Abstract

We report a case of 54-yr-old woman who presented with 4-extremities weakness and sensory changes, followed by cervical spinal cord lesion in magnetic resonance imaging. Based on the suspicion of spinal tumor, spinal cord biopsy was performed, and the histology revealed multinucleated giant cells, lymphocytes and aggregated histiocytes within granulomatous inflammation, consistent with non-caseating granuloma seen in sarcoidosis. The patient was treated with corticosteroid, immunosuppressant and thalidomide for years. Our case indicates that diagnosis of spinal cord sarcoidosis is challenging and may require histological examination, and high-dose corticosteroid and immunosuppressant will be a good choice in the treatment of spinal cord sarcoidosis, and the thalidomide has to be debated in the spinal cord sarcoidosis.

Sarcoidosis is a systemic granulomatous disease of unknown origin, characterized by the presence of noncaseating granuloma in affected organs (1). Lesions are commonly seen in the lungs, lymphatic system, eyes, skin, liver, spleen, salivary glands, heart, nervous system, muscles, and bones (1, 2). Although neurosarcoidosis is a rare manifestation of sarcoidosis, the clinical symptoms can be devastating and occasionally life-threatening. The diagnosis of neurosarcoidosis can be challenging because the disease can present with a lot of symptoms and diverse radiologic findings (1-5). Among them, spinal sarcoidosis is a very rare entity, occurring in < 1%, and can be manifested as intramedullary, intradural extramedullary, intraspinal epidural spaces and in vertebral bodies (6). In Korea, only a few cases of neurosarcoidosis involving brain, spinal nerve root, peripheral nerve and spinal dura, have been reported with or without histological confirmation in the literature. However spinal cord sarcoidosis has not been documented in Korea. In general, patients with spinal sarcoidosis are considered to be at high risk for severe neurological sequelae (7). The information available about spinal sarcoidosis management and diagnosis comes from a few case reports, small series and expert opinions (8-10). However, the documents gave conflicting conclusions regarding the treatment, including corticosteroids and alternative immunosuppressants (6, 7). We recently experienced a patient with isolated spinal cord sarcoidosis, which was confirmed by tissue biopsy and well responsive to high-dose corticosteroid and immunosuppressant.

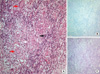

A 54-yr-old woman, with no significant past medical history, presented with progressive 4-extremities weakness and sensory changes, followed by urinary difficulty since 1 month ago and was admitted to our hospital in October 2007. Physical examination revealed increased deep tendon reflex, positive Babinski sign and decreased motor power with medical research council (MRC) grade 2 strength in the right side and MRC grade 4 strength in the left side. Pinprick and temperature sensation was decreased from C4, dominantly in the left side. Vibration and proprioception was decreased, dominantly in the right side. Hoffman's and Tromner's sign were increased in both hands. Initial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed increased T2 signal from C4 to C6 level, edematous expansion of the cord and intense nodular enhancement (Fig. 1A). Based on the MRI, spinal cord tumor, demyelinating disease involving multiple sclerosis, neuromyelitis optica and acute tranverse myelitis were suspected. Serological studies for systemic autoimmunity, including rheumatoid factor and antinuclear, anti-dsDNA, anti-SSA/SSB, and antiphospholipid antibodies, showed no abnormality. The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis including biochemistry, IgG index and oligoclonal band was normal. One month later, the follow-up spinal MRI showed the more extended lesion relative to previous MRI, and which highly suggested the spinal cord tumor such as intramedullary astrocytoma (Fig. 1B). Based on the suspicion of intramedullary astrocytoma, the laminectomy and tissue biopsy of 2 µL, which showed yellowish color, were performed at the central portion of dorsal column in affected cervical cord lesion. Postoperatively, patient's neurologic deficits were not aggravated and, unexpectedly, the histology of biopsy revealed non-caseating granuloma without malignant cell (Fig. 2A). AFB and PAS staining of tissue were negative (Fig. 2B, C). The diagnosis was changed from intramedullary astrocytoma to neurosarcoidosis. Angiotesin converting enzyme (ACE) was mildly elevated to 56 (U/L; normal, < 52 U/L). On the systemic evaluations, there was no disease activity on other organs with using brain MRI, chest and abdominal computed tomography and nerve conduction study (NCS). The patient was treated with high-dose corticosteroid (60 mg/day) followed by methotrexate (10 mg/week) for over 2 yr. Two years later, cervical spinal cord lesion was much improved in the spinal MRI (Fig. 1D), however clinical symptoms of weakness and sensory change were not definitely improved. Recently, the patient had to stop corticosteroid medication because of the cellulitis in the left leg. Instead, we tried thalidomide 100 mg daily for 1 month with the goal of titrating up to 400 mg per day, which had been reported to be effective in the refractory neurosarcoidosis (11). However the patient refused high-dose thalidomide due to severe fatigue and high cost, and just treated with low-dose thalidomide (100 mg/day) and treatment did not show distinct effect in our patient.

