Abstract

Congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) is characterized by decreased adrenal hormone production due to enzymatic defects and subsequent rise of adrenocorticotrophic hormone that stimulates the adrenal cortex to become hyperplastic, and sometimes tumorous. As the pathophysiology is basically a defect in the biosynthesis of cortisol, one may not consider CAH in patients with hypercortisolism. We report a case of a 41-yr-old man with a 4 cm-sized left adrenal tumorous lesion mimicking Cushing's syndrome who was diagnosed with CAH. He had central obesity and acanthosis nigricans involving the axillae together with elevated 24-hr urine cortisol level, supporting the diagnosis of Cushing's syndrome. However, the 24-hr urine cortisol was suppressed by 95% with the low dose dexamethasone suppression test. CAH was suspected based on the history of precocious puberty, short stature and a profound suppression of cortisol production by dexamethasone. CAH was confirmed by a remarkably increased level of serum 17-hydroxyprogesterone level. Gene mutation analysis revealed a compound heterozygote mutation of CYP21A2 (I173N and R357W).

Congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) is a common autosomal recessive disorder. Steroid 21-hydroxylase deficiency accounts for over 90% of CAH cases and can have diverse manifestations: from the salt-wasting to the non-classical form due to a highly variable genetic mutation (1, 2). In the case of the simple virilizing or non-classical form, the symptoms related to the enzyme deficiency may be so insidiously progressive that it is not easy to identify the disease. Impaired negative feedback by reduced cortisol causes an exaggerated rise of adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH) levels, which stimulates the adrenal cortex to become hyperplastic, and sometimes nodular or tumorous (3-5). If we encounter a patient with adrenal incidentaloma(s), we may consider a variety of adrenal diseases, such as Cushing's syndrome or CAH (6); however, the two conditions are mutually exclusive with regard to cortisol production. Here, we present a case of CAH mimicking Cushing's syndrome.

A 41-yr-old man was referred to our emergency room from a local clinic on July 3, 2006, with the impression of acute viral hepatitis due to a remarkable elevation of liver enzymes. He had experienced generalized weakness, dark urine, and jaundice for a two week period. His previous history included community-acquired pneumonia and carpal tunnel syndrome, but neither diabetes mellitus nor hypertension. He complained of impotence, and his mother described precocious puberty and hirsutism beginning at the age of 7. He was not married and had no children.

His vital signs were a blood pressure of 115/92 mmHg, a regular pulse of 105/min, and a respiratory rate of 18/min. His height was 152.5 cm (< 3th percentile) and body weight was 72.5 kg. The body mass index was 32.5. Acanthosis nigricans was present in both axillae, and there was central obesity with erythematous, scaly, guttate papules on the lower abdominal skin. He also had a rather ambiguous buffalo hump; however, moon face or red stria was not present (Fig. 1).

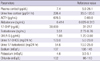

Total and direct bilirubin levels were elevated at 11.6 mg/dL and 8.6 mg/dL, respectively. The AST and ALT levels were 224 and 1,044 U/L, respectively. Serum BUN level was 9.7 mg/dL, and serum creatinine level was 0.82 mg/dL. Serum electrolytes were normal. Based on a positive anti-HAV IgM titer, he was diagnosed with acute hepatitis A. During the evaluation to exclude other causes of liver dysfunction, a 4 × 2.3 cm left adrenal mass and bilateral adrenal hyperplasia were incidentally noted on abdominal CT (Fig. 2A, B). We evaluated the endocrine function (Table 1). Twenty-four hour urine catecholamines and VMA were within the normal range. However, hypercortisoluria was noted in 2 independent measurements (226.4 µg/24 hr; 122.1 µg/24 hr). Plasma cortisol was within the normal range (7.4 µg/dL), however, ACTH level was very high (676.5 pg/mL). Urine 17-OHCS and 17-ketosteroid levels were markedly elevated to 123.0 mg/24 hr and 54.6 mg/24 hr, respectively. Serum aldosterone level was marginally elevated (0.414 ng/mL). DHEA-S was within the normal range (1.88 µg/mL). Based on the high serum ACTH level, hypercortisoluria, and bilateral adrenal hyperplasia with a large left adrenal mass, we suspected a pituitary corticotrophic adenoma with marked asymmetric adrenal hyperplasia. To confirm the diagnosis of Cushing's syndrome, low- and high-dose dexamethasone suppression tests were performed. Then, 24-hr urine cortisol was markedly suppressed, not only by high-dose dexamethasone but also by low-dose dexamethasone (Table 2); this result essentially eliminates the diagnosis of Cushing's syndrome (7, 8). We thus suspected CAH based on the short stature, precocious pubarche and marked suppression of 24-hr urine cortisol by dexamethasone suggesting hyperresponsiveness of the adrenal cortex to ACTH. The testosterone level was normal (3.51 ng/mL), but 17α-hydroxyprogesterone (17-OHP) was markedly elevated to 30,000 ng/dL, strongly supporting the diagnosis of a simple virilizing form of CAH. Gene analysis revealed CAH due to 21-hydroxylase deficiency by a compound heterozygote for CYP21 mutations: Ile173Asn (I173N) and Arg357Trp (R357W) (Fig. 3), confirming the diagnosis of a simple virilizing from of CAH due to mutations in CYP21.

