Abstract

Heart transplantation is a standard treatment for end-stage heart disease. Pediatric heart transplantation, however, is not frequently performed due to the shortage of pediatric heart donors. This is the first report of pediatric heart transplantation in Korea. Our retrospective study included 37 patients younger than 18 yr of age who underwent heart transplantation at Asan Medical Center between August 1997 and April 2009. Preoperative diagnosis was either cardiomyopathy (n = 29, 78.3%) or congenital heart disease (n = 8, 22.7%). Mean follow up period was 56.9 ± 44.6 months. There were no early death, but 7 late deaths (7/37, 18.9%) due to rejection after 11, 15, 41 months (n = 3), infection after 5, 8, 10 months (n = 3), suspicious ventricular arrhythmia after 50 months (n = 1). There was no significant risk factor for survival. There were 25 rejections (25/37, 67.6%); less than grade II occurred in 17 patients (17/25, 68%) and more than grade II occurred in 8 patients (8/25, 32%). Actuarial 1, 5, and 10 yr survival was 88.6%, 76.8%, and 76.8%. Our midterm survival of pediatric heart transplantation showed excellent results. We hope this result could be an encouraging message to do more pediatric heart transplantation in Korean society.

Heart transplantation is a standard surgical treatment for end-stage heart disease in both adults and children. Pediatric heart transplantation, however, is not frequently performed due to the shortage of pediatric heart donors. The total number of pediatric heart transplant procedures has remained stable for the past 15 yr at approximately 400 procedures per year and the total number of transplant centers reporting data has stabilized at approximately 80 (1). The first adult heart transplantation in Korea was performed in November, 1992 (2) and long-term results of 112 heart transplantation in a single center was reported lately (3). However, there is no report of pediatric heart transplantation until now. So we first report 12-yr experience of pediatric heart transplantation in Korea.

All patients younger than 18 yr of age who underwent heart transplantation at Asan Medical Center between August 1997 and April 2009 were included in this retrospective study: a total of 37 transplantations were reviewed for early and long-term outcomes.

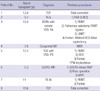

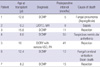

Preoperative diagnosis was either cardiomyopathy (n = 29, 78.3%) or congenital heart disease (n = 8, 21.7%). The most common diagnosis was dilated cardiomyopathy (DCMP) (n = 23, 62.2%). The median recipient age was 12.5 yr (range, 3 months to 17 yr). There were 4 children less than 5 yr, including 1 child less than 1 yr (Fig. 1). The male patients were 23 (62.2%) and the median recipient body weight was 38.7 kg (range, 3.6 to 67 kg). The median donor age was 17 yr (range, 2 to 48 yr) (Fig. 2), and the male donor patients were 23 (62.2%) and the median donor body weight was 43.5 kg (range, 14 to 73 kg) (Table 1). Sex mismatch was present in 14 cases. Male to female donor-recipient matching occurred in 7 cases whereas female to male donor-recipient matching occurred in 7 cases. The median time interval between registration and operation was 156 days (range, 0 to 877 days). Donor and recipient body weight ratio was 1.59 ± 0.9 (range, 0.67 to 4.42). The number of patients with donor and recipient body weight ratio greater than 2.5 were 3. There were no patients with renal insufficiency or hepatic failure. Surgery was all performed in bicaval technique and 8 patients with congenital heart disease (CHD) had surgical interventions before heart transplantation (Table 2).

From August 1997 to June 1999, the preoperative immunosuppressive protocol comprised induction with cyclosporine (Novartis Pharma Stein AG, Stein, Switzerland) 3-5 mg/kg and azathioprine (GlaxoSmithKline, Brentford, UK) 2-3 mg/kg per os (PO).

