Abstract

Endotoxins are known to be associated with the occurrence of various chronic diseases. This study was conducted to investigate the role of endotoxins in the pathogenesis of colon polyps through a case-control study. A total of 145 subjects (74 subjects in the polyp group and 71 subjects in the control group) had undergone a colonoscopy. Age, body mass index (BMI) and endotoxin levels were found to be significantly higher in the polyp group than in the control group. The endotoxin level was still significantly higher in the polyp group than in the control group, even after age and BMI had been adjusted (polyp group 0.108 ± 0.007 EU/mL, control group 0.049 ± 0.008 EU/mL, P < 0.001). In subgroup analysis, the endotoxin level significantly increased in accordance with the number of colon polyps (one-polyp group, 0.088 ± 0.059 EU/mL; two-polyp group, 0.097 ± 0.071 EU/mL; three-or-more-polyp group, 0.149 ± 0.223 EU/mL). The endotoxin levels also significantly increased in groups with tubular adenoma with high-grade dysplasia (hyperplastic polyp group, 0.109 ± 0.121 EU/mL; tubular adenoma with low grade dysplasia group, 0.103 ± 0.059 EU/mL; tubular adenoma with high grade dysplasia group, 2.915 ± 0.072 EU/mL). In conclusion, the serum level of endotoxins is quantitatively correlated with colon polyps.

Endotoxins are integral components of the cell membrane of Gram-negative bacteria. They are comprised of proteins, lipids and lipopolysaccaride (LPS); and LPS has been known to determine the biological properties of bacterial endotoxins (1). Endotoxins are associated with the pathophysiology of various chronic diseases such as atherosclerosis, diabetes and cancer (2). These diseases are known to be caused by endotoxins via a mechanism wherein endotoxins penetrate through the loosened intestinal mucosa and cause intestinal endotoxemia, which is in turn recognized by macrophages and causes various inflammation and immune reactions (3).

As to whether or not endotoxins are related to cancer, studies on their cancer risk are inconsistent depending on the organ. Many studies have reported that lung cancer risk was lower in patients exposed to endotoxins. The results were inconsistent for cancers other than lung cancer (4). As more studies report that endotoxins reduce cancer risk, the occurrence of other studies using endotoxins for cancer treatment has increased. However, due to severe complications, endotoxins have not been applied in clinical practice (5, 6).

Studies that reported an increase in the occurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma in rats that received LPS, or an increase in colon cancer risk in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases, suggest that endotoxins increase the risk of gastrointestinal cancer (7). In the pathogenesis of gastrointestinal malignancy, chronic inflammation plays an important role. According to its mechanism, a vast quantity of LPS-rich bacteria provides a suitable environment for chronic inflammation in the gastrointestinal tract, and gastrointestinal mucosal cells undergo malignant transformation via interactions among various pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines and transcriptional regulators (8).

This study was conducted to investigate the correlation of endotoxins with colon polyp by measuring the endotoxin level in patients with a colon polyp, a precancerous lesion of colon cancer, and to investigate the role of endotoxins in the reduction of colon cancer risk.

This study was conducted on patients aged 20 yr or older who had undergone a colonoscopy in the Uijeongbu St. Mary's Hospital of the Catholic University of Korea between March and April 2011. The patients, who had a colon polyp, as revealed in the colonoscopy, were assigned to the polyp group and the patients without polyp were assigned to the control group. As patients with glucose level higher than normal might affect the endotoxin level, patients with diabetes or a fasting glucose level ≥ 100 mg/dL were excluded. Patients who were using aspirin or other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs were also excluded.

For endotoxin detection, kinetic turbidimetric assay (KTA) and limulus amebocyte lysate (LAL) reagent KTA2 (Charles River Lab, Wilmington, MA, USA) were used. For each patient, 3 mL of blood was collected in a sodium heparin vacuum tube, centrifuged with 6,000 rpm for three minutes. The separated plasma was diluted 10 times in a new polystyrene tube. Therefore, 100 µL plasma was diluted with 900 µL dispersing agent (BD 100 buffer, Charles River Lab, Wilmington, MA, USA).

Before the process, the tube had been treated with heat inactivation for 10 min at 75℃, and then the treated tube was cooled slowly in ice or a freezer for 10 min. Endotoxin was measured instantly in most cases. For the rest of the cases, samples were stored at -20℃ to -70℃ and endotoxin was measured within seven days.

Standard endotoxin powder of 50 EU/mL was dissolved in LAL reagent water (LRW, Charles River Lab, Wilmington, MA, USA), and afterwards this standard solution was diluted to 5, 0.5, 0.05, and 0.005 EU/mL. In each process, samples were vortexed for 2 min, but only the solution of 50 EU/mL was vortexed violently for 5 min (Fig. 1).

