Abstract

A 29-yr-old man, presented with abdominal pain and fever, had an initial computed tomography (CT) scan revealing low attenuation of both adrenal glands. The initial concern was for tuberculous adrenalitis or autoimmune adrenalitis combined with adrenal hemorrhage. The patient started empirical anti-tuberculous medication, but there was no improvement. Enlargement of cervical lymph nodes were developed after that and excisional biopsy of cervical lymph nodes was performed. Pathological finding of excised lymph nodes was compatible to NK/T-cell lymphoma. The patient died due to the progression of the disease even after undergoing therapeutic trials including chemotherapy. Lymphoma mainly involving adrenal gland in the early stage of the disease is rare and the vast majority of cases that have been reported were of B-cell origin. From this case it is suggested that extra-nodal NK/T-cell lymphoma should be considered as a cause of bilateral adrenal masses although it is rare.

Primary extra-nodal lymphoma accounts for one-third of all lymphomas and often involves GI tract, head and neck, bone and skin, lung, and rarely adrenal glands (1). Secondary involvement of the adrenal gland with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL) has been reported to occur in up to 25% of NHL patients during the course of the disease (2). However, primary adrenal lymphoma (PAL) or lymphoma involving adrenal gland mainly in the early stage of disease is extremely rare. PAL may present with adrenal insufficiency, fever of unknown origin, or it can also be discovered incidentally on abdominal imaging (3, 4). The vast majority of previously reported cases of PAL or secondary involvement of the adrenal gland with NHL were of B-cell origin (1, 3-5).

Here, we report a case of natural killer (NK)/T-cell nasal type lymphoma mainly involving adrenal gland similar to PAL and it was diagnosed with delay due to mimicking adrenal hemorrhage.

A 29-yr-old man was admitted to our hospital after several weeks of lumbar pain and fever up to 38℃ on January 19, 2007. He had no significant past medical history. His vital signs were: blood pressure 130/80 mmHg, heart rate 121/min, and body temperature 38.2℃. Upon physical examination, there was no lymphadenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly. Laboratory tests revealed anemia (hematocrit (Hct) 31.8%, hemoglobin (Hb) 11.8 g/dL), white blood cell (WBC) 3.92 × 103/µL, elevated aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 78 IU/L and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 71 IU/L, and markedly elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) 1,591 IU/L. A computed tomography (CT) scan taken prior to admission revealed low attenuation of both adrenal glands, an indication of adrenal hemorrhage or acute adrenalitis (Fig. 1A). At that time, serum cortisol level was 17.47 µg/dL at 8 AM and ACTH level was 12.1 pg/mL (normal range: 10-90). Chest radiography taken at our emergency department showed left sided pleural effusion (Fig. 1B, C). Pleural fluid was aspirated and pleural needle biopsy showed that the fluid was exudate with lymphocyte predominance and the level of adenosine deaminase (ADA) was 93 IU/L (normal range: 4.3-20.3). Stain for acid-fast bacilli and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay on the pleural fluid was negative and pleural biopsy specimen was inadequate. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen suggested of adrenal hemorrhage or adrenalitis necessary for differential diagnosis of adrenal tuberculosis (Fig. 2). Therefore, the initial concern was for tuberculous pleurisy and tuberculous adrenalitis, or autoimmune adrenalitis combined with adrenal hemorrhage. The patient was started on empirical anti-tuberculous treatment, although there was no direct evidence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis due to the fever and his worsening condition. However, his fever and abdominal pain continued and there was no improvement in his conditin. Ten days after admission, pancytopenia (WBC 2.88 × 103/µL, Hb 10.7 g/dL, platelets 129 × 103/µL) developed. Bone marrow biopsy was negative for specific hematologic or malignant disorder. Another CT scan of the abdomen revealed an enlargement of the previous adrenal lesion which extended to the retroperitoneal space (Fig. 3). Twenty-two days after admission, explorative laparotomy targeting the adrenal lesion was performed and some tissue was obtained, which contained only necrotic debris. Despite conservative management, his condition deteriorated progressively. At that time, with a strong suspicion that he had a malignant disorder, positron emission tomography/CT (PET/CT) scan was taken and it revealed both adrenal gland and multiple cervical, mediastinal and abdominal lymph nodes with intense FDG uptake (Fig. 4). Therefore, a cervical lymph node was excised surgically after thirty eight days from admission. The pathologic finding was a monotonous arrangement of small tumor cells with positive nuclear staining with Ki-76 (MIB-1), and immunohistochemical staining was positive for CD45, CD30, and CD56 activity, but negative for CD20 activity (Fig. 5). These findings confirmed the diagnosis of non-Hodgkin T-cell lymphoma, natural killer (NK)/T-cell, nasal type. At last, he was referred to the hemato-oncology department and received combination chemotherapy of ifosfamide, mesothrexate, etoposide (IMVP-16) and prednisolone forty seven days after admission. Unfortunately, he could not receive further cycles of chemotherapy after first cycle of treatment because of postoperative wound infection and continuous fever. His disease was aggravated despite of the chemotherapy with conservative management, and finally he died on March 20, 2007, 59 days after his first admission.

