Abstract

A 51-yr-old female was referred to our outpatient clinic for the evaluation of generalized edema. She had been diagnosed with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP). She had taken no medicine. Except for the ITP, she had no history of systemic disease. She was diagnosed with systemic lupus erythematosus. Immunosuppressions consisting of high-dose steroid were started. When preparing the patient for discharge, a generalized myoclonic seizure occurred at the 47th day of admission. At that time, the laboratory and neurology studies showed hyperglycemic hyperosmolar syndrome. Brain MRI and EEG showed brain atrophy without other lesion. The seizure stopped after the blood sugar and serum osmolarity declined below the upper normal limit. The patient became asymptomatic and she was discharged 10 weeks after admission under maintenance therapy with prednisolone, insulin glargine and nateglinide. The patient remained asymptomatic under maintenance therapy with deflazacort and without insulin or medication for blood sugar control.

Seizure in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is considered to be one of the major manifestations of the disease. The prevalence of seizure has been documented as about 10 to 20% in the patients with SLE (1, 2). This neuropsychiatric event is likely to be primary to the SLE or secondary due to other concomitant conditions, including infection, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, metabolic derangement and the toxic effects of therapy (3, 4). Hyperglycemic hyperosmolar syndrome (HHS) is a metabolic emergency, and it commonly occurs in elderly, disabled people with type 2 diabetes. The report of Sament and Schwartz in 1957 is widely credited as the original description of HHS. The proposed criteria for HHS are a plasma glucose concentration > 33.3 mM/L, a serum carbon dioxide concentration > 15 mM/L, no or mild ketonuria, absent to mild ketonemia, a serum osmolarity > 320 mM/kg and mental change (5). However, HHS without other metabolic derangement and that occurs in a patient with lupus nephritis without diabetes and who received short term steroid therapy is a very rare complication.

A 51-yr-old female was referred to our outpatient clinic for the evaluation of generalized edema on November 17, 2009. Two years previously, she had been diagnosed with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP). She had taken no medicine. Except for the ITP, she had no history of systemic disease like diabetes or hypertension. On admission, her blood pressure was 140/80 mmHg with a pulse rate of 76 beats/min. Her lower extremities showed pretibial pitting edema of grade 4. The patient also reported foamy urine for several days.

The chest radiography revealed cardiomegaly (the CT ratio was 0.54) and bilateral pleural effusions. The ECG showed normal sinus rhythm. Both kidneys showed diffusely increased parenchymal echogenicity with partially obliteration of the corticomedullary differentiation and a normal range of size (the right kidney was 10.3 cm by 4.5 cm in size, and the left kidney was 9.5 cm by 4.5 cm in size).

The laboratory findings showed nephrotic syndrome with generalized edema; the 24 hr urine protein was 5.3 g/24 hr, the total cholesterol was 7 mM/L (normal: < 5.2 mM/L) and the serum albumin was 22 g/L (normal: 35-52 g/L). On admission, the fasting blood glucose and hemoglobin A1C (HbA1c) were 5.4 mM/L and 0.05 Hb fraction, respectively. The blood urea nitrogen and serum creatinine were 20.6 mM/L (normal: 2.6-7.3 mM/L) and 0.23 mM/L (normal: 0.05-0.11 mM/L). In addition, the patient had a positive antinuclear antibody titer at 1:1,600 (normal:negative), positive antibodies against double-stranded DNA at 400 IU/mL (normal: < 100 IU/mL) and she was negative for antiphospholipid antibodies. The complement C3 and C4 levels were low at 0.28 g/L (normal: 0.76-1.39 g/L) and 0.073 g/L (normal: 0.12-0.37 g/L), respectively. She was diagnosed with systemic lupus erythematosus by the American College of Rheumatology criteria (6). At diagnosis, the SLEDAI score was 14. At the 6th day of admission, a renal biopsy was performed. That showed diffuse global glomerulonephritis with active lesion and IV-G(A) by the ISN/RPS classification (7).

