Abstract

IMR is useful for assessing the microvascular dysfunction after primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). It remains unknown whether index of microcirculatory resistance (IMR) reflects the functional outcome in patients with anterior myocardial infarction (AMI) with or without microvascular obstruction (MO).This study was performed to evaluate the clinical value of the IMR for assessing myocardial injury and predicting microvascular functional recovery in patients with AMI undergoing primary PCI. We enrolled 34 patients with first anterior AMI. After successful primary PCI, the mean distal coronary artery pressure (Pa), coronary wedge pressure (Pcw), mean aortic pressure (Pa), mean transit time (Tmn), and IMR (Pd * hyperemic Tmn) were measured. The presence and extent of MO were measured using cardiac magnetic resonance image (MRI). All patients underwent follow-up echocardiography after 6 months. We divided the patients into two groups according to the existence of MO (present; n = 16, absent; n = 18) on MRI. The extent of MO correlated with IMR (r = 0.754; P < 0.001), Pcw (r = 0.404; P = 0.031), and Pcw/Pd of infarct-related arteries (r = 0.502; P = 0.016). The IMR was significantly correlated with the ΔRegional wall motion score index (r = -0.61, P < 0.01) and ΔLeft ventricular ejection fraction (r = -0.52, P < 0.01), implying a higher IMR is associated with worse functional improvement. Therefore, Intracoronary wedge pressures and IMR, as parameters for specific and quantitative assessment of coronary microvascular dysfunction, are reliable on-site predictors of short-term myocardial viability and Left ventricle functional recovery in patients undergoing primary PCI for AMI.

Early restoration of epicardial coronary blood flow reduces infarct size in patients with acute myocardial infarctions (AMI) and has a beneficial effect on healing of the myocardium and left ventricular (LV) remodeling. However, successful restoration of epicardial flow does not induce optimal reperfusion of myocardial tissue and microvascular function, LV remodeling, and improved clinical outcome (1). As a consequence, complete restoration of infarct-related arterial patency and microvascular integrity has important prognostic significance in patients after an AMI (2). Microvascular obstruction (MO), or no reflow phenomenon, defines an area within an AMI that has undergone cardiomyocyte necrosis, as well as severe and irreversible microcirculation damage (3). Microvascular obstruction is associated with poor prognosis and worse LV remodeling. Infarct extent and MO can reliably be detected by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (4). However, this information is not readily available in clinical practice, and other prognostic measures have been proposed to meet such limitations. The thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) flow grade, the TIMI blush grade, the corrected TIMI frame count, and the coronary flow reserve (CFR) have all been investigated and known to be related to outcome of AMI patients (5, 6). With recent technological advances, it is now possible to measure pressure and estimate coronary artery flow simultaneously with a single pressure-temperature sensor-tipped coronary wire (7, 8). The single pressure-temperature sensor-tipped coronary wire has additional advantage of allowing assessment of several potentially useful clinical indices. It has been reported that IMR was a predictor of microvascular damage after myocardial infarction and predictor of left ventricular functional recovery after 3 months (9, 10). However, our study periods are 6 months, thereby more reliable results can be derived from our study. Out study can be more reliable for 6 months period of study more than 3 months. It also has been reported that IMR was a predictor of myocardial viability and left ventricular functional recovery in acute myocardial infarction (11). Past study used 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography to quantify the myocardial variability, and few IMR study using MRI has been done (12). We quantified myocardial viability by MRI and it has relatively free methods-limitation. Studies with animal models have shown that an index of microcirculatory resistance (IMR) correlates with true microvascular resistance, and unlike CFR, it is independent of the epicardial arteries (7, 8, 12, 13). Therefore, a relationship between the perfusion and infarct size can be assumed, but whether or not the microvascular hemodynamic parameter can reliably represent the extent of necrosis in the infarct territory remains unknown. Furthermore, previous studies have not focused on the indices which specifically represent cardiac microvascular status and can thus accurately predict the extent of myocardial injury during the acute phase of an AMI. We assessed the clinical value of the IMR to assess the micro-vascular dysfunction and predicting microvascular functional recovery in patients with AMI who underwent primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

