Abstract

This study aimed to develop a Korean version of the Type D Personality Scale-14 (DS14) and evaluate the psychiatric symptomatology of Korean cardiac patients with Type D personality. Healthy control (n = 954), patients with a coronary heart disease (n = 111) and patients with hypertension and no heart disease (n = 292) were recruited. All three groups completed DS14, the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (EPQ), the state subscale of Spielberger State and Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI-S), the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Short Depression Scale (CESD), and the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ). The Korean DS14 was internally consistent and stable over time. 27% of the subjects were classified as Type D. Type D individuals had significantly higher mean scores on the STAI-S, CESD, and GHQ compared to non-Type D subjects in each group. The Korean DS14 was a valid and reliable tool for identifying Type D personality. The general population and cardiovascular patients with Type D personality showed higher rate of depression, anxiety and psychological distress regarding their health. Therefore, identifying Type D personality is important in clinical research and practice in chronic medical disorders, especially cardiovascular disease, in Korea.

There have been many studies focusing on the role of psychosocial and behavioural factors such as depressive disorder, negative emotion and social isolation in cardiovascular disease (CVD). The construct of personality is also known to be associated with morbidity and mortality of coronary heart disease (CHD) as an independent predictor (1). One of the most well known personality constructs is type A behavioural pattern (TABP) which is characterised by aggressiveness, hostility, time-urgency, competitiveness and achievement striving (1). Although some studies with general populations or high risk groups have yielded a relationship between TABP and CHD (2, 3), it remains controversial whether TABP is a risk factor for CHD, because some studies have failed to show a contribution of TABP on CHD (4, 5) and others pointed to an association of the components of TABP such as hostility and anger with CHD (6, 7).

Another personality construct that recently received a lot of attention is the Type D personality construct. This discrete, homogeneous, distressed personality type was developed in European patients with ischemic heart disease. Type D personality is characterised by both normal and stable personality traits, negative affectivity (NA, the tendency to experience negative emotions) and social inhibition (SI, the tendency to inhibit expression of emotions) (8). Type D personality is associated with an increased risk of impaired quality of life, morbidity and mortality in conjunction with various CVDs (8). It has also been suggested as a prognostic predictor and a determinant of clinical outcome and health status, even after therapeutic interventions (9).

To assess this personality construct using a reliable and standardized method, Type D Personality Scale-14 (DS14) was developed. The validity and reliability of the DS14 has been established in European populations (10-12) and in China (13). However, its applicability has not yet been investigated in Korean subjects. The development of the Korean DS14 with proper psychometric properties would be useful in predicting the risk of CHD and prognosis in Korean clinical samples. In addition, the development of the Korean version of the DS14 will form the basis for future epidemiological and clinical studies of Type D personality in Korea.

The purpose of the current study was to develop a Korean version of the DS14 and to establish its validity and reliability based on the Korean general population and on cardiovascular patients. Furthermore, we examined the prevalence of the Type D construct and its psychological impact on these samples.

Personality Type D was assessed with the 14-item DS14, which measures NA and SI. Each item is rated according to a 5-point Likert scale from 0 (false) to 4 (true). Patients who score high on both NA and SI, as determined by using the cut-off of 10 on both scales, are classified as Type D. The Cronbach's alpha was 0.88 for the NA and 0.86 for the SI, respectively and test-retest reliability was 0.72 and 0.82 for the NA and SI, respectively in the original DS14 (10).

For the initial translation, three Korean psychiatrists and one bilingual Korean professional translated the English version of the DS14 into Korean. This was followed by a process of back translation and revisions. In the first pretest, some of the SI items did not adequately reflect SI domains. SI domain of the original DS14 consists of 5 items which reflect the low-order trait of reticence and 2 items which reflect the low-order trait of withdrawal. Thus 3 SI items which proved to reflect the low-order trait of withdrawal with a higher loading and corrected item-total correlation in the previous refining study (14), were added to the original 14 items in the following three pretests. Finally, a translation committee developed the preliminary 17-item Korean version of the DS14.

