Abstract

Plastic bronchitis is an uncommon disorder characterized by the formation of bronchial casts. It is associated with congenital heart disease or pulmonary disease. In children with underlying conditions such as allergy or asthma, influenza can cause severe plastic bronchitis resulting in respiratory failure. A review of the literature showed nine cases of plastic bronchitis with H1N1 including this case. We report a case of a child with recurrent plastic bronchitis with eosinophilic cast associated with influenza B infection, who had recovered from plastic bronchitis associated with an influenza A (H1N1) virus infection 5 months previously. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of recurrent plastic bronchitis related to influenza viral infection. If patients with influenza virus infection manifest acute respiratory distress with total lung atelectasis, clinicians should consider plastic bronchitis and early bronchoscopy should be intervened. In addition, management for underlying disease may prevent from recurrence of plastic bronchitis.

Plastic bronchitis is a rare disease characterized by recurrent formation of bronchial casts (1). Plastic bronchitis can be associated with inflammatory diseases of the lungs such as asthma and pulmonary infection (1). Influenza is one of major etiologic agents of acute viral lower respiratory tract infections in hospitalized children (2). Although the latest H1N1 (here after referred to as H1N1) epidemic was declared over by the World Health Organization on August 10, 2010, the WHO has cautioned that H1N1 may circulate as a seasonal influenza for years (3). During the H1N1 pandemic, a higher incidence and mortality due to H1N1 infection was evident among children compared with seasonal influenza, and pneumonia was the most common complication of H1N1 infection (4, 5). In children with pneumonia accompanied by influenza viral infection, severe plastic bronchitis can occur. We report a child with recurrent plastic bronchitis associated with H1N1 and influenza B virus.

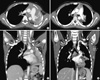

A 7-yr-old boy was admitted to a local hospital because of a 1-day history of cough, fever and aggravating dyspnea on November 15, 2009. Real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) for H1N1 was positive, and the patient was treated with oral oseltamivir. On physical examination, breath sounds were decreased in the left lung. A chest radiograph revealed complete atelectasis in the left lung and over-inflation of the right lung (Fig. 1A). A chest computed tomography (CT) scan showed left main bronchial obstruction with low attenuated materials and atelectasis of the left lung (Fig. 2A, C). Laboratory studies revealed as hemoglobin of 13.2 g/dL, white blood cell count of 10,600/µL (polymorphonuclear cells, 95.8%; lymphocytes, 1.5%; and eosinophils, 2.7%), and platelet count of 318,000/µL. The C-reactive protein level was 2.3 mg/dL, erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 6 mm/hr, and antistreptolysin O titer was 105 IU/mL. Anti-mycoplasma antibody was negative. Total IgE exceeded 3,000 IU/mL. Electrolytes, and liver and kidney function tests were in the normal range. The arterial blood gas analysis was as follows: pH 7.42, pCO2 34.5 mmHg, pO2 67.5 mmHg, and HCO3 22.3 mmHg. Gram-stain, acid fast stain, potassium hydroxide mounts, Mycobacterium tuberculosis culture, culture for other sputum bacteria, and fungus culture of sputum were negative. After supplying O2 via an oxygen mask, dyspnea was relieved and aeration of the left lung on the chest radiograph was also improved. The patient received mucolytics, chest physiotherapy, and antibiotics. Although amoxicillin-clavulanate was chosen due to the patient's history of allergy to ceftriaxone, an urticarial rash developed after amoxicillin-clavulanate administration. The rash subsided with antihistamine use. On day 4 following admission, the patient underwent a bronchoscopy because of aggravating dyspnea. The bronchoscopy showed total obstruction of the left main bronchus by a rubbery cast. The chest radiograph and CT scan after extraction of the cast showed the left lung recovered with good aeration (Fig. 2B, D). The patient was discharged 12 days after admission.

