-016).

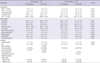

After screening, a total of 100 subjects were enrolled in this study and randomly assigned to the KRG and placebo group (male 38, female 62). During the study period, 2 subjects failed to complete the study (KRG 1, placebo 1) (Fig. 2). The mean age of subjects was 46.0 ± 9.0 yr old (KRG group 45.5 ± 8.3, placebo 46.6 ± 9.6, P = 0.537). There were no significant differences in general characteristics of the study population between the two groups (Table 1). Alcohol and smoking was more frequent in the KRG group, but there were no significant differences between the two groups (P = 0.110, P = 0.059).

The total number of prescribed capsules was 768.6 ± 30.9 (P = 0.141) and total intakes were 727.4 ± 55.8 (P = 0.888), which was not significant between the two groups. Compliance reported taking more than 75% of the medication was high in both groups; 95.2 ± 4.7% in KRG, 94.0 ± 7.2% in placebo group. No subject failed to complete the study due to under compliance (Table 2). Blinding was also maintained adequately during the study period. After the study, 26.7% of those taking KRG and 21.3% of those taking placebo thought they had been given the KRG.

During the study period, subjects who experienced ARI at least one time were 34 in total (Table 3). In these, KRG and placebo was 12 (24.5%), and 22 (44.9%), respectively. The frequency of ARI in the KRG group was lower than in the placebo group and these findings were statistically significant (P = 0.034). In this study, the absolute risk reduction that absolute rate difference between two groups was 20.4% (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.6%-37.4%) and the relative risk reduction which means that giving KRG reduces the ARI was 45.5% (95% CI, 2.5%-69.5%).

Among the 34 subjects that experienced ARI, the symptom duration was 5.2 ± 2.3 day in the KRG group and 6.3 ± 5.0 day in the placebo group (P = 0.475). The symptom duration in the KRG group was short, but there was no statistical difference between the two groups (Table 3). The symptom score (KRG 9.5 ± 4.5 vs placebo 17.6 ± 23.1) was lower in the KRG group than in the placebo group. However, no statistical significance was observed (P = 0.241). Among the symptoms, the frequency rate of cough (P = 0.045) in the KRG group was significantly lower than in the placebo group. The nasal congestion (P = 0.064) and headache (P = 0.059) in the KRG group was lower than in the placebo group, which was marginally significant.

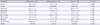

There was no statistical difference between the two groups for adverse events and specific severe adverse events were not observed during the study period (P = 0.378) (Table 4). The laboratory findings for safety, which included hematology, biochemistry, and urinalysis, was not statistical difference between the two groups (Table 5). Supplementary medications, particulary NSAIDs, were used by 10.2% (5/49) and 16.3% (8/49) of the subjects in the KRG and placebo groups, respectively (P = 0.372). Antibiotics (placebo vs KRG, 18.4% vs 6.1%, P = 0.064), and anti-histamine (placebo vs KRG, 12.2% vs 4.1%, P = 0.004) were used for colds and flu respectively. The differences in the incidence of NSAIDs usage between the two groups were not found to be statistically significant. The incidence of antibiotics usage was marginally more common in the placebo than in the KRG group. Anti-histamine usage was significantly more common in the placebo than in the KRG group.

The frequency rate of ARI was significantly lower in the KRG group than in the placebo group in this study. The symptom duration was short and the symptom score was lower in KRG group than placebo group. However, the statistical significance was not observed. Regarding the safety of KRG, there were no specific clinical and laboratory side effects after 12 weeks for the healthy subjects.

In the process of steaming and drying for manufacturing red ginseng, it occurs various chemical reactions that eventually lead to the production of effective components, not found in fresh ginseng. And also, the effective absorption and digestion of various active compounds are considered to be the strength of red ginseng. Red ginseng was shown to have a various immunomodulatory actions such as activation of natural killer cells, inhibitory action of food allergy, antagonistic reaction for immunosuppressive agents, and activation of innate immunity (14-16, 19-22). It has been proven to have a broad range of biological activities including T-cell mediated immune reaction, as well as antioxidant and anti-tumor actions (7, 8, 23, 24). Recently, Kim et al. (14) reported the effect of oral administration of KRG on influenza A (H1N1) virus infection. In the study, they investigated the inhibitory effect of KRG extract on plaque formation by influenza A virus in a cell-based plaque assay, and the effect of orally administered KRG on influenza A virus infection in mice. They suggested that KRG could potentially be used as a complementary treatment of influenza A virus. Kaneko and Nakanishi (25) performed a retrospective study of long term use of KRG in the staff of geriatric hospital. They also reported that KRG has preventive effects on the common cold symptom complex, including flu. However, there was no well designed clinical trial regarding the effect of ARI for KRG.

