Abstract

Atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis (RAS) usually involves the ostium and the proximal one-third of the renal artery main branch. Percutaneous renal artery angioplasty with stent placement is a well recognized treatment for atherosclerotic RAS. Occasionally, atherosclerotic RAS involves renal artery bifurcations. However, stent implantation in atherosclerotic RAS involving bifurcation is not only troublesome, but also challenging because of side branch occlusion and in-stent restenosis (ISR). In the present report, we describe the use of drug-eluting stents (DES) with provisional T-stenting technique for the treatment of renal artery bifurcation lesion. Follow-up angiogram showed no significant ISR 18 months after the procedure. In the treatment of renal bifurcation lesions, a two-stent strategy using DES could be a viable option in selected patients.

Renal artery stenosis (RAS) is a progressive disease that may cause hypertension and chronic renal insufficiency. Percutaneous renal artery angioplasty with stent placement is a well recognized treatment for ostial and proximal RAS. Infrequently, atherosclerotic RAS can involve bifurcation of the renal artery, making treatment of this stenosis difficult and challenging (1). One challenge in interventional therapy for RAS with bifurcation is avoiding side branch occlusion; techniques developed in percutaneous coronary intervention might be used in this situation. When side branch occlusion occurs during renal artery intervention, two-stenting techniques might be useful. Another challenge is ISR. Prvious prospective nonrandomized trial couldn't support the role of DES in the treatment of RAS (2). However, if using an adequate sized DES and valid techniques, we considered DES as a possible solution. In the present report, we describe the use of DES with provisional T-stenting technique for the treatment of renal artery bifurcation lesion. In our patient, a follow-up angiogram showed no significant ISR 18 months after the procedure.

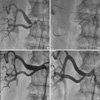

A 66-yr-old man with history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and atrial fibrillation was hospitalized for evaluation of chest pain and control of resistant hypertension on 17 July, 2009. Despite pharmacologic therapy of nebivolol (10 mg daily), amlodipine (5 mg daily), and hydrochlorothiazide (25 mg daily), his blood pressure remained elevated in the range of 180-190/70-90 mmHg. The creatinine was within the normal range (1.1 mg/dL). Coronary angiography was performed for evaluation of chest pain. The test revealed 80% stenosis of the proximal left circumflex artery and diffuse stenosis of the proximal to mid-right coronary artery followed by coronary stenting with the left circumflex artery and the right coronary artery. Subsequent to the evaluation of the resistant hypertension, a renal angiography was obtained, which revealed a nonvisualized left kidney and severe stenosis of the right renal artery bifurcation involving both branches (Fig. 1A). Contrast-enhanced abdominal computed tomography demonstrated atrophic change of the left kidney and stenosis of the right renal artery. On the 4th day of admission, the decision was made to treat the stenosis of the right renal artery bifurcation. An 8 Fr renal double curve (RDC) catheter (Boston Scientific, Natic, MA, USA) was positioned at the ostium of the right renal artery. Two 0.014-inch reflex upper soft wires (Cordis, Miami Lakes, FL, USA) were then placed into each branch vessel of the main renal artery. Kissing balloon angioplasty of the bifurcation was performed using appropriately sized balloons. After the angioplasty, a 7.0 × 24 mm Genesis stent (Cordis, Miami Lakes, FL, USA) was deployed into the main branch (upper pole). This resulted in a "snowplowing" effect, shifting plaque to the side branch (lower pole). A 3.5 × 12 mm PROMUS stent (Boston Scientific, Galway, Ireland) was then deployed into the side branch using provisional T-stenting technique (Fig. 1B). Finally, the main branch was post-dilated with a 6.0 × 12 mm ultrasoft SV balloon (Boston scientific, Natic, MA, USA) at 18 atm, and the side branch was post-dilated with a 3.5 × 12 mm Sprinter legend balloon (Medtronic, Minapolis, MN, USA) at 18 atm in a kissing fashion. An angiogram after stent placement demonstrated widely patent bifurcational stents with normal flow patency (Fig. 1C). Blood pressure was well controlled and the patient was discharged in stable condition. After 18 months, a follow-up angiogram showed mild stenosis in the main branch and the side branch ostium (Fig. 1D). Because the blood pressure was well controlled and lumen diameter loss was less than 30%, the lesion was not treated.

Atherosclerotic RAS is most often caused by plaque formation in the aortic wall with progression into the renal artery lumen, thereby inducing the typical appearance of the ostial (first 2 cm), usually eccentric, location of the lesion (3). These lesions are often elastic and respond poorly to balloon angioplasty alone, resulting in significant residual stenosis and restenosis (4). With the introduction of balloon-expandable metallic stents, a new treatment became available with improved post-interventional results and lower restenosis rates by preventing negative remodeling. In a meta-analysis of 1,322 patients, stent placement had a higher technical success rate and a lower restenosis rate than percutaneous transluminal renal angioplasty (5).

