Abstract

The safety of accelerated schedules of allergen immunotherapy (ASAI) in patients with bronchial asthma (BA) has been reported but there are little data on the safety of ASAI for patients with atopic dermatitis (AD). In this study, we investigated the safety of ASAI in patients with AD. Sixty patients with AD and 18 patients with BA sensitized to house dust mites (HDM) were studied. A maximum maintenance dose of HDM extract, adsorbed to aluminum hydroxide, was administered to patients by subcutaneous injection with either a 3-day protocol (rush immunotherapy) or 1-day protocol (ultra-rush immunotherapy). Systemic reactions were observed 4 of 15 patients (26.7%) with AD during rush immunotherapy, 13 of 45 patients (28.9%) with AD during ultra-rush immunotherapy, and 4 of 18 patients (22.2%) with BA during rush immunotherapy (P > 0.05). No severe or near fatal systemic reactions occurred in 78 subjects of this study. Systemic reactions developed within 4 hr after administration of the maximum allergen dose in 20 of 21 patients (95.2%) with AD and BA who showed systemic reactions during rush or ultra-rush immunotherapy. In conclusion, ASAI was safe and well tolerated in patients with AD. ASAI can be a useful therapeutic option for AD.

Allergen immunotherapy is a treatment of administering gradually increasing doses of allergen in order to decrease a hypersensitivity to the allergen and thereby reduce clinical symptoms from exposure to the allergen (1). The clinical efficacy of allergen immunotherapy has been proven for the treatment of allergic rhinitis (AR), bronchial asthma (BA), and Hymenoptera hypersensitivity (1, 2). It can alter the natural history of respiratory allergic diseases, prevent the development of new allergen sensitizations, and produce a sustained clinical improvement after discontinuation of treatment (2).

Despite various benefits of allergen immunotherapy, clinical application has been limited by the risk of severe allergic reactions and inconvenience of frequent hospital visits during the initial build-up phase of treatment (3). In a traditional schedule of allergen immunotherapy, weekly injections of increasing doses of allergen extract are required for about 12-16 weeks (initial build-up phase) to reach a maximum maintenance dose of allergen. The schedule is then changed to monthly injections of maintenance dose for 3-5 yr (3). The inconvenience of requiring frequent hospital visits during the initial build-up phase is one of the main reasons limiting a wider application of allergen immunotherapy in clinical practice. To overcome this inconvenience, accelerated schedules of allergen immunotherapy (ASAI) have been developed whereby the initial build-up phase is completed within 1-3 days (rush immunotherapy) (3). The use of rush immunotherapy has been suggested to provide a better compliance and a faster onset of clinical benefits during allergen immunotherapy (3). However, the rush immunotherapy could be associated with an increased incidence of systemic reactions (27%-100%) compared to the traditional schedule of allergen immunotherapy (0.84%-46.7%) and requires a use of hospital facilities to closely monitor patients for systemic reactions (3). The incidence of systemic reactions from rush immunotherapy can be reduced by the use of premedications including antihistamines and corticosteroids (4).

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a common, chronic relapsing inflammatory skin disease characterized by intense itching, dry skin, inflammation, and exudation (5). Inhalation or direct skin contact of house dust mite (HDM) allergens can exacerbate AD in patients with hypersensitivity to HDM (6, 7). Significant clinical improvement has been observed in patients with AD and hypersensitivity to HDM by reducing exposure to HDM allergens (8). These evidences strongly suggest an important pathogenic role of allergic responses to HDM in patients with AD and hypersensitivity to HDM.

An increasing amount of evidence has been reported on the clinical efficacy of allergen immunotherapy for the treatment of AD (9). Allergen immunotherapy with HDM extract has been proven to be clinically beneficial in patients with severe AD in a randomized controlled study (10). Although there are controversial issues on the clinical usefulness of allergen immunotherapy in the management of AD, AD sensitized to aeroallergen has been suggested as a potential indication for allergen immunotherapy in the recently published clinical practice parameter (11).

