Abstract

The risk factors related to hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection showed geographic and temporal differences. We investigated HCV-related risk factors in Korea where intravenous drug use (IVDU) is uncommon. The HCV-related risk factors were investigated in a prospective, multicenter chronic HCV cohort (n = 711) using a standardized questionnaire in four university hospitals. The results were compared with those of 206 patients with chronic liver diseases not related to either of HCV or hepatitis B virus infection (comparison group). The IVDU was found in 3.9% and remote blood transfusion (≥ 20 yr ago) in 18.3% in HCV cohort group, while that in comparison group was in none and 5.3%, respectively. In a multivariate logistic analysis, transfusion in the remote past (odds ratio [OR], 2.99), needle stick injury (OR, 4.72), surgery (OR, 1.89), dental procedures (OR, 2.96), tattooing (OR, 2.07), and multiple sexual partners (2-3 persons; OR, 2.14, ≥ 4 persons; OR, 3.19), were independent risk factors for HCV infection. In conclusion, the major risk factors for HCV infection in Korea are mostly related to conventional or alterative healthcare procedures such as blood transfusion in the remote past, needle stick injury, surgery, dental procedure, and tattooing although multiple sex partners or IVDU plays a minor role.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is one of the most common causes of chronic liver disease worldwide, affecting about 170 million people (1). HCV-infected patients are at risk for chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and they serve as a reservoir for HCV transmission. As there is no effective vaccine for HCV infection, finding risk factors and modes of HCV transmission has been the focus of elaborating the preventive strategies.

Significant geographic and temporal differences have been observed in the global epidemiology of HCV infection (2, 3). A lot of studies have reported on the risk factors of HCV infection in Western countries (1, 4, 5); however, studies in Asian countries, including Korea, are limited (6-8). Even in Asian countries, some differences in the risk factors related to HCV transmission have been observed. For example, traditional procedures such as acupuncture or other folk remedies are considered significant risk factors in Japan and Taiwan (9), while eyebrow tattooing for cosmetic purposes is an important risk factor for HCV infection in Vietnam and Cambodia (9).

In Korea, hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection has been a major cause of liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (10). However, the prevalence of HBV has gradually decreased along with successful universal immunization program (11, 12). Although the relative importance of HCV infection as a cause of liver disease has been increasing in Korea, studies on the risk factors related to HCV infection are very limited during the recent 10 yr. Although transfusion before 1992 was a strong factor for HCV transmission (13, 14), studies of HCV epidemiology with regard to other risk factors, such as injection drug use, needle stick injury, surgery, and tattooing have been limited in Korea (15-17).

The present study aimed to assess the risk factors for HCV infection in Korea by investigating the frequency of socio-demographic and behavioral factors in 711 patients with chronic HCV infection using data obtained from a prospective, multicenter cohort study, and to compare those factors in the cohort group with those in 206 patients with chronic liver diseases unrelated to HCV or hepatitis B virus infection (comparison group) at four university hospitals in Korea.

Data obtained from a prospective, multicenter cohort study were used for this study. The cohort included a total 711 adult patients with chronic HCV infection as confirmed by HCV RNA positivity for more than 6 months. They were enrolled in four university hospitals located in the Seoul metropolitan area of Korea (Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Asan Medical Center, Seoul St. Mary's Hospital, and Soonchunhyang University Bucheon Hospital) from January 2007 and to June 2010. The cohort was classified as 3 categories of HCV-related chronic liver disease; chronic hepatitis, liver cirrhosis, and HCC. Patients were excluded if they had acute liver diseases of any causes, such as acute viral hepatitis or toxic hepatitis, or past HCV infection with full recovery. As a comparison group, a total 206 patients with chronic liver diseases which were not caused by either HCV or HBV, and agreed to participate in this study, were separately enrolled at the same hospitals during the same study period.