We began administration of adrenal steroids. After 6 months of treatment with dexamethasone (0.25 mg daily), bilateral adrenal hyperplasia and tumorous growth in left adrenal gland were substantially decreased in size (Fig. 2C, D). 17-OHP and ACTH levels were normalized to 118 ng/dL and 20.8 pg/mL, respectively, and impotence was improved.

Blood samples were obtained in the morning after an overnight fast and a 30-min resting period in the supine position. Hormones were assayed using IRMA kits. For low- or high-dose dexamethasone suppression test, 0.5 or 2 mg dexamethasone was administered 4 times a day for 2 consecutive days.

Genomic DNA was extracted from the peripheral blood leukocytes of patient by using the Wizard Genomic DNA Purification Kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). All exons of the CYP21 gene were amplified by PCR on a thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Direct sequencing was performed using the BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction kit and an ABI Prism 3130 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). The sequences were analyzed using the Sequencer program (Gene Codes Corp., Ann Arbor, MI, USA) and were compared to the reference sequences. The numbering of nucleotide positions was done according to the CYP21 DNA sequence, and the Gen-Bank accession number was NM000500.

It is not rare to find adrenal incidentalomas in patients with CAH. The 21-hydroxylase deficiency is considered to be a predisposing factor for adrenocortical tumorigenesis because an increased response of 17-OHP to exogenous ACTH stimulation has been seen in a large proportion of patients with adrenal incidentalomas (3-5, 9). Some studies have reported that tumor size and an augmented 17-OHP response to ACTH stimulation were significantly correlated in the subjects with impaired 21-hydroxylase deficiency (5, 9). This tumor-associated phenomenon can be explained by chronic stimulation of the adrenal cortex by an elevated ACTH concentration secondary to the reduced 21-hydroxylase reserve. However, as CAH is basically a condition of cortisol insufficiency, CAH may not be considered in patients with adrenal incidentalomas and hypercortisolism.

In the beginning, we also did not consider the diagnosis of CAH because biochemical tests showed elevated urine cortisol level in 2 separate measurements and the patient had clinical evidences suggesting hypercortisolism such as buffalo hump or acanthosis nigricans. However, low-dose dexamethasone test clearly showed that this case is not consistent with the diagnosis of Cushing's syndrome. In fact, suppression of urine cortisol by low-dose dexamethasone was remarkably high (> 95% suppression), which may suggest the hyperresponsiveness of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis to dexamethasone. In search for conditions showing hypercortisolism, adrenal tumor and normal-to-increased responsiveness of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis, we noticed that this patient has an extreme short stature (< 3th percentile) and precocious puberty which may suggest the diagnosis of the virilizing type of CAH. In fact, hyperresponsiveness of the adrenal gland to ACTH or adrenal steroids is a characteristic feature of CAH (10). We suspected that urine cortisol level in CAH might be able to exceed upper normal limit on certain conditions if the adrenal gland that has become tumorous is chronically stimulated by ACTH (11, 12). Measurement of 17-OHP revealed that our suspicion was correct. Gene mutation analysis further corroborated our diagnosis of CAH, and this was similar to previous case heterozygote for a single mutation of CYP21 gene (13).

I173N is one of the most frequent specific point mutations in the simple virilizing form of 21-hydroxylase deficiency, and the R357W mutation is also well-known in the CYP21 gene. These two mutations are generated by intergenic recombination between the CYP21 and CYP21P genes, a frequent cause of 21-hydroxylase deficiency (14-18). According to previous studies, the I173N mutation is specifically associated with the simple virilizing phenotype because of a partial defect in activity. The R357W mutation is known to completely abolish enzymatic activity and, in its homozygous form, is associated with the salt-wasting phenotype (2). Disease severity in 21-hydroxylase deficiency is known to correlate with the less severely mutated allele. Our patient exhibited a simple virilizing phenotype because he had I173N mutation with a partial enzymatic defect in agreement with previous data (15-18).

In summary, we describe a case of CAH with adrenal tumorous lesion and hypercortisoluria mimicking Cushing's syndrome. Cortisol production in CAH may exceed the upper limit of normal production under stressed conditions as shown in this case. Unnecessary testing for differential diagnosis of Cushing's syndrome could be avoided if a detailed medical history was obtained from patient and 24-hr urine cortisol was measured in stable condition.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

General appearance of the patient. (A) In the face, features suggesting moon face was not observed. (B) In the axillae, acanthosis nigricans was seen. (C) In the posterior neck, buffalo hump-like elevation was found. (D) On his lower trunk, central obesity was noted. Erythematous, scaly, guttate papules were also seen.