There have been numerous data on the safety of ASAI in patients with BA or AR (3). However, there have been little published data on the application of ASAI for patients with AD. We hypothesized that ASAI could be a safe therapeutic option in patients with AD as well as in patients with BA. In this study, we evaluated the safety of ASAI in patients with AD and hypersensitivity to HDM.

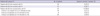

Sixty patients with AD and 18 patients with BA were studied (Table 1). All patients were over 12 yr of age. Patients with AD showed typical clinical features compatible with the diagnostic criteria of Hanifin and Rajka (12). All subjects with BA had a typical clinical history and either a 20% decrease in forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) following the inhalation of less than 8 mg methacholine/mL, or a documented reversibility of FEV1 greater than 15% after inhalation of a bronchodilator. Patients showed positive skin reactions (mean wheal diameter ≥ 3 mm over the saline control) to two kinds of HDM extract (Dermatophagoides farinae and Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus; Allergopharma Joachim Ganzer KG, Reinbeck, Germany) on the skin prick test and positive results on serum-specific IgE antibody tests to HDM (≥ 0.7 kU/L) by CAP-FEIA (Phadia, Uppsala, Sweden). Inclusion and exclusion criteria of patients for allergen immunotherapy in this study were consistent with the WHO and EAACI position papers for allergen immunotherapy (1, 13). Patients with AD were on standard therapeutic regimens including topical moisturizers, topical corticosteroids, and/or topical calcineurin inhibitors for more than 3 months, and their clinical symptoms were not effectively controlled. Patients with BA received appropriate medications including inhaled corticosteroids, bronchodilators, and leukotriene antagonists according to an international guideline for the management of BA (14).

The study was designed as an open-label non-randomized observational study to assess the safety of ASAI with HDM extract in patients with AD and BA.

HDM allergen extract containing a mixture of D. farinae and D. pteronyssinus extracts (50%:50%) adsorbed to aluminum hydroxide (Novo-Helisen Depot®; Allergopharma Joachim Ganzer KG, Reinbeck, Germany) was used for allergen immunotherapy. Biological potency of the HDM extract for maintenance immunotherapy was 5000 therapeutic units/mL according to the manufacturer. The HDM allergen extract was composed of three vials (labeled as No. 1, 2, and 3) containing three different concentrations of allergen with tenfold increases in concentration between each vial. The manufacturer recommends subcutaneous administration of increasing doses (0.1, 0.2, 0.4, and 0.8 mL of each vial) of HDM allergen extract each week for 12 weeks, and then 0.8 mL of the highest allergen concentration (vial No. 3) once a month as maintenance therapy.

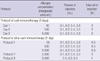

All patients received premedications consisting of fexofenadine 120 mg/day and ebastine 10 mg/day for at least 7 days prior to and during the immunotherapy. For accelerated schedules of allergen immunotherapy, patients were admitted to the hospital and received intravenous administration of normal saline to achieve vascular access during treatment. The schedules for subcutaneous injections of HDM extract during rush immunotherapy (3-day protocol) and ultra-rush immunotherapy (1-day protocol) are shown in Table 2. The ultra-rush immunotherapy was performed using three different protocols according to the injection intervals and the maximum allergen doses of HDM extract (Table 2). All patients were observed for over 16 hr (overnight) after administration of the maximum allergen dose prior to discharge from the hospital.

To assess safety, details of systemic reactions, doses of administered allergen, and onset time of systemic reactions were recorded. Severity of systemic reaction was graded according to the EAACI criteria for the classification of systemic reactions associated with allergen immunotherapy as previously reported (15, 16).

