Abstract

Patients' insight has a critical role in the recovery from problematic behavior. The aim of this study was to evaluate the effects of a brief intervention to promote insight among alcohol-dependent patients. A total of 41 alcohol-dependent patients (30 males, 11 females) in an insight-deficient state who had been admitted to a community-based alcohol treatment center, were randomized into two groups based on their admission order: an intervention group (IG) (n = 20) and a control group (CG) (n = 21). Patients in both the IG and CG participated in an identical treatment program with one exception: patients in the IG were required to undergo five sessions of brief individual intervention focusing on insight enhancement. Changes in insight state were assessed after the intervention. The IG exhibited significant (P < 0.05) changes in the distribution of insight level, while the CG did not exhibit any significant changes in the distribution of insight level. The insight score after intervention was significantly (P < 0.05) greater for the IG than the CG with adjustment for the baseline characteristics. The results suggest that a brief individual intervention focused on insight enhancement may be an effective tool to improve insight among alcohol-dependent patients.

Generally, insight is considered to be the conscious awareness and understanding of one's own symptoms of maladaptive behavior. True insight can be defined as an understanding of the objective reality of a situation coupled with the motivation and emotional impetus to master the situation or change one's own behavior (1).

For the role of insight, researchers have focused on how insight affects patients. It has been found that a lack of insight is associated with poorer psychosocial functioning among patients with mental disorders (2) and with higher rates of false negatives in screening tests among patients with alcohol dependence (3). It was also reported that bipolar patients' insight into treatment is an independent predictor of adverse clinical outcomes (4). A study of alcohol-dependent patients suggested a close relationship between the state of patients' insight and their level of motivation to change their own behavior (5). In addition, the rate of one-year abstinence among alcohol-dependent patients after discharge from a hospital appears to be significantly affected by their level of insight (6). These results suggest that insight has a positive effect on the diagnostic process, motivation for treatment, and alcohol-related behavioral change, and may play a critical role in the recovery process.

Studies have reported that 77.6%-94.7% of Korean alcohol-dependent patients who maintain contact with the treatment system lack insight (7, 8). Another study has also reported that 72.6% of indigenous southern Taiwanese diagnosed with alcoholism have poor insight into their own alcohol-related problems (9). Taken together, these findings suggest that physicians should try to improve alcohol-dependent patients' level of insight.

Improving insight among patients with alcohol dependence may be an important modifiable therapeutic target to help them improve outcomes. While trying to motivate subjects to change their drinking behavior, it is important to help them perceive the discrepancy between their present behavior and their personal goals. Findings that a patient's insight can be enhanced through a variety of group treatment programs have indicated that insight is a factor that can be changed through therapeutic efforts (10, 11). However, up to now, few studies have focused on how individual intervention or educational counseling can help patients with alcoholism improve their level of insight.

This study was designed to evaluate the effectiveness of an experimental individual brief intervention on the promotion of insight in insight-deficient alcohol-dependent patients. The hypothesis was that alcohol-dependent patients who participated in the individual intervention sessions would exhibit improved levels of insight, as compared to those who did not participate.

Patients who had been hospitalized at a 400-bed community alcohol treatment center from March to May 2008 in Daejeon, Korea, were invited to participate in an interview for baseline data collection, including an assessment of their level of insight. All patients met the DSM-IV-TR (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition, text revision) criteria for alcohol dependence (12). We excluded any patients who were undergoing detoxification treatment or had cognitive deficits. Insight level was rated as 'poor', 'fair' or 'good' based on the Hanil Alcohol Insight Scale (HAIS) (13). Among the 68 patients who had been admitted consecutively during the research period, a total of 41 patients whose insight level was rated as 'poor' or 'fair' were included as subjects. Subjects were allocated into one of two groups through one-to-one randomization by admission order: an intervention group (IG) (n = 20) and a control group (CG) (n = 21). Basically, both IG and CG participated in an identical treatment program: they participated equally in all usual ward activities such as drawing, arts and crafts, calligraphy, singing, and group meetings including Alcoholics Anonymous. The only exception was that patients in the IG were also required to attend five individual sessions of brief intervention focusing on insight enhancement. There was no patient who did not complete the intervention.