Fig. 2

Adrenal CT images. (A & B) Bilateral adrenal hyperplasia (A) and tumorous growth in the left adrenal gland (B) were seen before treatment. (C & D) After 6 months of treatment with dexamethasone (0.25 mg per day), size of adrenal hyperplasia and tumorous lesion in left adrenal gland was markedly reduced (arrows, adrenal hyperplasia; arrow heads, tumorous growth in left adrenal gland).

Fig. 3

Gene analysis for 21-hydroxylase gene. Nucleotide sequence analysis of the CYP21 gene revealed that the patient was a compound heterozygote of 2 known mutations: I173N in exon 4 (A) and R357W in exon 8 (B).

References

1. Speiser PW, White PC. Congenital adrenal hyperplasia. N Engl J Med. 2003. 349:776–788.

2. White PC, Speiser PW. Congenital adrenal hyperplasia due to 21-hydroxylase deficiency. Endocr Rev. 2000. 21:245–291.

3. Bernini GP, Brogi G, Vivaldi MS, Argenio GF, Sgro M, Moretti A, Salvetti A. 17-Hydroxyprogesterone response to ACTH in bilateral and monolateral adrenal incidentalomas. J Endocrinol Invest. 1996. 19:745–752.

4. Bondanelli M, Campo M, Trasforini G, Ambrosio MR, Zatelli MC, Franceschetti P, Valentini A, Pansini R, degli Uberti EC. Evaluation of hormonal function in a series of incidentally discovered adrenal masses. Metabolism. 1997. 46:107–113.

5. Seppel T, Schlaghecke R. Augmented 17 alpha-hydroxyprogesterone response to ACTH stimulation as evidence of decreased 21-hydroxylase activity in patients with incidentally discovered adrenal tumours ('incidentalomas'). Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1994. 41:445–451.

6. Bornstein SR, Stratakis CA, Chrousos GP. Adrenocortical tumors: recent advances in basic concepts and clinical management. Ann Intern Med. 1999. 130:759–771.

7. Newell-Price J, Trainer P, Besser M, Grossman A. The diagnosis and differential diagnosis of Cushing's syndrome and pseudo-Cushings states. Endocr Rev. 1998. 19:647–672.

8. Orth DN. Cushing's syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1995. 332:791–803.

9. Toth M, Racz K, Glaz E. Increased plasma 17-hydroxyprogesterone response to ACTH in patients with nonhyperfunctioning adrenal adenomas is not due to a deficiency in 21-hydroxylase activity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998. 83:3756–3757.

10. Van Wyk JJ, Gunther DF, Ritzen EM, Wedell A, Cutler GB Jr, Migeon CJ, New MI. The use of adrenalectomy as a treatment for congenital adrenal hyperplasia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996. 81:3180–3190.

11. Gill GN. ACTH regulation of the adrenal cortex. Pharmacol Ther B. 1976. 2:313–338.

12. Janes ME, Chu KM, Clark AJ, King PJ. Mechanisms of adrenocorticotropin-induced activation of extracellularly regulated kinase 1/2 mitogen-activated protein kinase in the human H295R adrenal cell line. Endocrinology. 2008. 149:1898–1905.

13. Boronat M, Carrillo A, Ojeda A, Estrada J, Ezquieta B, Marin F, Novoa FJ. Clinical manifestations and hormonal profile of two women with Cushing's disease and mild deficiency of 21-hydroxylase. J Endocrinol Invest. 2004. 27:583–590.

14. Chiou SH, Hu MC, Chung BC. A missense mutation at Ile172----Asn or Arg356----Trp causes steroid 21-hydroxylase deficiency. J Biol Chem. 1990. 265:3549–3552.

15. Krone N, Braun A, Roscher AA, Knorr D, Schwarz HP. Predicting phenotype in steroid 21-hydroxylase deficiency? Comprehensive genotyping in 155 unrelated, well defined patients from southern Germany. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000. 85:1059–1065.

16. Stikkelbroeck NM, Hoefsloot LH, de Wijs IJ, Otten BJ, Hermus AR, Sistermans EA. CYP21 gene mutation analysis in 198 patients with 21-hydroxylase deficiency in The Netherlands: six novel mutations and a specific cluster of four mutations. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003. 88:3852–3859.

17. Torres N, Mello MP, Germano CM, Elias LL, Moreira AC, Castro M. Phenotype and genotype correlation of the microconversion from the CYP21A1P to the CYP21A2 gene in congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2003. 36:1311–1318.

18. Tukel T, Uyguner O, Wei JQ, Yuksel-Apak M, Saka N, Song DX, Kayserili H, Bas F, Gunoz H, Wilson RC, et al. A novel semiquantitative polymerase chain reaction/enzyme digestion-based method for detection of large scale deletions/conversions of the CYP21 gene and mutation screening in Turkish families with 21-hydroxylase deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003. 88:5893–5897.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download