McElbaney et al. (11) compared American ginseng with a placebo in preventing acute respiratory illness in an institutional setting during influenza seasons. In their study, the mean age of volunteers was over 80 yr old, 74% female, and approximately 90% had received influenza vaccine in each of the 2 yr. Confirmation of viral acute respiratory illness was conducted by culture or serology for influenza. They showed that the incidence of laboratory confirmed influenza illness was lower in American ginseng groups than in placebo groups (odds ratio [OR], 0.14; 95% CI, 0.02-0.97). Combined data for laboratory confirmed influenza illness and respiratory syncytial virus illness (OR, 0.11; 95% CI, 0.01-0.86) were also lower in American ginseng study groups than in placebo groups. This suggests that American ginseng is potentially effective for preventing acute respiratory illness. Predy et al. (12, 26) performed a clinical trial that was very similar to our study. The mean age of volunteers was 43, 60% female, and subjects were excluded if they had been vaccinated against influenza in the previous 6 months. The mean number of colds per person was lower in the ginseng group than in the placebo group (ginseng vs placebo, 0.68% vs 0.82%, 95% CI, 0.04-0.45). The proportion of subjects with 2 or more Jackson-verified colds (ginseng vs placebo, 10.0% vs 22.8%, P = 0.004) was significantly lower in the ginseng group than in the placebo group, as were the total symptom score (ginseng vs placebo, 77.5 vs 112.3, P = 0.002), and the total number of days that cold symptoms were reported (ginseng vs placebo, 10.8 vs 16.5, P < 0.001). These results showed that American ginseng had protective effects for ARI. However, the effect of KRG on ARI has not been studied although it is known to have a broad range of biological activities and effect of KRG on influenza A (H1N1) virus infection. In this study, we showed that KRG has a significant protective effect for ARI and decreases the symptom duration and symptom score similar to American ginseng.

Herbal medicine, together with the declining numbers of new antimicrobials that are being certified and introduced into clinical practice, is one of the fastest growing alternative therapies. The uses of herbal medication range from the treatment and prevention of common illnesses to cancer treatment and prevention (5, 6). Most herbal medicine or dietary supplements appear to be safe, and the medical literature supports their effectiveness for certain conditions (5). Among them, ginseng is one of the most well studied herbal medicines. KRG has a broad range of activity as well as protective effect against ARI, and hence is potentially more effective in combating different emerging strains of virus.

In our study, anti-histamine and antibiotics were used more frequently in the placebo group compared to the KRG group.

There are several limitations in this study. First, we did not calculate the number of subjects statistically because this was a preliminary study. We need more extensive clinical studies with clear statistical numberings. Second, we did not conduct microbiological analysis of ARI. Therefore we are not certain of the nature of the virus or the number of strains. Third, we included only healthy volunteers without influenza vaccinations. Clinical trials on healthy volunteers with influenza vaccination vs without vaccination and various age groups are required.

In conclusion, KRG have a protective effect against contracting ARI, and may have a tendency to decrease the duration and scores of ARI symptoms. However, we need further studies with statistically powered subjects and children, vaccinated subjects, and immuonocompromised subjects.

Figures and Tables

Table 4

Adverse events during the study period between the Korean red ginseng (KRG) and the placebo groups

Table 5

The laboratory findings for safety after the duration of the clinical trial

Variables were presented as number (percentage) and mean ± SD. *Analyzed by repeated measure ANOVA and the P value means the significant level between KRG group and placebo group. WBC, white blood cell; RBC, red blood cell; PLT, platelet; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; AST, aspartate transaminase; ALT, alanine transaminase; γ-GT, gamma glutamyl transferase; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; HPF, high power field.

References

1. Turner RB. Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, editors. The common cold. Principles and practice of infectious disease. 2010. Volume 1:7th ed. London: Chruchill Livingstone/Elsevier;809–813.

2. Rubin MA, Sande MA. Fauci AS, Braunwald E, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, Loscalzo J, editors. Pharyngitis, sinusitis, otitis, and other upper respiratory tract infectiions. Harrison's principles of internal edicine. 2008. 17th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill;205–214.

3. Thompson WW, Shay DK, Weintraub E, Brammer L, Cox N, Anderson LJ, Fukuda K. Mortality associated with influenza and respiratory syncytial virus in the United States. JAMA. 2003. 289:179–186.

4. Fiore AE, Uyeki TM, Broder K, Finelli L, Euler GL, Singleton JA, Iskander JK, Wortley PM, Shay DK, Bresee JS, et al. Prevention and control of influenza with: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010. 59:1–62.

5. Eliason BC, Kruger J, Mark D, Rasmann DN. Dietary supplement users: demographics, product use, and medical system interaction. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1997. 10:265–271.

