Abstract

The purpose of this study was to establish a prediction rule for severe illness in adult patients hospitalized with pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009. At the time of initial presentation, the baseline characteristics of those with severe illness (i.e., admission to intensive care unit, mechanical ventilation, or death) were compared to those of patients with non-severe illnesses. A total of 709 adults hospitalized with pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 were included: 75 severe and 634 non-severe cases. The multivariate analysis demonstrated that altered mental status, hypoxia (PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 250), bilateral lung infiltration, and old age (≥ 65 yr) were independent risk factors for severe cases (all P < 0.001). The area under the ROC curve (0.834 [95% CI, 0.778-0.890]) of the number of risk factors were not significantly different with that of APACHE II score (0.840 [95% CI, 0.790-0.891]) (P = 0.496). The presence of ≥ 2 risk factors had a higher sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value and negative predictive value than an APACHE II score of ≥ 13. As a prediction rule, the presence of ≥ 2 these risk factors is a powerful and easy-to-use predictor of the severity in adult patients hospitalized with pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009.

While most pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 infections were mild or subclinical, early reports suggested that clinical courses of pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 were somewhat different from that of seasonal influenza (1, 2). Although individuals with comorbid conditions were at high risk, small subsets of previously healthy people developed rapidly progressive disease. In severe cases, patients generally began to deteriorate 3-5 days after the onset of symptom, with rapid progression to respiratory failure within 24 hr. Most of these required immediate life support with mechanical ventilation, renal replacement therapy, or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

Although most studies have evaluated risk factors for mortality (3-5), a few have focused on those associated with severe pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 (6, 7). From the viewpoint of clinical practice, knowledge on risk factors for the severity including the mortality and the prediction of severe cases is more crucial for decisions regarding hospitalization, treatment, or intensive care of these patients. Therefore, we evaluated the baseline characteristics of adult patients hospitalized with pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 to identify risk factors associated with severity. Eventually, a rule comprising these risk factors was established to predict the severity of illness in adult patients hospitalized with pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009.

This study was conducted at 17 teaching hospitals in Korea: Kangwon National University Hospital, Chuncheon; Gyeongsang National University Hospital, Jinju; Kwandong University Myongji Hospital, Goyang; Dongguk University Ilsan Hospital, Goyang; Boramae Medical Center, Seoul; Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seongnam; Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul; Pusan National University Yangsan Hospital, Yangsan; Wonju Christian Hospital, Wonju; Yeungnam University Medical Center, Daegu; Wonkwang University Hospital, Iksan; Inje University Sanggye-Paik Hospital, Seoul; Inje University Ilsan-Paik Hospital, Goyang; National Health Insurance Corporation Ilsan Hospital, Goyang; Chunbuk National University Hospital, Jeonju; Cheongju St. Mary's Hospital, Cheongju; and Kangbuk Samsung Hospital, Seoul.

All adult patients hospitalized with the laboratory-confirmed, pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 from September 1, 2009 to February 28, 2010 were included in the study. Laboratory-confirmed cases were defined as the presence of influenza-like illness with pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus infection confirmed by real-time or multiplex reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction assays. Patients younger than 18 yr were excluded.

Demographic, clinical, laboratory and radiographic data were collected from all patients. Obesity was defined as a body mass index (BMI) of more than 25 kg/m2. Comorbid conditions included chronic lung diseases (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, pneumoconiosis, or bronchopulmonary dysplasia), cardiovascular diseases (congestive heart failure, ischemic heart disease, or cyanotic congenital heart disease), cerebrovascular diseases (stroke or cerebral hemorrhage), malignancy, immunosuppression (HIV infection, asplenia or hyposplenia, transplantation, anticancer chemotherapy, corticosteroid, or other immunosuppressants), diabetes mellitus, chronic renal diseases (nephrotic syndrome or chronic renal failure), chronic liver diseases (liver cirrhosis or chronic active hepatitis), and neurocognitive diseases (mental retardation, dementia, or seizure).

