Abstract

A 62-yr-old man presented with a 5-yr history of intermittent abdominal distention and pain. These symptoms persisted for several months and subsided without treatment. A diagnosis of suspected small bowel lymphoma was made based on plain radiograph and computerized tomogram findings, and he was referred to our institution for further evaluation. Segmental resection of the small intestine was performed and the diagnosis of marginal zone B-cell lymphoma associated with amyloidosis was made. This is the first case of marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) in the small intestine associated with amyloidosis in Korea.

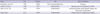

The extent of amyloid deposition is greatest in the small intestine (1, 2). Autopsy demonstrated that 31% of patients with systemic amyloidosis experienced amyloid deposition in the small intestine (1, 2), although localized amyloidosis of the small intestine remains very rare. Only four cases on localized small bowel amyloidosis have been reported (3-6). Amyloid deposits can mimic a tumor, and have occasionally been associated with gastrointestinal lymphoma (7-11), but localized amyloidosis associated with small intestine lymphoma is extremely rare. Only three cases reports have been published on small bowel localization of amyloidosis associated with lymphoma (7, 8, 10). Clincopathologic features of previously reported cases were summarized in Table 1.

We present an unusual case of intestinal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) with concurrent localized amyloidosis. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case report on localized intestinal amyloidosis associated with intestinal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of MALT in Korea.

A 62 yr-old man presented with a 5-yr history of intermittent abdominal pain associated with abdominal distention which waxed and waned without treatment on June 4, 2010. Ten days before presenting to our institution, he was urgently admitted to a local hospital with abdominal pain. Computerized tomography (CT) scan taken there revealed multi-focal enhancing small bowel wall thickening associated with skipped lesion sparing of the terminal ileum and the ileocecal valve. Inflammatory bowel disease was suggested as a preliminary diagnosis. He was subsequently referred to our hospital for further evaluation. On examination, he appeared ill but remained apyrexial. Abdominal examination elicited hypogastric guarding, pelvic tenderness and some rebound tenderness. Initial laboratory studies revealed severe thrombocytopenia of 4 × 103/mm2 without leukocytosis. Diagnostic and therapeutic segmental resection of the small intestine was subsequently performed on 14th June, 2010. Intraoperatively, the jejunum exhibited 30 cm segmental wall thickening, and a localized mass-like lesion was found in the ileum which caused luminal obstruction and multifocal bowel wall segmental thickening. Moreover, one enlarged mesenteric lymph node was identified and subsequently sent to our department for frozen diagnosis. Segmental resection of jejunum (about 40 cm in length) and ileum (about 1 m in length) was performed. The surgical specimen was fixed in 10% buffered formalin. Tissue samples were taken, processed for routine histology and embedded in paraffin. Five micrometer-thick sections were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin, Congo Red with and without KMnO4 (12). Immunohistochemistry was conducted with the avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex methods using antibody CD3 (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark, prediluted), CD20 (Dako, prediluted), CD23 (Dako, prediluted), CD5 (Dako, prediluted), cyclin D1 (Dako, prediluted), kappa (Dako, prediluted), lambda (Dako, prediluted), Ki-67 (Dako, prediluted). Unstimulated isolated bone marrow cells were cultured for 24 hr and G-banded according to standard procedures. Metaphases were analyzed and karyotyped according to the nomenclature system proposed by the International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature, 1995.