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of the Hanmaum Alcohol Treatment Center (IRB No. 0802-01) and informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Baseline data collection was carried out by a physician, who gathered sociodemographic and drinking-related characteristics for each patient as well as his or her level of insight. Insight score was measured using the HAIS (13). Sociodemographic characteristics included age, sex, occupation, religion, academic career, family function based on Family APGAR score (14), and cohabitation with spouse. Drinking-related characteristics included drinking frequency per week, drinks per drinking day, total number of hospital admissions due to drinking, and severity of alcohol problems based on Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) score (15). Level of insight state was assessed again after completion of the intervention by a different physician who had not been involved in the process of randomizing the subjects or the intervention. Changes in insight scores and distributions of insight levels were then assessed.

The intervention was conducted individually. Each patient in the IG participated in five sessions over the course of two weeks; these focused on insight enhancement and were led by a psychiatrist who managed alcohol treatment programs. Each session included structured themes and was designed to be completed within 15 min. For the treatment adherence to the manual and treatment fidelity, therapist had been educated about the intervention through several times of seminars before this study and each session was conducted in semi-structured counseling format according to the manual proposed by Kim et al. (16).

Theoretically, motivation to change occurs when an individual perceives a discrepancy between where they are and where they want to be. The motivational enhancement approach to alcoholism seeks to improve and focus the patient's attention on such discrepancies with regard to his or her drinking behavior (17). Providing feedback about problems associated with drinking and related symptoms, as one of the motivational elements, also has been recommended to motivational enhancement therapists (18). The brief individual intervention in this study included three sessions (problem-oriented; control/dependence-oriented; and surrounding-oriented session) focused on making the patient aware of his or her reality and two sessions (treatment-oriented; and abstinence-oriented session) on behavioral changes. After the patient expressed his or her opinions and/or feelings about the themes in each session, the doctor provided a supportive and educational intervention from a medical perspective.

The structured themes for each session were as follows: drinking habits and problems with regard to the physical, psychiatric, and social aspects of the patient in a problem-oriented session; loss of control over drinking, alcohol craving, and withdrawal symptoms in a control/dependence-oriented session; family suffering, complaints about surroundings, and role or meaning of their existence in the community in a surroundings-oriented session; the necessity of treatment or behavioral change, need for help from medical staff, colleagues, family, and self-help groups in a treatment-oriented session; and goals for change, feasibility of the goal, and differences between abstinence and controlled drinking in an abstinence-oriented session.

The problem-oriented session was focused on helping patients to realize problems induced by drinking. The control/dependence-oriented session was focused on the biological symptoms of alcohol dependence to help patients get a better understanding of alcohol dependence as a disease. In this session, patients were educated that alcohol dependence is not a moral issue, but that it is, rather, a medical disorder requiring treatment. The surroundings-oriented session emphasized exploration of the meaning of self within the context of the patient's surroundings, including family and community. Patients were encouraged to perceive the hidden love or affection within their community that was available to help heal their damaged emotional connections with the world. The treatment-oriented session was focused on improving the patient's motivation for treatment and guiding him or her to step into the therapeutic milieu. The abstinence-oriented session was focused on setting goals for behavioral change.

The HAIS is a 20-item questionnaire used to measure insight among alcohol-dependent patients. It has a sensitivity of 76.9%-100.0%, and, specificity, 83.3%-94.9% for the insight assessment by psychiatrists' interviews with a patient (13). On the basis of total score, individuals who score from -20 to 3 are classified as having poor insight, scores from 4-15 indicate a fair level of insight, and scores from 16-20 indicate a good level of insight. The HAIS has five subsections as follows. Problems-oriented insight (POI) refers to the level of recognition that one has problems with regard to drinking; this is classified as a self-oriented reality. Control/dependence-oriented insight (C/DOI) refers to the degree of recognition of one's state being out of control and dependent on alcohol; this is also classified as a self-oriented reality. Surroundings-oriented insight (SOI) refers to the level of recognition that one's drinking puts family members and others nearby in pain and under stress; this is classified as an others-oriented reality. Hospitalization/treatment-oriented insight (H/TOI) refers to the level of acceptance of the necessity of treatment and one's attitude towards treatment; it is classified as a motivation category. Abstinence-oriented insight (AOI) refers to the level of understanding the necessity of abstinence and planning for it; it is classified as a goal category.

The AUDIT is composed of 10 questions about alcohol consumption, drinking behaviors, and alcohol-related problems. The sensitivity of AUDIT for hazardous or harmful drinking is 92%, and its specificity is 94% (15).