Primary adrenal lymphoma (PAL) or lymphoma involving mainly adrenal gland without regional lymph node involvement in the early stage of the disease which is difficult to discriminate from PAL is a very rare extra-nodal lymphoma. Patients with adrenal lymphoma may present with local symptoms such as abdominal/lumbar pain or systemic symptoms including fever, fatigue, and weight loss (1, 3-5). Approximately 50% of patients with adrenal lymphoma including PAL experience symptoms of adrenal insufficiency such as vomiting, marked fatigue, skin pigmentation, and hypotension (5). On the other hand, PAL can be discovered incidentally on abdominal imaging (6-8). However, there is no pathognomic appearance on imaging studies to indicate lymphomatous involvement of the adrenal glands (5, 7). When adrenal masses are bilateral, several diagnoses including cortical adenoma, pheochromocytoma, metastatic disease, lymphoma, infection (e.g., tuberculosis, cryptococcosis etc.), bilateral adrenal hemorrhage, and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)-dependent Cushing's syndrome are considered (9, 10). Therefore, confirmative diagnosis of PAL is commonly established by image-guided percutaneous biopsy, surgical exploration, or postmortem examination (11-13). As the initial presentation of our patient's tumor in the adrenal gland similar as PAL is extremely rare, our first impression was tuberculous adrenalitis combined with hemorrhage rather than lymphoma mainly involving adrenal glands.

The definitive diagnosis of tuberculous pleural effusion depends on the demonstration of M. tuberculosis in the sputum, pleural fluid, or pleural biopsy specimens (14). The diagnosis can also be established with reasonable certainty by demonstrating granuloma in the parietal pleura or an elevated adenosine deaminase (ADA) level in pleural fluid in the adequate clinical context (15). The most widely accepted cutoff value for pleural fluid ADA is 40 U/L, and higher ADA level is associated with a greater chance of a patient having tuberculosis. Our patient's pleural fluid was exudate with lymphocyte predominance and ADA level was 93 IU/L. In addition to this pleural fluid finding, the regional characteristic of Korea that tuberculosis is quite popular guided us to make a wrong diagnosis.

Histopathologically, the most common type of PAL or lymphoma involving adrenal gland is diffuse large B-cell (1, 3-5). Although extranodal NK/T-cell lymphomas are more common in Asia, especially in Korea compared to Western countries (16), primary adrenal NK/T-cell lymphoma or massive adrenal involvement in the early course of diseases is extremely rare. On literature review, we found a few similar cases of NK/T-cell, nasal type lymphoma involving mainly adrenal gland and the information are listed in Table 1. Unlike upper aerodigestive tract NK/T-cell lymphoma, extra-upper aerodigestive tract NK/T-cell lymphomas are often multifocal and pursue an aggressive course (17).