Consecutive patients with CHD or hypertension (HTN) without heart disease were recruited from July 2007 to December 2007 from the Korean University Ansan Hospital. Patients with CHD were recruited at admission for Percutaneous Transluminal Coronary Angioplasty (PTCA) due to unstable angina or acute myocardial infarction (MI). Patients were excluded if they suffered from other life-threatening diseases or cognitive impairments, had a history of psychiatric disorders, or were unable to understand and read Korean. A total of 293 patients with HTN and 111 with CHD were recruited in this study. We also included 988 healthy controls were recruited during the same time period among visitors who accompanied patients to various outpatient clinics of each participating hospitals in Seoul and Ansan, Ilsan in South Korea. Controls were excluded if they suffered from CHD, HTN or other life-threatening diseases or cognitive impairments, had a history of psychiatric disorders, or were unable to understand and read Korean.

Neuroticism and extroversion were assessed with the Korean 48-item short version of the EPQ (15). The Neuroticism and Extroversion subscales of the EPQ were included in the current study in order to examine the construct validity of the DS14 against these scales, since they measure theoretically similar constructs. Each of the subscales contains 12 items with dichotomous response categories 1 (yes) and 0 (no). The Cronbach's alpha of the Korean version was 0.78 for the Neuroticism subscale and 0.79 for the Extroversion subscale (15).

We investigated anxiety using the Korean version (16) of STAI-S to examine the extent to which DS14 scores were affected by the anxiety status of the subjects. The items of this subscale are answered on a 4-point Likert scale from 1 (not at all) to 4 (very much so). The Cronbach's alpha of the State Anxiety scale was 0.92 for the Korean version (16).

The CESD is a short self-report scale designed to measure depressive symptoms. To examine the extent to which DS14 scores were affected by mood status, the subjects completed the Korean version of the CESD (17). The CESD contains 20 items and each item is scored on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 to 3. The internal consistency of the Korean version was 0.89 (17).

To examine the extent to which DS14 scores were affected by quality of life, the subjects completed the GHQ. In the Korean version of GHQ, each item is scored on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 3 (18).

A research interview was conducted face-to-face to obtain screening information to identify potential control and patients groups. The control and HTN groups completed DS14 and the EPQ, the STAI-S, the CESD and the GHQ. These measures were also administered to the CHD group on admission for PTCA. To examine the stability of the DS14 scales, the CHD patients completed the questionnaires at 8 weeks in outpatient settings after PTCA.

Missing items were replaced with the mean of the completed items in each subscale. The number of missing values on each item was less than 1.5%. The chi-square test or the Fisher's exact test was used to examine between group differences on categorical variables. In order to evaluate the initial structure of each subscale and to determine which 7 out of 10 items could best be loaded onto the SI subscale, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was performed with the control group. The extraction method was principal axis factor analyses (PFA) with varimax rotation to maximize loadings and eliminate double loadings. The loading factor of 0.40 was selected as the item criteria. After determining the 14 items, the internal consistency of the DS14 subscales was assessed with Cronbach's alpha and item-total correlation.

To investigate the stability of factor structure, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) with the CVD patients (HTN and CHD patients) was conducted using the relative chi-squared index, the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), the Tucker Lewis Index (TLI), and the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) as goodness-of-fit indices. The relative chi-squared index of 5 or lower indicates an adequate model fit (19). An RMSEA of 0.08 or lower indicates an acceptable fit (20). Values above 0.90 on the TLI and CFI indicate a good model fit (20). Pearson's correlations were used to examine the construct validity of the Type D scale against the theoretically similar Neuroticism and Extroversion subscales of the EPQ. Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) in the CHD group were calculated to examine test-retest reliability with values of 0.61 to 0.80 denoting substantial agreement (21). In the CHD group, changes over 8 weeks in the measures were analysed by repeated measures MANOVA with measure and time as within-subjects factors and Type D as the between- subjects factor to investigate the psychological impact of Type D. All tests used were two-tailed. CFA was conducted using AMOS 4.0 and all other analyses were performed using SPSS 10.1.

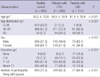

Prior to statistical analyses, 34 control subjects and one subject with HTN were excluded due to 11 or more missing responses on the questionnaires. Finally, 954 control subjects (356 males and 598 females), 292 HTN subjects (142 males and 150 females) and 111 CHD subjects (70 males and 41 females) were included in the analyses. The characteristics of each group are summarized in Table 1. There were significant differences among three groups in age, gender, education, and the number of participants living with spouse.

