Abstract

Severe congenital neutropenia is a heterozygous group of bone marrow failure syndromes that cause lifelong infections. Mutation of the ELANE gene encoding human neutrophil elastase is the most common genetic alteration. A Korean female pediatric patient was admitted because of recurrent cervical lymphadenitis without abscess formation. She had a past history of omphalitis and isolated neutropenia at birth. The peripheral blood showed a markedly decreased absolute neutrophil count, and the bone marrow findings revealed maturation arrest of myeloid precursors at the promyelocyte to myelocyte stage. Her direct DNA sequencing analysis demonstrated an ELANE gene mutation (c.607G > C; p.Gly203Arg), but her parents were negative for it. She showed only transient response after subcutaneous 15 µg/kg/day of granulocyte colony stimulating factor administration for six consecutive days. During the follow-up observation period, she suffered from subsequent seven febrile illnesses including urinary tract infection, septicemia, and cellulitis.

Severe chronic neutropenia is a congenital condition defined as an absolute neutrophil count (ANC) of less than 500/µL for at least three months (1, 2). Generally, underlying hematologic disorders, autoimmune diseases, viral infections, or drugs causing neutropenia should be excluded. There are three categories according to the onset time or pattern of variation of neutrophil levels: congenital, cyclic, and idiopathic. Among them, severe congenital neutropenia (SCN) is an inborn disorder with maturation arrest of the early stage of granulopoiesis associated with various genetic abnormalities (3). In addition, cyclic neutropenia (CN) is a related disorder characterized by periodic oscillation of the peripheral neutrophil count, with an average 21-day frequency (1, 2). Among several associated genetic mutations, the variants of the ELANE sequence comprise approximately 50% of the genetic causes of SCN and nearly all of CN (4), and it is known to be correlated with more severe neutropenia and serious clinical manifestations in SCN (5). We herein introduce a Korean girl with typical features of SCN and a novel ELANE gene mutation.

A 9-month-old girl who was born on September 17th, 2009 was transferred to our hospital with prolonged fever and recurrent cervical lymphadenitis on June 25th, 2010. Her initial laboratory tests revealed severe neutropenia (ANC 90/µL) and increased acute phase reactants (erythrocyte sedimentation rate 97 mm/hr and C-reactive protein 7.9 mg/dL). She had a past history of admission to the neonatal intensive care unit at another hospital at birth due to omphalitis. The ANC was also low (100/µL) at that time. Her course of development was normal, and she had no congenital malformation suggestive of specific syndromes associated with neutropenia. Family history was nonspecific, and she had no siblings.

The cervical contrast enhanced computed tomography (CT) was performed to exclude abscess formation or deep neck infection that would need incision or aspiration. There was no definite drainable lesion (Fig. 1). Bone marrow (BM) findings showed early-stage maturation arrest of myelopoiesis (cellularity 80%-100%, myeloblasts 3.0%, promyelocytes 0.7%, myelocytes 2.2%, metamyelocytes 0.5%, band neutrophils 0.2%, and segmented neutrophils 0.0%), with an M:E ratio of 0.43:1 (Fig. 2). There was no evidence of malignant involvement in the BM. The chromosome study was normal (46, XX).

Considering her past history and physical examination, SCN associated with ELANE abnormality was suspected. Direct DNA sequencing analysis of the ELANE gene demonstrated a substitution of the 607th base (G to C) in exon 5, resulting in a change of the 203rd codon (glycine to arginine), which is a novel variation of SCN (c.607G > C; p.Gly203Arg) (Fig. 3). Her parents' tests were negative. The primers used in sequencing were GGACTTCCCAACCCTGAC (forward) and AGCCAAGGAGCATCAAACAC(reverse).

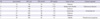

She had no increase in her ANC despite daily administration of subcutaneous 5-10 µg/kg granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G-CSF). After management with an increased dose (15 µg/kg/day) of G-CSF for six consecutive days, she recovered and was discharged with a increased ANC (11,110/µL) (Fig. 4). However, the ANC was again decreased at 990/µL when she visited our outpatient clinic one week after cessation of the G-CSF injections, and reduced to 130/µL after one month. She has suffered subsequent seven episodes of febrile illnesses until the present (Table 1). All of them were managed with prompt administration of intravenous empiric broad-spectrum antibiotics, cefepime.

SCN is a very rare condition that is diagnosed when the ANC is less than 500/µL from birth, with myeloid cell differentiation arrest at an early stage in the BM (1, 3). Patients suffer from life-long infections. CN is also a congenital disorder of granulopoiesis characterized by periodic oscillations in the number of circulating neutrophils (1, 2). BM findings of patients with CN vary with the cycle. Patients experience infections when the neutrophil count drops below 500/µL and approaches zero. Both SCN and CN are related to an ELANE alteration associated with sporadic or autosomal dominant inheritance (6).

SCN is a genetically heterozygous disease group with several gene mutations and various modes of inheritance (3, 7). There are some correlations between the mutant gene and clinical manifestations (7). For example, patients with the HAX1 abnormality show developmental delay or epilepsy with autosomal recessive inheritance (Kostmann syndrome), while patients with the ELANE mutation, which arises sporadically or follows autosomal dominant inheritance, have no neurological problems.