The spinal cord sarcoidosis is very rare and the diagnosis of this entity is difficult, as there are no pathognomic diagnostic study for neurosarcoidosis (3, 12, 13). In general, this disease has been diagnosed clinically using MRI, lumbar puncture and attendant laboratory tests, and the diagnosis is possible when systemic sarcoidosis is detected in other organs involving lung, kidney, eye and skin. Spinal cord sarcoidosis may present as an idiopathic inflammatory demyelinating disease both clinically and radiologically (5). Only a positive biopsy of suspicious lesions in the central nervous system is considered to be definitive confirmation of the diagnosis of isolated neurosarcoidosis. Zajicek and colleagues established a diagnostic classification system for neurosarcoidosis that distinguished 'definite', 'probable' and 'possible' neurosarcoidosis based on tissue evidence of non-caseating granuloma and supportive evidence of sarcoid pathology in laboratory and imaging studies (13). However, biopsy should be cautiously considered if possible because of the risk involved in approaching the spinal cord. Our patient was initially suspected to have intramedullary astrocytoma or multiple sclerosis based on neurologic symptoms and MRI results. Of course, the possibility of multiple sclerosis was not high because the clinical symptoms and cervical lesion were gradually progressive for months. The spinal cord biopsy was challenging procedure, nevertheless the cord biopsy and laminectomy were performed for diagnostic confirmation in the consent of patient, and the histology of which was unexpectedly consistent with sarcoidosis. The histology revealed multinucleated giant cells, lymphocytes and aggregated histiocytes within granulomatous inflammation, consistent with non-caseating granuloma seen in sarcoidosis. This is a rare case confirmed by direct tissue biopsy in the spinal cord. A few cases with neurosarcoidosis have been reported, however most cases suggested only clinical manifestation without histology, or demonstrated indirect biopsy in the brain, meninges and lymph node (6-10).

With an initial treatment, we tried high dose corticosteroid and immunosuppressant. Systemic corticosteroids and immunosuppressive therapy are the treatment of choice for neurosarcoidosis, however which shows partial response especially in the spinal cord neurosarcoidosis (4, 6-10). Unfortunately, 25% of neurosarcoidosis still have a refractory course with steroid treatment and, and 20%-40% of those refractory patients will not respond to current conventional immunosuppressant (3). In our case, the clinical symptoms were initially severe and rapidly progressive, and therefore the combined therapy of high-dose corticosteroid and immunosuppressant was necessary. Combination with immunosuppressant was useful to improve symptom control and reduce corticosteroid-related side effects in some cases. Fortunately, our patient responded well to high-dose corticosteroid and immunosuppressant. Therefore, making a diagnosis of neurosarcoidosis was therapeutically essential, since corticosteroid and immunosuppressant treatment must be started and continued for years in order to prevent progression and permanent disability. A few reports have documented that the high-dose thalidomide (400 mg/day) was effective in the refractory neurosarcoidosis (11), and so we tried low-dose thalidomide (100 mg/day) for one month in our patient. However there was no clear evidence that thalidomide was effective in our case of neurosarcoidosis, although there was limitation on the dosage and duration of treatment compared with other cases.