The standard solution and plasmas were divided in 96 well plates. To avoid optical interference, each sample was treated by spike. Recovery of the spiked values in the potency verification phase must be within 50% to 200%. For spike-treatment, 10 µL of spike was put into the well of 5 EU/mL standard 1, after which LAL reagent was dissolved. In other words, we put 5.2 mL LRW into LAL reagent powder and used it after waiting 3-5 min. The vial was spun slowly until the powder was dissolved in LRW. After 3 min, it was completely dissolved and became transparent. After the LAL reagent was completely dissolved, 100 µL of LAL reagent was put into the plate within a short period of time for each one, including the standard solution and sample. After the process, the plate was put into a spectrophotometer (Endo-Chek™ from Diatech Korea Co. Ltd., Seoul, Korea) and the endotoxin concentration of each sample was measured (Fig. 1).

Medical history, family history, alcohol consumption, smoking habits and daily exercise habits were surveyed using a questionnaire. The patient's height (cm) and weight (kg) were measured to calculate the body mass index (kg/m2). The percent of body fat (%) was measured through a bioelectric impedance analysis. The waist circumference (cm) was measured at the belly level. The blood pressure was measured using a mercury sphygmomanometer after the patient relaxed for at least 10 min.

SPSS for Windows Version 15.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis. The patients' demographic characteristics were expressed in terms of mean ± standard deviation. A comparative analysis of each group's mean value was performed using an unpaired t-test. An ANOVA was conducted to analyze the factors associated with colon polyp. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of Uijeongbu St. Mary's Hospital of the Catholic University of Korea (IRB No. UC10TISI0147). All of the study subjects completed an informed consent form before participating in the study. The informed consent was confirmed by the board.

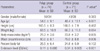

A total of 145 patients was comprised of 74 patients (24 of which were females) in the polyp group and 71 patients (28 of which were females) in the control group. No statistical difference between the two groups was found in the sex ratio, height, weight or % body fat. However, age, BMI and waist circumference were significantly higher in the polyp group than in the control group. The endotoxin level was 0.11 ± 0.086 EU/mL in the polyp group and 0.04 ± 0.005 EU/mL in the control group, whereby showing a significantly higher level in the polyp group (Table 1).

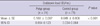

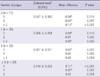

The subjects were divided into 4 subgroups according to their number of polyps: a patient group with no polyp, a group with 1 polyp, a group with 2 polyps, and a group with 3 or more polyps. Subsequently, the endotoxin level was analyzed after age, BMI and waist circumference were adjusted. The adjusted mean levels of endotoxin in the polyp group was 0.108 and 0.049 in the control group, which showed a significant difference in the endotoxin levels of the groups, even though the two factors had been adjusted (Table 2). The endotoxin level was shown to be significantly lower in the subgroup with no polyp than in the other three subgroups. The endotoxin level was shown to be significantly higher in the subgroup with three or more polyps than in the other 3 subgroups. No statistical difference was found between the subgroup with one polyp and the subgroup with two polyps (Table 3).

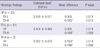

The subjects with polyps were classified again according to histologic findings, followed by an analysis of the endotoxin level of each subgroup. The subjects with polyps were divided into three subgroups: 1) HP subgroup with chronic inflammation and hyperplastic polyps without clinical malignant potency; 2) TA-L subgroup with tubular adenoma with low-grade dysplasia; and 3) TA-H subgroup with tubular adenoma with high-grade dysplasia. The endotoxin level was significantly higher in the TA-H subgroup than in the other subgroups. No significant difference was found between the HP subgroup and the TA-L subgroup (Table 4).

Endotoxins are associated with the occurrence and aggravation of various chronic diseases. Paradoxically, however, many studies reported that endotoxins reduced cancer (9, 10). The role of endotoxins on carcinogenesis - which is still controversial - has been mainly attributable to the complex interactions between the innate and adaptive immune systems (11). LPS fluxed into the blood stream binds to LPS-binding proteins (LBPs) and is transferred to CD14 proteins. The CD14-LPS complex activates the Toll-like receptors (TLRs) present in macrophages and other cell surfaces, and the activated macrophages and other cells secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1, and IL-6 (12). Immune reactions to LPS are mainly believed to activate Th1 cells and exhibit antitumor activity (13). In the gastrointestinal tract, unlike in other organs, cancer risk has been believed to increase through cellular transformation, the inhibition of apoptosis and angiogenesis via cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 generation caused by Th1 cell activation in a chronic inflammatory environment (8). Although further epidemiologic and experimental investigations are required to reveal endotoxins' dose-effect or its relation to exposure timing, at the present time, the relationship between endotoxins and cancer seems to vary depending on the organ.