The female patient we herein report showed typical clinical manifestations of SCN. Her diagnosis was delayed, however, until nine months of age, because her past history of an umbilical cord infection and isolated severe neutropenia was overlooked. It is important to reconsider patients' history and laboratory tests in the case of recurrent bacterial infections. Since the patient had no anomalous morphology or neurological problems, we first suspected the ELANE gene mutation. If the patients show any malformations, Fanconi anemia/Schwachman-Diamond syndrome (skeletal abnormality), dyskeratosis congenita (nail dystrophy), or Diamond-Blackfan syndrome (anomaly of face or hand) should be considered (8).

Mutation of the ELANE gene (chromosome 19p13.3) encoding human neutrophil elastase (NE) is the most common genetic alteration in SCN (3). It comprises about 50% of SCN and nearly all of CN (3, 4). There have been about 50 reported ELANE variants in SCN and CN worldwide. There are some cases of Korean SCN patients, but until today, a genetically confirmed ELANE gene mutation was the only one in Korea (c.170C > T; p.Ala57Val) (9).

Neutrophils play a key role in innate immunity and the host's defense mechanisms by phagocytosing, killing, and digesting bacteria and fungi (10). In particular, azurophilc (primary) granules in the neutrophil, which are formed during the promyelocytic stage, contain several important proteins (myeloperoxidase, cathepsin G, elastase, proteinase 3, bactericidal/permeability-increasing protein, and defensin) essential for antibacterial activity. Among them, NE attacks gram negative bacteria like Klebsiella pneumoniae or Escherichia coli (11). In neutrophils in which NE is inactivated, bacteria escape from the phagosome, resulting in increase of bacterial survival (12). Although the entire pathophysiology of how the ELANE mutation develops in neutropenia is unknown, recently it is believed that the mutant NE tends to be misfolded, which leads to apoptosis of myeloid progenitor cells through an 'unfolded protein response' by the endoplasmic reticulum (13).

For those reasons, there are few mature neutrophils, while promyelocytes are normally present; that is the so-called 'maturation arrest' in the BM, and thus patients suffer from lifelong infections in SCN. Morphologically prominent vacuolations or aberrations of azurophilc granules may appear in the BM (7). Infections include bacterial illnesses, such as a urinary tract infection, pneumonia, omphalitis, septicemia, lymphadenitis, otitis media, cellulitis, and fungal disease like oral thrush.

Neutrophils contribute to tissue injury and reconstitution as well as play a role in host-defense cells (14). Thus, absence of pus at infection sites is the characteristic feature of SCN, as demonstrated by the neck CT of the patient in this study (7).

As a treatment of choice, the Severe Chronic Neutropenia International Registry recommends that the G-CSF injection is started at a dose of 5 µg/kg/day and continued in upward 2-fold adjustments until the ANC reaches over 1,000-1,500/µL (15). Generally, SCN patients require a higher dose of G-CSF (median 7.3-23.0 µg/kg/day, maximum 242.4 µg/kg/day) compared to cyclic or idiopathic neutropenia patients. About 90% of SCN patients respond to G-CSF treatment, but the remainder have only a temporary or no response to G-CSF (16). Although the predictors of poor response are not yet demonstrated, most refractory cases have very low initial ANC levels. In addition, the ELANE gene mutation is known to be associated with more severe neutropenia and serious clinical manifestations in SCN (5).

Although septic mortality is markedly decreased by G-CSF treatment, the cumulative incidence of myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) or acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in SCN is about 20% after 10 yr treatment (17). It is controversial whether SCN is an obvious precancerous condition, or the G-CSF treatment contributes to evolution to MDS/AML. Considering that cyclic or idiopathic neutropenia patients do not develop MDS/AML in spite of G-CSF administration, and refractory SCN patients who were exposed to a higher dose of G-CSF tend to develop MDS/AML, a combination of both theories is also possible. In the case of non-responders, stem cell transplantation from an HLA-identical sibling is the optimal therapeutic modality (8, 18).

In this case, the patient showed only temporary response to subcutaneous 15 µg/kg/day of G-CSF for six consecutive days. We have not yet increased the dose of G-CSF due to a financial problem associated with standards of Korean medical insurance. To control infections, we selected the 4th generation cephalosporine (cefepime) empirically to cover both Gram positive and negative bacteria including Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Total seven febrile episodes were successfully treated without complication by immediate intravenous antibiotic therapy. There has been no evidence of fungal infection or MDS/AML yet. Since she has no siblings and is very young, we closely follow her, with the idea of stem cell transplantation in reserve.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Contrast enhanced computed tomography of neck revealed conglomerated prominent enlarged lymph nodes in the internal jugular and posterior cervical chain (arrow). There was no drainable pus at the infection site.

Fig. 2

Microscopic examination of the bone marrow aspirate smear. (A) It revealed markedly decreased granulocytic precursors (Wright/Giemsa stain, × 400). (B) Myeloblasts and promyelocytes with prominent vacuolations are present, while mature neutrophils are absent (Wright/Giemsa stain, × 1,000).

