Abstract

The intrathecal drug delivery system (ITDDS), an effective treatment tool for intractable spasticity and pain, is associated with various complications but breakage of the catheter is rare. We report the case of a 50-yr-old man with ITDDS, in whom an intrathecal catheter was severed, resulting in a 28.6-cm-long intrathecal fragment. The catheter completely retracted into the intrathecal space from the anchor site. The catheter was severed during spine flexion, and the total distal fragment was repositioned in the intrathecal space. Although the outcome of ITDDS was associated with the length or diameter of the broken catheter, no neurologic complications occurred in our patient. Thus, we inserted another catheter instead of removing the old one. Thereafter, the patient has been regularly followed up, and no neurologic complications have developed during the 28 months.

The intrathecal drug delivery system (ITDDS) is known to be an effective tool for the treatment of spasticity, chronic intractable pain, and cancer pain (1-3). Since this system allows delivery of drugs directly to the central nervous system (4), it has the advantage of decreasing systemic side effects by reducing the dose required (1, 2, 5-8).

Several reports have described the mechanical complications of ITDDS (4, 6-10). Although catheter-related problems are infrequent (11-18), catheter complications such as kinks, breaks, or disconnections are common causes of reoperation (2, 19) or pump failure (13). The recent increase in the use of intrathecal pump implantation may lead to an increased incidence of such complications; therefore, guidelines are needed to prevent or resolve these complications.

Here, we introduce our protocol and describe the experience with a broken catheter, where the entire distal fragment, approximately 28.6 cm in length, remained in the intrathecal space.

A 50-yr-old man with right upper extremity pain caused by brachial plexus injury after a traffic accident visited our pain clinic on 10 August 2006. His pain intensity was 9/10 cm on a visual analogue scale (VAS). His symptoms were continuing electric shock-like and burning pain, decreased sensation, and atrophied muscles.

Cervical epidural block, Bier block, root block, pulsed radio-frequency treatment and ketamine and lidocaine infusion therapy had been ineffective. Despite oral medications, including opioids (containing morphine 120 mg/day), an anticonvulsant, and an antidepressant, the pain intensity remained above 6 on the VAS. In addition, severe breakthrough pain led him to visit the emergency department 2-3 times every week, where he would receive 30-40 mg of intravenous morphine. We thus decided to implant an ITDDS (SynbchroMed®II Infusion System; Medtronic Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA).

For implantation, the 16-gauge spinal needle was introduced at the L3/4 intervertebral space, with a paramedian approach. After confirmation of CSF free flow, the intrathecal catheter was passed through the needle, and the distal tip was located at the T8 vertebral level. Next, we fixed the catheter using a 90° angle anchor to the fascia by suturing the suture holes and notched ends.

The starting dose of intrathecal morphine was 0.25 mg/day, and the dosage was increased by approximately 50% step-by-step over 2 days. The pain intensity dramatically decreased, to 2 on the VAS, with a morphine dose of 0.5 mg/day.

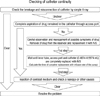

One month later, the patient complained that symptoms were suddenly aggravated, with a pain intensity of 6 on the VAS, without any neurologic symptoms. Despite increasing the flow rate to 1 mg/day, the pain intensity did not decrease. He described a one-time sudden electric shock-like pain through his lower extremities while moving to pick something up. Therefore, we followed our protocol to check the catheter continuity (Fig. 1).

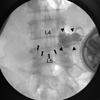

Continuity of the catheter could not be clearly identified on simple radiologic evaluation; therefore, we decided to perform a dye study using contrast media under C-arm fluoroscopy. Since overdose complications may develop due to accidental infusion of remaining drug from the catheter into the intrathecal space, the catheter needed to be aspirated via the access port before administration of contrast media; no fluid was aspirated from the access port.