To identify risk factor(s) associated with severe pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 at the time of initial presentation, we compared the baseline characteristics of patients with severe illness to those of patients with non-severe illness. Severe cases were defined as those who had been admitted to intensive care unit (ICU), mechanically ventilated, or died of influenza itself or related complications; other cases were considered to have a non-severe illness. Clinical or laboratory parameters derived from Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI) for community-acquired pneumonia or the diagnostic criteria for sepsis or severe sepsis were used in part to evaluate the baseline characteristics of patients (8, 9). The presence of the following complications due to infection was also determined: pneumonia (defined as new or progressive infiltrate(s) on chest radiography), acute respiratory distress syndrome (PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 200 in the presence of bilateral alveolar infiltrates in chest radiography), septic shock (systolic blood pressure < 90 mm Hg despite adequate fluid resuscitation), acute renal failure (serum creatinine ≥ 2.0 mg/dL without previous renal disease), rhabdomyolysis (profound muscle weakness and tenderness, brown-colored urine, and CPK ≥ 5 times the upper normal limit), and exacerbation of underlying diseases (worsening of the patient's condition such that additional treatment is required).

A Pearson's chi-square or Fisher's exact test was used for categorical variables, and the Student's t-test was used for continuous variables. A multivariate logistic regression analysis using baseline characteristics seen only at the time of initial presentation was performed to identify risk factors associated with severe pandemic influenza A (H1N1). A level of significance of less than 0.10 was required for inclusion and greater than 0.05 meant exclusion. The goodness-of-fit for this regression model was verified by the Hosmer-Lemeshow test (10).

As a prediction rule for severe pandemic influenza A (H1N1), both the number of risk factors, derived from the logistic regression model, and the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score were calculated for each patient. To validate their discriminatory power, the sensitivity and specificity of the risk factors were compared to those of the APACHE II score by means of the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves (11). We also determined their cut-points defining severe pandemic influenza A (H1N1) to maximize the sum of sensitivity and specificity.

A two-tailed P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant for all analyses. IBM SPSS Statistics 18 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and dBSTAT for Windows version 5.0 (dBSTAT, Seoul, Korea) were used.

A total of 709 adult patients hospitalized with the laboratory-confirmed, pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 were included in the study. There were 280 (39.5%) males and 429 (60.5%) females, and the median age was 50 yr (interquartile range [IQR], 31-66 yr). A total of 75 (10.6%) patients had severe illness: 23 were admitted to ICU but not ventilated, 35 were mechanically ventilated in the ICU, 5 were mechanically ventilated in emergency departments or general wards, and 12 died without either admission to ICU or mechanical ventilation.

The demographic, clinical, laboratory and radiographic findings of patients at the time of initial presentation are summarized in Table 1. The median age of severe cases was higher than that of non-severe cases (65 yr [IQR, 50-75 yr] vs 49 yr [IQR, 30-63 yr]; P < 0.001). The proportions of males and nursing home residents were also higher in severe cases (P = 0.01 and 0.002, respectively). Of the total, 367 (52.1%) had one or more comorbidities: 62 (82.7%) severe cases vs 305 (48.1%) non-severe cases (P < 0.001). Chronic lung disease (21.7%) was the most common comorbidity, followed by diabetes mellitus (13.6%), cardiovascular disease (9.4%), malignancy (9.4%), immunosuppression (8.4%), chronic liver disease (5.5%), and chronic renal diseases (5.0%). Of these, chronic lung disease, cardiovascular disease, and immunosuppression were more frequently observed in severe cases than in non-severe cases (P < 0.001, < 0.001, and 0.011, respectively). However, there were no significant differences in the proportions of pregnancy and obesity between severe and non-severe cases (P = 0.11 and 0.499, respectively).

While fever was the most common symptom (78.3%) at initial presentation, it was less frequent in severe than in non-severe cases (65.3% vs 79.8%; P = 0.004). On the contrary, dyspnea, purulent sputum, altered mental status, and cyanosis were more frequent in severe than in non-severe cases (P < 0.001, 0.018, < 0.001, and < 0.001, respectively). However, the median interval from symptom onset to initial presentation in severe cases was not significantly different than that in non-severe cases (2 days [IQR, 1-4 days] vs 2 days [IQR, 1-4 days]; P = 0.619). With respect to initial laboratory findings, anemia (hematocrit < 30%), azotemia (BUN ≥ 30 mg/dL), hyperglycemia (serum glucose ≥ 250 mg/dL), hyponatremia (serum sodium < 130 mEq/L), acidosis (arterial pH < 7.35), and hypoxia (PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 250) were more frequent in severe than in non-severe cases (P < 0.001, < 0.001, 0.001, < 0.001, and < 0.001, respectively). Of all patients, 262 (37.0%) had pneumonia at the time of initial presentation: 53 (70.7%) severe vs 209 (33.0%) non-severe cases (P < 0.001). Both lungs were more frequently involved in severe cases than in non-severe cases (61.3% vs 21.3%; P < 0.001).