Incidence of systemic reaction was presented in absolute numbers and percentages. Kruskal-Wallis test or Mann-Whitney U test was used for comparisons of baseline characteristics of patients (age, total IgE, and specific IgE) between the groups. The chi-square test was used to compare incidences of systemic reactions between study groups, and a P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

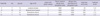

Systemic reactions were observed 4 of 15 patients (26.7%) with AD during rush immunotherapy, 13 of 45 patients (28.9%) with AD during ultra-rush immunotherapy, and 4 of 18 patients (22.2%) with BA during rush immunotherapy (Table 3). No significant difference was observed in the incidence of systemic reactions among the three groups (P > 0.05) (Table 3). During ultrarush immunotherapy in patients with AD, systemic reactions were observed in 6 of 16 patients (37.5%) with AD receiving 12 injections at 0.5-hr intervals, 2 of 9 patients (22.2%) with AD receiving 4 injections at 2-hr intervals, and 5 of 20 patients (25.0%) with AD receiving three injections at 1-hr intervals with a 50% reduced maximal allergen dose (Table 3). No significant difference was observed in the incidence of systemic reactions among the three groups (P > 0.05).

Seventeen of the 60 patients with AD (28.3%) showed systemic reactions during rush or ultra-rush immunotherapy. Localized or generalized urticaria was observed in 16 patients (26.7%) and mild bronchospasm (mild dyspnea without wheezing) was seen in 3 patients (5.0%) among 60 patients with AD during rush or ultra-rush immunotherapy (Table 4).

Four of the 18 patients with BA (22.2%) showed systemic reactions during rush immunotherapy. Localized or generalized urticaria was observed in 3 patients (16.7%) and moderate bronchospasm (moderate dyspnea with mild wheezing) in one patient (5.6%) during rush immunotherapy (Table 5).

Severity grades of systemic reactions associated with rush or ultra-rush immunotherapy were compatible with grade 1 or grade 2 according to the EAACI criteria for the classification of systemic reactions associated with allergen immunotherapy (Tables 4, 5). No severe or near fatal systemic reactions (grade 3 or grade 4 of EAACI criteria) occurred in 78 subjects of this study. All systemic reactions resolved rapidly following intravenous administration of 4 mg of chloropeniramine and 5 mg of dexamethasone for urticaria or inhalation of 200 µg of salbutamol for bronchospasm.

Fifty-eight patients with AD received the planned maximal dose of allergen according to the schedules for rush or ultra-rush immunotherapy. However, 50& of the maximal planned dose was administered in two patients with AD due to the development of systemic reactions (Table 4). All 18 patients with BA received the planned maximal dose of allergen (Table 5).

Systemic reactions developed within 4 hr after administration of the maximal allergen dose in 20 of 21 patients (95.2%) with AD and BA who showed systemic reactions during rush or ultra-rush immunotherapy (Tables 4, 5). Generalized urticaria was observed at 9 hr after administration of the planned maximal dose of allergen in one patient with AD during rush immunotherapy (Table 4).

In this study, ASAI using HDM extract were safe and tolerable in patients with AD. Incidence of systemic reactions during rush or ultra-rush immunotherapy using HDM extract was not significantly different in patients with AD (28.3%) compared to those with BA (22.2%). These results seem to be similar or a little bit lower than the incidences of systemic reactions (27%-100%) of previous studies in patients with BA and/or AR during rush immunotherapy using inhalant allergen extracts (3). This suggests that ASAI could be a safe therapeutic option for patients with AD.

We used an aluminum hydroxide adsorbed HDM extract for rush or ultra-rush immunotherapy in this study. A previous study reported that an overall cumulative incidence of systemic reactions during conventional schedule of allergen immunotherapy for 5 yr using unmodified soluble HDM extract was 43.75% in the patients with both AR and AD, and was significantly higher than 2.82% in patients with AR without AD (17). Systemic reactions occurred significantly more frequently in patients who received allergen immunotherapy with aqueous extract than those with aluminum hydroxide adsorbed extract of honeybee venom (18). We speculate that the use of aluminum hydroxide adsorbed HDM extracts reduced the incidence of systemic reactions in patients with AD during ASAI in this study.