During the dye study, we found that the catheter was broken, as the contrast media spread around the anchor (Fig. 2). In addition, the entire distal part of the broken catheter had been dislodged from the anchor into the intrathecal space and was looped at the L4/5 vertebral level (Fig. 2). To remove the distal part of the broken catheter, invasive surgery was required. However, there was no CSF leakage or catheter-related complications; therefore, after explaining the possible future complications such as infection, pain, nerve compression, or migration of the catheter remains intrathecally, informed consent was obtained to insert a new catheter and leave the broken catheter in place.

During the exploration, we verified that the catheter and anchor were broken (Fig. 3). Since the secured catheter measured 60.4 cm in length, the length of the catheter remnant was determined to be 28.6 cm (total length = 89 cm).

After removal of the proximal catheter and anchor, a new catheter was inserted into the intrathecal space and was connected at the pump. The patient's pain decreased to 2 on the VAS. He was discharged with instructions to be aware of possible neurologic complications such as lower extremity weakness. No neurological complications were observed during the 28-month follow-up period.

To our knowledge, this is the first report of a 28.6-cm-long distal fragment of a broken catheter completely repositioning into the intrathecal space. Despite previous findings of a relationship between the outcome and length or diameter of the fragment of the broken catheter (17), we chose regular observation instead of removing the catheter, because the patient had no neurologic symptoms (14-17).

In cases of abrupt changes in pain intensity in a patient who has an ITDDS, mechanical errors, including those associated with the pump or catheter, should be considered first. Pump failures such as drug or battery depletion, a programming error, and motor dysfunction are detectable easily using a drug refill test. However, for checking for catheter-related problems, step-by-step access is required because of the long pathway of the catheter (Fig. 1).

Before administration of contrast agent during the dye study, removal of drugs in the catheter is essential to prevent an overdose. If aspiration is not completely achieved, drugs in the pump reservoir should be replaced with preservative-free saline, and the procedure should be suspended until the anticipated time that the drug will be replaced with the saline (Fig. 1).

In the present case, we assumed 2 probable causes of catheter breakage. One was that the patient performed normal activities and had a normal range of motion, except for the right upper extremity. His level of activity was high compared with that of patients with spasticity or malignant cancer, especially during spine movement. Thus, it appeared that the catheter may have been damaged by repetitive movement of the spine. The patient's history suggested that the catheter broke during spine flexion, and the total distal fragment was repositioned into the intrathecal space. It is possible that the distal fragment bumped against the cord or cauda equina, such as that occurring in whiplash, during the movement. Such a one-time event may cause electric shock-like pain.

The other possible causes are a tight knot and the fixation of the locking channel of the anchor to the fascia. During the exploration, we found that the locking channel of the anchor was broken at the same place as the catheter breakage; we also observed a separated knot, which was sutured to the fascia. The tight knot may have pressed onto the anchor and catheter. The knot that was fixed to the fascia may have been tightened by the same event that resulted in the shearing force during flexion, which may have made the knot tighter with elongation of the back muscles. The pressure of the tight suture and repetitive flexion activities may have damaged the anchor and catheter.

It is impossible to rule out any pre-existing hidden defect of the anchor or one that may have been introduced during suturing. However, if any defect existed coincidentally, we could assume that the patient's pain was not correlated with the sudden neurologic symptoms that occurred due to a strong traction force, and the broken remnant would have remained in the original position of the catheter pathway.

The difference between a broken ITDDS catheter and that with other catheter systems (epidural catheter, catheter for CSF drain, etc.) is the risk of drug overdose. In the intrathecal space, a small dose of morphine can directly influence the central nervous system. Moreover, morphine is water soluble and can spread easily in the CSF; therefore, an abrupt tear and insertion of the catheter into the intrathecal space in ITDDS can cause a drug overdose. If the distal fragment is long, as it was in the present case, and suddenly enters the intrathecal area, the possibility of drug overdose may be greatly increased. Fortunately, this patient showed no complications, because of the relatively low daily drug dose. Further, the drug in the distal broken catheter may have contributed to the continuous analgesic effect experienced for several days after the event.