The clinical courses of patients with pandemic influenza A (H1N1) are outlined in Table 2. Of the total, 692 (97.6%) patients were treated with one or more antiviral agents: 670 (94.5%) with oseltamivir, 19 (2.7%) with zanamivir, 1 (0.1%) with peramivir, and 2 (0.3%) with a combination of oseltamivir, amantadine, and ribavirin. There was no significant difference in antiviral regimens between severe and non-severe cases (P = 0.362). The median interval from symptom onset to initiation of antiviral therapy in the 692 treated cases was 2 days (IQR, 1-3 days); there was no significant difference between severe and non-severe cases (1 day [IQR, 1-3 days] vs 2 days [IQR, 1-3 days]; P = 0.734). However, the median duration of fever after initiation of antiviral therapy was longer in severe than in non-severe cases (2 days [IQR, 1-5 days] vs 1 day [IQR, 1-2 days]; P = 0.001). Antibacterial agent(s), vasopressor(s), corticosteroid(s), and supplementary oxygen therapy were more frequently given to severe than non-severe cases (all P < 0.001). The median length of hospital stay in all patients was 5 days (IQR, 3-9 days): 11 days (IQR, 7-25 days) in severe vs 5 days (IQR, 3-8 days) in non-severe cases (P < 0.001). Influenza-related complications were observed in 110 (15.5%) patients: 54 (72.0%) severe vs 56 (8.8%) non-severe cases (P < 0.001). Pneumonia (37.0%) was the most common complication, followed by exacerbation of underlying lung disease (8.3%), acute respiratory distress syndrome (3.9%), acute renal failure (2.4%), septic shock (1.8%), and exacerbation of underlying heart disease (1.8%).

A total of 37 severe cases died during hospitalization (in-hospital case-fatality rate, 5.2%), and nine (24.3%) of these died within 3 days of initial presentation. The median age of fatal cases was 68 yr (IQR 59-79 yr), which was higher than that of non-fatal cases (49 yr, [IQR 30-64 yr]; P < 0.001). Of the 37 fatalities, only three (8.1%) were under 65 yr of age and none had underlying comorbidities. There was no significant difference in the median interval from symptom onset to initiation of antiviral agent(s) between fatal and non-fatal cases (1 day, IQR 0-4 days) vs 2 days (IQR 1-3 days; P = 0.918). Either influenza itself or pneumonia (40.5%) was the most common cause of in-hospital death, followed by exacerbation of underlying lung disease (13.5%), exacerbation of underlying heart disease (10.8%), exacerbation of other underlying disease (18.9%), nosocomial infection (5.4%), and unknown causes (10.8%).

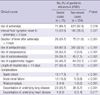

In the multivariate logistic regression model using baseline characteristics seen only at the time of initial presentation, altered mental status, hypoxia (PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 250), bilateral lung infiltration, and old age (≥ 65 yr) were independent risk factors associated with severe pandemic influenza A (H1N1) (all P < 0.001; Table 3). The Hosmer-Lemeshow test did not show statistical significance (P = 0.88), indicating the goodness of fit of this logistic regression model.

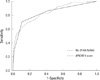

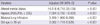

The median number of risk factors in severe cases was higher than that in non-severe cases (2, IQR 1-3, vs 0, IQR 0-1) (P < 0.001). The median APACHE II score was also higher in severe cases than in non-severe cases (17, IQR 10-22, vs 6, 3-11) (P < 0.001). Both the number of risk factors and APACHE II scores were significantly correlated with patient age (Pearson's correlation coefficients > 0.5; all P < 0.001). The ROC curve for the number of risk factors, which were derived from the logistic regression model, was compared to that for the APACHE II scores (Fig. 1). The areas under the ROC curves were 0.834 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.778-0.890) for the number of risk factors and 0.840 (95% CI, 0.790-0.891) for APACHE II score, but there was no significant difference between both areas under the ROC curves (P = 0.496). When the cut-points were determined to maximize the sum of the sensitivity and specificity by means of the ROC curves, they were 2 for the number of risk factors and 13 for the APACHE II score (Table 4). As a prediction rule for severe pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009, the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) of the number of risk factors ≥ 2 were all higher than those of the APACHE II score ≥ 13.