Traditionally, aqueous allergen extract was preferentially used for rush immunotherapy instead of aluminum hydroxide adsorbed allergen extract (19). Aluminum hydroxide adsorbed allergen extract has an advantage of slower systemic release of allergen from the injection site compared to aqueous allergen extract (19). However, this characteristic of aluminum hydroxide adsorbed allergen extract could be associated with delayed onset of systemic reactions compared to aqueous allergen extract (19). In a previous report on the timing of onset of systemic reactions in 1,038 patients during allergen immunotherapy using aluminum hydroxide adsorbed allergens (mites, pollens, cat, and wasp and bee venoms) for 3 yr showed that 341 patients (33%) experienced systemic reactions and 94% of the systemic reactions were developed within 12 hr after injection of allergen extract (20). In our study, the systemic reaction was developed within 4 hr after administration of the maximum allergen dose in 95% of patients with AD and patients with BA during rush or ultra-rush immunotherapy. This suggests that ASAI with aluminum hydroxide adsorbed unmodified HDM allergen can be performed in patients with AD in an outpatient clinic setting with appropriate observation time after administration of the maximum allergen dose.

In this study, we tried three different protocols of ultra-rush immunotherapy in patients with AD and systemic reactions were observed in 37.5% of patients receiving 12 injections at 0.5-hr intervals, 22.2% of patients receiving four injections at 2-hr intervals, and 25.0% of patients receiving three injections at 1-hr intervals with a 50% reduced maximum allergen dose. Although no statistically significant difference in incidence of systemic reactions was observed among the three groups, incidence of systemic reactions seemed to be increased in patients with AD who received a maximum allergen dose with shorter intervals in this study. When we extrapolate retrospectively from the results of this study, a protocol administrating HDM extract by three subcutaneous injections at 2-hr intervals with a 50% reduced maximum allergen dose may be a safer protocol for ultra-rush immunotherapy in patients with AD and patients with BA.

Several trials have been conducted to reduce systemic reactions during ASAI (3). Premedication with antihistamines and systemic corticosteroids decreased the incidence of systemic reactions during rush immunotherapy in patients with AR and BA by approximately 50% (4). Pretreatment with anti-IgE monoclonal antibody (omalizumab) resulted in a fivefold decrease in the risk of anaphylaxis during rush immunotherapy with aqueous ragweed extracts in patients with seasonal AR (21). Recently, a study on ultra-rush immunotherapy using aluminum hydroxide adsorbed modified allergen (depigmented and polymerized) reaching the maintenance allergen dose on the first day with two injections at 0.5-hr intervals showed very low incidence of systemic reaction (0.75% of 1,068 patients) in patients with respiratory allergic diseases without the need of hospitalization or premedication (22). The use of various combinations of these approaches might further decrease the incidences of systemic reactions during ASAI in patients with AD.

The management of severe AD is a challenging issue for clinicians (23). Although oral corticosteroids, cyclosporin A, and mycophenolate mofetil are effective for the treatment of severe AD, the possibility of systemic toxicity from long-term treatment with these drugs limits their widespread use (23). A recent randomized controlled study on the clinical efficacy of allergen immunotherapy suggests that it can be a useful therapeutic option for patients with severe AD sensitized to HDM (10). However, a compliance rate of the study was approximately 50% at the end of the 1-yr treatment period. This relatively low compliance rate seems to be related to the weekly injection interval for 1 yr in the study (10). This is also seen for traditional schedules of allergen immunotherapy in patients with respiratory allergic disease whereby compliance at 1 yr was reported to be 46%-59% (24). Application of ASAI in the treatment of patients with respiratory allergic diseases has been suggested to increase compliance by reducing time and cost for hospital visits and providing a rapid onset of clinical efficacy (3). Interestingly, rush immunotherapy has been successfully tried in dogs and cats with AD without severe systemic reactions (25, 26). Further studies on the long-term safety and clinical efficacy are needed to evaluate a clinical usefulness of ASAI in patients with AD.