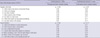

PFA with varimax rotation was conducted with the control group to determine the number of potential factors by the size of the eigenvalue, the variance explained and the Scree test. Based on the Scree plot, it was determined that two factors, representing approximately 47.4% of the total variance would be interpreted. Based on these findings, PFA were conducted specifying two factors with varimax rotation. However, some of the original SI items failed to contribute meaningfully to the SI construct. Therefore, two of original SI items and one of the additional items were deleted based on the limited importance of these items in the SI construct and statistical results. The analyses were conducted again with these items removed, and the results are described in Table 2. The new two-factor solution accounted for 51.9% of the total variation, with eigenvalues of 5.9 and 1.3 respectively for the first two factors. NA items had a loading ranging from 0.52 to 0.78 and the newly selected SI items had a loading ranging from 0.42 to 0.70 on their corresponding trait factor (Table 2).

After screening the seven items of the SI construct, an internal consistency reliability analysis was conducted on each subscale. The Cronbach's alpha was 0.86 for NA and 0.80 for SI, suggesting a high degree of internal consistency. The correlation coefficients between each item and the total score of NA and SI ranged from 0.52 to 0.69 and from 0.44 to 0.61, respectively. Based on these data, it can be concluded that both subscales are internally consistent and have good content validities.

The predicted measurement model resulting from the EFA, with 14 observed and 2 latent variables, was validated using CFA with the CVD patients. The maximum likelihood method was used to estimate the level of data fit to the model. Results of the CFA are also presented in Table 2, including factor loadings and coefficient alpha. NA items had a loading ranging from 0.58 to 0.77 and the SI items had a loading ranging from 0.34 to 0.71 and coefficient alpha was 0.87 for NA and 0.77 for SI. The results also included a relative chi-squared index of 3.40, thus indicating adequate absolute fit of the model with the data. In addition, RMSEA of 0.077 indicated an acceptable model fit and the TLI of 0.90 and the CFI of 0.92 also indicated that the model fit the data, with each meeting the 0.90 criterion for good model fit.

NA correlated positively with the neuroticism (r = 0.63, P < 0.001) and SI negatively with the extraversion subscale (r = -0.61, P < 0.001) of the EPQ in the control group. In the HTN group, the NA also yielded a high correlation with the neuroticism (r = 0.74, P < 0.001) and SI yielded a negative correlation with the extraversion subscale (r = -0.55, P < 0.001). In the CHD group, the results were similar: for NA with the neuroticism, r = 0.68, P < 0.001; for SI with the extraversion, r = -0.61, P < 0.001. This finding suggests that the DS14 has good concurrent validity and that NA and SI are related with neuroticism and extraversion respectively, but not identical to them. The 8-week test-retest reliability in the CHD group was good, with an ICC of 0.76 for NA and that of 0.77 for SI.

Using the original version's cut-off of 10 on both DS14 subscales, 27.0% of the subjects were classified as Type D. In addition, no significant difference was shown between male (27.3%) and female groups (26.7%). There was no significant difference among the general population, the HTN group, and the CHD group (27.8%, 24.7% and 26.1%, respectively). An age-restricted subgroup (over 40 yr; mean, 54.86 ± 9.17) also did not show significant differences among the three groups or between male and female groups. The demographic characteristics of Type D and non-Type D subjects in each group are summarized in Table 3.

Compared to non Type D subjects, Type D individuals had significantly higher symptom levels of anxiety, depression and general distress (Fig. 1). In the control group, Type D subjects showed a significant higher score on the STAI-S, CESD, and GHQ compared to non Type D subjects: STAI-S for Type D subjects, 36.5 ± 26.3 and for non Type D subjects, 26.3 ± 8.0 (P < 0.001); CESD for Type D subjects, 16.0 ± 10.2 and for non Type D subjects, 7.3 ± 6.5 (P < 0.001); GHQ for Type D subjects, 17.1 ± 5.6 and for non Type D subjects, 11.7 ± 5.7 (P < 0.001). In the HTN group, Type D subjects also showed a significant higher score on the measures compared to non Type D subjects: STAI-S for Type D subjects, 39.6 ± 8.89 and for non Type D subjects, 25.0 ± 7.9 (P < 0.001); CESD for Type D subjects, 19.6 ± 11.7 and for non Type D subjects, 6.1 ± 6.4 (P < 0.001); GHQ for Type D subjects, 17.3 ± 6.5 and for non Type D subjects, 9.9 ± 5.5 (P < 0.001). In the CHD group, the results were similar: STAI-S for Type D subjects, 38.1 ± 8.9 and for non Type D subjects, 29.3 ± 7.9 (P < 0.001); CESD for Type D subjects, 21.2 ± 10.7 and for non Type D subjects, 10.7 ± 7.9 (P < 0.001); GHQ for Type D subjects, 17.7 ± 5.5 and for non Type D subjects, 14.2 ± 8.1 (P = 0.02).