During an influenza A (H1N1) 2009 pandemic, the determination of the severity of illness played an important role in early detection and proper management of severe cases and, eventually, improvement of clinical outcome. Although many studies about risk factors for death in patients with pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 has been published, no prediction rule for the severe case has yet been established. In this study, the number of risk factors (i.e., altered mental status, hypoxia, bilateral lung infiltration, and old age) as a prediction rule seems to be adequate for the detection of severe cases among adult patients hospitalized with pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009. While APACHE II has been widely used to measure the severity of illness in critically ill patients, its application to all patients with pandemic influenza A (H1N1) can be limited in clinical practice because of the complexity of its parameters. When the cut-points were determined to maximize the sum of the sensitivity and specificity, the area under the ROC curve of the number of risk factors was comparable with that of the APACHE II score. More precisely, the presence of ≥ 2 risk factors had a higher sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV than an APACHE II score ≥ 13. Therefore, we think that the presence of ≥ 2 risk factors is a more useful predictor for severe pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009, especially during a pandemic when the burden of care for the patients is too heavy for the physicians.

This study also highlights several clinical features observed in adult patients hospitalized with severe pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 infection. Early case reports indicated that the infection in previously healthy young individuals might often be associated with serious complications or death (4, 12). Most of the serious illnesses occurred among children and young adults, and approximately 90% of deaths were observed in those < 65 yr of age. However, the overall case fatality rate among hospitalized patients appeared to be highest among those ≥ 50 yr of age. In this study, which included only adult patients hospitalized with pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009, there was a tendency for the severity of illness to increase with patient age. Most deaths occurred in patients who were ≥ 65 yr of age or had one or more comorbidities, but the only death attributed directly to influenza occurred in a previously healthy young individual. Although determination of the true case-fatality rate of pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 is particularly challenging, it is thought to be less than 0.5%, with a broad range of estimates (13, 14). In a surveillance data (15), a total of 740,835 patients were reported to be infected with pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 and 225 of them were reported to have died during 2009-2010 influenza season. The incidence was calculated as 1,493 per 100,000 population and the case fatality rate was 30 per 100,000 cases. In an early report (16) that included 272 patients hospitalized with pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009, the in-hospital case-fatality rate was -7%; it was -5% in the present study.

Previous studies have suggested that pregnant women are at increased risk for complication and death from pandemic influenza A (H1N1) infection, and that this risk is highest in the third trimester (17-19). In a cohort study (20), however, there was no death among 211 pregnant women, suggesting that the prevention of disease progression with early treatment might account for the cohort of mild cases. In the present study, pregnancy itself was not significantly associated with complications (spontaneous abortion, preterm labor, or fetal distress), the severity of illness, or death. This may be attributable to the small number of pregnant women as well as the early treatment with antiviral agent(s) in this study.

Several studies have suggested that fever is one of the most common symptoms (> 80%) at initial presentation (12, 21). In this study, approximately 80% of all hospitalized patients presented initially with fever; however, more than one-third of patients with severe illness had no fever at initial presentation, regardless of use of antipyretic agent(s). This finding suggests that pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 should not be excluded in patients with severe influenza-like illness, even if they have neither fever nor a history of fever. Furthermore, a confirmatory test for pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 may be necessary in such patients.

In recent studies (6, 7, 21), the presence of one or more comorbidities was found to be associated with both admission to ICU and death in patients with pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009. Comorbidities associated with complications of seasonal influenza are also risk factors for complications related to this virus. Although chronic lung disease, cardiovascular disease, and immunosuppression were more frequently detected in severe than in non-severe cases in the bivariate analysis of this study, they were not found to be independent risk factors for severe illness in the multivariate logistic regression analysis. Instead, the multivariate logistic regression analysis demonstrated that altered mental status, hypoxia, bilateral lung infiltration, and old age were independent risk factors for severe illness in adult patients hospitalized with pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009.