6. Yale SH, Liu K. Echinacea purpurea therapy for the treatment of the common cold: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Arch Intern Med. 2004. 164:1237–1241.

7. Bae EA, Hyun YJ, Choo MK, Oh JK, Ryu JH, Kim DH. Protective effect of fermented red ginseng on a transient focal ischemic rats. Arch Pharm Res. 2004. 27:1136–1140.

8. Scaglione F, Cattaneo G, Alessandria M, Cogo R. Efficacy and safety of the standardised Ginseng extract G115 for potentiating vaccination against the influenza syndrome and protection against the common cold. Drugs Exp Clin Res. 1996. 22:65–72.

9. Yun TK, Lee YS, Lee YH, Kim SI, Yun HY. Anticarcinogenic effect of Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer and identification of active compounds. J Korean Med Sci. 2001. 16:S6–S18.

10. Song Z, Johansen HK, Faber V, Moser C, Kharazmi A, Rygaard J, Høiby N. Ginseng treatment reduces bacterial load and lung pathology in chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia in rats. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997. 41:961–964.

11. McElhaney JE, Gravenstein S, Cole SK, Davidson E, O'neill D, Petitjean S, Rumble B, Shan JJ. A placebo-controlled trial of a proprietary extract of North American ginseng (CVT-E002) to prevent acute respiratory illness in institutionalized older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004. 52:13–19.

12. Predy GN, Goel V, Lovlin R, Donner A, Stitt L, Basu TK. Efficacy of an extract of North American ginseng containing poly-furanosyl-pyranosylsaccharides for preventing upper respiratory tract infections: a randomized controlled trial. CMAJ. 2005. 173:1043–1048.

13. McElhaney JE, Goel V, Toane B, Hooten J, Shan JJ. Efficacy of COLD-fX in the prevention of respiratory symptoms in community-dwelling adults: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo controlled trial. J Altern Complement Med. 2006. 12:153–157.

14. Kim JY, Kim HJ, Kim HJ. Effects of oral administration of Korean red ginseng on influenza A (H1N1) virus infection. J Ginseng Res. 2011. 35:104–110.

15. Quan FS, Compans RW, Cho YK, Kang SM. Ginseng and Salviae herbs play a role as immune activators and modulate immune responses during influenza virus infection. Vaccine. 2007. 25:272–282.

16. Wang M, Guilbert LJ, Ling L, Li J, Wu Y, Xu S, Pang P, Shan JJ. Immunomodulating activity of CVT-E002, a proprietary extract from North American ginseng (Panax quinquefolium). J Pharm Pharmacol. 2001. 53:1515–1523.

17. Caso Marasco A, Vargas Ruiz R, Salas Villagomez A, Begoña Infante C. Double-blind study of a multivitamin complex supplemented with ginseng extract. Drugs Exp Clin Res. 1996. 22:323–329.

18. Ha TS, Choi JY, Park HY, Lee JS. Ginseng total saponin improves podocyte hyperpermeability induced by high glucose and advanced glycosylation endproducts. J Korean Med Sci. 2011. 26:1316–1321.

19. Kim JY, Germolec DR, Luster MI. Panax ginseng as a potential immunomodulator: studies in mice. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 1990. 12:257–276.

20. Hu S, Concha C, Johannisson A, Meglia G, Waller KP. Effect of subcutaneous injection of ginseng on cows with subclinical Staphylococcus aureus mastitis. J Vet Med B Infect Dis Vet Public Health. 2001. 48:519–528.

21. Luo YM, Cheng XJ, Yuan WX. Effects of ginseng root saponins and ginsenoside Rb1 on immunity in cold water swim stress mice and rats. Zhongguo Yao Li Xue Bao. 1993. 14:401–404.

22. Sumiyoshi M, Sakanaka M, Kimura Y. Effects of Red Ginseng extract on allergic reactions to food in Balb/c mice. J Ethnopharmacol. 2010. 132:206–212.

23. Block KI, Mead MN. Immune system effects of echinacea, ginseng, and astragalus: a review. Integr Cancer Ther. 2003. 2:247–267.

24. Keum YS, Park KK, Lee JM, Chun KS, Park JH, Lee SK, Kwon H, Surh YJ. Antioxidant and anti-tumor promoting activities of the methanol extract of heat-processed ginseng. Cancer Lett. 2000. 150:41–48.

25. Kaneko H, Nakanishi K. Proof of the mysterious efficacy of ginseng: basic and clinical trials: clinical effects of medical ginseng, Korean red ginseng: specifically, its anti-stress action for prevention of disease. J Pharmacol Sci. 2004. 95:158–162.

26. Nguyen A, Slavik V. COLD-fX. Can Fam Physician. 2007. 53:481–482.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download