In the CHD group, repeated-measures MANOVA indicated that there were significant main group effects of Type D personality on these anxiety, depression and general distress levels: STAI-S, P < 0.001; CESD, P < 0.001; GHQ, P = 0.01. In addition, as within-subjects factors indicated that NA, SI, and GHQ did not significantly change over time while depression and anxiety significantly changed: CESD, P = 0.026; STAI-S, P = 0.049. These results confirm the temporal stability of the DS14 without being affected by depression and anxiety over the course of 8 weeks.

In this study, a Korean version of the DS14 for Type D personality was successfully developed. The Type D personality construct was found to be applicable to Koreans, with the results suggesting a psychological impact of the Type D personality construct on CHD patients. The Korean version of the DS14 showed good internal consistency, construct validity, concurrent validity and time stability. Although two original items were replaced with other items that were introduced in a previous study (14), this study revealed that the Korean version of the DS14 has good model fit and is more reliable and valid than the original version of the DS14 in the Korean setting. The differences with these items may possibly be due, in part, to problems in the translation of the original DS14 or to problems related to cultural differences. Asian cultures nurture the collectivistic values that foster a sense of interdependence with others, whereas Western cultures tend toward broad socialization that encourages individualism and independence (22). Furthermore, shy and inhibited behaviours are less likely to be regarded as maladaptive in Asian cultures and may be positively valued and encouraged (23). For these reasons, some SI items may be unfamiliar to Koreans and Koreans seemed to provide responses to these items that were different from those of Westerners.

The current study showed that the prevalence of Type D personality in the general population and patients with CHD was 27.8% and 26.1%, respectively. In previous research, the prevalence of Type D personality was 13.3%-38.5% in the general population or healthy controls (10-13, 24), whereas it was 14%-35.9% in the CHD population (10-13, 25). A validation study of DS14 showed that Type D was more prevalent in the CHD group and HTN group than the general population in the Belgium setting (10). A Hungarian study also showed that Type D is a predictor of CVD after controlling for sex and age (25). However, the prevalence of Type D personality among Chinese CHD patients (31.4%) was similar to that among Chinese healthy subjects (31.9%) (13). Moreover, in a German sample, the prevalence rates of the Type D pattern were lowest in cardiological patients (25%), whereas they were 32.5% in healthy factory workers (11). These inconsistent findings may be due to different sample characteristics such as age and sex proportion and influences of other behavioural risk factors for CHD such as diet, exercise, tobacco use, heavy use of alcohol, diabetes and obesity. In addition, severity of cardiovascular symptoms or cardiac dysfunction was not considered as a confounding factor in these studies. Our sample includes all patients who were admitted into the hospital for PTCA due to unstable angina or acute MI, whereas the validation study of the original version DS14 recruited patients suffering from a first and acute MI (10). These issues are important for additional studies to identify how the Type D construct contributes to the incidence or progression of CHD. Another important factor is the cultural and ethnic differences among the subjects of these studies. Modesty as well as inhibited behaviour has been encouraged in Korea and Koreans tend to avoid an overt expression of their emotions or thoughts. These response styles may affect the scores on both the NA and SI subscales. Therefore, using the original version's cut-off of 10 may contribute to the differences in the observed prevalence of Type D and further studies must determine the cut-off point of both DS14 subscales considering cross-cultural differences.