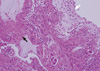

The same patient was referred to the emergency department of our hospital because of acute respiratory distress 5 months later after the first attack. The patient was hospitalized at a local hospital 2 days before because of a 4-day history of cough and mild fever. The patient was managed with antibiotics and mucolytics under the diagnosis of pneumonia. However, shortness of breath was aggravated suddenly and a chest radiograph showed total atelectasis of the left lung (Fig. 1B). On arrival at our emergency room, the patient presented with tachypnea, deceased breath sounds in the left lung field, and chest retraction. SpO2 was 85% on 100% face mask oxygen, and the arterial blood gas analysis was as follows: pH 7.33, pCO2 37.9 mmHg; pO2 68.8 mmHg, and HCO3, 19.5 mmHg. The body temperature was 36.7℃, pulse rate was 164/min, respiratory rate was 48/min, and blood pressure was 100/60 mmHg. The patient was intubated and mechanical ventilation was applied in the emergency room due to respiratory failure. Laboratory studies revealed hemoglobin of 14.4 g/dL, white blood cell count of 23,200/µL (polymorphonuclear cells, 95.4%; lymphocytes, 2.0%; and eosinophils, 0.4%), and platelet count of 357,000/µL. The C-reactive protein level was 5.2 mg/dL, erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 11 mm/hr, lactate dehydrogenase was 941 U/L, and antistreptolysin O titer was 85 IU/mL. Urine pneumococcal antigen and the anti-mycoplasma antibody were negative. The rapid nasal swab influenza antigen test was negative for influenza A but positive for influenza B virus. RT-PCR for H1N1 and influenza B virus were negative and positive, respectively. Shell vial culture for influenza A, parainfluenza, adenovirus, and respiratory syncytial virus were all negative, but only for influenza B was positive. To exclude allergic bronchial fungal disease, we also did tests for fungal infection. Each fungus culture with specimens obtained from endotracheal aspiration and bronchial lavage was negative. Aspergillus antigen and antibody immunoglobulin G were negative. Electrolytes, liver and renal function tests were within normal range. A chest CT scan demonstrated low attenuated materials filling the left main and lobar bronchi, and total consolidation or atelectasis in the left lung. An electrocardiogram and echocardiography were normal. On the admission day, an emergent bronchoscopy was performed and thick rubbery material was extracted out from the left main bronchus. The patient received a 5-day course of oral oseltamivir and intravenous methylprednisolone for 5 days. Antibiotics (cefotaxime, netilmycin, clindamycin,and roxithromycin) and oral leukotriene modulator were administered. Massive chest physiotherapy with inhaled corticosteroids, bronchodilator, and mucolytics was carried out. In spite of the bronchoscopic removal and medical treatment, the patient experienced respiratory distress again on day 2 of hospitalization. Flexible bronchoscopy at the bedside in the intensive care unit revealed a gelatinous yellow plug in the left bronchus. Thus, a second bronchoscopic removal of bronchial casts was performed on day 3 of hospitalization (Fig. 3). After removal of the cast, dyspnea resolved and chest radiography revealed a marked improvement. On histologic examination, the firm and rubbery cast was composed of fibrinous clot with eosinophil-dominant inflammatory exudates (Fig. 4). There were no Charcot-Leyden crystals, which are frequently seen in sputum from patients with bronchial asthma. The patient was extubated on day 4 of hospitalization and discharged after 2 weeks without any complications. The patient also underwent allergic evaluations. Total IgE was 3,560 IU/mL. Some specific IgE reactions using UniCAP® (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) were positive: Dermatophagoides pteronyssi of 3.01 k/U, D. farinae of 15.9 kU/L, and Alternaria tenuis of 29.6 k/U. Unicap of cat fur, ragweed, mugwort, and Aspergillus fumigatus were negative. Eosinophil cationic protein was 12.1 ng/mL. After tachypnea was improved, spirometry was performed. The forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), forced vital capacity (FVC), and FEV1/FVC ratio, were 1.19 L, 1.20 L, and 0.99 respectively. The forced expiratory flow 25%-75% was 1.38 L/s. The serial spirometry was within normal limit on follow-up visits after discharge. A methacholine provocation test was performed 3 months later after discharge in our out-patient clinic. The provocative concentration that resulted in a 20% fall in FEV1 was 8.0 mg/mL, which means bronchial hyperresponsiveness. Therefore, we recommended that the patient use inhaled corticosteroids for 3 months and get vaccinated for H1N1 and seasonal influenzas during influenza season. The patient has been in a good condition without respiratory infection, asthma attack, and recurrence of plastic bronchitis for 12 months since discharge.

Most patients with H1N1 were self-limited and recovered without complications. However, it can complicate severe lower respiratory illness including plastic bronchitis in young age groups (4, 5). Plastic bronchitis might occur more frequently in children than in adults associated with H1N1 infection (6, 7).