The Family APGAR is a valid and convenient diagnostic tool to assess the level of function in the patient's family (14). This questionnaire can be completed by a patient in less than 10 min and yields information that assesses family function in terms of five components: adaptability, partnership, growth, affection, and resolution. Total scores ranging from 0-3 indicate a severely dysfunctional family, scores from 4-6 indicate a moderately dysfunctional family, and scores from 7-10 indicate a highly functional family.

SPSS 13.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for all statistical analyses. Baseline characteristics were compared between the IG and the CG using the t-test, chi-squared test, and Fisher's exact test. The exact McNemar test was used to assess changes in distribution in insight levels. The Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to evaluate improvement in insight scores. To compare the insight scores of IG before and after intervention with those of CG, insight scores were log-transformed to normalize distributions for analysis. ANCOVA was performed for the log-transformed value of insight score of IG and CG with adjustment for the differences in baseline characteristics. A P value of 0.05 was used to indicate significance for all statistical tests.

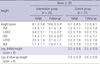

Table 1 lists the characteristics of the subjects. Subjects had a mean (± SD) age of 48.0 (7.6) yr and 75.3% were male. Overall, 75.6% were employed. Only 34.2% of subjects were currently cohabitating with a spouse. As for the family function, the mean (± SD) family function (APGAR) score was 5.4 (2.1) in the IG and 5.0 (2.0) in the CG which indicated a moderately dysfunctional family environment for the both IG and CG.

Generally, the IG and CG shared similar socio-demographic characteristics with regard to age, sex distribution, occupational state, religion, academic career, family function score, and cohabitation with spouse. The groups also did not differ significantly in drinking-related characteristics that indicate the severity of alcohol problems, including alcohol consumption, the number of hospital admissions due to alcohol, and AUDIT scores. The CG initially scored slightly higher on level of insight, but the difference was not statistically significant.

A total of 100 of sessions of individual intervention were completed for the 20 subjects in the IG. The mean (± SD) time for each session was 13.7 (3.5) min.

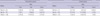

With regard to the distribution of subjects by insight level, the IG changed significantly (P < 0.05, chi-squared = 7.141) from 9 (45.0%), scoring as having 'poor' insight, and 11 (55.0%), as having 'fair' insight before intervention, to 3 (15.0%), scoring as 'poor', 14 (70.0%), as 'fair', and 3 (15.0%), as 'good', after intervention. The CG changed from 7 (33.3%), initially scoring as 'poor', and 14 (66.7%), as 'fair', to 7 (33.3%), as 'poor', 13 (61.9%), as 'fair', and 1 (4.8%), as 'good', over the same period, but these changes were not statistically significant (Table 2).

The initial insight score ranged from -6 to 15 in the IG and -7 to 17 in the CG. Follow-up insight score ranged from 2 to 20 in the IG and -6 to 16 in the CG. The mean (± SD) insight score for the IG increased significantly (P < 0.01, Z = -3.433) from 6.1 (5.8) before the intervention to 10.8 (5.4) after the intervention. The mean (± SD) insight score for the CG increased from 6.7 (6.5) to 7.3 (6.1) after the same time period, but this increase was not statistically significant. Of the five domains of insight, the IG improved significantly in POI (P < 0.01), C/DOI (P < 0.01), and SOI (P < 0.05). The log-transformed value of (insight score + 8) after intervention was significantly (P < 0.05, F = 5.298) greater for the IG than the CG by ANCOVA with adjustment for the baseline characteristics such as age, sex, occupation, religion, education, family function score, cohabitation with spouse, drinking frequency, drinks per drinking day, number of admissions due to drinking, AUDIT score, and initial insight score (Table 3).

This study evaluated the effectiveness of an experimental individual brief intervention on the promotion of insight among insight-deficient alcohol-dependent patients. This is the first study to attempt a brief individual intervention to enhance the insight of alcohol-dependent patients. The results are important because they indicate that a brief program of five individual intervention sessions may improve insight among alcohol-dependent patients. It is remarkable that each treatment session was, on average, only 13.7 min, comparing that typical therapy requires more long time sessions.

Individual interventions were conducted based on the hypothesis that alcohol-dependent patients who participated in a brief intervention program would have better insight scores than others who had not, and that their insight scores would increase after participation. Before the intervention, the IG and CG did not differ significantly in insight scores, even in the general characteristics, including the severity of alcohol problems. Our finding that the IG scored much higher for insight after the intervention, as compared with the CG, accepts our hypothesis.