Renal artery stenosis involving bifurcation is not seen in the majority of clinical practices and, as a result, experience in treating renal artery bifurcation is limited (6). When treating bifurcation lesions, stent implantation in only one branch can result in obstruction of the remaining branch. Bifurcation lesions are frequent in coronary arteries, and treatment with a stent is common even though it is difficult (7). Studies from the bare-metal stent (BMS) era consistently demonstrated that the one-stent approach was superior to the two-stent approach; this view remains controversial in the DES era (8). Although two-stent strategy has not been proven to be superior in the treatment of coronary arteries, this might not be true in renal artery stenosis. Because the size of the renal artery is usually larger than the coronary artery, when abrupt closure of a side branch occurs, stenting becomes necessary to preserve branch patency. In our case, main branch stenting resulted in side branch occlusion, and the diameter of the side branch was not small enough (3.5 mm) to scarify. Therefore, we decided to treat the lesion with two-stenting strategy.

Another problem is in-stent restenosis (ISR). Restenosis rates after successful renal stent placement vary from 6% up to 40% depending on the definition of restenosis, which is still controversial in the DES era (9). In the GREAT trial, ISR, late lumen loss, and repeat revascularization after renal artery stent implantation were lower in the sirolimus-eluting stent group than in the BMS group, but the difference was not statistically significant (2). However, in the GREAT trial, only 5 and 6 mm stents were used in the study. Some of the treated arteries in both patient groups were larger in diameter than 6mm, and under-stenting might have influenced the outcome. Usually, ISR rates in small renal arteries are much higher than those in other renal arteries. We determined that if we could size the stent diameter at a ratio of 1.0-1.1:1 to the distal reference diameter, DES might reduce the occurrence of restenosis, as has been demonstrated in coronary arteries. In our case, the reference diameter of the side branch was 3.5 mm, so we were able to use an adequately sized drug-eluting stent (PROMUS, Boston Scientific).

There are limited data on the use of DES in renal arteries for the treatment of complex stenosis involving bifurcation lesion. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported case of "provisional T-stenting" using DES for bifurcation lesions in the renal artery with documented good long-term (18 months) angiographic outcome. In the treatment of renal bifurcation lesions, a two-stent strategy using DES could be a viable option in selected patients.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Renal angiogram of the patient. (A) Significant stenosis at right renal artery bifurcation. (B) Deployment of Genesis stent at main branch and PROMUS stent at side branch using provisional T-stenting technique. (C) After stent placement revealing a patent renal artery with no residual stenosis. (D) Follow-up angiogram showing 20% mild stenosis in main branch and minimal stneosis in side branch.

References

1. Missouris CG, Buckenham T, Cappuccio FP, Macgregor GA. Renal artery stenosis: a common and important problem in patients with peripheral vascular disease. Am J Med. 1994. 96:10–14.

2. van de Ven PJ, Kaatee R, Beutler JJ, Beek FJ, Woittiez AJ, Buskens E, Koomans HA, Mali WP. Arterial stenting and balloon angioplasty in ostial atherosclerotic renovascular disease: a randomized trial. Lancet. 1999. 353:282–286.

3. Leertouwer TC, Gussenhoven EJ, Bosch JL, van Jaarsveld BC, van Dijk LC, Deinum J, Man In't Veld AJ. Stent placement for renal arterial stenosis: where do we stand? A meta-analysis. Radiology. 2000. 216:78–85.

4. Zeller T, Rastan A, Rothenpieler U, Müller C. Restenosis after stenting of atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis: Is there a rationale for the use of drug-eluting stents? Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2006. 68:125–130.

5. Lefèvre T, Louvard Y, Morice MC, Dumas P, Loubeyre C, Benslimane A, Premchand RK, Guillard N, Pièchaud JF. Stenting a bifurcation lesions: classification, treatments, and results. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2000. 49:274–283.

6. Al Suwaidi J, Yeh W, Cohen HA, Detre KM, Williams DO, Holmes DR Jr. Immediate and one-year outcome in patients with coronary bifurcation lesions in the modern era (NHLBI dynamic registry). Am J Cardiol. 2001. 87:1139–1144.

7. Colombo A, Moses JW, Morice MC, Ludwig J, Holmes DR Jr, Spanos V, Louvard Y, Desmedt B, Di Mario C, Leon MB. Randomized study to evaluate sirolimus-eluting stents implanted at coronary bifurcation lesions. Circulation. 2004. 109:1244–1249.

8. Zähringer M, Pattynama PM, Talen A, Spoval M. Drug-eluting stents in renal artery stenosis. Eur Radiol. 2008. 18:678–682.

9. Zähringer M, Sapoval M, Pattynama PM, Rabbia C, Vignali C, Maleux G, Boyer L, Szczerbo-Tojanowska M, Jaschke W, Hafsahl G, et al. Sirolimus-eluting versus bare-metal low-profile stent for renal artery treatment (GREAT Trial): angiographic follow-up after 6 months and clinical outcome up to 2 years. J Endovasc Ther. 2007. 14:460–468.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download