This study was conducted to investigate the correlation of endotoxins with colon polyps, the well-known precancerous lesions of colon cancer. In most cases, colon cancer occurs in the adenomatous polyp (14). The relationship between hyperplastic polyp and colon cancer, although controversial, has been known to have nearly no malignant potential (15). The malignant potential of colon polyp varies depending on their histology, number and size (14).

The correlation between endotoxins and colon cancer has not been well investigated in previous studies. In this study, the endotoxin level was seen to be higher as the number of colon polyps increased. The endotoxin level also increased in patients with tubular adenoma with high-grade dysplasia, which has a high malignancy potential. The aforementioned results may suggest that endotoxin is a risk factor for colon cancer. Despite its statistical significance, however, a more careful statistical analysis is required, as there were not enough patients with high-grade dysplasia in this study. To achieve this, a further long-term study would need to be conducted on a larger scale.

Age and obesity are known risk factors for colon cancer. In this study, although age and BMI were significantly higher in the polyp group, and even after age and BMI were adjusted and analyzed, the endotoxin level was still seen to be significantly higher in the polyp group than in the control group.

This study had a few limitations. Firstly, as this was a cross-sectional study, the transient increase in the endotoxin level could not be ruled out. Secondly, a significant difference in the age and BMI of the two groups was present. Thirdly, there were not enough subjects in the high grade dysplasia group with a high risk of colon cancer.

In conclusion, the serum level of endotoxins is correlated with colon polyps.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Campbell NA, Reece JB, Urry LA, Cain ML, Wasserman SA, Minorsky PV, Jackson RB. Biology. 2008. 8th ed. San Francisco, CA: Benjamin Cummings;452–555.

2. Chang S, Li L. Metabolic endotoxemia: a novel concept in chronic disease pathology. J Med Sci. 2011. 3:191–209.

3. Simpson S, Ash C, Pennisi E, Travis J. The gut: inside out. Science. 2005. 307:1895.

4. Lundin JI, Checkoway H. Endotoxin and cancer. Environ Health Perspect. 2009. 117:1344–1350.

5. de Bono JS, Dalgleish AG, Carmichael J, Diffley J, Lofts FJ, Fyffe D, Ellard S, Gordon RJ, Brindley CJ, Evans TR. Phase I study of ONO-4007, a synthetic analogue of the lipid A moiety of bacterial lipopolysaccharide. Clin Cancer Res. 2000. 6:397–405.

6. Otto F, Schmid P, Mackensen A, Wehr U, Seiz A, Braun M, Galanos C, Mertelsmann R, Engelhardt R. Phase II trial of intravenous endotoxin in patients with colorectal and non-small cell lung cancer. Eur J Cancer. 1996. 32A:1712–1718.

7. Yang JM, Han DW, Xie CM, Liang QC, Zhao YC, Ma XH. Endotoxins enhance hepatocarcinogenesis induced by oral intake of thioacetamide in rats. World J Gastroenterol. 1998. 4:128–132.

8. Macarthur M, Hold GL, El-Omar EM. Inflammation and Cancer. II. Role of chronic inflammation and cytokine gene polymorphisms in the pathogenesis of gastrointestinal malignancy. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004. 286:G515–G520.

9. Astrakianakis G, Seixas N, Camp J, Smith TJ, Bartlett K, Checkoway H. Cotton dust and endotoxin levels in three Shanghai textile factories: a comparison of samplers. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2006. 3:418–427.

10. Werling D, Jungi TW. TOLL-like receptors linking innate and adaptive immune response. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2003. 91:1–12.

11. Schmidt C. Immune system's Toll-like receptors have good opportunity for cancer treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006. 98:574–575.

12. Poltorak A, He X, Smirnova I, Liu MY, Van Huffel C, Du X, Birdwell D, Alejos E, Silva M, Galanos C, et al. Defective LPS signaling in C3H/HeJ and C57BL/10ScCr mice: mutations in Tlr4 gene. Science. 1998. 282:2085–2088.

13. Hong S, Qian J, Yang J, Li H, Kwak LW, Yi Q. Roles of idiotype-specific T cells in myeloma cell growth and survival: Th1 and CTL cells are tumoricidal while Th2 cells promote tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2008. 68:8456–8464.

14. Cappell MS. The pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and diagnosis of colon cancer and adenomatous polyps. Med Clin N Am. 2005. 89:1–42.

15. Blue MG, Sivak MV Jr, Achkar E, Matzen R, Stahl RR. Hyperplastic polyps seen at sigmoidoscopy are markers for additional adenomas seen at colonoscopy. Gastroenterology. 1991. 100:564–566.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download