The results indicate that a brief individual intervention increased overall insight scores from 6.1 to 10.8. These findings correspond well with previous report that mean insight scores of alcohol-dependent patients were increased from 6.4 to 9.1 through intensive group education over two months (19). Insight-oriented interventions are based on the assumption that 'good' insight can be interpreted as true insight, which is the overall goal. Therefore, increasing the number of patients who score as having 'good' insight could be important. Our results indicate an increase of 15.0% after intervention, similar to the results of a group program conducted over five weeks, which yielded an increase of 15.4% (11). Therefore, our brief intervention appears to yield similar results to the intensive group education program. However, our results were not as good as those reported by another study (10), which obtained a 36.3% increase when the intervention incorporated social and cultural factors relating to the patients. Im et al. (10) implemented a cognitive behavioral intervention, which constituted a sort of a group program based on a Korean traditional moral concept. Taken together, these results indicate that a therapeutic intervention that reflects social and cultural factors relating to the patients could be more effective in promoting insight among alcohol-dependent patients.

Improving a patient's objective reality relating to his or her disease could be the first step toward his or her new self-identity. Brown (20) referred to this as the transition point at which an alcohol-dependent patient is in transition to recovery. The patient's reality may also be similar to the concept of 'discrepancy' used in motivational enhancement therapy (21); this is developed through an awareness of the adverse personal consequences of his or her drinking and can precipitate a crisis of motivation for change. Our results revealed that among the domains of insight, changes were particularly significant in POI, C/DOI, and SOI scores. These results may indicate that the brief individual intervention sessions focused on insight were most effective in the 'reality' category. Therefore, it could be interpreted that our brief intervention may have a role in helping patients in the 'precontemplation' stage set out in Prochaska and DiClemente's model (22, 23). However, our findings revealed little improvement in AOI and H/TOI scores. Although the intervention appears to promote insight among alcohol-dependent patients, AOI and H/TOI would be the one that would be most predictive of good therapeutic outcomes, the details of the intervention need to be modified to motivate patients and help them to set the goal of abstinence.

The findings of our experimental research are limited in their ability to be generalized. Our subjects only included patients who had been admitted to a single hospital. In addition, although baseline characteristics did not appear to differ significantly between the IG and the CG, the total number of subjects was pretty small to control for differences in baseline insight scores. A larger number of subjects would be needed to generalize our hypothesis. Also, it is important to clarify whether there is any relationship between insight enhancement and clinical outcome improvement. However, from out results, it cannot be said clearly these association because this study is not long-term prospective study but a short experimental study. It needs further studies about whether the improvement of insight can predict the better clinical outcomes of alcohol consumption.

However, our findings suggest that insight is a factor that can be changed by brief individual programs. Mistaken belief that drinking is a traditional token of friendship and a man who drinks more is more masculine and "brotherly", is entrenched among Korean people as in other Confucian culture. Because insight-deficient alcohol-dependent patients are common in clinical settings in Asian countries, while it is not well known in the West, further studies are needed to find a variety of insight enhancement interventions applicable to the clinical field.

In conclusion, the results of this study suggest that a brief individual intervention focused on insight enhancement may be an effective tool to improve insight among alcohol-dependent patients.

Figures and Tables

Table 3

Changes in insight score of the subjects

*P < 0.05; †P < 0.01 by Wilcoxon singed ranks test; ‡P < 0.05 by ANCOVA adjusted for age, sex, occupation, religion, education, family function score, cohabitation with spouse, drinking frequency per week, drinks per drinking day, the number of admission due to drinking, AUDIT score, and initial insight score. POI, problem-oriented insight; C/DOI, control/dependence-oriented insight; SOI, surroundings-oriented insight; H/TOI, hospitalization/treatment-oriented insight; and AOI, abstinence-oriented insight.

AUTHOR SUMMARY

Brief Insight-enhancement Intervention among Patients with Alcohol Dependence

Jin-Gyu Jung, Jong-Sung Kim, Gap-Jung Kim, Mi-Kyeong Oh, and Sung-Soo Kim

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effects of a brief intervention to promote insight among alcohol-dependent patients. Forty one alcohol-dependent patients in an insight-deficient state who had been admitted to an alcohol treatment center, were randomized into two groups based on their admission order: an intervention group (IG) (n = 20) and a control group (CG) (n = 21). Patients in both the IG and CG participated in an identical treatment program with one exception: patients in the IG participated in the five sessions of brief individual intervention focusing on insight enhancement. Changes in insight state were assessed after the intervention. The IG exhibited significant changes in the distribution of insight level and significant improvement in insight score, while the CG did not. The results suggest that a brief intervention focused on insight enhancement may be an effective tool to improve insight among alcohol-dependent patients.

