Abstract

We report the first case of Susac syndrome in Koreans, in a 23-yr-old female patient who presented with sudden visual loss and associated neurological symptoms. Ophthalmic examination and fluorescein angiography showed multiple areas of branch retinal artery occlusion, which tended to recur in both eyes. Magnetic resonance imaging showed dot-like, diffusion-restricted lesions in the corpus callosum and left fornix, and audiometry showed low-frequency sensory hearing loss, compatible with Susac syndrome. She received immunosuppressive therapy with oral steroid and azathioprine. Three months later all the symptoms disappeared but obstructive vasculitis have been relapsing. This patient demonstrated the entire clinical triad of Susac syndrome, which tends to occur in young females. Although this disorder has rarely been reported in Asian populations, a high index of suspicion is warranted for early diagnosis and timely treatment.

Susac syndrome (SS) consists of the clinical triad of encephalopathy, branch retinal artery obstruction (BRAO) and hearing loss without prominent systemic manifestations (1-4). It is thought to be caused by pre-capillary arteriole obstruction of the brain, retina and inner ear due to damage from circulating anti-endothelial cell antibodies (3-5). These symptoms may not always occur, and disease presentation is often insidious (2, 4, 6), such that patients with initial presenting symptoms may be misdiagnosed. Although many patients with SS have been reported in Western countries, none has yet been reported in Korea.

A 23-yr-old woman visited the emergency clinic on November 23, 2011 with visual disturbance and a visual field defect in her left eye which had developed 1 day earlier. She had started to experience recurrent visual field defects in both eyes and headache 6 months earlier, and these symptoms became aggravated 1 month earlier. She denied having diabetes, hypertension, connective tissue disease, tuberculosis, hematologic disease or cardiovascular disease. She also stated that she had not used oral contraceptives and was not pregnant.

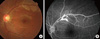

On initial examination, her pupils were reactive to light without relative afferent papillary defect. Corrected visual acuity was 20/20 in her right eye and 20/25 in her left eye. IOP was 18 mmHg in both eyes. Slit lamp examination revealed no abnormal findings in the anterior segment of both eyes. Fundoscopic examination showed an edematous lesion in the supra-temporal area of her left eye (Fig. 1A), and normal findings in her right eye. Fluorescein angiography (FA) revealed obstructive vasculitis in the supra-temporal branch of the retinal artery in her left eye (Fig. 1B). A visual field test showed an infra-nasal field defect in her left eye and a small field defect in her right eye (Fig. 2).

Two days later, the patient again visited the emergency clinic due to sudden hearing loss in her left ear, which had developed that morning. Pure tone audiometry showed sensory neuronal hearing loss at low-frequency in her left ear (Fig. 3). Three weeks later, she complained of a visual field defect in her right eye. A repeat FA showed BRAO in her right eye, but the signs of obstructive vasculitis in her left eye had disappeared. Two days later, she was admitted to the neurologic ward for tinnitus and severe headache with arm numbness.

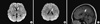

Laboratory tests, including for lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin antibody, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein, were all normal. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis showed a slight increase in protein concentration (74.4 mg/dL), without evidence of oligoclonal bands. There were no specific hematologic or rheumatologic abnormalities. Magnetic resonance (MR) imaging showed dot-like, diffusion-restricted lesions with T2 signal change in the corpus callosum and left fornix (Fig. 4A, B).

After considering all these findings, she was diagnosed with SS and started on high dose steroid therapy. Two months later, FA detected newly developed occlusive vasculitis in both eyes (Fig. 5). Follow-up sagittal Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) MR imaging showed a signal change in the area corresponding to that of the previous infarction in the corpus callosum (Fig. 4C), but there was no evidence of newly developed ischemic brain lesions. The dosage of oral steroids was maintained, and azathioprine (50 mg bid) was added. Three months later, her symptoms of headache, tinnitus and visual field defect had all resolved. However, FA showed new vasculitis and obstruction of the branch retinal artery, although all previously affected lesions had normalized.

We have described here a young female patient who showed the clinical triad of SS: BRAO, hearing loss and encephalopathy. To our knowledge, this is the first case report of SS in Korea. Since the first description of SS in 1977, hundreds of patients with SS have been reported, mainly in Western countries (3). Women are more frequently affected than men, with young white women between the age of 20 and 40 yr being most susceptible (3, 6). A MEDLINE search for SS in Asian populations showed only one case report, in a Japanese male (1).

Retinal arterial occlusion is rare in younger individuals (7), with nearly 75% of these patients being older individuals with retinal arterial occlusion caused by embolization of atheromatous plaques of the carotid artery (7, 8). Retinal arterial occlusion in younger patients is usually due to migraine, a coagulation abnormality, cardiac disease, trauma, drug abuse or connective tissue disease (7, 9). In patients with SS, localized retinal vasculitis rather than embolism is believed to cause arteriolar occlusions, which usually do not occur at bifurcations (10). BRAO tends to be bilateral, and to be multiple, widely disseminated in the retina, and temporally separated by as long as several months. The white material in the arterial lumen may represent aggregations of immune complexes or debris from damaged endothelium (11). A characteristic feature on FA is arterial wall hyperfluorescence, often proximal to sites of occlusion, as shown in our patient, and suggesting endothelial dysfunction (11).