The use of neuraminidase inhibitor within 48 hr of symptom onset may reduce the risk of progression to severe illness or death (16, 21, 22). In an early report (23), the use of neuraminidase inhibitor even 48 hr after symptom onset was associated with reduced rates of death. In this study, however, more than 70% of infected patients received neuraminidase inhibitor within 48 hr after symptom onset, so that their clinical outcome was not related with the timing of antiviral administration.

The strengths of this study include it being a nationwide multicenter study with a large number of laboratory-confirmed cases, relatively little missing data, careful control of confounding factors in the analyses, and the establishment of a prediction rule for severe pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 with large sample size (e.g., the number of events per each variable ≥ 40). This study has several limitations. Because only adult patients hospitalized with pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 were included in this study, the derived prediction rule cannot be applied to estimate the severity of illness in children or adult outpatients. In addition, final outcome was measured as in-hospital mortality because many of the patients were lost to follow-up. Finally, a prediction rule derived from this study need be externally validated in other larger-scaled studies for testing accuracy and generalizability and studying the clinical impact of a rule on physician's behavior and patient's outcome (24).

In summary, although clinical features of adult patients hospitalized with pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 can be diverse, altered mental status, hypoxia, bilateral lung infiltration, and old age are independent risk factors for severe illness. As a prediction rule, furthermore, the presence of ≥ 2 of these risk factors can be used to determine the likely severity of illness.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for the number of risk factors and APACHE II score. The areas under the ROC curves are 0.834 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.778-0.890) for the number of risk factors and 0.840 (95% CI, 0.790-0.891) for the APACHE II score (P = 0.496 for each pairwise comparison).

Table 1

Baseline characteristics of adults hospitalized with pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 (N = 709)

Table 3

Multivariate analysis of risk factors associated with severity at initial presentation (N = 709)

AUTHOR SUMMARY

A Prediction Rule to Identify Severe Cases among Adult Patients Hospitalized with Pandemic Influenza A (H1N1) 2009

Won Sup Oh, Seung-Joon Lee, Chang-Seop Lee, Ji-An Hur, Ae-Chung Hur, Yoon Seon Park, Sang-Taek Heo, In-Gyu Pai, Sang Won Park, Eu Suk Kim, Hong Bin Kim, Kyoung-Ho Song, Kkot Sil Lee, Sang-Rok Lee, Joon Sup Yeom, Su Jin Lee, Baek-Nam Kim, Yee Gyun g Kwak, Jae Hoon Lee, Yong Keun Kim, Hyo Youl Kim, Nam Joong Kim, and Myoung-don Oh

During a pandemic, it is important to establish a prediction rule for detecting severe cases among patients with pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009. Data from this study showed that altered mental status, hypoxia (PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 250), bilateral lung infiltration, and old age (≥ 65 yr) were independent risk factors for severe cases among patients with pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009. For detecting severe cases, the presence of ≥ 2 risk factors had a higher sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value and negative predictive value than an APACHE II score of ≥ 13. As a prediction rule, the presence of ≥ 2 these risk factors can be easily used to determine the severity in adult patients hospitalized with pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009.

References

1. Novel Swine-Origin Influenza A (H1N1) Virus Investigation Team. Dawood FS, Jain S, Finelli L, Shaw MW, Lindstrom S, Garten RJ, Gubareva LV, Xu X, Bridges CB, Uyeki TM. Emergence of a novel swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) virus in humans. N Engl J Med. 2009. 360:2605–2615.

2. Clinical features of severe cases of pandemic influenza. World Health Organization. accessed on 10 Mar 2010. Available at http://www.who.int/csr/disease/swineflu/notes/h1n1_clinical_features_20091016/en/print.html.

3. ANZIC Influenza Investigators. Webb SA, Pettilä V, Seppelt I, Bellomo R, Bailey M, Cooper DJ, Cretikos M, Davies AR, Finfer S, Harrigan PW, Hart GK, Howe B, Iredell JR, McArthur C, Mitchell I, Morrison S, Nichol AD, Paterson DL, Peake S, Richards B, Stephens D, Turner A, Yung M. Critical care services and 2009 H1N1 influenza in Australia and New Zealand. N Engl J Med. 2009. 361:1925–1934.