We prospectively studied 34 consecutive patients who were referred for PCI following a first AMI. All patients were treated by successful primary PCI, defined as TIMI flow grade > 2 and subsequent stent implantation with residual stenosis of < 25%. Inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) an episode of chest pain > 30 min, 2) an ECG showing ST-elevation ≥ 2 mm on a precordial lead, and 3) a 3-fold increase in cardiac enzymes above the normal range, and 4) a regional wall motion abnormalities in ≥ 3 segments on resting echcardiography. The exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) cardiogenic shock, 2) left main disease or 3-vessel disease, 3) old MI, 4) visible collateral circulation on coronary artery angiography (after successful PCI, we used pressure-temperature sensor-tipped coronary wire), and 5) patients with contraindications for MRI. Patients were treated with aspirin, heparin, abciximab, clopidogrel, statins, beta-blockade, and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors.

All patients underwent primary PCI with catheterization for monitoring IMR between 1 and 5 hr after symptoms onset, then underwent cardiac MRI at least 72 hr, but within 7 days after primary PCI. All cardiac MRI were supervised and analyzed by one operator who was blinded to IMR and vice versa.

The MRI was performed on a 1.5-T scanner (Siemens Sonata; Erlangen, Germany) utilizing a 12-channel body array surface coil. All patients were examined in the supine position, and contrast material was injected via cephalic vein. Scout images were obtained, and typical imaging parameters were a 380 * 320 mm2 field of view (FOV), a 256 * 159 matrix, an 8-mm slice thickness, a 2-mm slice gap, a 70° flip angle, a 1.51-ms echo time, and a 45.15-ms repetition time. Six short-axis slices were chosen at equal distances along the LV long axis for first-pass perfusion imaging with an electrocardiographically-triggered saturation recovery ultra-fast gradient echo (turbo-flash) sequence (repetition time/echo time/inversion time, 188 ms/0.96 ms/100 ms; flip angle, 15°). A 96 * 128 matrix, an 8-mm slice thickness, and a 309 * 380 mm2 FOV were used. A bolus of gadopentetate dimeglumine in a dose of 0.1 mM/kg of body weight was injected intravenously at 3 mL/s, followed by 20 mL of normal saline using a MRI-compatible power injector. A second bolus of Gd-DTPA (0.1 mM/kg of body weight) was administered, and late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) images were obtained 12 to 15 min after the second contrast administration. With a flip angle of 45°, delayed contrast-enhanced images covering the left ventricle from the base to the apex in the short axis view (slice thickness, 8 mm; gap, 2 mm) were obtained 15 min after perfusion imaging with breath-hold and a phase-sensitive inversion recovery steady state-free precision sequence with repetition and echo times of 680 ms and 1.26 ms, respectively. The typical imaging parameters were a 308 * 340 mm2 FOV and a 184 * 256 matrix.

All MRI data was obtained on the cine images using the MASS software package (Medis, Leiden, The Netherlands). On all the short-axis cine slices, the endocardial and epicardial borders were outlined manually on the end-diastolic and -systolic images. We divided the short axis into 12 equiangular segments to measure the LV segmental function, and the LV volumes and LV ejection fractions (LVEF) were calculated. We assessed delayed enhancement images and infarct size as previously described (14). The total infarct size was calculated as the percentage of the LV mass, and transmural extent of infarction was calculated by dividing the hyper-enhanced area by the total area of the predefined segment (%). A transmurality score was calculated in each patient, which was expressed as the sum of segments with > 75% infarcted myocardium as a percentage of the total number of segments scored. On the delayed enhancement images, the MO was defined as any region of hypo-enhancement within the hyper-enhanced infarcted area, and was included in the calculation of the total infarct size. The extent of MO was calculated in each patient, and measured percent by dividing number of MO segment by number of total segment. All MRI measurements of the LVEF and extent of MO and infarct size were reviewed by two independent blinded observers. The intra-class correlation coefficients for the intra- and inter-observer agreement for these parameters were all > 0.9.