Our study showed that Type D subjects scored higher on anxiety and depressive symptoms scales compared to non-Type D subjects in both the general population and CVD patients. Furthermore, Type D patients with CHD exhibited more severe anxiety and depression than non-Type D patients with CHD after PTCA. Depression and anxiety impacts the outcome of coronary bypass surgery (26). In addition, some studies showed that these are also adverse prognostic factors for patients with acute MI (27, 28). Although our study did not find an etiological role of Type D personality in cardiovascular disease, these studies suggested that Type D personality may affect the health outcome of CHD via depression and/or anxiety. It has been reported that Type D individuals have higher cortisol reactivity (29) and higher proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α (30) which are associated with depression and anxiety. While these biological findings may results from chronic medical disorders via immune activation or inflammation, and/or vulnerability to disease-induced stress, they partially explain why Type D personality may predict an adverse effect on prognosis of CHD. Therefore, considering the prognostic role of negative emotions, the relationship of Type D personality with them may have important clinical implications in both psychopharmacological and psychotherapeutic interventions of CHD. Interestingly, this study also showed that depression and anxiety were higher in the Type D group than the non-Type D group of the general population. Although the Type D personality conceptually overlaps with negative emotions such as dysphoria and anxiety, considering the time stability of this personality construct, Type D could be expected to be a psychosocial risk factor of depression and anxiety in the general population as well as in patients with non-cardiovascular medical disorders. Therefore, future studies must be conducted to investigate the impact of Type D personality on the psychological aspect and clinical course of various medical disorders.

The limitations of the present study are its cross-sectional nature and relatively small sample size. In addition, the finding of test-retest reliability was somewhat limited by the small sample size of the CHD group. This hospital-based study resulting in differences in demographic variables among groups may limit the statistical power and the generalizability of results. Finally, this study utilized self-rating scales or self-reported data that prevented controlling for the effects of underlying medical disorders or other psychopathology. However, this is the first study to show that the DS14 is applicable to the Korean setting with good validity and reliability.

These findings suggest that the Type D personality construct can be generalised to Koreans, even though the cultural background differs from that of the original version. Although the prevalence of Type D personality in the cardiovascular group was somewhat different from that in Western reports, the general population and cardiovascular patients with Type D personality showed higher rates of depression, anxiety, and psychological distress to their health. Therefore, identifying Type D personality is important for clinical research and practice in patients with chronic medical disorders, especially cardiovascular disease, in Korea.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Mean scores on the measures compared between Type D and non-Type D. Standard deviations are presented on top of bars, *P < 0.001; †P < 0.05. CESD, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Short Depression Scale; STAI-S, Spielberger State and Trait Anxiety Inventory-state; GHQ, General Health Questionnaire/Quality of Life -12; CHD, coronary heart disease; HTN, hypertension. |

AUTHOR SUMMARY

Assessment of the Type D Personality Construct in the Korean Population: A Validation Study of the Korean DS14

Hong Euy Lim, Moon-Soo Lee, Young-Hoon Ko, Young-Min Park, Sook-Haeng Joe, Yong-Ku Kim, Changsu Han, Hwa-Young Lee, Susanne S Pedersen, and Johan Denollet

This study aimed to develop a Korean version of the Type D Personality Scale-14 (DS14) and evaluate the psychiatric symptomatology of Korean cardiac patients with Type D personality. Healthy control (n = 954), patients with a coronary heart disease (n = 111) and patients with hypertension and no heart disease (n = 292) were recruited. All three groups completed DS14, the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (EPQ), the state subscale of Spielberger State and Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI-S), the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Short Depression Scale (CESD), and the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ). The Korean DS14 was internally consistent and stable over time. 27% of the subjects were classified as Type D. Type D individuals had significantly higher mean scores on the STAI-S, CESD, and GHQ compared to non-Type D subjects in each group. Identifying Type D personality is important in clinical research and practice in chronic medical disorders, especially cardiovascular disease.

References

1. Heilbrun AB Jr, Friedberg EB. Type A personality, self-control, and vulnerability to stress. J Pers Assess. 1988. 52:420–433.

2. Rosenman RH, Brand RJ, Jenkins D, Friedman M, Straus R, Wurm M. Coronary heart disease in Western Collaborative Group Study. Final follow-up experience of 8 1/2 years. JAMA. 1975. 233:872–877.

3. Haynes SG, Feinleib M. Type A behavior and the incidence of coronary heart disease in the Framingham Heart Study. Adv Cardiol. 1982. 29:85–94.

4. Case RB, Heller SS, Case NB, Moss AJ. Type A behavior and survival after acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1985. 312:737–741.

5. Cohen JB, Reed D. The type A behavior pattern and coronary heart disease among Japanese men in Hawaii. J Behav Med. 1985. 8:343–352.

6. Dembroski TM, MacDougall JM, Williams RB, Haney TL, Blumenthal JA. Components of Type A, hostility, and anger-in: relationship to angiographic findings. Psychosom Med. 1985. 47:219–233.

7. Barefoot JC, Dahlstrom WG, Williams RB Jr. Hostility, CHD incidence, and total mortality: a 25-year follow-up study of 255 physicians. Psychosom Med. 1983. 45:59–63.