We reviewed nine cases, including the present case, of plastic bronchitis associated with H1N1 in the English literature (Table 1) (8-11). The median age was 5 yr (range 2-7 yr) with a predominance of boys (89%). Interestingly, all nine cases were Asian, Japanese, Chinese, or Korean. Cough and fever were most common initial symptoms. The left lung was more frequently involved (6/9 cases, 67%) than the right lung (3/9 cases, 33%). The most common radiographic finding was atelectasis of the affected lung (8/9 cases, 89%). They were children with allergy (2/9 cases, 22%), asthma (2/9 cases, 22%), and no underlying disease, but with a wheeze on common cold (2/9 cases, 22%). The remainder were previously healthy (3/9 cases, 34%). All the patients underwent bronchoscopic removal of casts. Histology of the casts showed mostly inflammatory cells (7/8 cases, 88%) and mucinous substance with no inflammatory cells (1/8 case, 12%). Good prognosis was shown as complete recovery (7/9 cases, 78%) and recovery following inhaled β agonist use (1/9 case, 11%). Only this present case had recurrent plastic bronchitis with influenza B virus infection 5 months later after recovery from plastic bronchitis with H1N1.

Although plastic bronchitis can occur in previously healthy children, pediatric patients with allergy or asthma are at high risk of plastic bronchitis (12). Our patient had no history of atopy such as atopic dermatitis, allergic rhinitis, and asthma. However, the methacholine provocation test revealed bronchial hyperresponsiveness. Considering the patient's known allergy to some antibiotics, high total IgE and elevated specific IgE to house dust mites, the patient seemed to have atopy. Although it is not clear whether influenza virus has a causal link for the development of asthma, pandemic H1N1 can induce severe asthma attack in atopic children who have no history of asthma. In a recent study, H1N1 caused asthma attack more than seasonal influenza did (13). Another study explained that repeated viral infections cause prolongation of airway hyperresponsiveness in atopic subjects (14). Our patient experienced two attacks of severe plastic bronchitis with H1N1 and influenza B infection. The patient was infected with influenza B 5 months later after recovery from H1N1. H1N1 might induce prolongation of bronchial hyperresponsiveness, in which a sticky inflammatory plug obstructs airways more easily and rapidly before the casts are expectorated spontaneously. Children with bronchial hyperresponsiveness may be prone to marked increase in airway resistance by inflammatory exudate. When large bronchial casts blocks the main bronchus, it acts as a stop valve and results in total lung atelectasis (15).

In plastic bronchitis with an underlying atopic condition, asthmatic and infectious conditions can prompt the use of anti-inflammatory regimens, including inhaled and oral steroids (1). In this case, we prescribed inhaled steroids to prevent recurrence of bronchial casts. According to Hasegawa et al. (13), 20 (90.9%) among 22 patients who experienced severe asthma attack during the H1N1 pandemic did not receive long-term treatment. The treatment of the underlying pulmonary disease such as asthma may decrease or prevent cast formation (13).

Plastic bronchitis in children can complicate severe hypoxic damage and lead to death. Bronchoscopic intervention should be performed as early as possible because obstruction of the major airways by bronchial casts may proceed very rapidly. In some cases, repeated bronchoscopy may be required to find bronchial casts (8). Anti-viral agents may less effective for the treatment of plastic bronchitis (8). Besides bronchoscopic removal of bronchial casts, therapeutic options include chest physiotherapy, oseltamivir, antibiotics, mucolytics, and steroids. Also, macrolides have emerged as an immunomodulator, and treatment with low-dose azithromycin in idiopathic plastic bronchitis has been successful (1).

Immunization is the most effective strategy of preventing complicated influenza infection (17). Kwon et al. (18) reported that none of children with severe neurologic complication from H1N1 in his study had been immunized for H1N1 and seasonal influenzas.