Intracoronary pressure parameters were measured in each patient after PCI using previously described principles (7). With commercially available software (Radi Medical Systems, Uppslae, Sweden), the shaft of the pressure wire can act as a proximal thermistor, sensor near the tip of the wire simultaneously measured the pressure and temperature acting as a distal thermistor. Thermodilution technique was used to check the the transit time of room temperature when saline was injected down to coronary arteries (8). 3 mL aliquots of room temperature saline was administered to the coronary artery, and the resting mean transit time (baseline mean transit time [bTmn]) was measured. Steady state of maximal hyperemia was induced by intravenous infusion of adenosine (140 µg/kg/min). Three additional 3 mL aliquots of room temperature saline was injected, and the hyperemic mean transit time (hTmn) was measured. The simultaneous measurements of mean aortic pressure (Pa, by guiding catheter) and mean distal coronary pressure (Pd, by pressure wire) were also obtained during the resting state and maximal hyperemic state. The CFR thermo was calculated, dividing the resting hTmn by the bTmn. The IMR was defined as the simultaneously measured distal coronary pressure divided by the inverse of the hTmn (12, 13).

Echocardiographic images were obtained in the standard parasternal long, short axes and apical 4- and 2-chamber views utilizing digital Vivid 7 ultrasound equipment with a combined tissue imaging 2.5-4.0 MHz transducer (GE, Milwaukee, WI, USA). At least three cardiac cycles were monitored at the LV base, midpapillary muscle level, and apex for wall motion assessment. No intravenous contrast agent was used. After 6 months, an blinded expert reader obtained measurements off-line from the parasternal and apical windows. Two-dimensional (2D) ventricular volumes and LVEF were measured from the 4- and 2-chamber areas using the modified Simpson's rule. The left ventricle was divided into 16 segments. The myocardial motion of each segment was evaluated according to the American Society of Echocardiography wall motion scoring system and the regional wall motion score index (RWMSI) was calculated. The two observers were blinded to the echocardiographic investigations, The LVEF was calculated by substracting the baseline LVEF from the follow-up LVEF, and ΔRWMSI was calculated by substracting the baseline LVEF from the follow-up RWMSI.

The values are reported as the mean ± SD or median (25th-75th percentiles) for continuous variables and as frequency for categorical variables. The correlations between the extent of MO and coronary physiologic parameters were calculated by using simple linear regression analysis to identify parameters which are independently associated with the extent of MO, being determined by cardiac MRI. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to assess the relationship between coronary hemodynamic pressure parameters and the presence of MO. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All calculations were generated by SPSS 12.0 for Windows.

Of the 34 patients included in the study (mean age, 57 ± 4 yr), 20 were men, 9 had hypercholesterolemia, 8 had diabetes mellitus, 8 had a history of hypertension, and 14 were smokers. The mean time from the onset of symptoms to reperfusion was 194 min, and standard deviation was 123 min. The patients were divided into the following two groups: no MO group (MRI with homogeneous enhancement of the myocardium; n = 16); and the MO group (MRI with hypo-enhanced region; n = 18; Table 1), according to the presence of MO on MRI. An MRI was performed 6 ± 4 days after the acute event. There were no differences in the baseline characteristics and hemodynamic variables between the two groups.

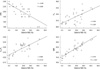

Intracoronary pressure parameters data showed that the increasing extent of MO was associated with higher hyperemic mean transient time and decreased CFR. The IMR was significantly higher in the MO group than the no MO group. Although the Pa and Pd values were comparable between the two groups, the mean Pcw was significantly higher in the MO group. Thus, the elevation of the mean Pcw appears, in part, to explain an increase in Pcw/Pa in the MO patients (Table 2). Stepwise multivariate linear regression analysis was performed to identify the factors that were closely related to IMR, and the presence of MO was proven to be related to IMR (T = 3.4; P < 0.01), and no MO had the strongest relationship to IMR. The extent of MO was correlated with IMR (r = 0.754; P < 0.001), Pcw (r = 0.404; P = 0.031), and Pcw/Pa of the infarct-related artery (r = 0.502; P = 0.016). An inverse relationship was observed between the extent of MO and CFR (r = -0.368; P = 0.029; Fig. 1).