8. Denollet J, Sys SU, Brutsaert DL. Personality and mortality after myocardial infarction. Psychosom Med. 1995. 57:582–591.

9. Pedersen SS, Denollet J, Ong AT, Sonnenschein K, Erdman RA, Serruys PW, van Domburg RT. Adverse clinical events in patients treated with sirolimus-eluting stents: the impact of Type D personality. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2007. 14:135–140.

10. Denollet J. DS14: Standard assessment of negative affectivity, social inhibition, and Type D personality. Psychosom Med. 2005. 67:89–97.

11. Grande G, Jordan J, Kummel M, Struwe C, Schubmann R, Schulze F, Unterberg C, von Kanel R, Kudielka BM, Fischer J, Herrmann-Lingen C. Evaluation of the German type D scale (DS14) and prevalence of the type D personality pattern in cardiological and psychosomatic patients and healthy subjects. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol. 2004. 54:413–422.

12. Pedersen SS, Denollet J. Validity of the Type D personality construct in Danish post-MI patients and healthy controls. J Psychosom Res. 2004. 57:265–272.

13. Yu XN, Zhang J, Liu X. Application of the Type D Scale (DS14) in Chinese coronary heart disease patients and healthy controls. J Psychosom Res. 2008. 65:595–601.

14. Denollet J. Type D personality. A potential risk factor refined. J Psychosom Res. 2000. 49:255–266.

15. Lee HS. The Mannual of Eysenck Personality Questionnaire. 2004. Seoul: Hakjisa;7–32.

16. Hahn DW, Lee CH, Chon KK. Korean adaptation of Spielberger's STAI (K-STAI). Korean J Health Psychol. 1996. 1:1–14.

17. Cho MJ, Kim KH. Use of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) Scale in Korea. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1998. 186:304–310.

18. Kook SH, Son CN. A validation of GHQ/QL-12 to assess the quality of life in patients with schizophrenia: using RMSEA, ECVI, and Rasch Model. Korean J Clin Psychol. 2000. 19:587–602.

19. Kline RB. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. 1998. New York: Guilford Press;189–242.

20. Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling. 1999. 6:1–55.

21. Kramer MS, Feinstein AR. Clinical biostatistics. LIV. The biostatistics of concordance. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981. 29:111–123.

22. Rubin KH. Social and emotional development from a cultural perspective. Dev Psychol. 1998. 34:611–615.

23. Heinrichs N, Rapee RM, Alden LA, Bögels S, Hofmann SG, Oh KJ, Sakano Y. Cultural differences in perceived social norms and social anxiety. Behav Res Ther. 2006. 44:1187–1197.

24. Williams L, O'Connor RC, Howard S, Hughes BM, Johnston DW, Hay JL, O'Connor DB, Lewis CA, Ferguson E, Sheehy N, Grealy MA, O'Carroll RE. Type-D personality mechanisms of effect: the role of health-related behavior and social support. J Psychosom Res. 2008. 64:63–69.

25. Kopp M, Skrabski A, Csoboth C, Rethelyi J, Stauder A, Denollet J. Type D personality: cross-sectional associations with cardiovascular morbidity in the Hungarian population. Psychosom Med. 2003. 65:A64.

26. Pignay-Demaria V, Lespérance F, Demaria RG, Frasure-Smith N, Perrault LP. Depression and anxiety and outcomes of coronary artery bypass surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003. 75:314–321.

27. van Melle JP, de Jonge P, Spijkerman TA, Tijssen JG, Ormel J, van Veldhuisen DJ, van den Brink RH, van den Berg MP. Prognostic association of depression following myocardial infarction with mortality and cardiovascular events: a meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. 2004. 66:814–822.

28. Rozanski A, Blumenthal JA, Kaplan J. Impact of psychological factors on the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease and implications for therapy. Circulation. 1999. 99:2192–2217.

29. Whitehead DL, Perkins-Porras L, Strike PC, Magid K, Steptoe A. Cortisol awakening response is elevated in acute coronary syndrome patients with type-D personality. J Psychosom Res. 2007. 62:419–425.

30. Denollet J, Vrints CJ, Conraads VM. Comparing Type D personality and older age as correlates of tumor necrosis factor-alpha dysregulation in chronic heart failure. Brain Behav Immun. 2008. 22:736–743.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download