After June 1999, the preoperative immunosuppressive protocol comprised daclizumab (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) (anti-IL2 receptor monoclonal antibody) 1mg/kg mixed with normal saline 50 Ml intravenously (IV), replacement of azathioprine with mycophenolate mofetil (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) 500 mg PO and administration of cyclosporin 2-3 mg/kg PO. Intraoperatively, methylprednisolone (Pfizer Inc., NY, NY) 5-10 mg/kg IV was injected after aortic declamping simultaneously. Postoperatively, mycophenolate mofetil 500 mg b.i.d. PO and daclizumab were administered as scheduled to maintain the WBC count at 4,000-6,000/µL. Postoperatively, cyclosporine trough level was maintained at 300-400 ng/dL by the EMI method during the first year and 150-200 ng/mL thereafter. Methylprednisolone (Kunwha Pharmaceutical Co, Seoul, Korea) was initially given at 1 mg/kg/day and then was decreased to 0.25 mg/kg/day at 1 month and 0.1 mg/kg/day at 1 yr. For preventing chronic rejection, pravastain (CJ Pharma, Seoul, Korea) 5 mg PO was started and then 10 mg PO was maintained. To evaluate rejection, endomyocardial biopsy, echocardiography, EKG, and chest radopgraph were performed at postoperatively 2 weeks, 4 weeks, 2 months, 3 months, 6 months, 12 months and then every 6 months. In case of rejection, methylprednisolone 10 mg/kg IV pulse therapy for 3 days was started and then methylprednisolone 1 mg/kg PO was started and then tapered as usual amount.

As previously reported (3), preoperatively, hepatitis B virus vaccination was carried out if HBsAg was (-) and HBsAb was (-). Pneumococcal vaccination was also routinely done along with postoperative sulfamethoxazole and trimethoprim (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) administration throughout the first year if tolerable. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) prophylaxis with ganciclovir (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) IV was carried out for 4 weeks if the recipient CMV was IgG (+). If the recipient CMV was IgG (-) but the donor CMV was IgG (+), IV ganciclovir was given for 4 weeks and then switched to oral ganciclovir for another 2-3 months.

Routine follow-up examination for detection of acute or chronic rejection, endomyocardial biopsy, echocardiography, EKG, and chest radiopgraph were performed according to the schedule as mentioned above. Evaluation of graft vascular disease (GVD) was performed by coronary angiogram and intravascular ultrasonography at postoperatively 2 weeks, and 12 months. Hypertension and hypercholesteremia were treated with angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, calcium antagonists, and HMG CoA reductase inhibitor to prevent graft vessel disease.

All data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation or median value. Long-term survival was derived by the Kaplan-Meier method with significance determined by log-rank analysis. All statistics were calculated using SPSS 17.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The level of significance was set at P < 0.05.

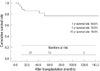

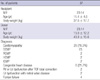

The mean and median follow up period were 56.9 ± 44.6 and 44.8 months (5.2 to 144.8 months). The mean ischemic time was 149 ± 61.4 min. There were no early deaths, but seven late deaths occurred (7/37, 18.9%), three from rejection after 11, 15, and 41 months; one from fungal pneumonia after 5 months; one caused by sepsis after 8 months; one from a fungal cerebral embolism after 10 months; and one from suspicious ventricular arrhythmia after 50 months who had a syncope at the school, without documented arrhythmia at another hospital. The patient suddenly died while she was being transferred to our center (Table 3). The actuarial 1-, 5-, and 10-yr survival rates were 88.6%, 76.8%, and 76.8%, respectively (Fig. 3). In one case, neurologic complication was occurred. This 12-yr-old patient (patient No. 5, Table 2) had a permanent pacemaker after the Fontan operation. He suddenly suffered a sudden cardiac arrest due to ventricular fibrillation and received cardiopulmonary cerebral resuscitation. He underwent heart transplantation without pre-transplant neurologic assessments. After the transplantation, we found that he had a hypoxic brain damage. He is now bed-ridden state.

During the waiting period for heart transplantation, 16 patients (16/37, 43.3%) were hospitalized with inotropic support and 5 patients (5/37, 13.5%) were treated with ventilator support. There were 3 cases supported by extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO); of them 2 cases as a bridge to transplantation and 1 case as postoperative support.