Treatment options for PAL include surgery, combination chemotherapy, surgery followed by chemotherapy and radiotherapy (5). However, the optimal treatment for NK/T-cell lymphoma has not been established yet (18). Glucocorticoid replacement therapy is mandatory when adrenal insufficiency is present. The prognosis of PAL is very poor compared to that of other types of extra-nodal NHL; most follow-up studies showed that patients die of tumor, intercurrent disease or infection within 1 yr of diagnosis (5, 11, 12, 19). In our case, the patient was treated with combination chemotherapy of ifosfamide, mesothrexate, etoposide (IMVP-16). However, he could receive only one cycle of chemotherapy due to infectious complication and progression of the disease. At admission, there was no evidence of adrenal insufficiency on corticotropin simulation test. As time passes, subsequent test revealed adrenal insufficiency after admission; we started prednisolone for adrenal hormone supplementation. Eventually, he expired 59 days after admission, and 22 days after confirmative diagnosis. The rapid deterioration of our patient was similar to patients described in other studies.

NK/T-cell lymphoma is strongly associated with Epstein Barr virus (EBV), suggesting a pathogenic role for the virus (16, 20). In blood laboratory findings, any of the antibodies to antigen complex, including IgM anti-EBVCA (viral capsid antigen), IgM anti-EBEA (early antigen), and IgM EBNA (nuclear antigen) were not found. However, laboratory tests were not always foolproof. Unfortunately, we did not perform an analysis of EBV terminal repeat region from excised lymph node specimens. Therefore, we could not definitively conclude whether the patient's disease was associated with EBV infection or not.

We described the unusual case of adrenal NK/T-cell nasal type lymphoma diagnosed with delay due to mimicking adrenalitis with hemorrhage which was difficult in the discrimination from adrenal tuberculosis. Adrenal lymphoma, although PAL or dominantly adrenal gland involvement is rare, should be considered in the differential diagnosis for an adrenal mass. In addition, extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma also should be considered in Asian area.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Outside computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and chest radiography taken at admission. (A) CT scan reveals the enlargement surrounding both adrenal glands, especially left side and hyperattenuating fat (arrows) which is suggesting inflammatory condition or hemorrhage. On the chest radiographys, blunting of left costophrenic angle (arrowhead) on the posteroanterior view (B) and fluid shifting (arrowheads) in the left decubitus view (C) demonstrate the presence of pleural fluid in left pleural space. There is no abnormal consolidative or mass-like lesion in both lung fields.

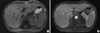

Fig. 2

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen. The enlargement surrounding both adrenal glands which is aggravated compared with the previous CT scan. The isosignal intensity on T1-weighted image (A) and subtle low signal intensity on T2-weighted image (B) around both adrenal glands suggest adrenal hemorrhage or adrenalitis such as adrenal tuberculosis.

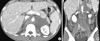

Fig. 3

Follow up CT scan of the abdomen. (A) The enlargement surrounding both adrenal glands with low attenuation which is more aggravated and extended to the retroperitoneal space compared with the previous CT scan and MRI. (B) The enlargement of multiple paraaortic lymph nodes which are not evident in the previous CT scan are detected on this study.

Fig. 4

Positron emission tomography (PET)/CT scan. Variable intensities of FDG uptake is detected in both adrenal glands and surrounding retroperitoneal space, and in the cervical, mediastinal and paraaortic lymph nodes.

Fig. 5

Pathological finding of surgically excised cervical lymph node. (A) The lymph node is well capsulated with marked degree of necrosis (H&E, × 100), (B) Neoplastic infiltrate of relatively pleomorphic lymphoid cells with scanty cytoplasm, irregular nuclear contour, and prominent nucleoli (H&E, × 400). Immunohistochemical staining demonstrate positive nuclear staining with Ki-67 (MIB-1) (C), and positive for CD45 (D), CD30 (E) and CD56 (F), but negative CD20 activity (G).