All hospitalized patients were evaluated with echocardiography, and follow-up echocardiography was additionally performed after average 6.3 months. The values for the LVEF at the 6-month follow-up was significantly higher in the no MO group than in the MO group, and no MO group presented higher ΔLVEF and ΔRWMSI than the MO group. We compared the relationship between IMR and the magnitude of LV functional improvement. The IMR was significantly correlated with ΔRWMSI (r = -0.61, P < 0.01; Fig. 2A) and ΔLVEF (r = -0.52, P < 0.01), implying a higher IMR is associated with worse functional improvement. When the ΔRWMSI was compared in patients with TIMI-3 flow, there was no relationship among the patients with TIMI-3 flow (r = 0.32, P > 0.05). So close correlation existed between the IMR and ΔRWMSI in the AMI patients, we could derive an intracoronary wedge pressure index (Pcw/Pa). The parameter was significantly lower in the no MO group than the MO group (0.27 ± 0.83 vs 0.33 ± 0.17, P < 0.01). There was a close inverse relationship between Pcw/Pa, IMR, and ΔRWMSI (Fig. 2). On multivariate analysis including infarct size and TIMI grade, IMR was the strongest independent predictor of ΔRWMSI (r = -0.61, P < 0.001).

Our study examined the predictive ability of microcirculatory resistance (IMR) in MI patients treated with PCI for recovery at 6 months. Patients who had PCI were studied by using Gd-enhanced MR to evaluate infarct size and enhancement which reflects MO. Echocardiography was performed after MI and then 6 months later. Our study showed that hemodynamic indices (IMR, Pcw, and Pcw/Pa) reflected the extent of MO and functional recovery at 6 months after MI. Recovery of function and development of remodeling after MI are strongly related to perfusion at the microcirculatory level. Recent MRI investigations have shown that MO, irrespective of infarct size, is a strong predictor of cardiovascular events after infarction (15). The no-reflow phenomenon is thus an important prognostic factor (16), but its detection requires additional investigations, such as MRI or myocardial contrast echocardiography. The findings of this study suggest that microcirculatory reactivity assessed with a coronary guide wire indicates the amount of microvascular injury and clarifies why coronary hemodynamic parameters can be used as a prognostic parameter for myocardial functional recovery. The CFR has been reported that the increased flow velocity during the acute phase of an AMI limits the accurate evaluation of the extent of microvascular injury (8, 17). Although the role of Pcw in protecting the myocardium and in reflecting myocardial injury is fraught with controversy, a recent study reported that the rise of coronary wedge pressure reflects the level of microvascular injury, and that the coronary zero flow pressure (Pzf) in AMI patients who underwent PCI within 24 hr of the onset of chest pain is correlated with the microvascular dysfunction induced by myocardial injury (18, 19). The results of our study support the findings of previous studies by demonstrating the coronary artery wedge pressure and correction of coronary artery wedge pressure to coronary perfusion pressure (Pcw/Pa) as useful indicators for ischemic microvascular dysfunction. The IMR is a novel index that represents microvascular integrity; the IMR is a better predictive parameter of myocardial damage than other parameters for evaluating the microvasculature after primary PCI (12, 13). The indices of various coronary artery microvascular abnormalities were measured by intra-coronary pressure wires within the coronary arteries and then compared to MR images, the current standard method of evaluation for myocardial injury. The present study has shown that the intracoronary hemodynamic indices (Pcw and Pcw/Pa), measured by the intracoronary pressure, adequately represent myocardial injury. In the presence of detectable significant myonecrosis, we presumed that increasing IMR indicates microvascular dysfunction after PCI. The results of our study also support IMR as a useful indicator for assessing microvascular dysfunction after PCI during the acute phase of myocardial ischemia. As an invasive indicator, IMR is expected to play an important role in assessing microvascular injury and prognosis, and in planning treatment procedures at earlier stages of disease. Also, Pcw/Pa and CFR thermo can be obtained simultaneously by an intracoronary pressure wire, providing additional information about the degree of microvascular dysfunction and myocardial injury. Furthermore, simultaneous measurement of intracoronary pressure parameters and IMR may provide a simple means for comprehensive and specific assessment of intracoronary hemodynamics at both the epicardial and microvascular levels, respectively. MO with a subsequent high impedance results in the inability to squeeze blood forward into the venous circulation during systole, and consequently the blood will be pushed back into the epicardial coronary arteries (20).