4. Kumar A, Zarychanski R, Pinto R, Cook DJ, Marshall J, Lacroix J, Stelfox T, Bagshaw S, Choong K, Lamontagne F, Turgeon AF, Lapinsky S, Ahern SP, Smith O, Siddiqui F, Jouvet P, Khwaja K, McIntyre L, Menon K, Hutchison J, Hornstein D, Joffe A, Lauzier F, Singh J, Karachi T, Wiebe K, Olafson K, Ramsey C, Sharma S, Dodek P, Meade M, Hall R, Fowler RA. Canadian Critical Care Trials Group H1N1 Collaborative. Critically ill patients with 2009 influenza A (H1N1) infection in Canada. JAMA. 2009. 302:1872–1879.

5. Echevarría-Zuno S, Mejía-Aranguré JM, Mar-Obeso AJ, Grajales-Muñiz C, Robles-Pérez E, González-León M, Ortega-Alvarez MC, Gonzalez-Bonilla C, Rascón-Pacheco RA, Borja-Aburto VH. Infection and death from influenza A H1N1 virus in Mexico: a retrospective analysis. Lancet. 2009. 374:2072–2079.

6. Campbell A, Rodin R, Kropp R, Mao Y, Hong Z, Vachon J, Spika J, Pelletier L. Risk of severe outcomes among patients admitted to hospital with pandemic (H1N1) influenza. CMAJ. 2010. 182:349–355.

7. Subramony H, Lai FY, Ang LW, Cutter JL, Lim PL, James L. An epidemiological study of 1348 cases of pandemic H1N1 influenza admitted to Singapore Hospitals from July to September 2009. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2010. 39:283–288.

8. Fine MJ, Auble TE, Yealy DM, Hanusa BH, Weissfeld LA, Singer DE, Coley CM, Marrie TJ, Kapoor WN. A prediction rule to identify low-risk patients with community-acquired pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 1997. 336:243–250.

9. Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Carlet JM, Bion J, Parker MM, Jaeschke R, Reinhart K, Angus DC, Brun-Buisson C, Beale R, Calandra T, Dhainaut JF, Gerlach H, Harvey M, Marini JJ, Marshall J, Ranieri M, Ramsay G, Sevransky J, Thompson BT, Townsend S, Vender JS, Zimmerman JL, Vincent JL. International Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines Committee. American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. American College of Chest Physicians. American College of Emergency Physicians. Canadian Critical Care Society. European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. European Respiratory Society. International Sepsis Forum. Japanese Association for Acute Medicine. Japanese Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Society of Critical Care Medicine. Society of Hospital Medicine. Surgical Infection Society. World Federation of Societies of Intensive and Critical Care Medicine. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2008. Crit Care Med. 2008. 36:296–327.

10. Hosmer DW, Hosmer T, Le Cessie S, Lemeshow S. A comparison of goodness-of-fit tests for the logistic regression model. Stat Med. 1997. 16:965–980.

11. Hanley JA, McNeil BJ. A method of comparing the areas under receiver operating characteristic curves derived from the same cases. Radiology. 1983. 148:839–843.

12. Perez-Padilla R, de la Rosa-Zamboni D, Ponce de Leon S, Hernandez M, Quiñones-Falconi F, Bautista E, Ramirez-Venegas A, Rojas-Serrano J, Ormsby CE, Corrales A, Higuera A, Mondragon E, Cordova-Villalobos JA. INER Working Group on Influenza. Pneumonia and respiratory failure from swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) in Mexico. N Engl J Med. 2009. 361:680–689.

13. Nguyen-Van-Tam JS, Openshaw PJ, Hashim A, Gadd EM, Lim WS, Semple MG, Read RC, Taylor BL, Brett SJ, McMenamin J, Enstone JE, Armstrong C, Nicholson KG. Influenza Clinical Information Network (FLU-CIN). Risk factors for hospitalization and poor outcome with pandemic A/H1N1 influenza: United Kingdom first wave (May-September 2009). Thorax. 2010. 65:645–651.

14. Garske T, Legrand J, Donnelly CA, Ward H, Cauchemez S, Fraser C, Ferguson NM, Ghani AC. Assessing the severity of the novel influenza A/H1N1 pandemic. BMJ. 2009. 339:b2840.