Common neurological features of SS include severe headache, which may occur several months prior to other symptoms, and personality disorder (12). Due to the multifocal vasculitis, neurological manifestations are extremely variable and include ataxia, vertigo, corticospinal tract signs, and even seizure. On MRI, microinfarcts are best seen on T2 weighted images as hyperintense lesions (13). These microinfarcts are usually multifocal and located in the area of the corpus callosum, as seen in our patient (3, 4). CSF may contain a normal or high protein concentration. High protein concentration, coupled with an absence of oligoclonal bands, is typical, as in our patient (14).

Characteristic audiological findings in SS include low-frequency hearing loss, vertigo, and tinnitus. Our patient had both low-frequency hearing loss and tinnitus, which were likely due to microangiopathic lesions of the apical cochlea end arterioles (2).

The diagnosis of SS is often difficult because its characteristic signs often do not occur simultaneously or may be too subtle for the patient to notice (1, 15). In one case report, the patient presented with encephalopathy 10 yr before hearing loss, with recurrence of encephalopathy 18 yr later (2). Another patient experienced multiple BRAO episodes over 30 yr, followed by a Swiss-cheese like corpus callosum on MR imaging without signs of encephalopathy (1). Therefore, patients who manifest one of the clinical signs of SS should be suspected of this disorder. Although SS has been considered rare, it may be more common than reported (1, 13, 14).

As in many other autoimmune diseases, steroid therapy is the mainstay of treatment for SS (2-4). Initial high dose corticosteroid therapy, followed by tapering, has been recommended (2, 4). Additional immune suppressive treatment, with cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate mofetil, methotrexate, or cyclosporine, may be helpful (2). Many patients have improved after receiving intravenous immunoglobulin (2).

To avoid disastrous consequences, aggressive and timely treatment is needed, for a sufficient period of time (2). However, progression of SS may be insidious and the symptoms do not always occur together.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Fundus photo showing edematous lesions in the supra-temporal area (A). Fluorescein angiography, showing a hyperfluorescent arterial wall proximal to the obstructed branch retinal artery (B).

Fig. 2

Visual field test results, showing an infranasal field defect of the left eye corresponding to the obstructed lesion and a small area of visual field defect in the right eye.

References

1. Murata Y, Inada K, Negi A. Susac syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000. 129:682–684.

2. Rennebohm RM, Egan RA, Susac JO. Treatment of Susac's syndrome. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2008. 10:67–74.

3. Susac JO, Egan RA, Rennebohm RM, Lubow M. Susac's syndrome: 1975-2005 microangiopathy/autoimmune endotheliopathy. J Neurol Sci. 2007. 257:270–272.

4. Rennebohm R, Susac JO, Egan RA, Daroff RB. Susac's syndrome: update. J Neurol Sci. 2010. 299:86–91.

5. Jarius S, Neumayer B, Wandinger KP, Hartmann M, Wildemann B. Anti-endothelial serum antibodies in a patient with Susac's syndrome. J Neurol Sci. 2009. 285:259–261.

6. Martinet N, Fardeau C, Adam R, Bodaghi B, Papo T, Piette JC, Lehoang P. Fluorescein and indocyanine green angiographies in Susac syndrome. Retina. 2007. 27:1238–1242.

7. Trevino R, Pearlman R. Idiopathic recurrent branch retinal arterial occlusion in a young adult. Optom Vis Sci. 1998. 75:11–16.

8. Beatty S, Au Eong KG. Acute occlusion of the retinal arteries: current concepts and recent advances in diagnosis and management. J Accid Emerg Med. 2000. 17:324–329.

9. Recchia FM, Brown GC. Systemic disorders associated with retinal vascular occlusion. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2000. 11:462–467.

10. Gass JD, Tiedeman J, Thomas MA. Idiopathic recurrent branch retinal arterial occlusion. Ophthalmology. 1986. 93:1148–1157.

11. Notis CM, Kitei RA, Cafferty MS, Odel JG, Mitchell JP. Microangiopathy of brain, retina, and inner ear. J Neuroophthalmol. 1995. 15:1–8.

12. Susac JO, Hardman JM, Selhorst JB. Microangiopathy of the brain and retina. Neurology. 1979. 29:313–316.

13. O'Halloran HS, Pearson PA, Lee WB, Susac JO, Berger JR. Microangiopathy of the brain, retina, and cochlea (Susac syndrome). A report of five cases and a review of the literature. Ophthalmology. 1998. 105:1038–1044.

14. Susac JO. Susac's syndrome: the triad of microangiopathy of the brain and retina with hearing loss in young women. Neurology. 1994. 44:591–593.

15. Dörr J, Radbruch H, Bock M, Wuerfel J, Bruggemann A, Wandinger KP, Zeise D, Pfueller CF, Zipp F, Paul F. Encephalopathy, visual disturbance and hearing loss-recognizing the symptoms of Susac syndrome. Nat Rev Neurol. 2009. 5:683–688.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download