We acknowledge limitations of the study. First, the hemodynamic characteristics of coronary arteries and their clinical significance and outcome can vary according to the different infarct-related arteries and the location of the lesion. In light of such a fact, the study had excluded patients with anatomic variations and whose lesions were located at the distal portion. Secondly, there is a controversy about the effect of epicardial artery occlusion when measuring the microvascular resistance using IMR. When the occlusion is severe, the simplified equation of this study does not take collateral circulations into consideration, resulting overestimation of microvascular resistance. However, in our study, the measurements were obtained after successful removal of epicardial occlusion through intervention, thus the effect of epicardial artery occlusion is thought to be minimal. Moreover, transient vasospasm and distal microemboli during the acute phase of an MI can increase microvascular resistance, but it does not always result in irreversible necrosis of the myocardium. Third limitation is that there is no TIMI frame count, myocardial blush score, TIMI flow, and specific follow up wall motion score. Such a fact can serve as a limitation in the evaluation of myocardial dysfunction using the IMR as a measure of microvascular resistance during the acute phase of an AMI.

A close correlation between the size of the anatomic MO and necrosis was already proved to be related to ischemic cardiac injury. In the present study, we showed that the extent of MO (% of microvascular damage) assessed by cardiac MRI correlated well with intracoronary pressure parameters, such as IMR and Pcw/Pa. Furthermore, after adjusting the extent of MO, IMR and Pcw/Pa were able to predict myocardial injury during the acute phase of an AMI.

In conlusion, intracoronary wedge pressures and IMR, as parameters for specific and quantitative assessment of coronary microvascular dysfunction, are reliable on-site predictors of short-term myocardial viability and LV functional recovery in patients undergoing primary PCI for AMI.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Correlation between intracoronary pressure parameters, index of microcirculatory resistance (IMR) and extent of microvascualr obstruction (MO). There was significant correlation between IMR, intracoronary pressure parameters and extent of MO. Open circles represent patients with MO as measured by cardiac MRI. CFR, coronary flow reserve; Pa, mean aortic pressure; Pcw, coronary wedge pressure. |

| Fig. 2Correlation between ΔRWMSI and IMR (A) and Pcw/Pa (B). There was significant inverse correlation between ΔRWMSI and IMR. Thus, higher IMR is associated with the lower ΔRWMSI, implying the worse functional outcomes. Significant correlation was also found between ΔRWMSI and Pcw/Pa. Triangles indicate patients with MO, and circles represent patients with no MO. Δ (delta), the difference of the values at Follow up day minus at baseline day; RWMSI, regional wall motion score index; IMR, index of microcirculatory resistance; Pcw/Pa, coronary wedge pressure to mean aortic pressure ratio. |

Table 2

Intracoronary pressure measurements

Values are expressed as mean ± SD or n (%). CFRthermo, thermodilution coronary flow reserve; IMR, index of microcirculatory resistance; Pa, mean aortic pressure; Pcw, coronary wedge pressure; Pcw/Pa, coronary wedge pressure to mean aortic pressure ratio; Pd, mean distal coronary attery pressure; Tmn, mean transit time; MO, microvascular obstruction.

References

1. Ito H, Tomooka T, Sakai N, Yu H, Higashino Y, Fujii K, Masuyama T, Kitabatake A, Minamino T. Lack of myocardial perfusion immediately after successful thrombolysis. A predictor of poor recovery of left ventricular function in anterior myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1992. 85:1699–1705.

2. Gibson CM, Schomig A. Coronary and myocardial angiography: angiographic assessment of both epicardial and myocardial perfusion. Circulation. 2004. 109:3096–3105.

3. Rochitte CE, Lima JA, Bluemke DA, Reeder SB, McVeigh ER, Furuta T, Becker LC, Melin JA. Magnitude and time course of microvascular obstruction and tissue injury after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1998. 98:1006–1014.

4. Wu KC, Zerhouni EA, Judd RM, Lugo-Olivieri CH, Barouch LA, Schulman SP, Blumenthal RS, Lima JA. Prognostic significance of microvascular obstruction by magnetic resonance imaging in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1998. 97:765–772.

5. Gibson CM, Cannon CP, Murphy SA, Marble SJ, Barron HV, Braunwald E. Relationship of TIMI myocardial perfusion grade to mortality after administration of thrombolytic drugs. Circulation. 2000. 101:125–130.

6. Fearon WF, Farouque HM, Balsam LB, Caffarelli AD, Cooke DT, Robbins RC, Fitzgerald PJ, Yeung AC, Yock PG. Comparison of coronary thermodilution and Doppler velocity for assessing coronary flow reserve. Circulation. 2003. 108:2198–2200.