In conclusion, rush or ultra-rush immunotherapy was safe and well tolerated in patients with AD. ASAI can be a useful therapeutic option for AD.

Figures and Tables

Table 1

Characteristics of patients with atopic dermatitis (AD) or bronchial asthma (BA) who received rush or ultra-rush immunotherapy (ITx)

Table 3

Incidences of systemic reactions in patients with atopic dermatitis (AD) or bronchial asthma (BA) during rush or ultra-rush immunotherapy (ITx)

AUTHOR SUMMARY

Safety of Accelerated Schedules of Subcutaneous Allergen Immunotherapy with House Dust Mite Extract in Patients with Atopic Dermatitis

Myoung-Eun Kim, Jeong-Eun Kim, Joon-Mo Sung, Jin-Woo Lee, Gil-Soon Choi and Dong-Ho Nahm

The safety of accelerated schedules of allergen immunotherapy (ASAI) in patients with bronchial asthma has been reported but there are little data on their safety for patients with atopic dermatitis. In this study, we investigated the safety of ASAI in patients with atopic dermatitis and bronchial asthma sensitized to house dust mites. In summary, ASAI was safe and well tolerated in patients with atopic dermatitis, suggesting that ASAI can be a useful therapeutic option for atopic dermatitis.

References

1. Bousquet J, Lockey R, Malling HJ. Allergen immunotherapy: therapeutic vaccines for allergic diseases. A WHO position paper. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998. 102:558–562.

2. Pipet A, Botturi K, Pinot D, Vervloet D, Magnan A. Allergen-specific immunotherapy in allergic rhinitis and asthma. Mechanisms and proof of efficacy. Respir Med. 2009. 103:800–812.

3. Cox L. Accelerated immunotherapy schedules: review of efficacy and safety. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006. 97:126–137.

4. Portnoy J, Bagstad K, Kanarek H, Pacheco F, Hall B, Barnes C. Premedication reduces the incidence of systemic reactions during inhalant rush immunotherapy with mixtures of allergenic extracts. Ann Allergy. 1994. 73:409–418.

5. Hanifin JM, Cooper KD, Ho VC, Kang S, Krafchik BR, Margolis DJ, Schachner LA, Sidbury R, Whitmore SE, Sieck CK, Van Voorhees AS. Guidelines of care for atopic dermatitis, developed in accordance with the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD)/American Academy of Dermatology Association "Administrative Regulations for Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines". J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004. 50:391–404.

6. Platts-Mills TA, Mitchell EB, Rowntree S, Chapman MD, Wilkins SR. The role of dust mite allergens in atopic dermatitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1983. 8:233–247.

7. Tupker RA, De Monchy JG, Coenraads PJ, Homan A, van der Meer JB. Induction of atopic dermatitis by inhalation of house dust mite. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1996. 97:1064–1070.

8. Tan BB, Weald D, Strickland I, Friedmann PS. Double-blind controlled trial of effect of house dust-mite allergen avoidance on atopic dermatitis. Lancet. 1996. 347:15–18.

9. Novak N. Allergen specific immunotherapy for atopic dermatitis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007. 7:542–546.

10. Werfel T, Breuer K, Ruéff F, Przybilla B, Worm M, Grewe M, Ruzicka T, Brehler R, Wolf H, Schnitker J, Kapp A. Usefulness of specific immunotherapy in patients with atopic dermatitis and allergic sensitization to house dust mites: a multi-centre, randomized, dose-response study. Allergy. 2006. 61:202–205.

11. Cox L, Nelson H, Lockey R, Calabria C, Chacko T, Finegold I, Nelson M, Weber R, Bernstein DI, Blessing-Moore J, Khan DA, Lang DM, Nicklas RA, Oppenheimer J, Portnoy JM, Randolph C, Schuller DE, Spector SL, Tilles S, Wallace D. Allergen immunotherapy: a practice parameter third update. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011. 127:1 Suppl. S1–S55.