To remove an intrathecal foreign body, invasive surgery (such as laminectomy or laminotomy and incision of the dura) is necessary. Therefore, the risks and benefits should be assessed before decision making in such cases. If there are no symptoms and complications, the removal of the fragmented catheter may not be required, but regular observation is necessary (17).

In conclusion, if withdrawal symptoms or sudden severe pain appears in a patient with an ITDDS, mechanical failure, including that associated with the catheter, should be examined in a step-by-step process. The patient should be informed about the possibility of catheter breakage, especially with normal spine movement. To prevent the catheter breakage, practitioners should take great care to ensure that the catheter is firmly anchored without being excessively tight.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Belverud S, Mogilner A, Schulder M. Intrathecal pumps. Neurotherapeutics. 2008. 5:114–122.

2. Cohen SP, Dragovich A. Intrathecal analgesia. Anesthesiol Clin. 2007. 25:863–882. viii

3. Jones RL, Rawlins PK. The diagnosis of intrathecal infusion pump system failure. Pain Physician. 2005. 8:291–296.

4. Ruan X. Drug-related side effects of long-term intrathecal morphine therapy. Pain Physician. 2007. 10:357–366.

5. Williams BS, Christo PJ. Obstructed catheter connection pin discovered during intrathecal baclofen pump exchange. Clin J Pain. 2009. 25:256–259.

6. Fluckiger B, Knecht H, Grossmann S, Felleiter P. Device-related complications of long-term intrathecal drug therapy via implanted pumps. Spinal Cord. 2008. 46:639–643.

7. Miele VJ, Price KO, Bloomfield S, Hogg J, Bailes JE. A review of intrathecal morphine therapy related granulomas. Eur J Pain. 2006. 10:251–261.

8. Li TC, Chen MH, Huang JS, Chan JY, Liu YK. Catheter migration after implantation of an intrathecal baclofen infusion pump for severe spasticity: a case report. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2008. 24:492–497.

9. Ko WM, Ferrante FM. New onset lumbar radicular pain after implantation of an intrathecal drug delivery system: imaging catheter migration. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2006. 31:363–367.

10. Motta F, Buonaguro V, Stignani C. The use of intrathecal baclofen pump implants in children and adolescents: safety and complications in 200 consecutive cases. J Neurosurg. 2007. 107:32–35.

11. Vodapally MS, Thimineur MA, Mastroianni PP. Tension pseudomeningocele associated with retained intrathecal catheter: a case report with a review of literature. Pain Physician. 2008. 11:355–362.

12. Follett KA, Naumann CP. A prospective study of catheter-related complications of intrathecal drug delivery systems. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000. 19:209–215.

13. Knight KH, Brand FM, McHaourab AS, Veneziano G. Implantable intrathecal pumps for chronic pain: highlights and updates. Croat Med J. 2007. 48:22–34.

14. Ugboma S, Au-Truong X, Kranzler LI, Rifai SH, Joseph NJ, Salem MR. The breaking of an intrathecally-placed epidural catheter during extraction. Anesth Analg. 2002. 95:1087–1089. table of contents.

15. Olivar H, Bramhall JS, Rozet I, Vavilala MS, Souter MJ, Lee LA, Lam AM. Subarachnoid lumbar drains: a case series of fractured catheters and a near miss. Can J Anaesth. 2007. 54:829–834.

16. Simmerman SR, Fahy BG. Retained fragment of a lumbar subarachnoid drain. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 1997. 9:159–161.

17. Forsythe A, Gupta A, Cohen SP. Retained intrathecal catheter fragment after spinal drain insertion. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2009. 34:375–378.

18. Hurley RJ, Lambert DH. Continuous spinal anesthesia with a microcatheter technique: preliminary experience. Anesth Analg. 1990. 70:97–102.

19. Vender JR, Hester S, Waller JL, Rekito A, Lee MR. Identification and management of intrathecal baclofen pump complications: a comparison of pediatric and adult patients. J Neurosurg. 2006. 104:9–15.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download