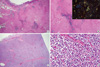

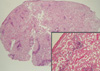

The gross specimen showed two segments of small intestine, measuring 1 m and 40 cm in length, respectively. The diameter and thickness of the intestinal segments varied greatly in size. The appearance of the overlying mucosa revealed a short linear and transverse ulceration in an irregular and thickened wall. Sections of the involved intestinal segment showed two different processes: first, we observed a homogeneous acidophilic substance (Fig. 1A, B). A Congo Red stain demonstrated doubly refractive property with polarized light (Fig. 1B, inset). Second, a diffuse proliferative lymphoid infiltrate spread through the intestinal wall up to the serosa (Fig. 1C). The lymphoid component was comprised mainly of small lymphocytes with round nuclei, often with a small central nucleoli, clumped chromatin with scanty basophilic cytoplasm admixed with plasma cells (Fig. 1D). Smaller lymphocytes without discernable cytoplasm and some large cells with oval and vesicular nuclei with prominent nucleoli. In addition, a monocytoid component was also found. No obvious lymphoepithelial lesion was identified and plasma cells with Dutcher bodies were occasionally seen. The excised mesenteric lymph node showed extensive amyloid deposits intermixed by small aggregates of lymphoid cells (Fig. 2). Most lymphocytes were stained positively with CD20 (Fig. 3A) but negative for CD3, CD5, CD23, and cyclin D1. The Ki-67 labeling index was low (less than 5%) (Fig. 3B). Kappa chain restriction was found in the plasma cells (Fig. 3C, D). There was no clinical evidence of systemic amyloidosis and renal function remained normal. Bone marrow biopsy showed no evidence of lymphoma or amyloid deposition whereas echocardiogram, rectal biopsy and abdominal fat aspirates were not performed. Cytogenetic study performed on bone marrow cells showed chromosomal abnormality. The karyotype was 46XY, inv(2)(p25q13)[14]/46,XY[16]. The serum total protein level was within the normal limits, and serum electrophoresis showed an IgM kappa monoclonal gammopathy. The patient received four cycles of chemotherapy (R-CVP) over 4 months and he is currently in remission.

The association of amyloidosis and gastrointestinal lymphoma is very rare and to our knowledge it has only been described in 8 reports (7, 8, 10, 11). Moreover, lymphadenopathy secondary to amyloid deposition in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma is also rare. On reviewing the Korean literature, we could not identify a report on such an association in intestinal lymphoma. Only one Korean case reported amyloidosis in the bone marrow associated with lymphoma but the histologic type could not be determined, because monotonous B-cells were only present in the bone marrow and only positive for CD20 (13). Our case is very unusual because localized amyloidosis was associated with low grade B-cell intestinal lymphoma.

This case represented a diagnostic challenge, because the amyloid could have displaced lymphomatous proliferation and produced a tumoral mass. Some area showed definite lymphotous infiltration, but some area showed extensive amyloid deposition with scarce lymphocytic infiltration. Moreover, one enlarged mesenteric lymph node was sent for frozen diagnosis. At that time, the diagnosis of lymphoma was not made, as the lymph node showed extensive amyloid deposits with interspersed aggregates of lymphoid cells. The detection of amyloid deposits in a lymph node biopsy should therefore raise the possibility of concurrent lymphoma. There are several case reports on localized amyloidosis in the gastrointestinal tract. Usually, these cases are diagnosed by endoscopic biopsy. As our case demonstrated, histological findings varied with the site of intestinal segments. Therefore, multiple endoscopic biopsies are recommended to exclude the possibility of hidden intestinal lymphoma associated with amyloidosis.

The amyloid had the typical microscopic appearance of extracellular sheets or large masses of eosinophilic, amorphous, hyaline substance. This substance was Congo red-positive. However, we did not perform anti-amyloid A or P component antibody for the AA or AL subtype.

On the basis of the above clinicopathologic findings, we are unable to explain the presence of amyloid in this case. It has been suggested that intense, prolonged antigenic stimulation can lead to marked plasma cell differentiation with abnormal immunoglobulin production and amyloid deposition. However, this hypothesis does not fully explain our findings, because plasmacytic differentiation was not prominent in this case.

The diagnosis of marginal zone B-cell lymphoma may be excluded, because marginal zone B-cell lymphoma is rare in the small intestine. In addition, amyloidosis and monoclonal gammopathy is very rare in this subtype. Other low grade B-cell lymphoma should be included in the differential diagnoses. The diagnosis of marginal zone B-cell lymphoma is based on both morphological and immunophenotypic findings.