A trained nurse at each hospital interviewed the subject patients using a standardized questionnaire, which included socio-demographics (age, gender, education, income, and occupation), health behaviors (smoking and drinking), and medical history including thyroid disease, diabetes, hypertension, and tuberculosis. Moreover, patients were asked about their experiences in acupuncturing, tattooing (including eyebrow tattooing), piercing (including piercing for earrings), intravenous drug use, intranasal drug use, blood transfusions, digestive endoscopy, dental procedures, surgery, and dialysis procedures, diagnosis of hemophilia, a familial history of hepatobiliary disease and the number of sexual partners.

Categorical variables were compared with Fisher's exact test or the chi-square test, and continuous variables were compared with the independent t-test or nonparametric Mann-Whitney U-test. A logistic regression analysis was performed to examine factors related to HCV infection. Considering behavioral differences by gender, we performed a multivariate logistic regression separately for males and females. STATA version 11 was used for all statistical analyses (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

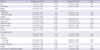

In total, 917 patients were enrolled, including 711 patients in the HCV group (77.5%) and 206 in the comparison group (22.5%) (Table 1). The mean age of the patients in the HCV group was 58.1 yr, and half of them were male (49.9%), while the comparison group included younger patients (53.3 yr old), with a larger number of males (64.6%), compared to that in the HCV group. These differences were statistically significant.

Seventy-seven patients (10.9%) had hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), 118 patients (16.6%) had liver cirrhosis (LC), and 514 patients (72.5%) had chronic hepatitis in the HCV group, whereas the comparison group included 65 patients (12.2%) with HCC, 67 patients (32.6%) with LC, and 63 patients (36.6%) with chronic hepatitis, which were not caused by either HCV or HBV. About 25% of patients in the comparison group had various other hepatobiliary diseases, including hepatic hemangioma, benign hepatic cysts, pancreatitis, and biliary stone diseases.

A total of 52.2% of patients in the HCV group was current or former drinkers, and 49.4% were current or former smokers. Compared to the HCV group, the proportions of alcohol drinkers and cigarette smokers were higher in the comparison group, because it included patients with alcoholic liver disease (P < 0.01). Patients in the HCV group showed a significantly higher rate of needle stick injuries, dental procedures, tattooing, piercings, intravenous drug use, remote transfusions more than 20 yr ago, and surgery. Acupuncture history was popular in both the HCV group (82.0%) and the comparison group (74.8%), which was not statistically significant (Table 1).

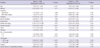

A univariate analysis showed that age, gender, history of acupuncture, tattooing, piercing, intravenous drug use, needle stick injury, transfusions received more than 20 yr ago, dental procedures, surgery, and multiple sexual partners (≥ 4) were significantly associated with HCV infection, whereas family history of hepatobiliary disease was not associated with HCV infection (Table 2).

In the multivariate logistic regression, we excluded smoking status, marital status, and piercing, because smoking status was highly correlated with alcohol drinking status (Spearman's correlation coefficient, 0.57; P < 0.001), marital status was highly correlated with age (Spearman's correlation coefficient, 0.45; P < 0.001), and piercing was significantly correlated with tattooing by Spearman's correlation analysis (Spearman's correlation coefficient, 0.44; P < 0.001). The multivariate logistic analysis showed that chronic HCV infection was significantly associated with age (odds ratio [OR], 1.03; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.01-1.05), needle stick injury (OR, 4.72; 95% CI, 1.02-21.73), tattooing (OR, 2.07; 95% CI, 1.13-3.78), and dental procedures (OR, 2.96; 95% CI, 1.35-6.48). The average number of sexual partners was also associated with HCV infection. People who had 2-3 partners and > 4 partners were about 2 times and 4 times more likely to have an HCV infection compared to people who had one sexual partner, respectively. In addition, we found that having a blood transfusion more than 20 yr ago (OR, 2.99; 95% CI, 1.20-7.41) and having undergone any surgical procedure were positively associated with HCV infection (OR, 1.89; 95% CI, 1.17-3.06). However, family history of hepatobiliary disease was not associated with HCV infection (Table 2).