Our case indicates that diagnosis of spinal cord sarcoidosis is not easy and may require histological examination, and high-dose corticosteroid and immunosuppressant will be a good choice in the treatment of spinal cord sarcoidosis, and the thalidomide has to be debated in the treatment of spinal cord sarcoidosis.

This is the first Korean case, to our knowledge, which shows an isolated spinal cord sarcoidosis confirmed by direct tissue biopsy and good response to corticosteroid and immunosuppressant.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

T2-weighted and gadolinium enhanced T1-weighted cervical MRI in the patient. (A) Initial cervical spine MRI (magnetic resonance image) revealed increased T2 signal from C4 to C6 level, edematous expansion of the cord and intense nodular enhancement. Based on the MRI, spinal cord tumor, demyelinating disease and acute tranverse myelitis were suspected. (B) One month later, the follow-up spinal MRI showed the extended lesion relative to previous MRI, and which highly suggested the spinal cord tumor such as intramedullay astrocytoma. (C) Demonstrates cervical spine MRI after laminectomy and tissue biopsy. (D) The patient was treated with high-dose corticosteroid and immunosuppressant for over 2 yr and spinal cord lesion was much resolved in MRI.

Fig. 2

Histopathology of the biopsied cervical cord lesion. (A) The specimen biopsied from the lesion contained multinucleated giant cells (red arrows), lymphocytes (black arrow) and aggregated histiocytes (white arrow) within granulomatous inflammation, consistent with non-caseating granuloma seen in sarcoidosis (H&E staining × 200). (B) The AFB staining of the specimen did not show the mycobacterium tuberculosis. PAS staining did not reveal the fungus.

References

1. Baughman RP, Lower EE, du Bois RM. Sarcoidosis. Lancet. 2003. 361:1111–1118.

2. Stern BJ. Neurological complications of sarcoidosis. Curr Opin Neurol. 2004. 17:311–316.

3. Hoitsma E, Faber CG, Drent M, Sharma OP. Neurosarcoidosis: a clinical dilemma. Lancet Neurol. 2004. 3:397–407.

4. Joseph FG, Scolding NJ. Neurosarcoidosis: a study of 30 new cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009. 80:297–304.

5. Shah R, Roberson GH, Curé JK. Correlation of MR imaging findings and clinical manifestations in neurosarcoidosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2009. 30:953–961.

6. Varron L, Broussolle C, Candessanche JP, Marignier R, Rousset H, Ninet J, Sève P. Spinal cord sarcoidosis: report of seven cases. Eur J Neurol. 2009. 16:289–296.

7. Scott TF, Yandora K, Valeri A, Chieffe C, Schramke C. Aggressive therapy for neurosarcoidosis: long-term follow-up of 48 treated patients. Arch Neurol. 2007. 64:691–696.

8. Caneparo D, Lucetti C, Nuti A, Cipriani G, Tessa C, Fazzi P, Bonuccelli U. A case of sarcoidosis presenting as a non-specific intramedullary lesion. Eur J Neurol. 2007. 14:346–349.

9. Bhagavati S, Choi J. Intramedullary cervical spinal cord sarcoidosis. Spinal Cord. 2009. 47:179–181.

10. Maroun FB, O'Dea FJ, Mathieson G, Fox G, Murray G, Jacob JC, Reddy R, Avery R. Sarcoidosis presenting as an intramedullary spinal cord lesion. Can J Neurol Sci. 2001. 28:163–166.

11. Hammond ER, Kaplin AI, Kerr DA. Thalidomide for acute treatment of neurosarcoidosis. Spinal Cord. 2007. 45:802–803.

12. Viñas FC, Rengachary S, Kupsky WJ. Spinal cord sarcoidosis: a diagnostic dilemma. Neurol Res. 2001. 23:347–352.

13. Zajicek JP, Scolding NJ, Foster O, Rovaris M, Evanson J, Moseley IF, Scadding JW, Thompson EJ, Chamoun V, Miller DH, McDonald WI, Mitchell D. Central nervous system sarcoidosis-diagnosis and management. QJM. 1999. 92:103–117.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download