References

1. AlShemmari SH, Ameen RM, Sajnani KP. Extranodal lymphoma: a comparative study. Hematology. 2008. 13:163–169.

2. Rosenberg SA, Diamond HD, Jaslowitz B, Craver LF. Lymphosarcoma: a review of 1269 cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 1961. 40:31–84.

3. Mantzios G, Tsirigotis P, Veliou F, Boutsikakis I, Petraki L, Kolovos J, Papageorgiou S, Robos Y. Primary adrenal lymphoma presenting as Addison's disease: case report and review of the literature. Ann Hematol. 2004. 83:460–463.

4. Levy NT, Young WF Jr, Habermann TM, Strickler JG, Carney JA, Stanson AW. Adrenal insufficiency as a manifestation of disseminated non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Mayo Clin Proc. 1997. 72:818–822.

5. Grigg AP, Connors JM. Primary adrenal lymphoma. Clin Lymphoma. 2003. 4:154–160.

6. van den Heiligenberg SM, van Groeningen CJ. Bilateral adrenal enlargement with an unexpected diagnosis. Eur J Intern Med. 2007. 18:249–250.

7. Wang J, Sun NC, Renslo R, Chuang CC, Tabbarah HJ, Barajas L, French SW. Clinically silent primary adrenal lymphoma: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Hematol. 1998. 58:130–136.

8. Wang FF, Su CC, Chang YH, Pan CC, Tang KT, Jap TS, Lin HD, Won J. Primary adrenal lymphoma manifestating as adrenal incidentaloma. J Chin Med Assoc. 2003. 66:67–71.

9. Arora S, Vargo S, Lupetin AR. Computed tomography appearance of spontaneous adrenal hemorrhage in a pheochromocytoma. Clin Imaging. 2009. 33:314–317.

10. Nawar R, Aron D. Adrenal incidentalomas: a continuing management dilemma. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2005. 12:585–598.

11. Dunning KK, Wudhikarn K, Safo AO, Holman CJ, McKenna RW, Pambuccian SE. Adrenal extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma diagnosed by fine-needle aspiration and cerebrospinal fluid cytology and immunophenotyping: a case report. Diagn Cytopathol. 2009. 37:686–695.

12. Thompson MA, Habra MA, Routbort MJ, Holsinger FC, Perrier ND, Waguespack SG, Rodriguez MA. Primary adrenal natural killer/T-cell nasal type lymphoma: first case report in adults. Am J Hematol. 2007. 82:299–303.

13. Tomoyose T, Nagasaki A, Uchihara JN, Kinjo S, Sugaya K, Onaga T, Ohshima K, Masuda M, Takasu N. Primary adrenal adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Hematol. 2007. 82:748–752.

14. Gopi A, Madhavan SM, Sharma SK, Sahn SA. Diagnosis and treatment of tuberculous pleural effusion in 2006. Chest. 2007. 131:880–889.

15. Porcel JM. Tuberculous pleural effusion. Lung. 2009. 187:263–270.

16. Ko YH, Ree HJ, Kim WS, Choi WH, Moon WS, Kim SW. Clinicopathologic and genotypic study of extranodal nasal-type natural killer/T-cell lymphoma and natural killer precursor lymphoma among Koreans. Cancer. 2000. 89:2106–2116.

17. Lee J, Kim WS, Park YH, Park SH, Park KW, Kang JH, Lee SS, Lee SI, Lee SH, Kim K, Jung CW, Ahn YC, Ko YH, Park K. Nasal-type NK/T cell lymphoma: clinical features and treatment outcome. Br J Cancer. 2005. 92:1226–1230.

18. Kohrt H, Advani R. Extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma: current concepts in biology and treatment. Leuk Lymphoma. 2009. 50:1773–1784.

19. Mizoguchi Y, Nakamura K, Miyagawa S, Nishimura S, Arihiro K, Kobayashi M. A case of adolescent primary adrenal natural killer cell lymphoma. Int J Hematol. 2005. 81:330–334.

20. Kwong YL. Natural killer-cell malignancies: diagnosis and treatment. Leukemia. 2005. 19:2186–2194.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download