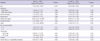

The results of a univariate subgroup analysis according to gender are summarized in Table 3. We present adjusted ORs for males and females in Table 4. In males, age (OR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.02-1.07), needle stick injury (OR, 13.83; 95% CI, 1.55-122.65), tattooing (OR, 7.31; 95% CI, 1.46-36.62), and multiple sexual partners (≥ 4) (OR, 3.90; 95% CI, 1.81-8.43) were significantly associated with HCV infection, whereas having a transfusion more than 20 yr ago was not (OR, 7.80; 95% CI, 0.95-63.79). In females, acupuncture (OR, 3.24; 95% CI, 1.42-7.40), transfusion more than 20 yr ago (OR, 2.99; 95% CI, 1.02-8.78), and surgery (OR, 2.07; 95% CI, 1.03-4.18) were significantly associated with chronic HCV infection.

In this multicenter case-control study, we found that needle stick injury, dental procedure, tattoo, surgery, multiple sex partners, and blood transfusion more than 20 yr ago were significantly associated with chronic HCV infection in Korea. Factors for chronic HCV infection differed between male and female patients.

In our data, prevalence of HCV infection increased with age, peaking at over 60 yr. This age pattern is similar to prevalence data reported in Japan, China, Turkey, Spain, and Italy, but different from those in the United States, Australia, and northern Europe, where the peak prevalence was observed in subjects aged 30-49 yr (2, 18), suggesting that there may be different risk factors associated with HCV infection according to different geographic areas. Previous studies of HCV epidemiology in Korea reported that transfusion before 1992 was a strong factor for transmission (13, 14); however, findings with regard to other risk factors, such as injection drug use, needle stick injury, surgery, and tattooing have been limited (15-17). Moreover, those studies were performed more than 10 yr ago and were community-based whereas this one was a hospital-based.

Injection drug use (IDU) is one of the most important risk factors for HCV infection in many countries, especially among young adults (1). However, our study participants were relatively old and IDU has not been common in Korea. In our study, all 26 patients with a history of IDU were in the HCV group, and there was no IDU in the NBNC group (P = 0.004). Clearly, injection drug users in our study were more likely to have HCV infection; however, further investigation is necessary, as the rate of IDU is relatively low.

Whether acupuncture is a risk factor for HCV infection remains in dispute (7, 14, 19-21). In our study, the prevalence of acupuncture was high in both groups (HCV group; 82.1%, NBNC group; 74.8%), and was not associated with overall HCV infection (P = 0.09). However, in subgroup analysis, acupuncture was a risk factor for HCV infection among women, while it was not among men. This result was compatible with results of a previous study, which reported that the attributable risk fraction of acupuncture was 9% for men, and 55% for women (total 38%) among older adults (≥ 40 yr old) in Korea (17). Patterns of acupuncture may differ according to gender; however, it has not been evaluated in detail in this study.

Tattooing as a risk factor for HCV infection has also been controversial (5, 7, 13, 16, 22). In this study, people who had tattoos were about 2 times more likely to have HCV infection, compared to people who did not. However, in subgroup analysis, tattoo was an independent factor for HCV infection in men only, not in women, and men who had tattoos were 7 times more likely to have HCV infection, compared to those who did not. In this study, tattooing included eyebrow tattooing which was common in middle aged women for cosmetic purposes in Korea. Details on tattooing methods and tattooing areas were not examined in the study, but might be worthy of investigation in future studies.

The occupational exposure of HCV transmission occurs often in health care workers and individuals at risk (e.g., military settings, incarcerated in prison or jail, and end-stage renal disease) mostly via HCV-contaminated needle stick injuries (23, 24). In our study, needle stick injury was a strong independent risk factor for HCV infection (OR, 11.0). Further study on type of occupation (e.g., healthcare worker) or details on conditions at exposure is required. Nosocomial transmission is a well established route of HCV infection. A study in Italy showed that HCV transmission in a surgical setting was identified by administration of propofol in multi-dose vials (25). Findings from another study suggested that HCV transmission to five patients during open heart surgery occurred through an HCV-infected cardiac surgeon (26). However, surgical procedures as a risk factor for HCV infection are controversial in Korea (13, 15, 16). A community-based survey in Italy showed that dental procedures and use of glass syringes are associated with 2.5-fold and 1.9-fold increased risk for HCV infection (27), respectively, whereas other studies did not show a significant association (4, 5, 14, 16, 19). Our multivariate analysis showed that dental procedures and surgical procedures were significantly associated with HCV infection in Korea, whereas digestive endoscopy was not. A comprehensive review revealed only 35 cases of transmission via digestive endoscopic procedures in the prior decade, and the estimated HCV infection rate was 1 per ten million procedures (28, 29). Therefore, our data suggest that standard precautions in dental and surgical procedure should be improved in Korea.