15. Kim JH, Yoo HS, Lee JS, Lee EG, Park HK, Sung YH, Kim S, Kim HS, Shin SY, Lee JK. The spread of pandemic H1N1 2009 by age and region and the comparison among monitoring tools. J Korean Med Sci. 2010. 25:1109–1112.

16. Jain S, Kamimoto L, Bramley AM, Schmitz AM, Benoit SR, Louie J, Sugerman DE, Druckenmiller JK, Ritger KA, Chugh R, Jasuja S, Deutscher M, Chen S, Walker JD, Duchin JS, Lett S, Soliva S, Wells EV, Swerdlow D, Uyeki TM, Fiore AE, Olsen SJ, Fry AM, Bridges CB, Finelli L. 2009 Pandemic Influenza A (H1N1) Virus Hospitalizations Investigation Team. Hospitalized patients with 2009 H1N1 influenza in the United States, April-June 2009. N Engl J Med. 2009. 361:1935–1944.

17. Louie JK, Acosta M, Jamieson DJ, Honein MA. California Pandemic (H1N1) Working Group. Severe 2009 H1N1 influenza in pregnant and postpartum women in California. N Engl J Med. 2010. 362:27–35.

18. Jamieson DJ, Honein MA, Rasmussen SA, Williams JL, Swerdlow DL, Biggerstaff MS, Lindstrom S, Louie JK, Christ CM, Bohm SR, Fonseca VP, Ritger KA, Kuhles DJ, Eggers P, Bruce H, Davidson HA, Lutterloh E, Harris ML, Burke C, Cocoros N, Finelli L, MacFarlane KF, Shu B, Olsen SJ. Novel Influenza A (H1N1) Pregnancy Working Group. H1N1 2009 influenza virus infection during pregnancy in the USA. Lancet. 2009. 374:451–458.

19. World Health Organization. Transmission dynamics and impact of pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 virus. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2009. 84:481–484.

20. Lim ML, Chong CY, Tee WS, Lim WY, Chee JJ. Influenza A/H1N1 (2009) infection in pregnancy-an Asian perspective. BJOG. 2010. 117:551–556.

21. Cao B, Li XW, Mao Y, Wang J, Lu HZ, Chen YS, Liang ZA, Liang L, Zhang SJ, Zhang B, Gu L, Lu LH, Wang DY, Wang C. National Influenza A Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 Clinical Investigation Group of China. Clinical features of the initial cases of 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus infection in China. N Engl J Med. 2009. 361:2507–2517.

22. Libster R, Bugna J, Coviello S, Hijano DR, Dunaiewsky M, Reynoso N, Cavalieri ML, Guglielmo MC, Areso MS, Gilligan T, Santucho F, Cabral G, Gregorio GL, Moreno R, Lutz MI, Panigasi AL, Saligari L, Caballero MT, Egües Almeida RM, Gutierrez Meyer ME, Neder MD, Davenport MC, Del Valle MP, Santidrian VS, Mosca G, Garcia Domínguez M, Alvarez L, Landa P, Pota A, Boloñati N, Dalamon R, Sanchez Mercol VI, Espinoza M, Peuchot JC, Karolinski A, Bruno M, Borsa A, Ferrero F, Bonina A, Ramonet M, Albano LC, Luedicke N, Alterman E, Savy V, Baumeister E, Chappell JD, Edwards KM, Melendi GA, Polack FP. Pediatric hospitalizations associated with 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) in Argentina. N Engl J Med. 2010. 362:45–55.

23. Domínguez-Cherit G, Lapinsky SE, Macias AE, Pinto R, Espinosa-Perez L, de la Torre A, Poblano-Morales M, Baltazar-Torres JA, Bautista E, Martinez A, Martinez MA, Rivero E, Valdez R, Ruiz-Palacios G, Hernández M, Stewart TE, Fowler RA. Critically Ill patients with 2009 influenza A (H1N1) in Mexico. JAMA. 2009. 302:1880–1887.

24. Toll DB, Janssen KJ, Vergouwe Y, Moons KG. Validation, updating and impact of clinical prediction rules: a review. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008. 61:1085–1094.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download