Immunosuppressions consisting of high-dose steroid (methylprednisolone 750 mg for 3 days followed by prednisolone 60 mg), cyclophosphamide pulses (500 mg at the 6th and 36th day of admission), as well as plasma exchange were all started. In addition, she had oliguria that was refractory to diuretics, and this led us to start hemodialysis. After four session of hemodialysis, the oliguria was resolved. The clinical course was complicated by thrombocytopenia, which might be due to cyclophosphamide. The peripheral blood smear revealed normocytic normochronic anemia and thrombocytopenia without abnormal cells. There was no clinical evidence of infection or disease flare up.

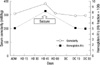

While maintaining a stable clinical course, a generalized myoclonic seizure occurred at the 47th day of admission. At that time, her body temperature was 36.1℃. The laboratory and neurology studies showed hyperglycemic hyperosmolar syndrome with a blood glucose level of > 44.4 mM/L, the serum osmolarity was 382 mM/kg (normal: 275-300 mM/kg) and the hemoglobin A1c was 0.082 Hb fraction. The serum pH was 7.348 and the bicarbonate was 26.2 mM/L (normal: 21-28 mM/L). The urine dip stick test was negative for ketones. The other electrolyte levels were within the normal limits. Brain MRI and EEG showed brain atrophy without other lesion. The C-reactive protein was normal at 3.9 mg/L (normal: 0.1-4.7 mg/L). The complement C3 and C4 levels were 0.66 g/L (normal: 0.76-1.39 g/L) and 0.237 g/L (normal: 0.12-0.37 g/L), respectively. At shortly before seizure, the SLEDAI score was 12. The patient was treated with insulin and anticonvulsant medication. The seizure stopped after the blood sugar and serum osmolarity declined below the upper normal limit mentioned above. The patient became asymptomatic and she was discharged 10 weeks after admission under maintenance therapy with prednisolone 10 mg, insulin glargine 12 unit and nateglinide 270 mg. On follow-up 1, 2, and 3 month after discharge, the HbA1c was 0.051, 0.049, and 0.06 Hb fraction, respectively. The changes of laboratory findings according to treatment are showed in Figs. 1, 2. The patient remained asymptomatic under maintenance therapy with deflazacort 12 mg and without insulin or medication for blood sugar control.

In patients with lupus nephritis, the causes of seizure are a multiplicity of different factors, such as CNS involvement of SLE, infections, hypertension and metabolic derangement. A large prospective study reported that infection was the most common cause of neurologic episodes and primary involvement of SLE was the secondary cause (8). The presence of seizure increases the risk of death in patients with SLE by approximately 2-fold (2, 9). When seizure is noted in patients with lupus nephritis, identifying the cause and proper treatment are important to improve survival. Most studies have revealed that reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome and cerebral vascular accident are other important causes of seizure in patients with lupus nephritis. By contrast, the neurologic episodes by purely metabolic derangement without infection or CNS lupus are very rare, and especially HHS was a seldom cause of seizure (8).

Steroid is associated with the risk of hyperglycemia in patients with or without diabetes (10, 11). Steroid interfere at several steps in insulin signaling cascade. This inhibit insulin signalling in skeletal muscle and liver, resulting in reduced glucose uptake and glycogen systhesis, increased breakdown of skeletal muscle mass, increased hepatic glucose production. In additions, steroid increase whole body lipolysis, resulting in increased nonesterified fatty acids (NEFA) and triglyceride (TG). Augmented levels of NFEA and TG may enhance the accumulation of intracellular lipids, which impair glucose metabolisms and induce hepatic steatosis, dyslpidemia. Steroid most likely exert inhibitory effects in the beta-cell after exposure, resulting decreased beta-cell insulin production (12-14). Diabetes develops in 5%-7% of the patients on steroid (15). Steroid-induced diabetes improves with reducing the dose of steroid. Acute complications, like HHS or diabetic ketoacidosis, rarely develop. As an acute complication of diabetes, the overall mortality of HHS is in the range of 10%-50%. However, when therapy is promptly instituted, the mortality rate can be reduced. The earliest symptoms of marked hyperglycemia include polyuria, polydipsia and weight loss. As degree of hyperglycemia progresses, patients experience neurologic symptoms (5). Treatment is targeted towards 1) correcting the intravascular volume and electrolyte derangements; 2) decreasing the hyperglycemia and hyperosmolarity by insulin; and 3) identifying and managing the comorbidities triggering the HHS (5, 16).