HCV screening of blood donors began in Korea in 1992 (15), and transfusion was no longer a risk factor for HCV infection. Similarly, in our study, having a blood transfusion more than 20 yr ago was a significant risk factor for HCV infection, compared to having it within 20 yr. This finding is compatible with results of other studies in Korea (13) .

Sexual transmission of HCV occurs uncommonly, except among men having sex with men (1, 30, 31). A 10-yr prospective follow-up study found that the risk of HCV sexual transmission with monogamous couples was extremely rare (30). However, multiple sexual partners and early age (< 18 yr old) at the first sexual intercourse were independent predictors of anti-HCV positivity in a study conducted in the United States (32). According to our data, having multiple sexual partners (P = 0.002) and early age (< 18 yr old) at first sexual intercourse (13 of 379 in the HCV group vs 0 of 143 in the comparison group; P = 0.02, data not shown) were significantly associated with chronic HCV infection, which is consistent with findings from a US study (32).

Results have been controversial on intra-familial transmission of HCV. The prevalence of anti-HCV positivity among familial members living with patients with HCV ranges widely (from 0% to 27%) (1). Some studies have reported that anti-HCV positivity is highly correlated with duration of marriage and actual exposure (e.g., more frequent sexual contact and shared toothbrushes) (33, 34). In contrast, a study in Italy showed that among 1,379 household contacts of 585 HCV antibody-positive subjects, the prevalence of anti-HCV among household contacts was 7.3% (15.6% in spouses and 3.2% in other relatives), and the type of relationship (spouses vs other relatives), rather than years of marriage (≤ 20 yr vs > 20 yr) was an independent predictor of anti-HCV positivity among household contacts (35). In the current study, familial contact with an HCV positive patient was not a significant risk factor for HCV infection (P = 0.327, data not shown). This result may be related to the nature of the patients in our control group, who were mostly diagnosed with alcoholic liver disease, hemangioma, or hepatic cysts, which are associated with genetic factors.

This study had several limitations. First, for the comparison group patients we recruited patients who visited the same hospitals because of the chronic liver diseases caused by other than hepatitis B or C, so that they were not a community-based or liver disease-free control population. However, a survey of patients with liver diseases in the same clinic may have reduced recall bias during the questionnaire survey. Second, a significant difference in sample size was observed between the HCV group and the comparison groups. The reason was that the questionnaire survey was time consuming, and many patients with liver disease not related to HCV did not agree to participate in this study. Third, some patients did not want to answer private questions, such as those pertaining to sexual relationships, which resulted in missing data. The fundamental limitation was that a previous exposure history to the risk factors does not indicate a cause of HCV infection.

In conclusion, this study showed that the major risk factors for chronic HCV infection are closely related to conventional or alterative healthcare procedures and multiple sexual partners in Korea where intravenous drug use is uncommon. Therefore, standard precautions during invasive procedures in the healthcare setting and reinforced public education on risky behaviors are required to prevent HCV infection.

Figures and Tables

Table 1

Characteristics of the study populations with chronic liver disease

*Alcoholic cirrhosis (n = 50), cryptogenic cirrhosis or other causes (n = 17); †alcoholic liver disease (n = 2), non alcoholic fatty liver disease (n = 44), autoimmune hepatitis (n = 11), primary biliary cirrhosis (n = 4); ‡pancreatitis (n = 7), hepatic hemangioma (n = 7), biliary stone diseases or cholangitis (n = 11), liver abscess (n = 6), hepatic cyst (n = 5) and others (n = 11). S.D., standard deviation; HCV, hepatitis C virus; Comparison group, liver disease without hepatitis B or hepatitis C infection.