7. De Bruyne B, Bartunek J, Sys SU, Pijls NH, Heyndrickx GR, Wijns W. Simultaneous coronary pressure and flow velocity measurements in humans: feasibility, reproducibility, and hemodynamic dependence of coronary flow velocity reserve, hyperemic flow versus pressure slope index, and fractional flow reserve. Circulation. 1996. 94:1842–1849.

8. Pijls NH, De Bruyne B, Smith L, Aarnoudse W, Barbato E, Bartunek J, Bech GJ, Van De Vosse F. Coronary thermodilution to assess flow reserve: validation in humans. Circulation. 2002. 105:2482–2486.

9. Fearon WF, Shah M, Ng M, Brinton T, Wilson A, Tremmel JA, Schnittger I, Lee DP, Vagelos RH, Fitzgerald PJ, et al. Predictive value of the index of microcirculatory resistance in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008. 51:560–565.

10. McGeoch R, Watkins S, Berry C, Steedman T, Davie A, Byrne J, Hillis S, Lindsay M, Robb S, Dargie H, et al. The index of microcirculatory resistance measured acutely predicts the extent and severity of myocardial infarction in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. JACC Cardiovascular Interventions. 2010. 3:715–722.

11. Lim HS, Yoon MH, Tahk SJ, Yang HM, Choi BJ, Choi SY, Sheen SS, Hwang GS, Kang SJ, Shin JH. Usefulness of the index of microcirculatory resistance for invasively assessing myocardial viability immediately after primary angioplasty for anterior myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2009. 30:2854–2860.

12. Fearon WF, Balsam LB, Farouque HM, Caffarelli AD, Robbins RC, Fitzgerald PJ, Yock PG, Yeung AC. Novel index for invasively assessing the coronary microcirculation. Circulation. 2003. 107:3129–3132.

13. Ng MK, Yeung AC, Fearon WF. Superior reproducibility and less hemodynamic dependence of index of microcirculatory resistance compared with coronary flow reserve. Circulation. 2006. 113:2054–2061.

14. Kim RJ, Shan DJ, Judd RM. How we perform delayed enhancement imaging. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2003. 5:505–514.

15. Tarantini G, Cacciavillani L, Corbetti F, Ramondo A, Marra MP, Bacchiega E, Napodano M, Bilato C, Razzolini R, Iliceto S. Duration of ischemia is a major determinant of transmurality and severe microvascular obstruction after primary angioplasty: a study performed with contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005. 46:1229–1235.

16. Ito H, Maruyama A, Iwakura K, Takiuchi S, Masuyama T, Hori M, Higashino Y, Fujii K, Minamino T. Clinical implications of the 'no reflow' phenomenon. A predictor of complications and left ventricular remodeling in reperfused anterior wall myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1996. 93:223–228.

17. Lepper W, Hoffmann R, Kamp O, Franke A, de Cock CC, Kühl HP, Sieswerda GT, Dahl J, Janssens U, Voci P, et al. Assessment of myocardial reperfusion by intravenous myocardial contrast echocardiography and coronary flow reserve after primary percutaneous transluminal coronary angiography in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2000. 101:2368–2374.

18. Yamamoto K, Ito H, Iwakura K, Shintani Y, Masuyama T, Hori M, Kawano S, Higashino Y, Fujii K. Pressure-derived collateral flow index as a parameter of microvascular dysfunction in acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001. 38:1383–1389.

19. Lee CW, Park SW, Cho GY, Hong MK, Kim JJ, Kang DH, Song JK, Lee HJ, Park SJ. Pressure-derived fractional collateral blood flow: a primary determinant of left ventricular recovery after reperfused acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000. 35:949–955.

20. Gerber BL, Rochitte CE, Melin JA, McVeigh ER, Bluemke DA, Wu KC, Becker LC, Lima JA. Microvascular obstruction and left ventricular remodeling early after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2000. 101:2734–2741.

21. Yoon MH, Tahk SJ, Yang HM, Woo SI, Lim HS, Kang SJ, Choi BJ, Choi SY, Hwang GS, Shin JH. Comparison of accuracy in the prediction of left ventricular wall motion changes between invasively assessed microvascular integrity indexes and Fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2008. 102:129–134.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download