INTRODUCTION

The development of hepatic portal venous gas (HPVG) is rare but clinically important radiographic finding (1, 2). It has been reported to have an association with numerous abdominal conditions, including inflammatory bowel diseases, bowel obstruction, and bowel necrosis (2). Recently HPVG was also reported as a rare complication of endoscopic and radiologic procedures such as endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), liver transplantation, esophageal variceal band ligation and percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) (2-5). HPVG as a complication of endoscopic balloon dilatation has not been previously reported. Here we present a case of HPVG following endoscopic balloon dilatation in a patient with pyloric stricture.

CASE DESCRIPTION

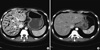

A 31-yr-old man was admitted with corrosive acids ingestion on July 13, 2010. Endoscopic findings showed long and deep linear ulceration and black pigmented mucosal change in the esophagus and stomach. Four weeks later the patient complained of abdominal distension and vomiting. Significant pyloric stricture was found in follow up endoscopy (Fig. 1A). The next day, we conducted endoscopic balloon dilatation, through an 8 mm balloon for 40 seconds. After endoscopic balloon dilatation, pyloric stricture was improved and endoscopy passage was possible. There was no evidence of perforation and only mild mucosal injury was observed (Fig. 1B). However, 1 hr after the balloon dilatation procedure, he complained of diffuse abdominal pain. His blood pressure was 95/65 mmHg, pulse rate was 110 times per min. The abdomen was soft and slightly distended with whole abdomen tenderness. However, no involuntary guarding or rebound tenderness was detected. Laboratory data showed white blood cell count of 8,930/µL, hemoglobin of 10.0 g/dL, C-reactive protein of 0.16 mg/dL, lactate dehydrogen level of 333 U/L. Abdominal CT showed large amounts of HPVG in the peripheries of the liver (Fig. 2A). The patient was moved to intensive care unit and an emergency operation was considered. However, we decided to go on conservative treatment because there was no clinical evidence of bowel necrosis or perforation and vital signs returned to normal range. The patient was monitored closely and received fluid replacement, Levin tube with natural drainage, broad-spectrum antibiotics. Five days later, we performed follow-up abdominal CT; hepatic portal gas showed complete spontaneous resolution (Fig. 2B). The patient was then transferred to the gastro-intestinal surgical team for elective surgery for gastrojejunostomy, and was discharged in good condition without any complication of hepatic portal venous gas.

DISCUSSION

In this report, we first described a case of HPVG following by endoscopic balloon dilatation. HPVG was first described by Wolfe and Evens in 1955 in infants with necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) (6). It has been reported in many abdominal conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease, diverticulitis, intraabdominal sepsis, pneumatosis intestinalis, pancreatitis, bowel obstruction and suppurative cholangitis (2, 7). It also has been reported as iatrogenic complications of as endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), liver transplantation, esophageal variceal band ligation and percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) (2-5). HPVG following endoscopic balloon dilatation has not been previously reported.

HPVG most often represents an ominous clinical finding. The clinical presentation of HPVG is usually consistent with acute abdomen but occasionally shows vague abdominal symptoms and nonspecific laboratory findings (1, 8). The major predisposing factor of the development of HPVG is the damage of intestinal mucosa combined with bowel dilatation or bacterial gas production (1, 8). Most authors agree that the formation of HPVG is a multiplex event in which two or three of these conditions are combined (1, 8). We speculated that the main cause of HPVG in our case was gastric dilatation. Increased intraluminal pressure forces intraluminal gas to pass through a damaged bowel wall, allowing the intraluminal gas to enter the portal circulation. Like this, the development of HPVG secondary to gastric dilatation has been reported in cases of ileus, barium enema and blunt abdominal trauma (9).

Originally the diagnosis of HPVG was based on plain abdominal radiography, primarily left lateral decubitus views (10). However, along with the development of CT scan, we found CT is more sensitive than plain film radiography. The pattern for HPVG in CT scan is described as a tubular lucency branching from the porta hepatis to the liver capsule (10, 11). The gas travels peripherally in the portal vein consequent to the centrifugal flow of blood, and the branching pattern with a peripheral distribution extending to within 2 cm of the liver capsule (10, 11). Additionally, in abdomen CT finding, HPVG must be differentiated from gas in the biliary tracts such as pneumobilia, which tends to move with the centripetal flow of bile toward the hilum, and whose central air lucencies do not extend to within 2 cm of the liver capsule (10).

Gas in the portal venous system was once regarded as a fatal event (12). However, in most clinical settings, the finding of HPVG alone cannot be a predictor of mortality or an indication for emergency exploration. The key point when making a decision of its surgical management is the presence of peritonitis or bowel perforation (13, 14). In our case, there was no clinical evidence of peritonitis or bowel perforation. Therefore, we decided to go on conservative treatment. In addition, if there is a gastric dilatation due to endoscopy, inserting of a Levin tube for gastric decompression plays an essential role in rapid removal of portal vein gas (9).

In conclusion, we report the first case of HPVG followed by endoscopic balloon dilatation. Gas in the portal vein in our case may occur as a transient incidental finding with gastric dilatation and mucosal damage. HPVG resulting from iatrogenic causes, the amount of portal vein gas may be not an indication of surgical management and medically stable patients without sign of bowel peritonitis or perforation could be effectively managed with supportive care.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download