The first 3-month-old patient with left ventricular outflow tract obstruction, mitral regurgitation, left ventricular (LV) dysfunction underwent corrective repair, but the baby was treated with EMCO due to low cardiac output and had been on 30 days of ECMO, he underwent transplantation and ECMO was weaned successfully in postoperative 7 days. And the second 13-yr-old patient with intramural coronary repair had a late LV dysfunction and was treated with ECMO for 14 days. He underwent heart transplantation and ECMO was weaned successfully in the operating room. One patient with dilated cardiomyopathy (DCMP) was treated with ECMO immediate post-transplantation due to high pulmonary artery pressure (PAP), but the weaning was successfully performed in postoperative 1 day.

We analyzed survival with risk factors including younger age less than 1 yr or 5 yr old, preoperative ventilatory support, preoperative inotropic support, creatinine level, bilirubin level, preoperative ECMO support, ischemic time, congenital heart disease, previous cardiac surgery, donor sex and recipient sex. There was no significant risk factor for survival.

There were 25 rejections (25/37, 67.6%). Of these rejections less than grade II occurred in 17 patients (17/25, 68%) and rejections more than grade II occurred in 8 patients (8/25, 32%) (4). The patients with rejections more than grade II were treated methylprednisolone pulse therapy. Postoperatively, there were 23 hypertension (23/37, 62.2%), 4 renal dysfunction (4/37, 10.8%), 4 hyperlipidemia (4/37, 10.8%), 1 diabetes mellitus (1/37, 2.7%), 2 coronary vasculopathy (2/37, 5.4%).

Heart transplantation has been recently accepted as a standard treatment for infants and children with end-stage cardiomyopathy or complex congenital heart disease. The overall post-transplantation survival rate of these patients, from birth to 18 yr of age, is excellent (> 65% at 5 yr), comparable with the overall survival rate of adult transplant recipients. The overall 5- and 9-yr post-transplantation survival rates of pediatric heart recipients are approximately 65% and 60%, respectively (5). In this study, the actuarial 5- and 10-yr survival was 76.8%, which is higher than previously reported (1, 5, 6).

In the past 15 yr, almost 400 pediatric heart transplantations per year have been performed worldwide, and about 100 per year involve infant recipients (1). Pediatric transplant recipients differ from adults with respect to indications, evaluation, surgical technique, and post-transplantation management (5).

The major difference between adult and pediatric recipients lies in the indications for transplantation. In adults, the main indications are equally divided between cardiomyopathies and coronary artery disease, with a minority of patients presenting with congenital heart disease. In comparison, the main indication for transplantation in children younger than 1 yr of age is congenital heart disease (> 75%), primarily involving hypoplastic left heart syndrome (7). In the 1- to 10-yr age group, more than 50% of patients have cardiomyopathy and approximately 37% have CHD; in adolescents, 11 to 17 yr of age, the main indication is cardiomyopathy in 64% and CHD in 26% (6). In this study, we had 1 case of CHD (1/1, 100%) younger than 1 yr, 3 cases of CHD (3/11, 27.3%) in the 1- to 10-yr age group and 4 cases of CHD in adolescents (4/25, 16%). Our data showed that number of recipient with CHD were decreasing as patients age getting older like other studies. Also, we had only 1 infant and no hypoplastic left heart syndrome case for which transplantation could be needed mostly. This might be due to the age limitation more than 2 month old to be a donor by the National Assembly of the Republic of Korea (8).

For successful treatment, or at least to improve the probability of success and to reduce the risks of morbidity and mortality of transplantation, timely referral is essential. Although this applies to all pediatric patients, regardless of diagnosis, this is especially applicable to patients with CHD and end-stage cardiac failure because options for support are limited (5).

Griffiths and colleagues (9) studied 34 Fontan patients who were treated with heart transplantation. They divided failing Fontan patients as two groups: impaired ventricular function (IVF) and those with preserved ventricular function (PVF) but with failing Fontan physiology (protein-losing enteropathy and plastic bronchitis). They found PVF group with failing Fontan physiology had a lower survival rates than IVF group after transplantation and suggested necessity to improve the management and timing for transplantation amongst this group. Our series also included four patients with functional single ventricle, including one with a bidirectional cavopulmonary shunt (BCS) and three with failing Fontan. All of these patients had impaired ventricular function before transplantation and 1 patient died of rejection after 41 months. Based on the study of Griffiths et al., we should pay special attention to the failing Fontan physiology group with preserved ventricular function, not to miss the adequate timing for transplantation.