Fig. 3

Direct DNA sequencing analysis demonstrated a novel ELANE gene mutation (c.607G>C; p.Gly203Arg) (arrow) (A). In the case of her parents, no mutation was detected (B, C).

References

1. Dale DC, Cottle TE, Fier CJ, Bolyard AA, Bonilla MA, Boxer LA, Cham B, Freedman MH, Kannourakis G, Kinsey SE, Davis R, Scarlata D, Schwinzer B, Zeidler C, Welte K. Severe chronic neutropenia: treatment and follow-up of patients in the Severe Chronic Neutropenia International Registry. Am J Hematol. 2003. 72:82–93.

2. James RM, Kinsey SE. The investigation and management of chronic neutropenia in children. Arch Dis Child. 2006. 91:852–858.

3. Xia J, Bolyard AA, Rodger E, Stein S, Aprikyan AA, Dale DC, Link DC. Prevalence of mutations in ELANE, GFI1, HAX1, SBDS, WAS, and G6PC3 in patients with severe congenital neutropenia. Br J Haematol. 2009. 147:535–542.

4. Horwitz MS, Duan Z, Korkmaz B, Lee HH, Mealiffe ME, Salipante SJ. Neutrophil elastase in cyclic and severe congenital neutropenia. Blood. 2007. 109:1817–1824.

5. Bellanné-Chantelot C, Clauin S, Leblanc T, Cassinat B, Rodrigues-Lima F, Beaufils S, Vaury C, Barkaoui M, Fenneteau O, Maier-Redelsperger M, Chomienne C, Donadieu J. Mutations in the ELA2 gene correlate with more severe expression of neutropenia: a study of 81 patients from the French Neutropenia Register. Blood. 2004. 103:4119–4125.

6. Dale DC, Person RE, Bolyard AA, Aprikyan AG, Bos C, Bonilla MA, Boxer LA, Kannourakis G, Zeidler C, Welte K, Benson KF, Horwitz M. Mutations in the gene encoding neutrophil elastase in congenital and cyclic neutropenia. Blood. 2000. 96:2317–2322.

7. Klein C. Congenital neutropenia. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2009. 344–350.

8. Yoo ES. Neutropenia in children. Korean J Pediatr. 2009. 52:633–642.

9. Lee ST, Yoon HS, Kim HJ, Lee JH, Park JH, Kim SH, Seo JJ, Im HJ. A novel mutation Ala57Val of the ELA2 gene in a Korean boy with severe congenital neutropenia. Ann Hematol. 2009. 88:593–595.

10. Segal AW. How neutrophils kill microbes. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005. 23:197–223.

11. Belaaouaj A, McCarthy R, Baumann M, Gao Z, Ley TJ, Abraham SN, Shapiro SD. Mice lacking neutrophil elastase reveal impaired host defense against gram negative bacterial sepsis. Nat Med. 1998. 4:615–618.

12. Weinrauch Y, Drujan D, Shapiro SD, Weiss J, Zychlinsky A. Neutrophil elastase targets virulence factors of enterobacteria. Nature. 2002. 417:91–94.

13. Xia J, Link DC. Severe congenital neutropenia and the unfolded protein response. Curr Opin Hematol. 2008. 15:1–7.

14. Nathan C. Neutrophils and immunity: challenges and opportunities. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006. 6:173–182.

15. Dale DC, Bolyard AA, Schwinzer BG, Pracht G, Bonilla MA, Boxer L, Freedman MH, Donadieu J, Kannourakis G, Alter BP, Cham BP, Winkelstein J, Kinsey S, Zeidler C, Welte K. The Severe Chronic Neutropenia International Registry: 10-year follow-up report. Support Cancer Ther. 2006. 3:220–231.

16. Dale DC, Bonilla MA, Davis MW, Nakanishi AM, Hammond WP, Kurtzberg J, Wang W, Jakubowski A, Winton E, Lalezari P, Robinson W, Glaspy JA, Emerson S, Gabrilove J, Vincent M, Boxer LA. A randomized controlled phase III trial of recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (filgrastim) for treatment of severe chronic neutropenia. Blood. 1993. 81:2496–2502.

17. Rosenberg PS, Alter BP, Bolyard AA, Bonilla MA, Boxer LA, Cham B, Fier C, Freedman M, Kannourakis G, Kinsey S, Schwinzer B, Zeidler C, Welte K, Dale DC. Severe Chronic Neutropenia International Registry. The incidence of leukemia and mortality from sepsis in patients with severe congenital neutropenia receiving long-term G-CSF therapy. Blood. 2006. 107:4628–4635.

18. Zeidler C, Welte K, Barak Y, Barriga F, Bolyard AA, Boxer L, Cornu G, Cowan MJ, Dale DC, Flood T, Freedman M, Gadner H, Mandel H, O'Reilly RJ, Ramenghi U, Reiter A, Skinner R, Vermylen C, Levine JE. Stem cell transplantation in patients with severe congenital neutropenia without evidence of leukemic transformation. Blood. 2000. 95:1195–1198.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download