Althought hyperglycemia due to steroid therapy is a common, but acute complication of diabetes, HHS as a first manifestation is a very rare event. Our case showed that seizure developed due to HHS despite of the short-term steroid therapy. We should consider HHS as a cause of seizure in patient with lupus nephritis and who are treated with steroid.

In conclusion, our case highlights the importance of regular blood glucose testing during or before high-dose steroid therapy.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Appenzeller S, Cendes F, Costallat LT. Epileptic seizures in systemic lupus erythematosus. Neurology. 2004. 63:1808–1812.

2. Ward MM, Pyun E, Studenski S. Mortality risks associated with specific clinical manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Intern Med. 1996. 156:1337–1344.

3. Sanna G, Bertolaccini ML, Mathieu A. Central nervous system lupus: a clinical approach to therapy. Lupus. 2003. 12:935–942.

4. Kim BW, Kim JG, Ha SW, Lee HJ, Han JH, Jung SW, Nam JH, Park SH, Lee SH. Clinical manifestation and prognostic factors in nonketotic hyperosmolar coma. J Korean Diabetes Assoc. 1999. 23:575–584.

5. Rosenbloom AL. Hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state: an emerging pediatric problem. J Pediatr. 2010. 156:180–184.

6. Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1997. 40:1725.

7. Markowitz GS, D'Agati VD. Classification of lupus nephritis. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2009. 18:220–225.

8. Wong KL, Woo EK, Yu YL, Wong RW. Neurological manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus: a prospective study. Q J Med. 1991. 81:857–870.

9. Rabbani MA, Habib HB, Islam M, Ahmad B, Majid S, Saeed W, Shah SM, Ahmad A. Survival analysis and prognostic indicators of systemic lupus erythematosus in Pakistani patients. Lupus. 2009. 18:848–855.

10. Park SY, Kim SY, Kim DI, Kim HS, Yang SJ, Park JR, Kim DJ, Yoo HJ, Kwon SB, Baik SH. A case of hyperglycemic hyperosmolar syndrome induced by steroid treatment for idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. J Korean Diabetes Assoc. 2005. 29:571–573.

11. Shin MJ, Kim YO, Park JM, Bok HJ, Song KH, Yoon SA, Bang BK. Diabetic ketoacidosis after steroid administration for minimal change disease. Korean J Nephrol. 1999. 18:194–197.

12. Schäcke H, Döcke WD, Asadullah K. Mechanisms involved in the side effects of glucocorticoids. Pharmacol Ther. 2002. 96:23–43.

13. Van Raalte DH, Ouwens DM, Diamant M. Novel insights into glucocorticoid-mediated diabetogenic effects: towards expansion of therapeutic options? Eur J Clin Invest. 2009. 39:81–93.

14. Simmons PS, Miles JM, Gerich JE, Haymond MW. Increased proteolysis. An effect of increases in plasma cortisol within the physiologic range. J Clin Invest. 1984. 73:412–420.

15. Pyörälä K, Suhonen O, Pentikäinan P. Steroid therapy and hyperosmolar non-ketotic coma. Lancet. 1968. 1:596–597.

16. Milionis HJ, Elisaf MS. Therapeutic management of hyperglycaemic hyperosmolar syndrome. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2005. 6:1841–1849.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download