Children with CHD referred for transplantation have often undergone several palliative surgical procedures, which increase post-transplantation surgical risks (5). Moreover, because of the limited number of donors, size-mismatched pediatric cardiac transplantation is common. Heart transplantation of oversized grafts is more difficult because of insufficient exposure, and lack of space of launching of donor heart. However, Razzouk et al. (10) reported that post-transplant morbidity and survival are not adversely influenced by the oversized heart. They also reported that whenever compression of the graft is a concern, the sternum is left open for a few days. We also had 2 cases of opened sternum, 1 patient with donor-recipient weight ratio 4.2, the other with 4.4. The last patient underwent delayed sternal closure after 5 months as already reported (11).

Another concern with the use of large heart grafts has been the 'big-heart or hyperperfusion syndrome' (12). A strong, large donor heart may generate a high systemic pressure and excessive cardiac output in the recipient who has previously endured a low-flow state. Such an acute rise in cerebral blood flow can cause reactive vasoconstriction and precipitate convulsions or coma. The danger of this syndrome is generally limited to the first few post-operative days. Soon after transplantation, the graft stroke volume is adjusted according to the recipient's needs, and not to the donor's requirements (13). We had 3 cases with donor-recipient weight ratio over than 2.5, but no cases showed big-heart syndrome.

Management for growing children after transplantation is clearly different from adults. Most adult transplant recipients tolerate fairly uniform medication regimens and monitoring, but children's drug metabolism varies significantly with age. Successful management for children lies not only in proper medical treatment but also in considering for their growth and development, especially adolescence period mood change (5).

At present, we do not have psychological support programs which help the children and their families comply with long-term medications after transplantation. We are planning to make a team, including consulting psychologists, social workers, surgeons, cardiologists, and transplant nurse coordinators who frequently contact with the patients and families.

According to tenth official pediatric heart transplantation report - 2007 (1), CHD with younger than 1 yr, preoperative ECMO support, retransplant, preoperative ventilatory support or hospitalization, donor age, creatinine, weight ratio, pediatric center transplant volume and bilirubin, female recipient and female donor were risk factors for mortality.

In this study, we had 8 cases with CHD, 2 of them needed preoperative ECMO support. One 3 months old baby with complex CHD needed preoperative ECMO support for 30 days died 6 months later. The other 13-yr-old patient with congenital intramural coronary artery needed preoperative ECMO support has been still alive. Both CHD and preoperative ECMO was not statistically significant risk factor. Preoperative ventilatory support was applied in 5 patients with one mortality. Preoperative in hospital care was needed in 16 cases with 3 mortalities. Also, these two factor were not significant risk factor. Overall, we could not find any significant risk factor in mortality. This result might be partly due to the small number of our patients especially those of neonates and infants.

In summary, our midterm results of pediatric heart transplantation are excellent. We hope this result could be an encouraging message to do more pediatric heart transplantation in Korean society.

Figures and Tables

Table 2

Representative previous surgeries of pediatric patients with congenital heart

disease

TOF, tetralogy of Fallot; TA, tricuspid atresia; PAB, pulmonary artery banding; BCS, bidirectional cavopulmonary shunt; DORV, double outlet right ventricle; PA, pulmonary atresia; RMBT, right modified Blalock-Taussig shunt; LMBT, left modified Blalock-Taussig shunt; PPM, permanent pacemaker; LVOTO, left ventricular outflow tract obstruction; MR, mitral regurgitation; MVR, mitral valve replacement; TGA, transposition of the great arteries; VSD, ventricular septal defects; PS, pulmonary stenosis; MVP, mitral valvuloplasty.