In conclusion, we report the first case of marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of MALT in the small intestine associated with amyloidosis in Korea. This unusual association should be borne in mind when diagnosing gastrointestinal tract amyloidosis, especially with endoscopic biopsy.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Histologic features of a resection specimen of small intestine. (A) The intestinal wall was thickened by a double process. Here, amorphous acidophilic material in the submucosa and intestinal wall were mixed with lymphoid infiltrate (H&E, scanning view). (B) High power view (H&E, × 40) and apple-green bi-refringence under polarized light is seen Congo-red staining of amyloid (inset). (C) Diffuse proliferative lymphoid infiltrate through the intestinal wall up to the serosa (H&E, scanning view). (D) The lymphoid infiltrate was composed mainly of small lymphoid cells (H&E, × 400). |

| Fig. 2Histologic features of mesenteric lymph node biopsy. Amyloid deposits are dense admixed with some aggregates of lymphoid cells. Islands of lymphoid infiltration are composed of small lymphoid cells, some of which show plasmacytic differentiation (H&E, scanning view and × 100-inset). |

References

1. Briggs GW. Amyloidosis. Ann Intern Med. 1961. 55:943–957.

2. Legge DA, Carlson HC, Wollaeger EE. Roentgenologic appearance of systemic amyloidosis involving gastrointestinal tract. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1970. 110:406–412.

3. Baldewijns M, Ectors N, Verbeeck G, Janssens J, De Schepper J, Ponette E, Geboes K, Desmet V. Intermittent subobstruction and cholestasis as complications of duodenal amyloid tumours. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1995. 19:218–221.

4. Hamaya K, Kitamura M, Doi K. Primary amyloid tumors of the jejunum producing intestinal obstruction. Acta Pathol Jpn. 1989. 39:207–211.

5. Hauben E, Fierens H, Heylen H, Van Marck E. Localized amyloid tumour of the duodenum: a case report. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 1997. 60:304–305.

6. Peny MO, Debongnie JC, Haot J, Van Gossum A. Localized amyloid tumor in small bowel. Dig Dis Sci. 2000. 45:1850–1853.

7. Arista Nasr J, Lome-Maldonado C. Diffuse small lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma of the GI tract associated with massive intestinal amyloidosis. Rev Invest Clin. 1993. 45:71–75.

8. Caulet S, Robert I, Bardaxoglou E, Noret P, Tas P, Le Prise Y, Launois B, Ramee MP. Malignant lymphoma of mucosa associated lymphoid tissue: a new etiology of amyloidosis. Pathol Res Pract. 1995. 191:1203–1207.

9. Das K, Ghoshal UC, Jain M, Rastogi A, Tiwari S, Pandey R. Primary gastric lymphoma and Helicobacter pylori infection with gastric amyloidosis. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2005. 24:220–222.

10. Goteri G, Ranaldi R, Pileri SA, Bearzi I. Localized amyloidosis and gastrointestinal lymphoma: a rare association. Histopathology. 1998. 32:348–355.

11. Ranaldi R, Goteri G, Santinelli A, Rezai B, Pileri S, Poggi S, Bearzi I. Centrocytic-like lymphoma associated with localized amyloidosis of the large intestine. Virchows Arch. 1994. 425:327–330.

12. Wright JR, Calkins E, Humphrey RL. Potassium permanganate reaction in amyloidosis. A histologic method to assist in differentiating forms of this disease. Lab Invest. 1977. 36:274–281.

13. Kim SY, Bang BK, Park CW, Kim KW, Yun SR, Han CM, Park YH, Ahn SJ, Park SY, Kim HJ, Suh KS, Park KK. An unusual case of AA type amyloidosis in lymphoma. Korean J Nephrol. 1999. 18:808–814.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download