In conclusion, if patients with influenza virus infection manifest acute respiratory distress with total lung atelectasis, clinicians should consider plastic bronchitis and early bronchoscopy should be carried out. To prevent recurrence of plastic bronchitis in patients with atopy or bronchial hyperresponsiveness, inhaled corticosteroids can be used besides influenza vaccination.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Chest radiographs at the first attack with H1N1 infection in November, 2009 (A) and second attack with influenza B infection in April, 2010 (B) shows total atelectasis in the left lung and hyperaeration in the right lung. |

| Fig. 2Chest computed tomography (CT) at the first attack (A, C) reveals left main bronchial obstruction with low attenuated materials and atelectasis of the left lung. Chest CT after bronchoscopic removal of bronchial casts (B, D) shows recovered left lung with good aeration. |

| Fig. 3Casts extracted from the left main bronchus at the second attack showed preserved anatomy of the bronchial tree. |

References

1. Eberlein MH, Drummond MB, Haponik EF. Plastic bronchitis: a management challenge. Am J Med Sci. 2008. 335:163–169.

2. Neuzil KM, Mellen BG, Wright PF, Mitchel EF Jr, Griffin MR. The effect of influenza on hospitalizations, outpatient visits, and courses of antibiotics in children. N Engl J Med. 2000. 342:225–231.

3. World Health Organization. H1N1 in post-pandemic period. Accessed on 10 August 2010. Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/statements/2010/h1n1_vpc_20100810/en/index.html.

4. Hasegawa M, Okada T, Sakata H, Nakayama E, Fuchigami T, Inamo Y, Mugishima H, Tajima T, Iwata S, Morozumi M, et al. Pandemic (H1N1) 2009-associated pneumonia in children, Japan. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011. 17:279–282.

5. Kim HS, Kim JH, Shin SY, Kang YA, Lee HG, Kim JS, Lee JK, Cho B. Fatal cases of 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2011. 26:22–27.

6. Shin SY, Kim JH, Kim HS, Kang YA, Lee HG, Kim JS, Lee JK, Kim WK. Clinical characteristics of Korean pediatric patients critically ill with influenza A (H1N1) virus. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2010. 45:1014–1020.

7. Lee E, Seo JH, Kim HY, Na S, Kim SH, Kwon JW, Kim BJ, Hong SJ. Clinical characteristics and outcomes among pediatric patients hospitalized with pandemic influenza A/H1N1 2009 infection. Korean J Pediatr. 2011. 54:329–334.

8. Terano C, Miura M, Fukuzawa R, Saito Y, Arai H, Sasaki M, Ariyasu D, Hasegawa Y. Three children with plastic bronchitis associated with 2009 H1N1 influenza virus infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011. 30:80–82.

9. Deng J, Zheng Y, Li C, Ma Z, Wang H, Rubin BK. Plastic bronchitis in three children associated with 2009 influenza A (H1N1) virus infection. Chest. 2010. 138:1486–1488.

10. Hasegawa M, Inamo Y, Fuchigami T, Hashimoto K, Morozumi M, Ubukata K, Watanabe H, Takahashi T. Bronchial casts and pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus infection. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010. 16:344–346.

11. Sun DJ, Yang YS, Wang BC. Plastic bronchitis associated with severe influenza A (H1N1) in children: a case report and review of the literature. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi. 2010. 33:837–839.

12. Brogan TV, Finn LS, Pyskaty DJ Jr, Redding GJ, Ricker D, Inglis A, Gibson RL. Plastic bronchitis in children: a case series and review of the medical literature. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2002. 34:482–487.

13. Hasegawa S, Hirano R, Hashimoto K, Haneda Y, Shirabe K, Ichiyama T. Characteristics of atopic children with pandemic H1N1 influenza viral infection: pandemic H1N1 influenza reveals 'occult' asthma of childhood. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2011. 22:e119–e123.

14. Xepapadaki P, Papadopoulos NG, Bossios A, Manoussakis E, Manousakas T, Saxoni-Papageorgiou P. Duration of postviral airway hyperresponsiveness in children with asthma: effect of atopy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005. 116:299–304.

15. Bowen A, Oudjhane K, Odagiri K, Liston SL, Cumming WA, Oh KS. Plastic bronchitis: large, branching, mucoid bronchial casts in children. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1985. 144:371–375.

16. Ko JH, Kim JH, Kang JH, Kim JH, Eun BW, Kim KY, Hong JY, Oh SH. Characteristics of hospitalized children with 2009 pandemic influenza A(H1N1): a multicenter study in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2012. 27:408–415.

17. Fiore AE, Uyeki TM, Broder K, Finelli L, Euler GL, Singleton JA, Iskander JK, Wortley PM, Shay DK, Bresee JS, Cox NJ. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Prevention and control of influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010. 59:1–62.

18. Kwon S, Kim S, Cho MH, Seo H. Neurologic complications and outcomes of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 in Korean children. J Korean Med Sci. 2012. 27:402–407.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download