12. Hanifin JM, Rajka G. Diagnostic features of atopic eczema. Acta Derm Venereol (Stockh). 1980. 92:44–47.

13. Malling HJ, Weeke B. Immunotherapy: Position paper of the European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology. Allergy. 1993. 48:Suppl 14. 9–35.

14. Bateman ED, Hurd SS, Barnes PJ, Bousquet J, Drazen JM, FitzGerald M, Gibson P, Ohta K, O'Byrne P, Pedersen SE, Pizzichini E, Sullivan SD, Wenzel SE, Zar HJ. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention: GINA executive summary. Eur Respir J. 2008. 31:143–178.

15. Canonica GW, Baena-Cagnani CE, Bousquet J, Bousquet PJ, Lockey RF, Malling HJ, Passalacqua G, Potter P, Valovirta E. Recommendations for standardization of clinical trials with Allergen Specific Immunotherapy for respiratory allergy. A statement of a World Allergy Organization (WAO) taskforce. Allergy. 2007. 62:317–324.

16. Casanovas M, Martín R, Jiménez C, Caballero R, Fernández-Caldas E. Safety of immunotherapy with therapeutic vaccines containing depigmented and polymerized allergen extracts. Clin Exp Allergy. 2007. 37:434–440.

17. Ohashi Y, Nakai Y, Tanaka A, Kakinoki Y, Washio Y, Ohno Y, Yamada K, Nasako Y. Risk factors for adverse systemic reactions occurring during immunotherapy with standardized Dermatophagoides farinae extracts. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 1998. 538:113–117.

18. Ruëff F, Wolf H, Schnitker J, Ring J, Przybilla B. Specific immunotherapy in honeybee venom allergy: a comparative study using aqueous and aluminium hydroxide adsorbed preparations. Allergy. 2004. 59:589–595.

19. Müller UR. Venom immunotherapy: aqueous vs aluminium hydroxide adsorbed extracts. Allergy. 2004. 59:577–578.

20. Winther L, Arnved J, Malling HJ, Nolte H, Mosbech H. Side-effects of allergen-specific immunotherapy: a prospective multi-centre study. Clin Exp Allergy. 2006. 36:254–260.

21. Casale TB, Busse WW, Kline JN, Ballas ZK, Moss MH, Townley RG, Mokhtarani M, Seyfert-Margolis V, Asare A, Bateman K, Deniz Y. Immune Tolerance Network Group. Omalizumab pretreatment decreases acute reactions after rush immunotherapy for ragweed-induced seasonal allergic rhinitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006. 117:134–140.

22. Casanovas M, Martín R, Jiménez C, Caballero R, Fernández-Caldas E. Safety of an ultra-rush immunotherapy build-up schedule with therapeutic vaccines containing depigmented and polymerized allergen extracts. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2006. 139:153–158.

23. Akdis CA, Akdis M, Bieber T, Bindslev-Jensen C, Boguniewicz M, Eigenmann P, Hamid Q, Kapp A, Leung DY, Lipozencic J, Luger TA, Muraro A, Novak N, Platts-Mills TA, Rosenwasser L, Scheynius A, Simons FE, Spergel J, Turjanmaa K, Wahn U, Weidinger S, Werfel T, Zuberbier T. European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology/American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. Diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis in children and adults: European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology/American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology/PRACTALL Consensus Report. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006. 118:152–169.

24. Lower T, Henry J, Mandik L, Janosky J, Friday GA Jr. Compliance with allergen immunotherapy. Ann Allergy. 1993. 70:480–482.

25. Mueller RS, Bettenay SV. Evaluation of the safety of an abbreviated course of injections of allergen extracts (rush immunotherapy) for the treatment of dogs with atopic dermatitis. Am J Vet Res. 2001. 62:307–310.

26. Trimmer AM, Griffin CE, Boord MJ, Rosenkrantz WS. Rush allergen specific immunotherapy protocol in feline atopic dermatitis: a pilot study of four cats. Vet Dermatol. 2005. 16:324–329.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download