References

1. Sadock BJ. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, editors. Signs and symptoms in psychiatry. Kaplan and Sadock's Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. 2005. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;847–859.

2. Amador XF, Flaum M, Andreasen NC, Strauss DH, Yale SA, Clark SC, Gorman JM. Awareness of illness in schizophrenia and schizoaffective and mood disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994. 51:826–836.

3. Cho KC, Kim JS, Jung JG, Kim SS, Lee JG, Choi DH. Effects of insight level on the sensitivity of alcoholism screening tests in alcohol dependent patients. Korean J Fam Med. 2010. 31:523–528.

4. Yen CF, Chen CS, Yen JY, Ko CH. The predictive effect of insight on adverse clinical outcomes in bipolar I disorder: a two-year prospective study. J Affect Disord. 2008. 108:121–127.

5. Kim KM, Kim JS, Kim GJ, Jung JG, Kim SS, Kim SM, Pack HJ, Lee DH. The readiness to change and insight in alcohol dependent patients. J Korean Med Sci. 2007. 22:453–458.

6. Kim JS, Park BK, Kim GJ, Kim SS, Jung JG, Oh MK, Oh JK. The role of alcoholics' insight in abstinence from alcohol in male Korean alcohol dependents. J Korean Med Sci. 2007. 22:132–137.

7. Kim SS, Shin JJ, Whang IB, Chai SH. Relationship between insight level and psychological characteristics in alcoholic patients. J Korean Acad Addict Psychiatry. 2002. 6:49–57.

8. Kim KC, Lee KS, Jung G, Shin SE. The relationship between insight level and defense mechanisms in alcoholic patients. J Korean Acad Addict Psychiatry. 2004. 8:115–123.

9. Yen CF, Hsiao RC, Ries R, Liu SC, Huang CF, Chang YP, Yu ML. Insight into alcohol-related problems and its associations with severity of alcohol consumption, mental health status, race, and level of acculturation in southern Taiwanese indigenous people with alcoholism. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2008. 34:553–561.

10. Im SB, Yoo EH, Kim JS, Kim GJ. Adapting a cognitive behavioral program in treating alcohol dependence in South Korea. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2007. 43:183–192.

11. Kim JS, Park BK, Yu IS, Oh MK. Improvement of insight in patients with alcohol dependence by treatment programs. J Korean Acad Fam Med. 2000. 21:1180–1187.

12. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 2000. 4th ed. Washington DC: APA;text revision.

13. Kim JS, Kim GJ, Lee JM, Lee CS, Oh JK. HAIS (Hanil Alcohol Insight Scale): validation of an insight-evaluation instrument for practical use in alcoholism. J Stud Alcohol. 1998. 59:52–55.

14. Smilkstein G. The family APGAR: a proposal for a family function test and its use by physicians. J Fam Pract. 1978. 6:1231–1239.

15. Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT); WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption II. Addiction. 1993. 88:791–804.

16. Kim JS, Park BK, Kim GJ. Diagnosis and treatment of alcohol-related disorders. 2001. Seoul: Hankuk Medical Publishing Co.

17. Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing. 1991. New York: Guilford Press.

18. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. NIH Publication No. 94-3723. Motivational enhancement therapy manual: a clinical research guide for therapists treating individuals with alcohol abuse and dependence. 1999.

19. Sung SK, Lee JJ, Kim HO, Lee KH. Effectiveness of inpatient treatment program on the insight and satisfaction of alcoholics. J Korean Acad Addict Psychiatry. 2002. 6:20–29.

20. Brown S. Treating the alcoholic: a developmental model of recovery. 1985. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

21. Miller WR. Motivational enhancement therapy with drug abuser. 1995. National Institute on Drug Abuse. R01-DA08896.

22. Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. The transtheoretical approach: crossing traditional boundaries of therapy. 1984. Homewood II: Dow Jonese Irwin.

23. Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Miller W, Healther N, editors. Toward a comprehensive model of change. Treating Addictive Behaviors: Processes of Change. 1986. 1st ed. New York: Plenum Press;4–27.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download