AUTHOR SUMMARY

Heart Transplantation in Pediatric Patients: Twelve-Year Experience of the Asan Medical Center

Hong Ju Shin, Won Kyoung Jhang, Jeong-Jun Park, Tae Jin Yun, Young Hwee Kim, Jae Joong Kim, Meong-Gun Song, and Dong Man Seo

Although heart transplantation is a standard treatment for end-stage heart disease, pediatric heart transplantation is not frequently performed due to the shortage of donors. Here we analyzed the cases of 37 young patients (< 18 yr) who underwent heart transplantation between August 1997 and April 2009 in Asan Medical Center. Preoperative diagnosis was either cardiomyopathy (n = 29) or congenital heart disease (n = 8). Mean follow-up period was 56.9 ± 44.6 months. There were no early death, but 7 late deaths (18.9%) due to rejection (n = 3), infection (n = 3), and ventricular arrhythmia (n = 1). There was no significant risk factor for the post-operative death. Among the 25 rejections (67.6%), cases more severe than grade II occurred in 8 patients (32%). Actuarial 1, 5, and 10 yr survival was 88.6%, 76.8%, and 76.8%, respectively. As a whole, the midterm survival of pediatric heart transplantation showed hopeful results in Asan Medical Center.

References

1. Boucek MM, Aurora P, Edwards LB, Taylor DO, Trulock EP, Christie J, Dobbels F, Rahmel AO, Keck BM, Hertz MI. The registry of the international society for heart and lung transplantation: tenth official pediatric heart transplantation report - 2007. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2007. 26:796–807.

2. Song MG, Seo DM, Lee JW, Kim JJ, Park SW, Song JK, Song JH, Cho MW, Kim KY, Kim DW, Min WK, Lee I, Lee JK, Sohn KH. Cardiac transplantation; 1 case report. Korean J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1993. 26:224–227.

3. Choo SJ, Kim JJ, Kim SP, Lee JW, Wan RS, Park NH, Lee SK, Yoo DG, Lee JW, Song H, Chung CH, Kim KS, Song MG. Heart transplantation. A retrospective analysis of the long-term results. Yonsei Med J. 2004. 45:1173–1180.

4. Billingham ME, Cary NR, Hammond ME, Kemnitz J, Marboe C, McCallister HA, Snovar DC, Winters GL, Zerbe A. A working formulation for the standardization of nomenclature in the diagnosis of heart and lung rejection: Heart Rejection Study Group. The International Society for Heart Transplantation. J Heart Transplant. 1990. 9:587–593.

5. Kichuk-Chrisant MR. Children are not small adults: some differences between pediatric and adult cardiac transplantation. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2002. 17:152–159.

6. Boucek MM, Edwards LB, Keck BM, Trulock EP, Taylor DO, Mohacsi PJ, Hertz MI. The registry of the international society for heart and lung transplantation: fifth official pediatric report-2001 to 2002. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2002. 21:827–840.

7. Odim J, Laks H, Burch C, Komanapalli C, Alejos JC. Transplantation for congenital heart disease. Adv Card Surg. 2000. 12:59–76.

8. Organ Donation and Transplantation Law 16-2. The National Assembly of the Republic of Korea. accessed on 23 Feb 23 2009. Available at: htp://likms.assembly.go.kr/law/jsp/Law.jsp?WORK_TYPE=LAW_BON&LAW_ID=A1660&PROM_NO=08852&PROM_DT=20080229&HanChk=Y.

9. Griffiths ER, Kaza AK, Wyler von Ballmoos MC, Loyola H, Valente AM, Blume ED, del Nido P. Evaluating failing Fontans for heart transplantation: predictors of death. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009. 88:558–564.

10. Razzouk AJ, Johnston JK, Larsen RL, Chinnock RE, Fitts JA, Bailey LL. Effect of oversizing cardiac allografts on survival in pediatric patients with congenital heart disease. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2005. 24:195–199.

11. Cho HJ, Seo DM, Jhang WK, Park CS, Kim YH. Transplantation of an extremely oversized heart after prolonged extracorporeal membrane oxygenation assistance in a 3-month-old infant with congenital heart disease. Korean J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009. 42:630–634.

12. Reichart B. Size matching in heart transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1992. 11(4 Pt 2):S199–S202.

13. Kertesz NJ, Gajarski RJ, Towbin JA, Geva T. Effect of donor-recipient size mismatch on left ventricular remodeling after pediatric orthotopic heart transplantation. Am J Cardiol. 1995. 76:1167–1172.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download