Table 2

Factors associated with chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection: Results of univariate and multivariate analysis

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the research coordinators (Won Hee Jeong, Ogee Kang, and Eun Gyeong Oh) for their devotion to this study.

References

1. Memon MI, Memon MA. Hepatitis C: an epidemiological review. J Viral Hepat. 2002. 9:84–100.

2. Alter MJ. Epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2007. 13:2436–2441.

3. Esteban JI, Sauleda S, Quer J. The changing epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection in Europe. J Hepatol. 2008. 48:148–162.

4. Karmochkine M, Carrat F, Dos Santos O, Cacoub P, Raguin G. A case-control study of risk factors for hepatitis C infection in patients with unexplained routes of infection. J Viral Hepat. 2006. 13:775–782.

5. Delarocque-Astagneau E, Pillonel J, De Valk H, Perra A, Laperche S, Desenclos JC. An incident case-control study of modes of hepatitis C virus transmission in France. Ann Epidemiol. 2007. 17:755–762.

6. Ali SA, Donahue RM, Qureshi H, Vermund SH. Hepatitis B and hepatitis C in Pakistan: prevalence and risk factors. Int J Infect Dis. 2009. 13:9–19.

7. Sun CA, Chen HC, Lu CF, You SL, Mau YC, Ho MS, Lin SH, Chen CJ. Transmission of hepatitis C virus in Taiwan: prevalence and risk factors based on a nationwide survey. J Med Virol. 1999. 59:290–296.

8. Chung H, Ueda T, Kudo M. Changing trends in hepatitis C infection over the past 50 years in Japan. Intervirology. 2010. 53:39–43.

9. McCaughan GW, Omata M, Amarapurkar D, Bowden S, Chow WC, Chutaputti A, Dore G, Gane E, Guan R, Hamid SS, et al. Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver consensus statements on the diagnosis, management and treatment of hepatitis C virus infection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007. 22:615–633.

10. Suh DJ, Jeong SH. Current status of hepatitis C virus infection in Korea. Intervirology. 2006. 49:70–75.

11. Lee HS, Han CJ, Kim CY. Predominant etiologic association of hepatitis C virus with hepatocellular carcinoma compared with hepatitis B virus in elderly patients in a hepatitis B-endemic area. Cancer. 1993. 72:2564–2567.

12. Lee MS, Kim DH, Kim H, Lee HS, Kim CY, Park TS, Yoo KY, Park BJ, Ahn YO. Hepatitis B vaccination and reduced risk of primary liver cancer among male adults: a cohort study in Korea. Int J Epidemiol. 1998. 27:316–319.

13. Shin HR. Epidemiology of hepatitis C virus in Korea. Intervirology. 2006. 49:18–22.

14. Kim YS, Ahn YO, Lee HS. Risk factors for hepatitis C virus infection among Koreans according to the hepatitis C virus genotype. J Korean Med Sci. 2002. 17:187–192.

15. Shin HR, Kim JY, Ohno T, Cao K, Mizokami M, Risch H, Kim SR. Prevalence and risk factors of hepatitis C virus infection among Koreans in rural area of Korea. Hepatol Res. 2000. 17:185–196.

16. Kim YS, Ahn YO, Kim DW. A case-control study on the risk factors of hepatitis C virus infection among Koreans. J Korean Med Sci. 1996. 11:38–43.

17. Shin HR, Kim JY, Kim JI, Lee DH, Yoo KY, Lee DS, Franceschi S. Hepatitis B and C virus prevalence in a rural area of South Korea: the role of acupuncture. Br J Cancer. 2002. 87:314–318.

18. Kwon JH, Bae SH. Current status and clinical course of hepatitis C virus in Korea. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2008. 51:360–367.

19. Becheur H, Harzic M, Colardelle P, Deny P, Coste T, Dubeaux B, Chochon M, Roussin-Bretagne S, Doll J, Andrieu J. Hepatitis C virus contamination of endoscopes and biopsy forceps. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2000. 24:906–910.

20. Habib M, Mohamed MK, Abdel-Aziz F, Magder LS, Abdel-Hamid M, Gamil F, Madkour S, Mikhail NN, Anwar W, Strickland GT, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection in a community in the Nile Delta: risk factors for seropositivity. Hepatology. 2001. 33:248–253.

21. Alter MJ. Hepatitis C virus infection in the United States. J Hepatol. 1999. 31:Suppl 1. 88–91.

22. Hellard ME, Hocking JS, Crofts N. The prevalence and the risk behaviours associated with the transmission of hepatitis C virus in Australian correctional facilities. Epidemiol Infect. 2004. 132:409–415.

23. Yazdanpanah Y, De Carli G, Migueres B, Lot F, Campins M, Colombo C, Thomas T, Deuffic-Burban S, Prevot MH, Domart M, et al. Risk factors for hepatitis C virus transmission to health care workers after occupational exposure: a European case-control study. Clin Infect Dis. 2005. 41:1423–1430.

24. Rustgi VK. The epidemiology of hepatitis C infection in the United States. J Gastroenterol. 2007. 42:513–521.

25. Massari M, Petrosillo N, Ippolito G, Solforosi L, Bonazzi L, Clementi M, Manzin A. Transmission of hepatitis C virus in a gynecological surgery setting. J Clin Microbiol. 2001. 39:2860–2863.

26. Esteban JI, Gomez J, Martell M, Cabot B, Quer J, Camps J, Gonzalez A, Otero T, Moya A, Esteban R, et al. Transmission of hepatitis C virus by a cardiac surgeon. N Engl J Med. 1996. 334:555–560.

27. Guadagnino V, Stroffolini T, Rapicetta M, Costantino A, Kondili LA, Menniti-Ippolito F, Caroleo B, Costa C, Griffo G, Loiacono L, et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and genotype distribution of hepatitis C virus infection in the general population: a community-based survey in southern Italy. Hepatology. 1997. 26:1006–1011.

28. Nelson DB. Infectious disease complications of GI endoscopy: part II, exogenous infections. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003. 57:695–711.

29. Wu H, Shen B. Health care-associated transmission of hepatitis B and C viruses in endoscopy units. Clin Liver Dis. 2010. 14:61–68. viii

30. Vandelli C, Renzo F, Romano L, Tisminetzky S, De Palma M, Stroffolini T, Ventura E, Zanetti A. Lack of evidence of sexual transmission of hepatitis C among monogamous couples: results of a 10-year prospective follow-up study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004. 99:855–859.

31. Thomas DL, Zenilman JM, Alter HJ, Shih JW, Galai N, Carella AV, Quinn TC. Sexual transmission of hepatitis C virus among patients attending sexually transmitted diseases clinics in Baltimore--an analysis of 309 sex partnerships. J Infect Dis. 1995. 171:768–775.

32. Alter MJ, Kruszon-Moran D, Nainan OV, McQuillan GM, Gao F, Moyer LA, Kaslow RA, Margolis HS. The prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, 1988 through 1994. N Engl J Med. 1999. 341:556–562.

33. Guadagnino V, Stroffolini T, Foca A, Caroleo B, Loiacono L, Giancotti A, Menniti F, Piazza M. Hepatitis C virus infection in family setting. Eur J Epidemiol. 1998. 14:229–232.

34. Kao JH, Hwang YT, Chen PJ, Yang PM, Lai MY, Wang TH, Chen DS. Transmission of hepatitis C virus between spouses: the important role of exposure duration. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996. 91:2087–2090.

35. Caporaso N, Ascione A, Stroffolini T. Investigators of an Italian Multicenter Group. Spread of hepatitis C virus infection within families. J Viral Hepat. 1998. 5:67–72.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download